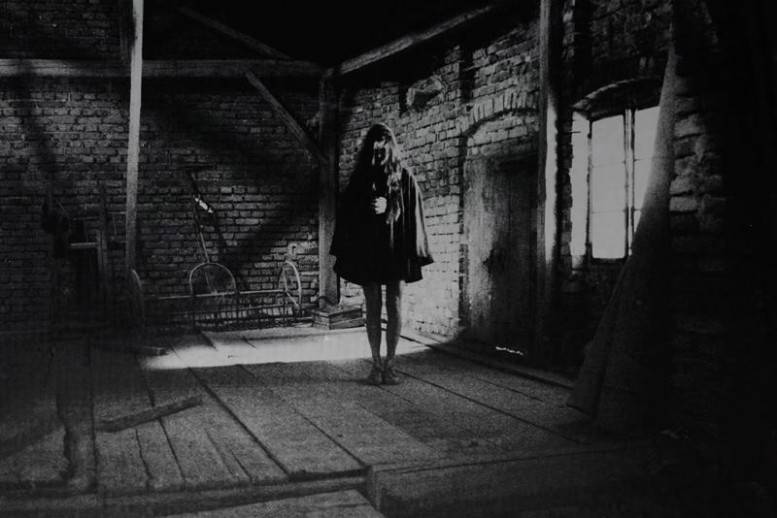

“Living in New York City… has taught me to be extremely compact and intentional about the things I carry with me,” says Maximum Henry Cohen, the slight, unassuming 22-year-old mastermind behind Brooklyn-based leather goods brand Maximum Henry. “There’s a lot of baggage that we carry around with us out of habit.” Cohen is sipping Coca-Cola from a glass bottle, sitting in one of the sweeping factory windows of his Williamsburg waterfront studio, a loft space shared by a few other artisans and draftsmen. In the background, the dull hum of various machines cutting wood and shaping metal creates a strangely comforting white noise. Outside, a tranquil snow of the early-March variety falls on red brick scrawled with graffiti. One of Cohen’s goals in creating his own artisan leather goods brand was to downsize, to eliminate that unnecessary extra baggage, “to make something... that someone could carry and really consider their own.” Everything about Cohen—from his humble, down-to-earth personality to his streamlined workspace to his pared-down website to his handmade business cards— suggests an understated elegance. He pays the utmost attention to detail in the creation of his rustic yet sleek (and amazingly affordable) wallets and belts. “I was… that kid who would make duct tape wallets in the seventh grade and sell them to his friends,” Cohen remembers. Eventually, he set out to make the perfect leather wallet; a wallet that was just big enough to fit everything he needed but nothing more. Beginning in his bedroom with some scissors and a pair of discarded leather shorts that he rescued from their bleak thrift-store fate, he eventually moved into his living room and finally to his own studio, a modest space carefully curated in accordance with his taste for the basic and pure. A weathered steel architect’s lamp casts warm light over the dye-stained wood of his leatherworking table, over which a Singer sewing machine, a relic of vintage Americana, presides. Various tools are arranged neatly above the table, held upright by a homemade leather strap. He keeps his sheets of leather in a beautiful old footlocker and his finished belts, hung from hooks high above his drafting table, cast long shadows on the white walls of the studio. The objects Cohen crafts are simple, functional, full of charm and integrity—the kind of objects one wears or carries for years on end until those objects almost become a part of them. “I get the most inspired when I see something that’s been carried for more than half of someone’s life,” he says thoughtfully, “Once you carry something for a little while, you establish a connection to it.”

ANNABEL GRAHAM: Can you tell me about how you started making your own leather goods?

MAXIMUM HENRY COHEN: I’ve been making leather goods for... let’s see, five years now. It started when I would make duct tape wallets in the seventh grade and sell them to friends, but I don’t really count that.

GRAHAM: I remember those!

