Interview by Dan Abbe

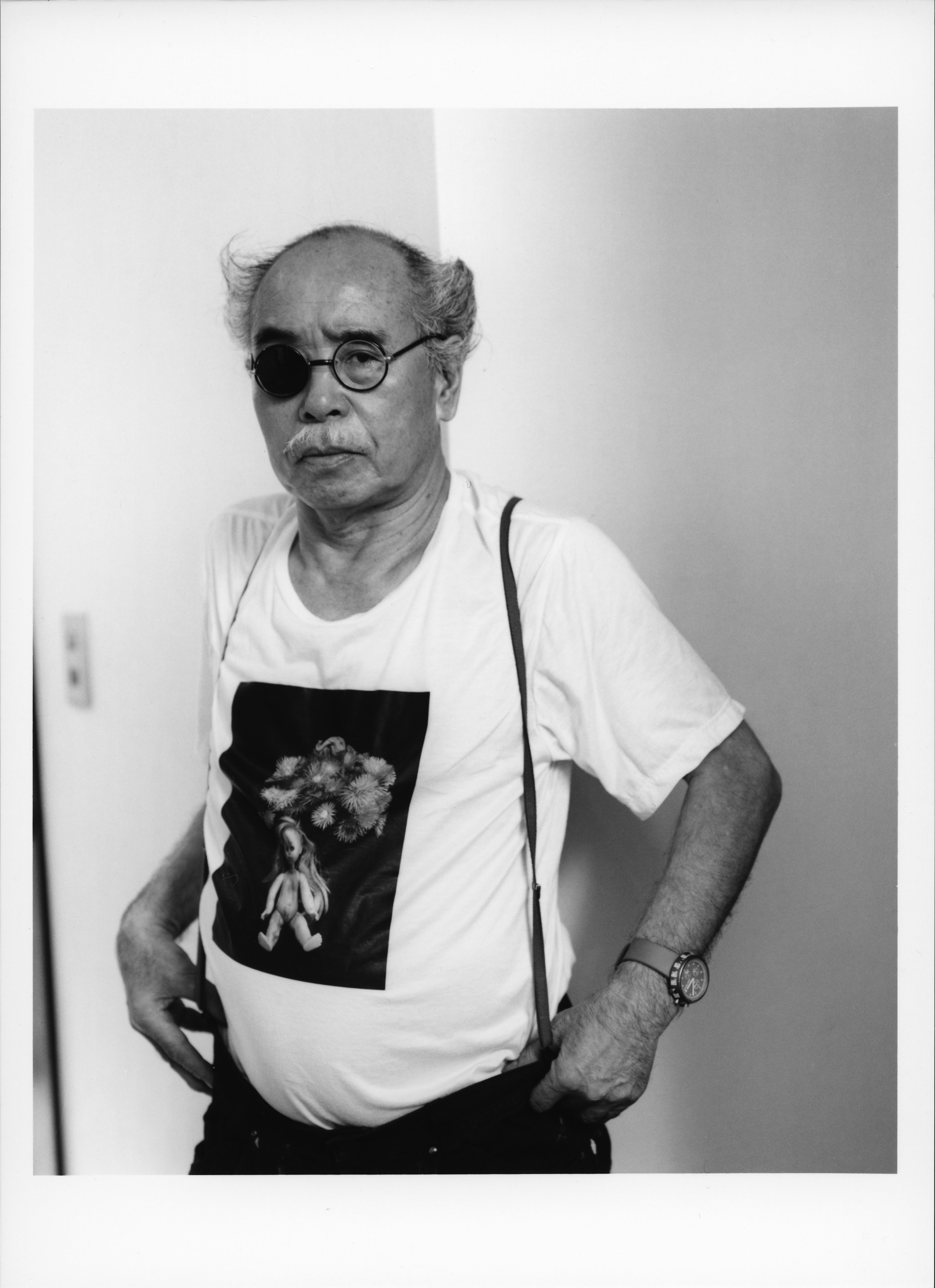

Portraits by Tom Fraud

NOBUYOSHI ARAKI: What kind of questions will you be asking? There’s nothing really to ask, is there? Because my photos are pretty chatty. I'm not joking! They're just the same as talking to me. If I was going to put it in a cool-sounding way, it’s like they translate my subjects as they really are. So, there's really nothing to talk about!

DAN ABBE: [Do you] look at the internet much?

