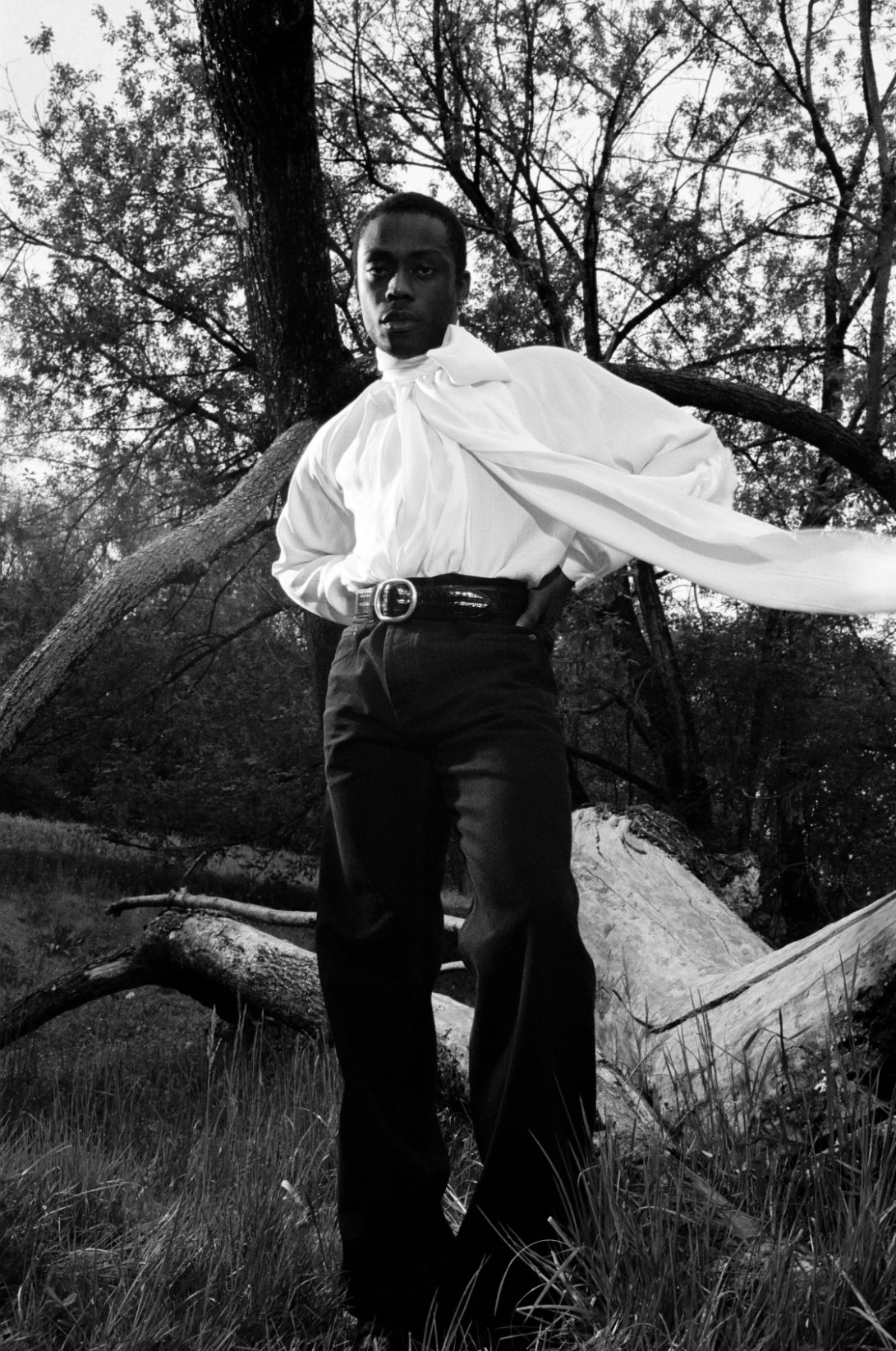

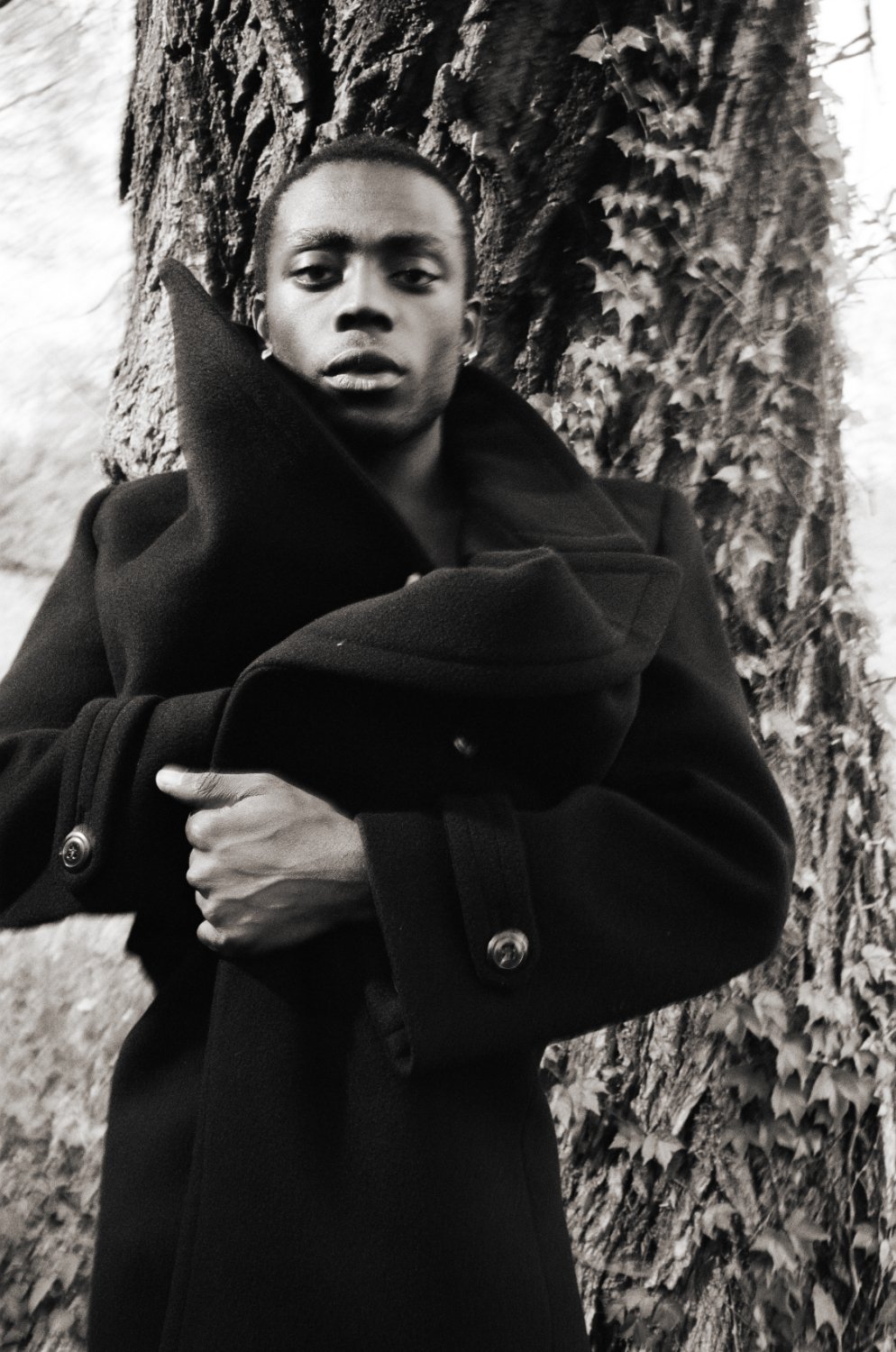

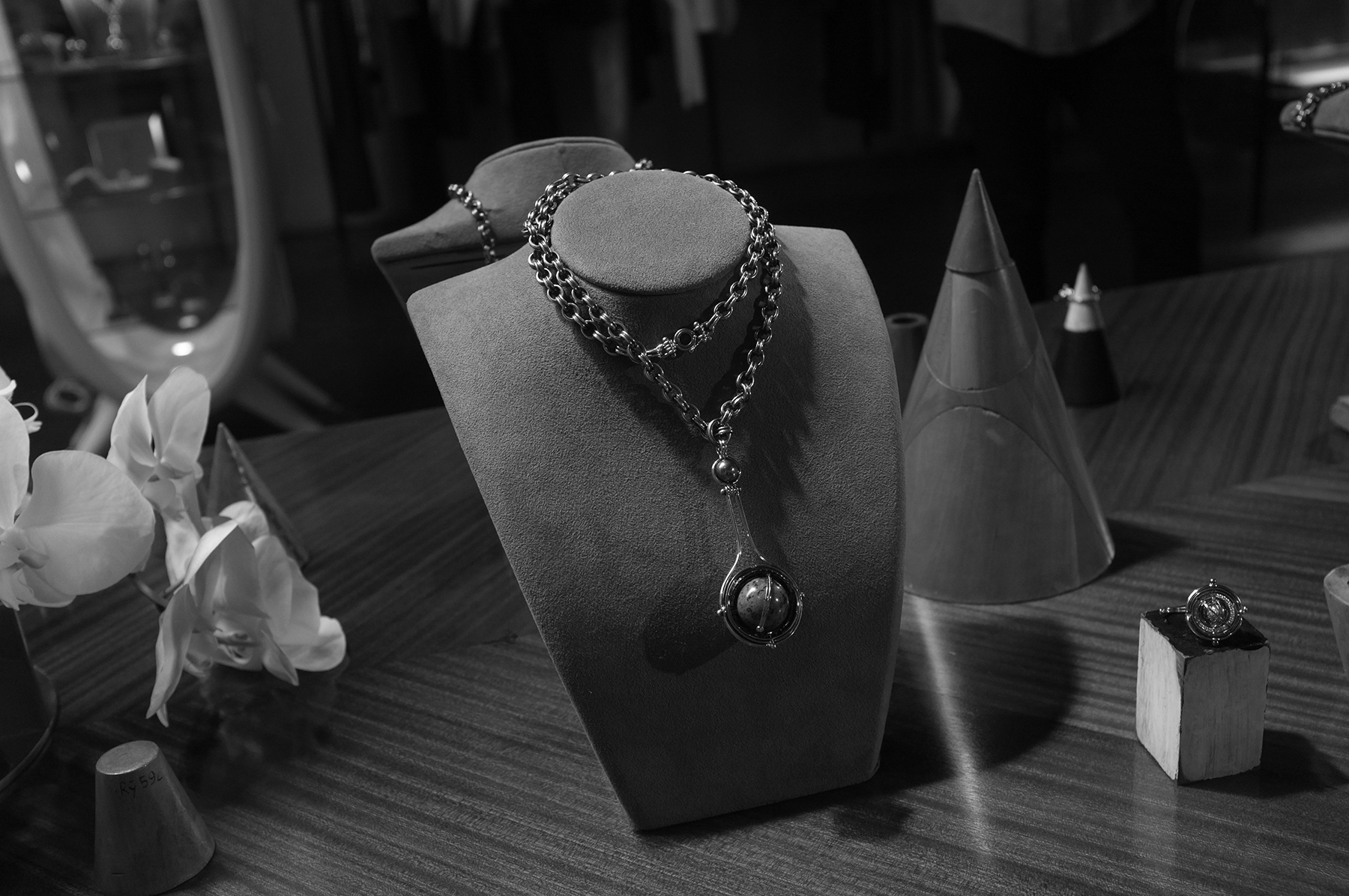

All Mirrors Collection. Photography by Malina Corpadean.

interview by Lola Titilayo

What happens when couture meets code? Montréal-based fashion designer Ying Gao is recognized for consistently pushing the boundaries of fashion through her exploration of fabric manipulation, interactivity, and technology. The use of unconventional materials to make wearable art is prominent in her work, as evidenced in her All Mirrors 2024 collection, made of soft mirrors and 18-karat gold finishing. In 2023, her In Camera collection experimented with reactivity in fashion design by coming to life when photographed. Even as early as 2017, she made waves with interactive fingerprint technology that only recognizes strangers in her Possible Tomorrows collection. The infusion of technology in her work adds a sense of movement and interaction that captivates audiences, and each collection has a special story to tell.