COHEN: I was the kid who would sell them to his friends, I made a lot of them. I stopped when I got a little more interested in film, stop-motion animation, and claymation, and skateboarding and things like that... until I started high school, which was actually a reform school in Montana for two years. I learned how to sew there, I made some pants and things like that, but I also made teddy bears and things to send home to my family. That’s where I really started to feel a little more comfortable with a sewing machine, creating things and turning flat fabrics into objects that had character and life and substance. My first leather wallet was in the summer of 2008. A friend of mine’s girlfriend was planning on donating a pair of leather shorts to Beacon’s Closet but she gave them to me instead, I just cut them up to keep the leather. I couldn’t find a wallet that was simple enough and didn’t have an obtrusive logo in it and I was going through a phase of just not wanting to wear or carry anything with anyone else’s logo because I didn’t feel like it reflected my own character. The only wallets that I could find that didn’t have a logo on them were really high-end, and it felt a little silly to me that the cheaper wallets were the ones that were overdesigned and too big… They were also covered in logos, while the really expensive ones were very simple. That was the premise, kind of my mission statement for my first wallet, to make something that someone could carry that had room to be really broken in and age well.

GRAHAM: Did you make your first wallet for yourself or for someone else?

COHEN: I didn’t even know who it was for while I was making it, or what I was doing for that matter. I ended up giving away my first fifteen or so prototypes. I would carry it for a few days and if I liked it I would give it to a friend, then make myself a new one. I would do that with all different styles for a while. Sometimes I would make one and it would feel too big and clunky, or I would make one that would be too small, and couldn’t even fit money or a Metro card, so it would be pretty useless. Once I established the pattern that I still use today, I started taking it a little more seriously. The internal stitch was a big breakthrough for me. I realized that you could sew something inside out and then turn it outside in and the stitching would be on the inside, that way it won’t tear when you carry it through the years, because the stitches aren’t exposed. That was also exciting for me because I was still learning how to sew leather and I had to work around the fact that I couldn’t sew straight, the internal stitch hid my messy stitching until I learned how to control my sewing machine.

GRAHAM: When you started out, were you just making the wallets out of your home?

COHEN: Yeah, I was making them in my bedroom, with desk scissors, a box cutter and a ruler. There were leather scraps all over my rug, all over my desk, in my trash can, just everywhere, and it was really messy, but really fun and kind of... it felt really natural and homemade, because it was, entirely. In the beginning it was literally with things I found around the house, and I just figured things out as I went along. Then I moved into my living room and I had this little table, this really low table, and I was just hunched over it for what felt like five hours a day, just making all sorts of little things, little tobacco pouches, iPad cases, wallets, all sorts of stuff.

GRAHAM: So you’re from New York.

COHEN: Yeah. I was born on the Upper West Side, and then when I was nine my little brother was born and we moved up to Westchester County. I remember I had never really walked in grass without shoes on before, because I was a city kid, and the whole suburban thing was a big transition. It didn’t really fit that well, I didn’t really enjoy it very much and I missed the city a lot. I moved back at my first opportunity after graduating high school early. I was able to live in Harlem and to work for my dad’s company for a few months, then I started college, and I’ve been back ever since.

GRAHAM: Is there anything in particular that inspires you in your work?

COHEN: I get the most inspired when I see something that’s been carried for more than half of someone’s life. My grandpa’s possessions really amaze me, as well as a few pieces I’ve found at flea markets and garage sales, things that have stood the test of time. Not just because they haven’t fallen apart, but because they haven’t been thrown away. Once you carry something for a while, you establish a connection to it. I’ve always been intrigued by people’s wallets, I found it was an interesting way to connect to people, because most people have a very intimate connection with their wallets. Sometimes there’s kind of a strange story behind how they got it, or a happenstance kind of thing, like, “Oh, I got this because it was seven dollars at a garage sale in Missouri,” or something like that. And then they end up carrying that for fifteen or twenty years, and it transforms into a totally different object with different meanings. I found that a lot of people were just looking for something that was really simple, and there were so many brands that were over designing that I just wanted to make something that is simple and functional.

GRAHAM: It’s interesting, you carry a wallet every day, it’s just this one thing that’s always with you, it almost becomes a part of you.