ARAKI: No, I don’t have it. I don’t even own a mobile phone. Nothing like that. I don’t like being shot with a digital camera, especially a really good one. It's too good, you know? I feel like digital cameras miss what’s most important, emotion and wetness. These things get lost in digital photography. And before you know it, you get used to that. I’m not talking about shades or shadows being lost, or anything like that. But I almost feel as if digital photography takes away the shadow of the person taking the photo. That’s why I don’t use digital cameras.

I’d like to ask you about your recent exhibit at the Toyota Municipal Museum of Art, "Ojo Shashu: Photography for the Afterlife." How do you think it went, either in terms of the content, or the reaction from the audience?

The museum tried to make it seem like I was dead. For me, putting something together always means pulling it apart. For this exhibit, it worked, though. I mean, the museum is designed well, as a place to show photographs. When I first started, I thought that photographs should be shown in books, not in museums. At that time, I thought that museums were like graveyards, at least for photography, you know. This exhibit was good. Presenting my works in an exhibit like that instead of through a photo book, I feel like I was able to express myself even better. It’s like climbing Mount Fuji—it’s usually better to see the sunrise from the 8th station, but for this exhibit we went straight to the top.

Did you try out anything in particular with the presentation of your work?

I try to switch things up to make it look as rough around the edges as possible. You know those people who pay really careful attention to the way their works are exhibited? Like, some photographers focus on the layout too much. That’s wrong. It should just be slapped together. I didn’t even put the photos up myself. I entrusted all that to people who understand me well—I just said, "do it however you want." It was a success. I’ve always acted on the principle of pulling everything apart and always presenting something new.

The next exhibition I’m doing is called Ai No Tabi [Love Journey] in Niigata Prefecture. (pointing out a photo in the catalog) This one is of my balcony when I was living in Gotokuji. This is the western sky. Heaven, in other words. Around March 11, 2011, my apartment building was demolished, so I moved to Umegaoka, a neighborhood close by. I did up the rooftop and began shooting the eastern sky from there. That’s where the sun rises, you know, reborn. In this sense, I take photographs in the same way that I live my life.

It’s not just a simple shot of the eastern sky; it’s loaded with my feeling that everything starts from there. Let me tell you something: as you can see, the sky in the east gets darker and darker. Now look closer, and it becomes a mirror, or a window of myself. Before March 11, 2011, I had to face my father’s death, my mother's death and my wife’s death. Then around March 11, my cat Chiro died. So recently, the Grim Reaper has been hovering around here. And over there is a goddess (gestures at the woman sitting next to him) so these days it's the three of us! (laughs) I got prostate cancer and did radiotherapy, which messed this up (points towards his pelvis) and made me piss blood. Then I lost sight in one of my eyes. The blood in my urine is from the radiotherapy. But I also had a circulatory problem, a blocked artery, so now I’m taking a blood-thinning agent, but it's thinning too much and making me piss blood. So here I am going through all this, and now you want to ask me these questions! (all laugh)

Your exhibit "Sagan No Koi [Love on the Left Eye]" was showing at Taka Ishii Gallery recently...

Yeah, I took the title from van der Elsken's "Seine Sagan No Koi [Love on the Left Bank]." It could have been Love on the Sumida River for all I care. My wife loved "Love on the Left Bank" too. I was a fan of his work when I was around 20. I guess I’m paying homage, or really just playing around. What did you think of it?

I thought it could be appreciated as painting, too. The show that's up there now [an exhibit by Kunié Sugiura] also combines photography and painting, so there’s a connection. Anyway, I was interested in the gaps where the light breaks through the paint a little bit.

That’s what’s great about those works. That you can kind of see them, but you also can’t. After this, I thought about painting over the left half as well, and calling it "Light and Darkness Lost." Light and Darkness is Natsume Soseki’s posthumous novel. It seems like a waste, but I painted over photographs of nudes and so on in black. Still, if I went too far, it would seem like I was trying to do some sort of trendy art, so I’m holding back. It's tough though, my genius makes me do these things! (laughs)

I want to talk about your recent work. Every time you produce something new, you do it under the name Araki, which means that the bar is always set high. Yet I think you’ve been clearing it each time, and I wonder whether people don’t think: "well, it's Araki, so of course it’s going to be good." Do you think you’re taken for granted?

I mean, I’ve decided that I must do something different every time. If I don't keep transforming, I’ll just become a master. It's no good being a maestro. (laughs) I always want to work as if I’m a novice. I never want to reproduce or reshoot anything I've already done. I do always say that photography is about reproducing, for instance the reproduction of a person, or the reproduction of an era, reproduction this, reproduction that, but actually I think it's bad to keep reproducing your own work.