From fashion design to lecturing at the Université du Québec à Montréal, Ying Gao has had an incredibly extensive career already. She also served as head of the fashion, jewelry, and accessories design program at HEAD Genève from 2013 to 2015 and has presented her creative work in over 100 exhibitions around the world with 16 official collections.

LOLA TITILAYO: You’ve developed a unique practice at the intersection of fashion, technology, and philosophy. Could you share how your journey began; where you come from, and how your experiences and background have influenced your fascination with design and innovation?

YING GAO: My path has always been shaped by displacement, between countries, languages, and systems of thought. I grew up between Switzerland and China, between different structures and imagination, in places where order mattered as much as invention. When I discovered fashion, I didn’t see it as an industry, but as a medium for reflection—a way to question materiality and identity. Technology entered naturally, not as a tool of progress but as a means to disturb perception. Montréal, where I live and work now, offers the right distance from the fashion capitals and the freedom to think differently. Here, experimentation is not only tolerated; it is expected.

TITILAYO: Let’s dive into your new work, Charlotte and Everybody Else [2025]. This collection explores faces that don’t exist in the real world, yet seem real enough to deceive recognition systems. What draws you to this boundary between the real and the artificial?

GAO: This work began with a simple question: What if we could create a face that belongs to no one, yet seems entirely plausible? A face that could trick not only a machine, but our own empathy. We live surrounded by systems that authenticate, verify, and categorize. Charlotte and Everybody Else is a reversal of that process; it fabricates illusion until illusion becomes credible. What attracts me is the tension between intimacy and fiction. These faces are ghosts of data, assembled by an algorithm, yet they awaken something human. They are both mirror and mask. I am interested in that brief moment of uncertainty, when recognition collapses, when the image stops being someone and becomes everyone.

Charlotte and Everybody Else. Photography byVincent René Lortie

TITILAYO: This piece is both a critique and a product of algorithmic potential; is technology an ally to you? An adversary, or something in between?

GAO: Technology is neither an ally nor an adversary. It is a medium, a mirror of our collective anxieties and desires. I treat it as a collaborator that resists simplification. It amplifies fragility, exposes our need for control, and sometimes reveals the absurdity of our own systems. When it fails, it becomes poetic. I am interested in this instability, where the machine is not simply an extension of human intention, but an autonomous presence capable of contradiction and failures.

TITILAYO: Fashion often revolves around the idea of creativity and self-expression, while algorithms are more rigid. How do you reconcile these opposing impulses in your work?

GAO: I don’t see them as opposites. Both fashion and algorithms rely on structure, rules, and patterns. What differs is intention. In my work, I let the algorithm introduce resistance into the creative process. It becomes a partner that generates complexity rather than predictability. The garment, in turn, negotiates between intuition and logic. The result is rather a tension.

TITILAYO: Can you talk about the specific technologies used in this project? For example, how do the faces ripple in response to the authentication system?

GAO: The project combines an identification protocol with a responsive surface system. Actuators and translucent composites translate digital uncertainty into physical movement. When the authentication process detects an anomaly, the signal triggers a subtle ripple across the facial surface, a gesture both mechanical and algorithmic. The movement is minimal, but it reveals the system’s doubt, materializing the space between data and uncertainty. The faces do not imitate life; they render visible the fragility of verification itself.

TITILAYO: In your 2024 collection, All Mirrors, you reference Umberto Eco’s idea that “mirrors provide both an impression of virtuality and an impression of reality.” How did you interpret that duality in your work?

GAO: A mirror is always ambiguous; it confirms presence while creating distance. In All Mirrors, I wanted to design garments that behave like mirrors: reflective but porous, tangible yet elusive. They don’t simply return an image; they question it. What you see is never exactly what is there. For me, that duality echoes the way we navigate identity today, oscillating between visibility and erasure, reality and simulation.

All Mirrors Collection. Photography by Malina Corpadean.

TITILAYO: Still on your All Mirrors collection, how do you balance texture, motion, and functionality in your designs?

