intro by Chimera Mohammadi

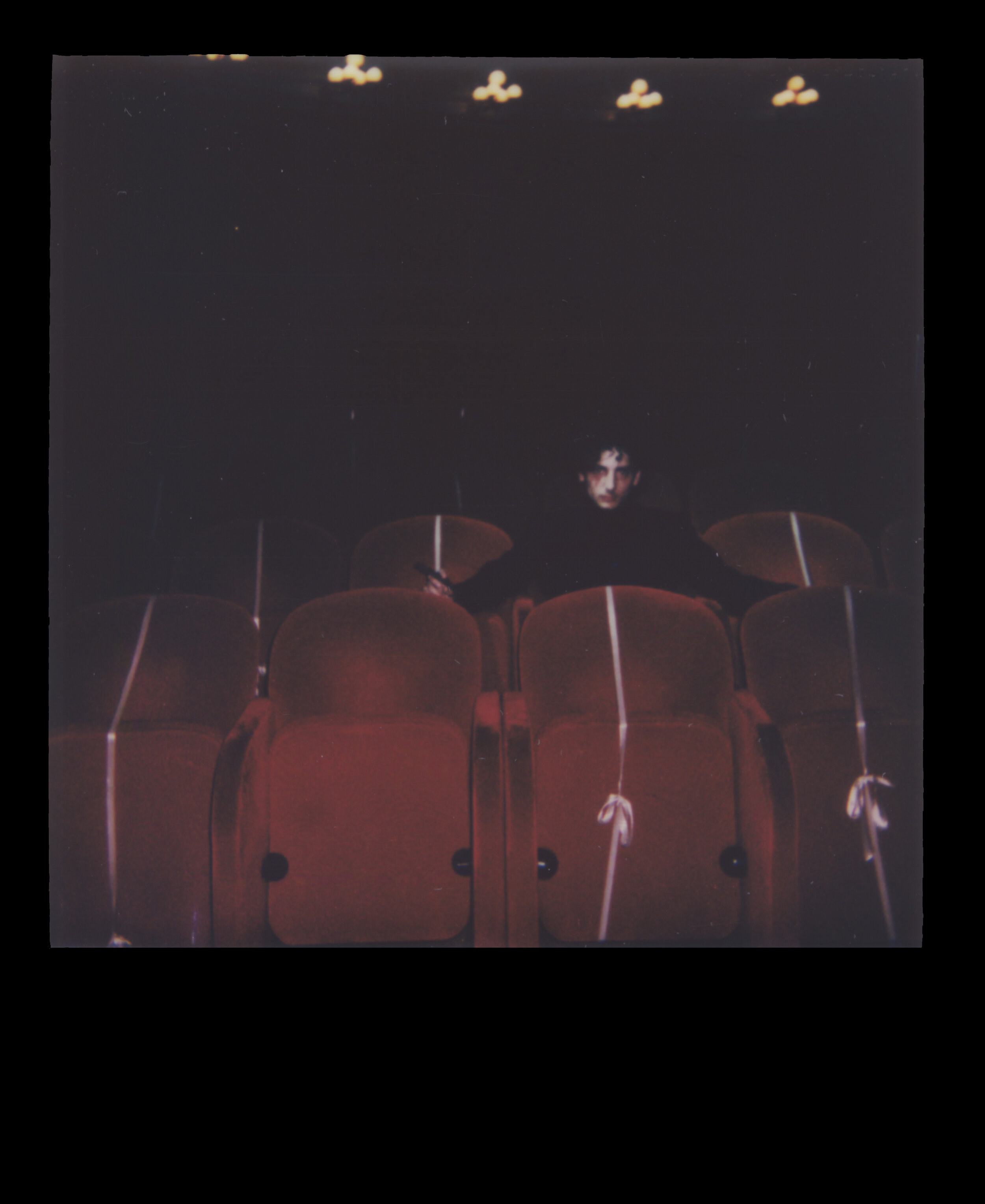

stills from Dog (2024)