I actually wanted to ask you about this word reproduction, or replication. The same subjects often appear in your work, and I wonder whether you would also consider that to be a kind of replication, too. Based on what you just said, though, I’m guessing no.

That's right. So his style is a little different, but it’s like looking head-on at a Picasso painting. (looks at the woman next to him) From a different angle, she looks Chinese, different. From the front, the back, at an angle.... What you see and what you feel is up to you. My subjects are multifaceted, and that’s what I find appealing, that they’re appealing in different ways. When I photograph a woman, I see many different sides to her.

Is the sky similar as a subject in that it's different every time?

Yes. To me, that's why it's "heavenly." There are no two skies that look the same. Later, I will exhibit “Eastern Sky” at Shiseido Gallery. I’ve been shooting the sky every morning for nearly three years, since I moved to my new apartment after March 11.

But you know, when it comes to showing these photos.... It’s not like I think the audience won’t understand, or that I would be making fun of them, but shooting photos and showing them are two different things. When you exhibit, you should have at least some entertainment.

For example, I do this thing that I call "kurumado" [this is a portmanteau of the Japanese words for “car,” kuruma, and “window,” mado] where I shoot from the inside of a taxi. Everything looks great from the window now. I used to photograph all the time, but looking makes me more tired now, because I can only see with one eye. So now, I only shoot when my taxi stops at a red light. When I stop at a red light, the shot is framed perfectly by the side window, because the photography gods are on my side.

But anyway, when I show these photos of basically nothing to an audience, I feel like I should make it more entertaining by throwing in some nudes here and there, even though I call my work "Shi-shashin" [I-photography].

The content of these three shows in Aichi, Niigata and Tokyo are all very different.

Yeah, it’s not a “traveling exhibition,” I don't do that.

Because that would be a repetition?

Yes, yes. Otherwise it’s like, “Oh, I saw the same thing in that city too.”

Are you making three different catalogs too?

No, just one. There are going to be some photos in the Niigata section of the book that didn’t even make it into the actual exhibit. Also, I’m only using one photo from the Eastern Sky exhibit I’ll be doing at Shiseido. I took it on New Year's Day, this year.

I bet something's going to happen within this year. Like a nuclear power plant or Mount Fuji is going to blow, something like that. It won't be a reborn eastern sky anymore. I feel like the entire sky—north, south, east, west—is beginning to resemble the western sky, in other words heaven. Still, I want to live to be over eighty. That’s how my photos make me feel. They encourage me. The sky that I’m looking at right now has become a mirror.

What’s the difference between the eastern and western skies?

Ah. It's very chatty, you know, the western sky. A real loudmouth. In the olden days, it was considered to be the Pure Land. It’s where the sun sets, and when it does, it’s quite dramatic. I think life’s the same way too.

The sun rises in the east, so I thought that the eastern sky was flat, because of all this backlight. But these days, it's getting more complicated. Perhaps because of El Niño, what the hell do I know!

Here's the interesting thing, though. Because I’m shooting against the light, the bumpy tops of those buildings look like graves, or gravestones. You could almost say it’s like a graveyard sky. You look at the sky, you look at the heavens, you look at the world. And see, that’s where the road is. When I see roads, I feel like they’re life itself. At every moment.

Mornings from 7 to 8 am, there’s always a girl running in high heels, click clack click. If only she’d leave the house a little earlier, then she wouldn’t have to rush, and the station is so close, too! Someone's walking their dog, and there are families and married couples. I’ve been shooting the same scenery for three years, so now there’s room to think thoughts like “I wish I saw new couples instead of the usual ones.” Or “I wish he’d get a different girlfriend.” That’s what I think about when I’m shooting. (laughs) You can see the essence of this whole year in these photos. (points to a section of the catalog)

So these are all photos you took from your rooftop?

That’s right. I’m making a photo book entirely of this series. It’ll be out in a month or so. But without anything else, I think it will be kind of boring for the poor saps looking at it! (laughs)

But you’re not bored of them yourself, are you.

Oh, nowadays this is all I need! It’s a bad example, but they're better than Balthus’ road. ["Le Passage du Commerce-Saint-André"]

In Japan, words like “path” [michi] or “sky” can easily take on deeper meanings. That’s why I’m using the word “road” [doro]. If you say “path,” people might take this to be spiritual or symbolic, they might think of paths with no one in sight, or a painting by Kaii Higashiyama, and this is not what I’m going for. I want to say that everyday things can tell us a lot about everything. It’s the everyday that’s alive. That's why I shoot every single day.