GAO: These elements form an “ensemble” rather than a hierarchy. Texture is what seduces, motion introduces time, functionality brings everything back to the body. I work with materials that retain a memory of movement, such as soft robotics, as well as reflective and flexible composites. The challenge is to create garments that remain unstable; tactile yet unpredictable.

TITILAYO: To what extent does being based in Montréal shape your perspective on design and technology in your work?

GAO: Being based in Montréal matters deeply. It is not a neutral location; it’s a city between languages, between speeds. I live and think in French, then in English, and in Chinese. This gives a different rhythm to the way I approach design. The French language carries nuance and delay. To me, it resists immediacy. That affects how I build a project, how I let an idea unfold. Montréal is a bilingual city, but for me, it remains profoundly francophone in its sensibility: curious, critical, open, and slightly detached from global acceleration. It’s not a city of excess; it’s a city of negotiation, of hybrid systems. That context allows me to work in the pauses and the intervals. It keeps me alert, and perhaps a little out of step, which I value.

TITILAYO: You’re also a professor at the Université du Québec à Montréal. How has teaching influenced your creative practice, and what subjects do you focus on with your students?

GAO: Teaching keeps me in dialogue with the present. My students move through an excess of images and information, yet they search for meaning within it. Watching how they make sense of this noise forces me to question my own pace. It’s a reciprocal process; their way of seeing redefines mine, and that exchange keeps the work intellectually alive. I teach fashion design in a broad sense, less about trend or style, more about influence and context. We talk about literature, film, and politics as much as about garments, because fashion is always a reflection of its time, its fears, and its desires. What I try to transmit is curiosity and a certain freedom of thought. I want them to see beyond their screens, to connect form with meaning. Teaching reminds me that fashion design should be a social act before it becomes an aesthetic one.

TITILAYO: Do the students inform or challenge your creative process?

GAO: Absolutely. My students question a lot of things, influences, function, intention, meaning. Their curiosity obliges me to revisit my own assumptions. They bring a freshness and urgency that prevents the work from becoming complacent. Their intuition often points to what matters most: how a garment can provoke reflection rather than please.

TITILAYO: What do you envision the future of fashion and technology to look like?

GAO: I imagine a future that is less about spectacle and more about consciousness. Technology will continue to evolve, but the true innovation will come from our ability to use it with restraint. Fashion will not disappear; it will transform into a form of awareness. I see garments as quiet interfaces, capable of remembering, hesitating. The most radical gesture might be simplicity, the ability of a piece to reveal its intelligence without showing it.