In Benjamin Tan’s 2024 short film, Dog, teenage angst sizzles from the screen in a haze of rave-flavored smoke almost thick enough to make you cough. Tan speaks with filmmaker Catherine Hardwicke–who described and shaped generations of adolescent fantasies and fears with movies like Thirteen (2003), Lords of Dogtown (2005), and Twilight (2008)–to identify the strains of terror, rebellion, and self-destruction that combine to infuse the atmospheres of their movies with punch-drunk drama. Dog exists only in tight, black and white images of raves, bedrooms, and cars, which are so myopic that each small scene expands into a massive world, capturing a hedonistic sense of frightening abandon by allowing each moment to become all-consuming. Hardwicke also harnesses deprivation to produce abundance, her coming-of-age stories defined by a similar smallness as limited backdrops make up the vastness of young adult worlds. The limitations of their settings go from comfortingly controlled to claustrophobically constrictive as bacchanalian exploration leads down dark, dead-end roads. Tan and Hardwicke’s films are astonishing for their abilities to capture the unbound possibility of youth culture and keep the camera trained when the carcass of promise begins to rot and fester in its fishnets and kandi bracelets. In conversation, the creators turn their gazes on their own explosive entrances to adulthood, sifting through memories of predators, secrecy, and ecstasy, cataloging the bruises and scars they passed down to their protagonists.

BEN TAN: I watched Thirteen for the first time when I was in middle school. It’s such an honest depiction of teenagers, and it was the first time I watched a film where the characters mirrored my own experiences.

CATHERINE HARDWICKE: Yeah, that was definitely the idea: to make it feel like you were just living like Nikki Reed was living at the time. I would go over to her house and film, with my little video camera, a war between her and her mom. We hadn't really seen what was really going on with teenage girls and all the stress and struggle and peer pressure and all that crazy shit. I went and volunteered at Nikki’s middle school and I saw wild behavior. I saw the teacher trying to wrangle out-of-control students with cell phones running around and guys calling girls pretty outrageous things right there out loud in class. And I thought, this is a lot to deal with. Do people really understand what's going on in a nice school?

TAN: Did you have a rebellious childhood?

HARDWICKE: Everybody kind of has to, a little bit. I grew up in South Texas and it was a very different environment. We would be on the Rio Grande River doing crazy stuff like rope slings. There would be snakes there. There would be 12ft alligator guards. It was a very rowdy childhood. Like, “We're gonna swim across the river. We're gonna run around in Mexico, illegal entry.”

TAN: So you were like an adrenaline junkie.

HARDWICKE: Exactly. If you had bruises on you, you know you had fun. If you didn't, you were a wimp. I guess it’s its own form of rebellion. Rebellion against ordinary life. Boredom.

TAN: I grew up skateboarding and Jackass was a big influence on my brothers and I. We’d blow shit up on our street or skate off roofs. Just be completely crazy kids. I feel like my destructive childhood formed my creative adulthood.

HARDWICKE: I kind of feel lucky that I had crazy adventures as a kid. When you make something very specific, which you did in Dog, it's more relatable to people. I was amazed how you had a very complex relationship with the mother and the sister established almost in 30 seconds. And you're curious and it's a mystery. What is going on? We're drawn into it right away. I think it was so fascinating that you created this kind of mystery at the beginning about the sister and then we start to reveal it. Some people might not even realize that she's blind until the touching game.

TAN: Yeah, I wanted the opening to set things up quickly but be subtle enough, leaving some mystery for the audience to discover the characters.

HARDWICKE: Well, it helps. You keep leaning in. There's something a little off. You're curious. I want to know more. Keeps you in with the film. I like that. Did you feel like you based these on real people that you knew?

TAN: I went to raves at a really young age, like 11. I fell in love with the music right away. At a rave, you can have a profound spiritual experience but there's an element of danger just around the corner. It’s not based on anyone in particular, but I wanted to express the anxiety I felt as a teenager. I always felt like something could go wrong at any moment, or worse, my parents would discover my secrets.

HARDWICKE: It's not the most safe environment.

TAN: But the older sister is more experienced.

HARDWICKE: She knows not to drink the voodoo juice. Even if you try to be the best big sister you can be, something else could happen.

TAN: And when you’re a teenager and something bad happens to you, you don't want to share it with anyone. We default to keeping secrets because we want to protect the people that we love from our own pain. We don’t want to inflict it on anyone else.

HARDWICKE: Wow. Yeah, that's intense.

TAN: I think I see a lot of similarities with Thirteen. Tracy pushes away her mother to hide her pain.

HARDWICKE: She's secretly cutting and doesn’t tell her mother, but that takes great pains to hide it.

TAN: In my middle school, raver girls would wear kandi bracelets they’d make and they’d say things like “love” and “peace” but underneath they were hiding the scars on their wrists.

HARDWICKE: There's a lot of irony built into that. Talk to me about the music and how you wove the music and when you chose to use it.