So every day without fail, you shoot the sky and the road from your rooftop. Is there anything else that you do every day?

People often decide this kind of thing, right? Like, "I'm going to shoot such and such a thing." If I had that kind of time, I’d rather just take photos of myself. That's why I take “I-photographs.” You have to keep on breathing, keep your heart pumping, and in my case clicking the shutter is the same thing. That's why I'm not going to go photograph a war, or something like that.

It's weird to say I’m moved, but I guess I'm most affected by things like pissing blood. When things like that happen, the first thing I think is to grab my camera. That’s what I’ve been doing for about fifty years. (laughs)

I wanted to ask you about something I read in the remembrance you wrote for Shomei Tomatsu, in which you said that he'd influenced you in terms of your thoughts about history, or politics.

Oh, I wouldn't write that. "politics" and such. I think it depends on when you were born. He was born 10 years before me, so he was hung up about the fact that we were occupied, that's why he went to Yokosuka and Okinawa. I’m personally more hung up about things like the atomic bomb. I shoot a lot in August: the 6th, the 9th, Nagasaki, and the 15th, the day the war ended. When I was working on Pseudo Diary, I messed with the camera's dating feature, so in some sense I have an obsession about this, or about the Showa Emperor. Again, this all depends on when you were born. On August 15, I would, without fail, go to the Imperial Palace and shoot. I was really into that. I have a thing for the date August 15. I would change the date of the camera to August 15, take regular photos of daily life, and some other meaning would appear. March 11 overlaps with the atomic bomb in my mind.

Right, I mean you've said that your photographs are all about yourself, but I think that March 11 has become a surprisingly big theme for you.

It's influenced me, yes—but it's more like I’ve had no choice but to be influenced. It’s probably the influence closest to me personally, strange as that may sound. But it was its own expression. Photographers, you know, aren't people who express things. It's the world that does the expressing. Time, too.

One role of photographers is to respond to such expressions through shooting. I'm not like that, though. Even now I sometimes think maybe I should have gone, but I'm the kind of photographer that squeals out, "nice!" when I shoot. As a photographer, it would've been a fantastic landscape—a boat sitting on top of a love hotel—but I wouldn't have been able to keep my mouth shut. I get like that when I hold a camera. So that's why I couldn’t go, didn't go.

So many photographers have gone to Tohoku and taken photographs, but personally I'm not sure it's adding up to much.

Well, I basically don’t look at other people’s photos. It’s not that I’m cynical, but I’m interested in other things, like the silly people trying to save this lone pine tree that miraculously survived. That’s the kind of thing that I’m interested in. It's kind of a goofy or foolish thing, but it's really interesting to me.

Okay, let's talk about the sky again. You're now facing towards the east, but as far as I know Tokyo Skytree has never appeared in your work. Is that intentional?

I’m loyal to Tokyo Tower, I grew up with it. I went up Skytree for a job, but it was cloudy that day so it didn't even matter!

I’m worried that Skytree will ruin the shitamachi [Tokyo's older district] by turning it into a regular place. Of course Tokyo is always changing, but I wonder how you feel about this.

Cities are always changing, and I don’t necessarily think that’s a bad thing. Even if it does become all digitized, I don’t mind the idea of a digital shitamachi.

I don’t like photos that don’t have a feeling of nostalgia. Nostalgia lasts forever. Even if you can’t see it, nostalgia remains. People look down on nostalgia and sentimentality, right? Like they're not virile. Tears are good.

Everyone is losing touch with this kind of thing. Not just in photography, you know, but in the way they're relating to each other. I mean, what is this—Twitter and so on. Pick up a damn brush and write out the characters! (laughs) That’s why people get frustrated and stab one another, because their words aren’t getting through to others. That's something good about the shitamachi though. You can see siblings going to calligraphy classes together after school. Ah, I just love that, I can't contain myself. It’s so great.

