text by Tara Anne Dalbow

If art historian Simon Schama’s assertion is correct that “landscapes are culture before they’re nature” and “scenery is built up as much from strata of memory as from layers of rock,” then when Teresa Baker, a member of the Mandan and Hidatsa tribes, surveys the Northern Plains she sees far more than meets the eye. The nine technicolor tapestries included in From Joy to Joy to Joy offer a glimpse beneath the visible surface of her ancestral homeland at a terrain imbued with ancient meanings, enriched by tradition and ritual, and animated by that which is sacred and ineffable. Poised between the past and present, recollection and reality, the physical and the spiritual, Baker’s chimerical landscapes inspire a poignant commentary on the ways history, social sensibilities, memory, and mythology mediate our experience of nature.

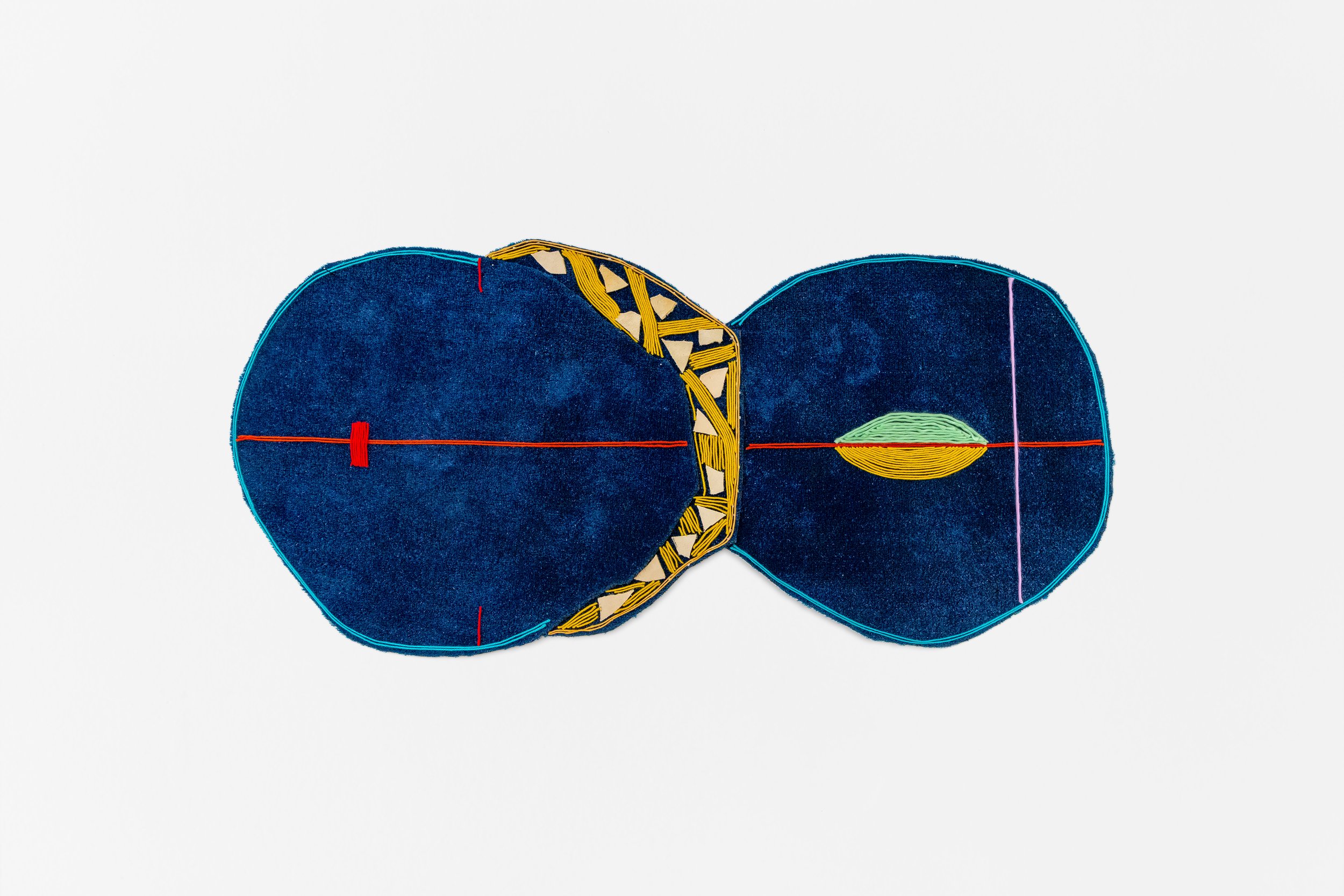

At first glance, the viewer might find the textiles’ base material, Astroturf, surprising. They’d be right to assume that someone raised nomadically across the national parks of the Midwest wouldn’t have had many encounters with the imitation grass. It wasn’t until Baker moved to Texas a few years ago that she discovered the vibrant, short-pile synthetic turf. Sturdy enough to support layers of paint, weavings, sticks, and stones yet malleable enough to be manipulated into unusual, organic shapes, the plastic mats freed her from the rigid constraints of traditional canvas. The mimetic texture, capable of conjuring wide-open plains and vast grassy fields, alleviated the burden of representation and encouraged abstract experimentation.

Perhaps the fiber’s most compelling quality is the tension it enacts with the natural embellishments. The ultra-contemporary turf, indicative of an age beholden to plastic and artifice, tempers the traditional materials and recontextualizes them within a modern discourse. Yarn, willow, and buckskin, resources used for thousands of years by Indigenous peoples, are dispensed like paint to create mesmerizing gestures, patterns, and shapes across the shaggy surface. Despite being restricted to the materiality of yarn to generate variation in her lines and marks, Baker renders a convincingly painterly effect that’s both innovative and recognizable. Nods to certain expressionists, including Mark Rothko and Helen Frankenthaler, can be found throughout the exhibition alongside techniques, patterns, and symbols culled from Mandan and Hidatsa customs and craftsmanship.

While the compositions resist narrative, the haptic engagement with the surface texture, the coloration, and the use of organic shapes ground them in the realm of landscapes and topographical maps. One can identify a winding river in Spring Unforeseen, an island in the middle of a lake in No Walls, or a parched field in Yellow Prairie Grass. At times, the individual threads that bisect the picture plane appear as longitude and latitude lines; other times, they read like hiking trails or the boundaries of various plots of crops. Dappled strands of yarn arranged side by side mimic the fluidity of water, and layers of paint imitate shifting patterns of light and shade. Baker relies on the emotional freight of her color palette to modulate between the feeling of a landscape and the landscape itself. Indigo, as evocative of the ocean and the night sky as it is of melancholy and despair.

Where the materials resist domination, the strings fray, the Astroturf emerges beneath the painted veneer, and the rawhide curls around the edges, the tapestries feel most alive, charged with an energy and agency of their own invention. Even affixed to the gallery walls, there’s a sense of perpetual unfurling as if the works are still engaged in the act of becoming. To see them this way is to see them as products of a dynamic relationship between artist and material, not a subjugation or domination of the former by the latter. The metaphorical jump from the material to the land itself is difficult to ignore, rendering them poignant examples of symbiotic stewardship.

On the afternoon of my visit, a rogue red ant crawled assiduously across the brilliant green field in Unwritten. For just a moment, I experienced that exhilarating awareness of being unfathomably small but fundamentally connected to something unfathomably vast and irrefutably miraculous that I’d previously assumed only the grandeur of nature could provoke.

From Joy to Joy to Joy is on view through October 14 @ de boer 3311 E. Pico Boulevard, Los Angeles