Women’s underpants really didn’t make a name for itself until suffragette Amelia Bloomer created her famous “bloomers” in the 1850s, modeled after the traditional loose trousers worn by women in Turkey. It became a craze, a punk rebellion against the strict, stiff undergarments of the Victorian Age. Bloomer was also the first woman to own, operate and edit a newspaper for women. Cut to the 21st century, Emily Labowe is carrying the torch of Bloomer’s rebellion with a new line of French cut, cotton intimates with delicately embroidered flowers, cacti, and fauna. Made locally, Poppy Undies is a celebration of femininity and mindfulness. As part of the launch, Labowe has also launched a quarterly newspaper. The first issue has contributions from a global coterie of artists and friends, like Langley Fox and Devendra Banhart. In the following conversation, Labowe and Banhart discuss underwear, lockdown, and life in our skivvies.

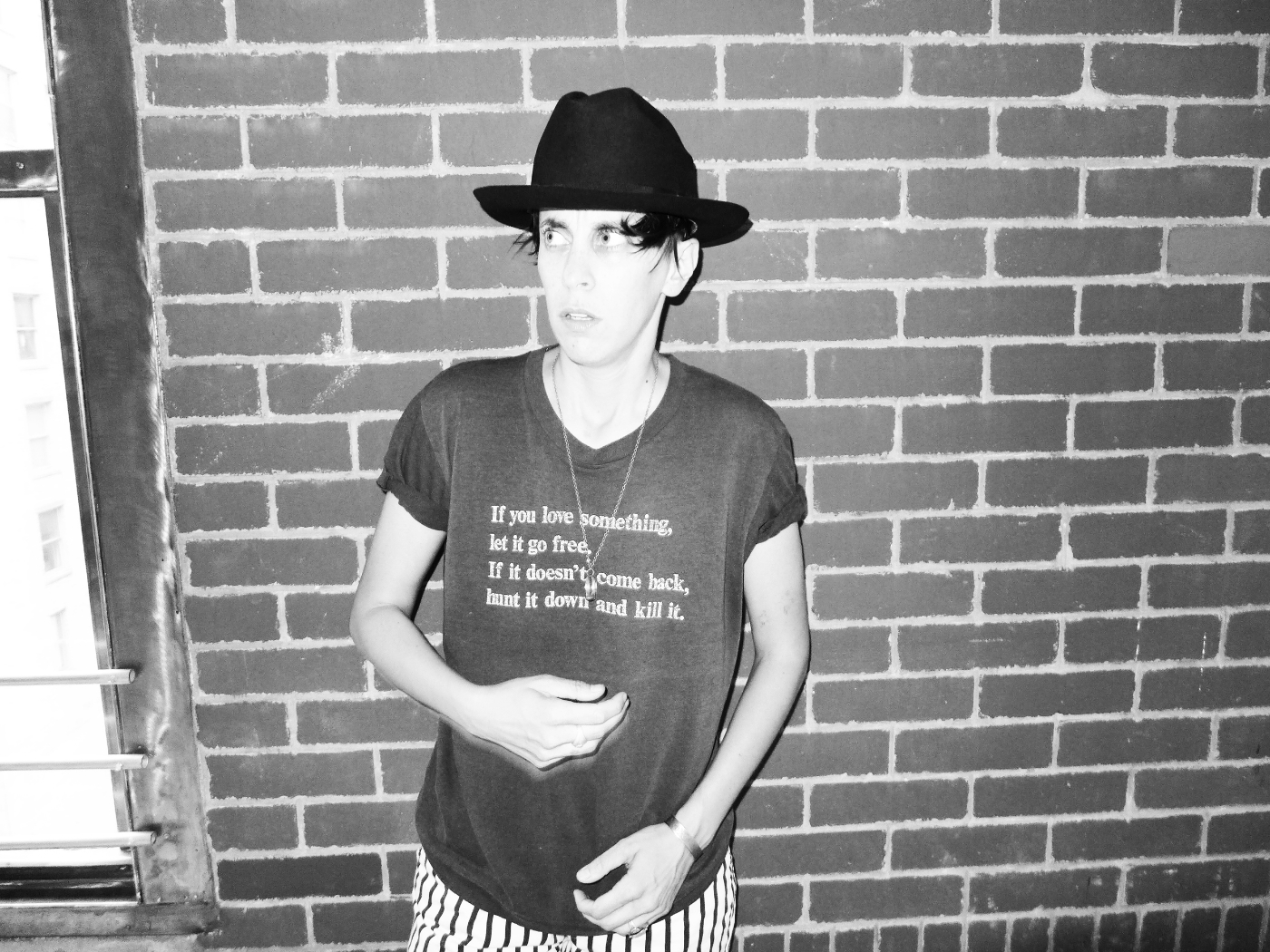

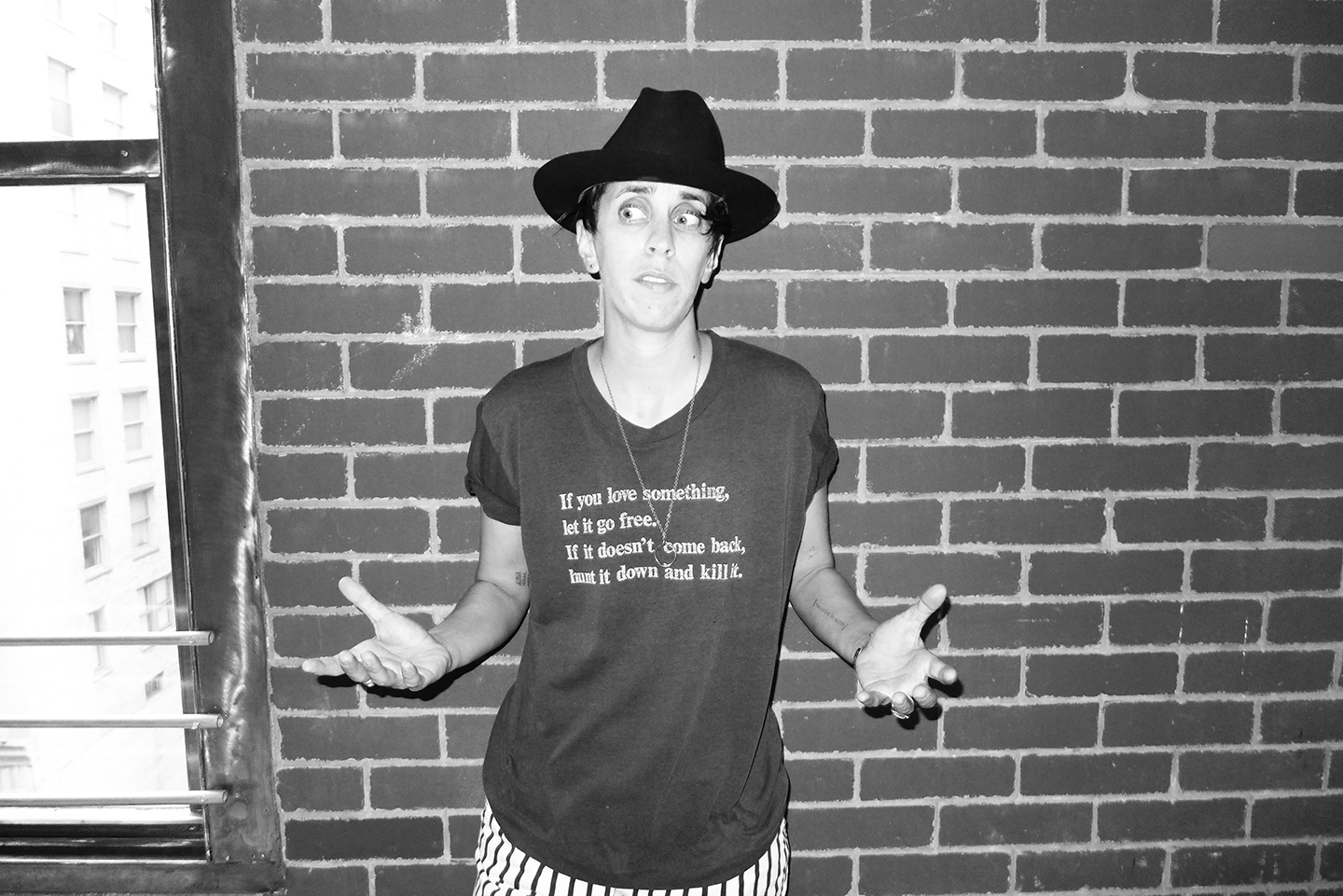

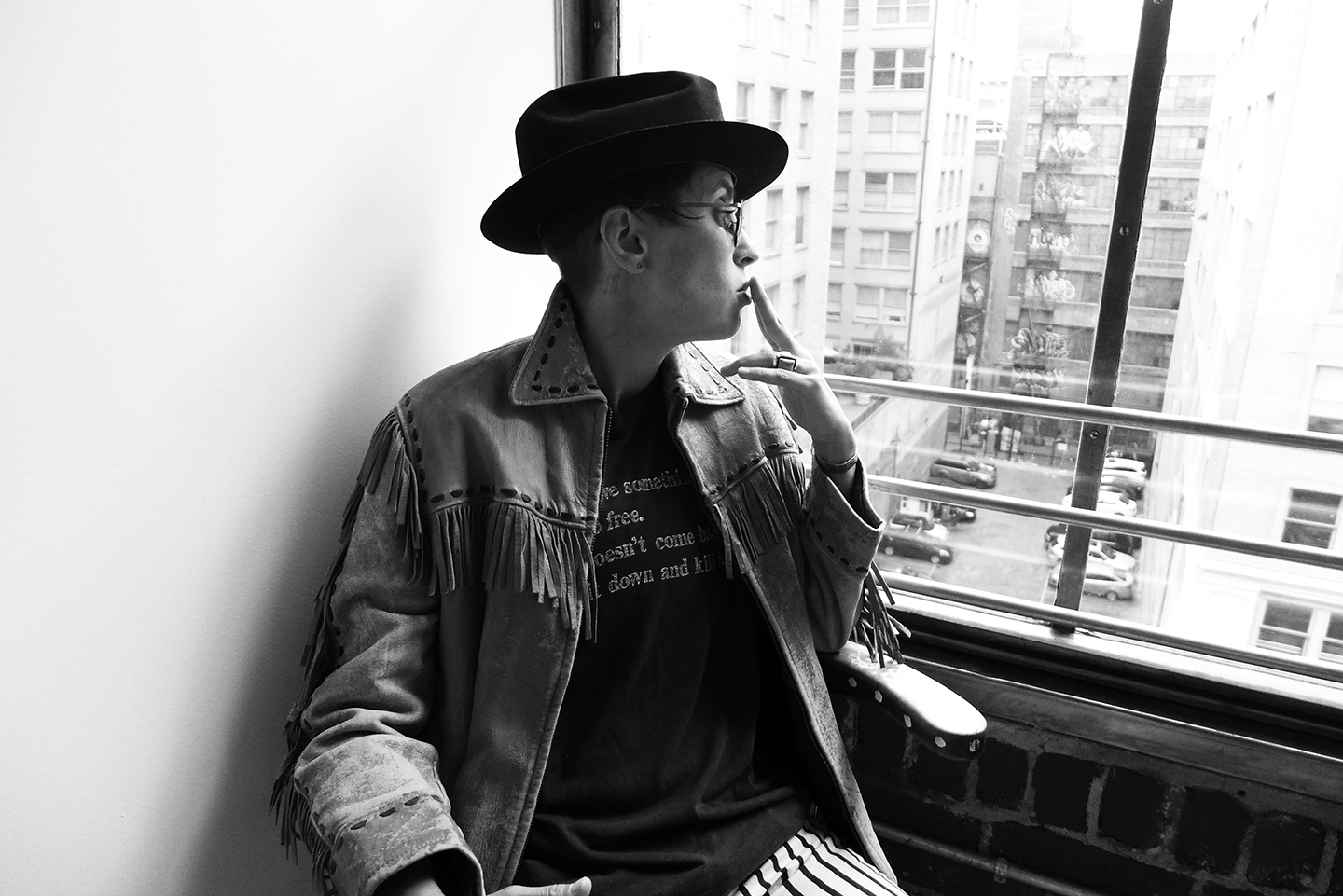

DEVENDRA BANHART I’m interviewing the wonderful, lovely, talented, amazing, incredible in every way, billion-threat, Emily Labowe, the CEO and founder and creative director of Poppy Undies, that launched two days ago. We do know each other, but I don’t know the answers to these questions. If Poppy Undies were a film, what would it be?

EMILY LABOWE Labowe That’s a really good question. I put together a thing called “brief scenes”—ha ha, so funny—of my favorite movies that have really great underwear scenes in them. I would probably say Bridget Jones’s Diary, or Empire Records’s underwear scene is pretty amazing, when Liv Tyler takes off her skirt in her boss’s office. Pretty wonderful.