TAN: Austin Feinstein made the score. I showed him some scenes and he made two demo songs that I placed in the areas where I thought needed music. It worked right away. He tried to convince me to use no score because he thought that the film was stronger without music, but his music really sets the mood.

HARDWICKE: But you were always going to have it in the rave.

TAN: That's true. The rave music was a song from a Scottish techno DJ called Franck. I wanted to have authentic techno, so I reached out to him. and he let us use his song.

HARDWICKE: Oh, that's so cool.

TAN: When you were shooting Thirteen, did you rearrange the dialogue and edit things on the day? How much did you execute that script by the book?

HARDWICKE: What we did is, we wrote it standing up. I had been observing, having her friends over at my house all the time for surf and skate camps and slumber parties and going to her house and going to the schools and all that. So I was kind of like taking all this in, absorbing the scenes that I thought were interesting. I'd say, “Let's improv out a scene. Let’s do a scene where you came home from school and your mom says this. I’ll play your mom, you play yourself.” And then as soon as we finished acting, I would write it up the best we could and put it into the screenplay. But during the rehearsal process, I’d schedule the scenes that I was the most worried about. And I said, let's work on the big confrontational scene. We would try it out. If people felt like their words were clunky or not natural, say it in your own words, inner monologue, what are you really feeling? Say what's in the script now that we've talked through it all and we felt it. Sometimes those inner monologues, those improvs would give a great line that needs to be in. Sometimes it's just an exercise to connect you to the material. Sometimes there's something great that happens.

TAN: When we shot Dog, Alexis Felix, who plays Summer, was giving her mom a quick rundown of Meisner technique just hours before we shot her scenes. They were changing the script so their argument was in their own words, making it more natural. It definitely sounded better. Her mom had never acted before but I casted her because that chemistry and history is already there and I've witnessed them have a heated debate more than one time.

HARDWICKE: Which is kind of great because you could feel it. There's this built in tension. There's little trigger points that everybody has. When you made Dog, did you rehearse?

TAN: We only rehearsed the long scene where Tommy is flirting with Lex, and Summer feels the need to intervene. Tommy is on molly, so he’s not thinking rationally. Also, we don’t fully know Tommy and Summer’s past. One thing we did in the rehearsal process was create a backstory between Summer and Tommy and the relationship that they had. That backstory that we created really guided the nuances of that scene.

HARDWICKE: I thought it was really effective. Certainly in Thirteen, there's the backstory and all the different things, her mother’s struggle with addiction and what her relationship with the mother's ex-boyfriend was. Even in Twilight, we rehearsed scenes of Bella with her father and her mother when her parents told her, we're getting divorced. We played improv scenes where Bella hung out with her dad at Disneyland when she was 13 years old, and super awkward. None of that is in the movie, of course, or even in the books. Just the fact that the actors had that sense memory. That informs the scene.

TAN: Wow, yeah, you can definitely feel it. I love your use of color. How Thirteen takes on a blue melancholic tone as the relationships become more conflicted. And how the ending scene with the sunrise resets everything and allows the color back into their life. Was that something that you thought of early on or did you kind of discover that in post?

HARDWICKE: I was thinking a lot of this movie, 60% or 70%, is going to be in a house and a lot of it's going to be in one bedroom. I thought, how is that going to be interesting? How does the light change? How could the movie stay alive? It's kind of an emotional rollercoaster with the color. It’s normal and bland lighting at the beginning. Then, when Evie comes into her life, it's glowing. We start cranking up the chroma a bit when she starts doing drugs and experimenting. So there's a bit more exaggeration to the colors. When they break up, the color starts draining out. The color goes away back to the blue grays and finally the end when the sun comes up. You made an absolutely beautiful movie in black and white. Why did you choose black and white?

TAN: I wanted to remove a sense from the audience as a reminder that Lex, the blind character, is missing a sense too. Also, there is the notion that dogs see in black and white. Besides setting a mood quickly, these examples were compelling reasons that I felt motivated the aesthetic. Also, I think that showing it in black and white kind of enhances the imagination of what could be in the setting. When you take the color away, the scale of the rave looks so much bigger.

HARDWICKE: I think so too. I used to be a production designer, and when I didn't have enough money to control or create the world the way I wanted to, I would often be asking, “Could we make this in black and white?” I think it's very smart. You created a beautiful, unified look. I thought it worked emotionally. And I thought it was exciting to be in a rave without color because now you have to think about other parts of a rave. You're thinking more about the music, the rhythm, the other elements.