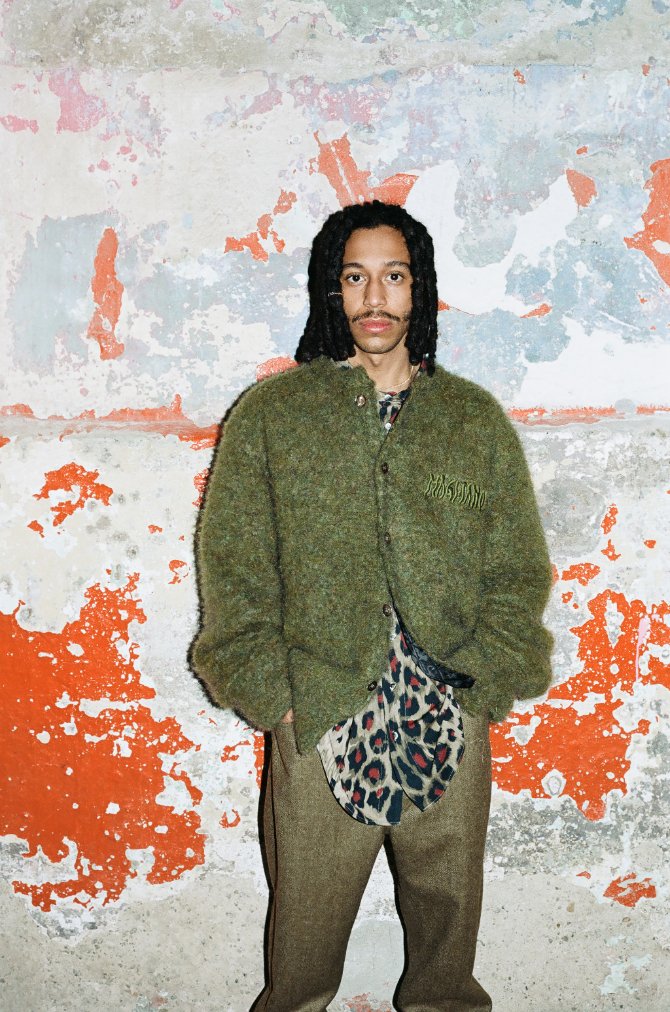

In Camera collection. Photography by Maude Arsenault

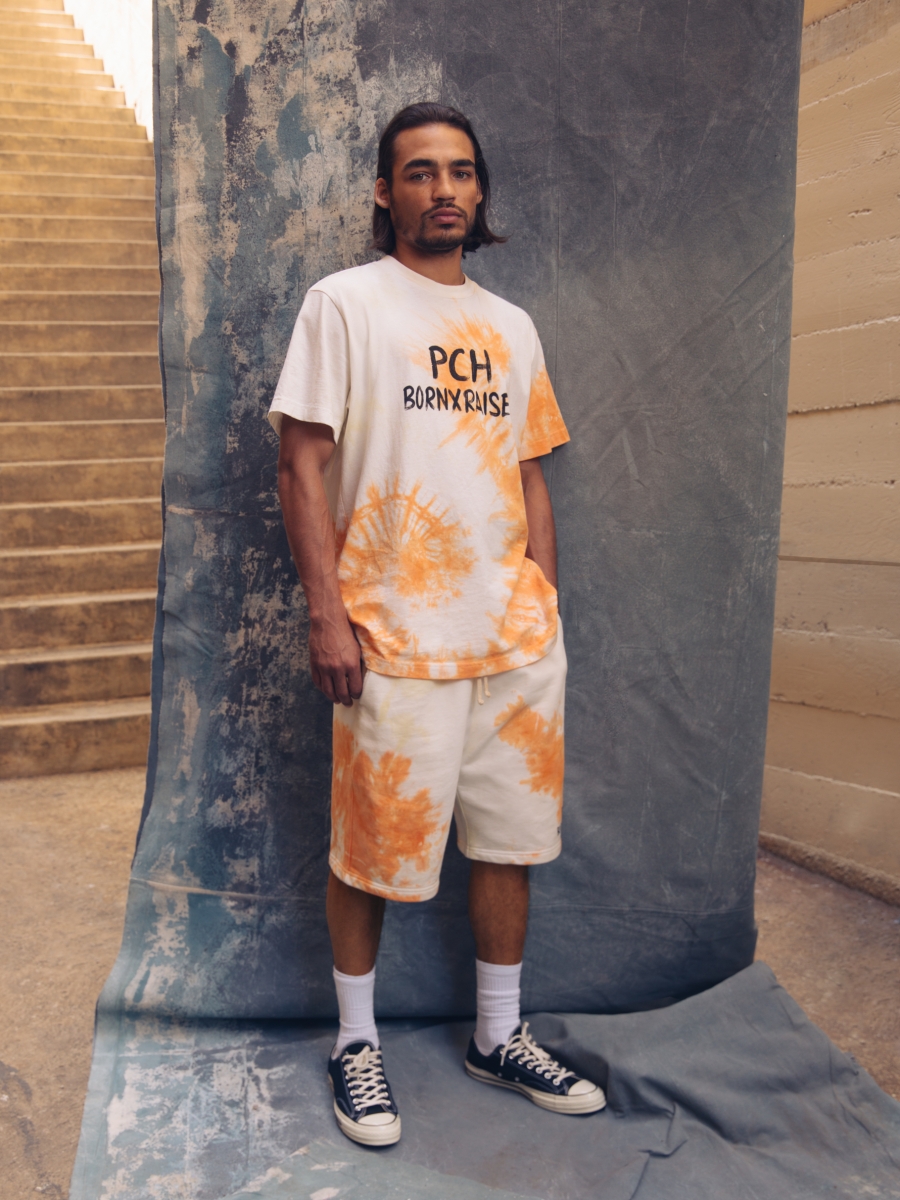

2526 collection. Photography by Maude Arsenault