BANHART Where do you think your entrepreneurial and handmade goods making origins come from?

LABOWE I think my mom. She taught me how to embroider four years ago, during Passover, on a matzo cover, and it was so fun. As a kid too, I was always knitting or crocheting with her, or crafting. I don’t know about the entrepreneurial part, but I was selling cookies and Pocky in high school, because that was the cool thing to do. People would bring Costco desserts and sell them in duffle bags because it was public school; we didn’t have fun food. And I was like, I want to make friends, so I baked stuff and sold it, and I made a couple friends.

BANHART And you made a couple bucks!

LABOWE And friends, more importantly.

BANHART Okay, so friends are more important than bucks. How was Poppy Undies born?

LABOWE There a fair amount of niche brands that embroider jean jackets, or shirts, and I felt that intimates was a really interesting item of clothing to have embroidery on because you either wear underwear that makes you feel sexy, or you wear it for someone else, and you have a little special secret thing on your underwear.

BANHART Totally. There’s a very obvious hierarchy in clothing lines, and I think intimates are really undervalued and underappreciated in that hierarchy. It’s the most personal item of clothing you can wear, and in the same way that architecture affects the way you think—you know, you’re in a particular room, you design it a particular way, it really does affect the way you think. I think the actual cut of something that is touching you in the most intimate place, and the feel of it, the look of it, does affect how you actually feel.

LABOWE Totally, and confidence and comfort is so important.

BANHART Why a poppy, and how did you settle on that name?

LABOWE Two different thoughts. It’s very classic: California–poppy flowers. I love poppies, and the name Poppy is important to me because it’s what I used to call my grandpa.

BANHART I love that. Very, very sweet. Let’s talk about the art newspaper that’s also part of the launch; it’s also going to be an ongoing part of Poppy. The theme of it, in terms of the short stories, the poems, the models shown alone, the negative space in the layout, seems to be one of isolation and remoteness, yet the entire mission statement of Poppy is about self-love and celebrating femininity—something that seems harder to do and more important than ever to strive for in this time of confinement. Can you speak on that?

LABOWE I think retrospectively, the experience of quarantine really influenced the line and the paper just in terms of—personally for me, I feel like I aged like five years during this time in good ways, and bad ways too. I just changed a lot, and feel a newfound sense of confidence and self-esteem, and that is really what the backbone of the line is, is promoting self-love and acceptance. In terms of you getting a sense of isolation, that’s not entirely purposeful. I wanted to create a sense of community with the line, so that’s why putting a bunch of friends together and collaborating on something adds to the whole world of the brand.

BANHART And I guess that is how we all feel, kind of alone together. Everyone has their own page, and the spacing is done in a way that everybody’s piece is honored and it’s not cluttered in any way, but we’re all part of the same newspaper.

LABOWE Exactly, yeah.

BANHART You worked with all of your friends. Could you talk about some of them?

LABOWE You have a drawing on page fifteen, and on the same page my friend Javier Ramos, who’s a chef in LA, wrote a recipe for the paper, and then my friend Jeff who laid out the paper, printed these recipe cards, it’s kind of like a postcard, but the back is a handwritten recipe. Ali Mitton did all the photography, which is from the campaign, and then I have a couple friends’ essays in there, and my friend Renee Parkhurst who’s an artist, sent me some paintings, and Langley Fox sent me a drawing. There’s a bunch of cool stuff in there.

BANHART There’s also like a little definition of a few words.

LABOWE Oh yeah, on the gutter of each page are poems from our friend Emily Knecht who wrote vocabulary words that play into the theme of heartbreak and love, and the experience of COVID.

BANHART I guess the other thing is soon—I’ll be doing twenty drawn-on versions.

LABOWE Devendra is going to do a couple limited edition drawings directly on some of the pages, and that will be on the website soon.

BANHART You know that I am a practicing Buddhist, in the Vajrayana tradition, but in Zen, which is very dear to me, there’s a tradition called koans. A koan is a question that a teacher will ask a disciple and they will mull it over for quite some time. There’s actually an answer to them, and it’s kind of a test.

LABOWE But you’re not supposed to answer right away?

BANHART I guess some people probably do and maybe get it right.

LABOWE So there’s a correct answer?