(Araki looks through the catalog)

A little while ago I said "Light and Darkness Lost," making a joke out of Soseki's Light and Darkness, but I’m not necessarily inspired by literature. It’s the photos I take subconsciously that teach me the most. I took a photo of a cat’s shadow, you see? (picks out an image in the catalog) That’s because I felt that there might be more truth in its shadow. Regardless of whether that’s the right thing or not. There are some men who prefer shadows to bodies, you know. (laughs)

Something I like about your work is that it's extremely pure, but it’s not naïve. I mean, this is sort of a strange thing to say, but I have this idea that your mind is more Greek than Japanese. Before you mentioned how tears are good, right? A few years ago, when I saw your exhibit about Chiro, Sentimental Journey, Spring Journey at Rat Hole Gallery, I was so overcome with emotion that I nearly burst out into tears right there. It feels to me like you relate to things, whether animal or human, in an almost cosmic way.

With Chiro, if you look at those photographs you can see that her feelings towards me were much stronger than my feelings towards her. I did not respond enough to her love. Her love was deeper than mine. The photographs make this clear. Look at her final portrait, when she gazed at me. I just feel that my love was weak. That's why the photographs of Chiro are good. My photos have always been about my relationship with the partner in front of me.

How about the people looking at your work—what sort of "partner" are they?

I’m not so concerned about them. For me, it’s all about the subject in the photo and nothing else. That’s why, when I present my works, I feel like I need to add an element of entertainment for the audience, even if it's a lie.

(showing images of Chiro) This is when she’s so thin that they can’t even find a place to put a drip in her arm. I asked her to stand one last time for a photo, and she did. But you know what? This face, with her eyes closed, when she was dead—that was the most beautiful shot.

Here, she’s already got rigor mortis. It sets in immediately after death, you know. That’s why she’s the same shape. (shows Chiro after cremation) I told them [i.e. the crematorium staff] to keep her in this position.

Here I’ve painted onto the sky. (points at an image) I made these works for the exhibition one year after Yoko's death. It's a pity to exhibit black and white photographs on white walls, so I created a sky dedicated to her. A sunrise or sunset, a sky for her. I can’t help it, I’m naturally gifted. These are great, aren't they? (laughs)

I’m curious to ask about Setsuko Hara, who has appeared in your work a few times—

Yes indeed! That big-boned, Russian-looking woman. There's the word sonzaikan ["presence"], but I have a particular term that I use when I’m referring to a woman, nyozaikan [a portmanteau of the Japanese words for “woman,” nyo, and “presence”], and she had it. She isn’t cute or sexy at all, but I like women who are full of resentment, who have some poison in them, and I was attracted to those qualities in her.

In that sense, what do you think about the girls of AKB48?

They’re all the same... That’s what I'd call “digital.” It's okay for what it is. They’re all cute, and that's not bad, no? But there are girls from the same generation who exist in a different realm from AKB48, and I think they're amazing. The AKB girls are manufactured. I guess some people will find them interesting, though.

But they're not your liking?

Oh, some of them I like. (laughs) But they all look the same to me. I’ve shot some of them, too. In thinking about what I would want to shoot, my own mettle came out. So, you had Atsuko Maeda and Yuko Oshima. In the election, Oshima had won—

You're surprisingly familiar with this!

So I thought I’d get some sort of reaction if I made them stand side by side, and in fact there's one shot where they're almost wrapped up together. You could just feel their rivalry. That's interesting to me, to shoot two people in that kind of situation.

Let’s talk a little bit about foreign countries. What has the response to your work been abroad?

People overseas responded to my work immediately. When I showed Akt-Tokyo in Europe, the photos spoke for me, especially since I didn’t speak the language. It convinced me that photos are better than words.

Do you think that Japanese photography culture has anything to teach overseas?

Probably not, right? (laughs) Anyway, it’s not about teaching or being taught—as long as you’re ready to learn from your subjects, you’ll definitely be fine. And by the way, everything around you is fantastic.

Overseas, they try to force all this emotion into the frame, right? But it’s better to think of the frame as something from which emotions and such can escape easily.

How would you look back on your experience as a judge for the Canon New Cosmos competition? In some sense, you helped shape an era.

I've been bashing digital today, but these days, digital shots that people take of friends of friends seem to be valued pretty highly. Maybe that’s because I used to select those kinds of photos all the time at the competition, though I selected other things too.

We had guest judges sometimes, like the director of a photography museum in Paris. He told me that he understood my photos, but that he didn’t understand the photos I'd selected as a judge. You know, people like HIROMIX.

I mean, the stuff that guy selected was amazing! A reflection of the moon in a pond, that kind of thing. Come on! (all laugh) So I guess it's not surprising that, coming in as a guest judge, he couldn't understand photographs taken by young Japanese girls. Maybe that work could tell him something like, "Hey, dad, this is how photography is really done!"

˚