BANHART Yeah, there is actually a correct answer, but traditionally people will mull it over some time. So, I’m putting you in the real hot seat here and asking you to answer koans.

LABOWE Are you going to make a (imitates buzzer noise) if I’m wrong?

BANHART I’m going to electrocute you. Here’s the first onLabowe what is your original face before you were born?

LABOWE You.

BANHART The letter, or y-o-u?

LABOWE Y-o-u.

BANHART Nice. When you can do nothing, what can you do?

LABOWE Everything.

BANHART What is the color of wind?

LABOWE Light.

BANHART Do you think that when we have a child, it will inspire you to make Poppy for kids?

LABOWE Yeah, they’re not on the website yet, but I have onesies that I’ve embroidered. I’ve been giving them just to friends right now, but I definitely want to do that on a bigger scale. I’ve just kind of been testing it out with friends who have new babies.

BANHART As far as I know, there are some new items in the works, like mesh underwear?

LABOWE Yeah. I actually sold out of everything already, so the next drop will be the beginning of January, and there will be unisex boxers and mesh underwear as well.

BANHART And will the designs be different?

LABOWE Yes. I’ll restock what I have; that will stay the same, like the essential stuff, but the new pieces will have new designs.

OLIVER KUPPER I guess I’ll jump in with a few questions. How has it been living and working during the pandemic?

LABOWE I live alone, and quarantine was a very weird time because in the beginning, I wasn’t even seeing my family. It was intensely lonely, going through a hard emotional time as well, which I think influenced a lot of the paper, but I have a newfound sense of strength. And I was able to pour myself into this, which was great, so I stayed busy. Pretty much on my own, though.

BANHART I would say it’s almost like we’re just arriving at a time of adapting to the reality of how long this is all going to last.

LABOWE Especially now that we’re back in lockdown.

BANHART Back in lockdown, and it’s such a huge shift that none of us have ever experienced in our entire existence. It’s taken all this time, for me at least, to feel like I really have to get used to this. I’m not going to be touring. I’m not going to be doing the things I used to do. We’re going to be socializing. There is this extra tremendous wave of collective mourning that is such a part of everyday life now. Mourning is so huge for the amount of people that are dying every day, and then all those people’s families that are mourning—they’re losing their loved ones every day, and obviously how different the lives are of first responders from us, which we’re kind of having to deal with ourselves in a new way, where many first responders have not had that opportunity. They are dealing with this pandemic every moment. And I’ve lost friends to this pandemic. It’s really, really strange because even mourning the loss of my friend Hal Willner feels like it’s on hiatus. I couldn’t go to a funeral. I can’t talk or traditionally mourn. It’s important to remember that whatever I’m going through is certainly being magnified by this tremendous collective mourning and suffering. It’s important to try and look at it as an opportunity for growth.

KUPPER It’s interesting. Also, a lot of us are not wearing any clothes, either.

LABOWE Right, totally. I’ve been wearing boxers and underwear. It’s that or sweatpants now that it’s a bit colder, but I feel like it’s quite relevant. The loungewear business is booming, which is cool.

BANHART I’m just in my corduroy thong, as usual.

KUPPER Any plans for edible Poppies?

LABOWE Wow. You just sparked a really great idea. Shit. I wish I could’ve done that in time for Valentine’s Day. But hey, maybe I will. What do you make it out of? There are those candies that are on strings, but also I’m imagining—remember Fruit by the Foot? If you make that for Valentine’s Day, vould you eat it off of yourself if you don’t have a partner? I’ll let you know. I’ll try it.

KUPPER My last question—do you have any tips for feeling sane during this time.

LABOWE That’s a good, good question. For me, I had a somewhat sense of it before because my usual job is so random, and I don’t have a schedule. It’s like having a routine to get you through the week, so you have your coffee, and then you go for your walk, which I should do more often. Having a routine is the number one way for me to feel sane, I think. And going to the beach, which I haven’t done in a while, and I love going to the beach when it’s cold, but I was doing that very, very frequently from March until it got a bit chilly.

BANHART My advice is to hold space for your sadness. Hold space for your sorrow, and expand your support system.

LABOWE For sure. Even if it’s just a phone call or Zoom with a friend. You’ll feel so much better after.

Click here to explore Poppy Undies. Purchase a limited edition of Poppy Paper with original drawings by Devendra Banhart.