COHEN: Yeah, and it wears in in different spots, depending on how many cards you have in it, or how much cash you carry, or if you hold on to receipts. It wears differently if you keep it in your front pocket or your back pocket, it’s very personal.

GRAHAM: How did you start making belts?

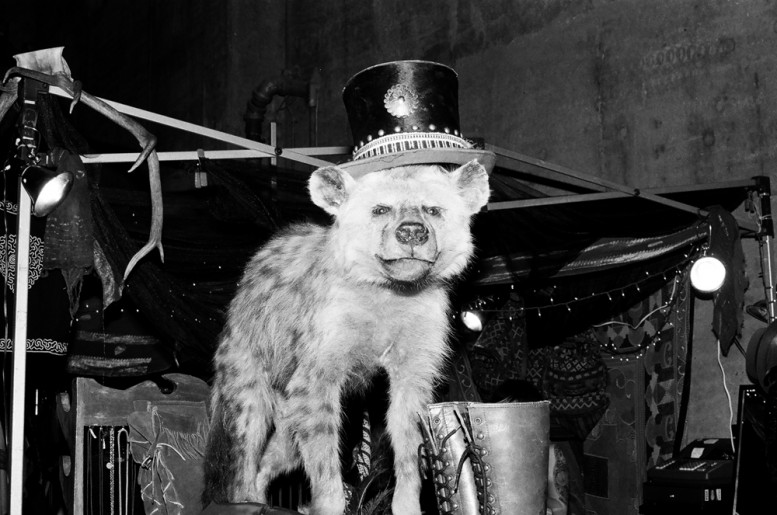

COHEN: It started with the first apprenticeship I did in the fall of 2010. I was working for a guy named Ryan Matthews, who is an oddities collector and leather smith. He collects taxidermy, old medical artifacts and some really beautiful antique lamps. He’s got the most incredible collection of weird stuff I’ve ever seen in my life. He used to do leatherwork for Polo and he would design belts for Double RL and Ralph Lauren vintage collection. He would make these Navajo recreation belts that would sell for something like fifteen thousand dollars at the Ralph Lauren store. He taught me how to dye and edge leather, how to attach buckles and to distress the leather to make belts that looked really old. My next apprenticeship was with this woman named Barbara Shaum, who is, I believe, 87 years old. She has a leather shop on East 4th street between 2nd and 3rd where she makes sandals and belts. It’s a really old-school business, and everything that’s made is made right there, either by her or by someone who works with her. There would be all these guys who would come in saying, “Hey Barbara, it’s time for me to get a new belt, it’s been forty years on this one,” and they would take off this decrepit, old, worn till the very end, belt… something that she had made in the 70s that had lasted 40 years. She taught me how to cut leather from the hide, how to mix dyes to get all different shades, how to attach buckles in a way that they’ll never fall off, and a bunch of other little tricks.

GRAHAM: You’re also interested in film, right?

COHEN: A little bit. My dad works in television and did throughout my entire upbringing, so I grew up visiting his production office on the upper west side all the time, and visiting his friends on sets in LA too. Most of my best friends now are people I met through the SVA film program. I’ve drifted in such a different direction from what they’re doing now, but because we have such different backgrounds, and we spend all day thinking about our specific crafts, we’re able to offer each other advice and insight from different standpoints. My friend Tom just started a production company called Yellow House Pictures, and they’re working on a lot of really cool, exciting projects. I feel like I’m been more in love with written stories than films specifically, just as a form of storytelling. I love reading and I love short stories... historical fiction is my favorite genre. If I were to get back into film I think it’d probably be from a writing standpoint. I dropped out of SVA after one year. I was really turned off because there were all these teenagers who had grown up in the suburbs and were so self-righteous and overly confident, myself included. [LAUGHS] I didn’t feel as though had enough life experience to be a story teller just yet, I was disgusted by how much money I was spending to not be taking school very seriously. I dropped out and started barbacking at a bar in Williamsburg called Hotel Delmano. I was working really hard mentally and physically, I would go home at the end of the day with some money in my pocket, feeling tired and good. It was really fun because while I was working I was also training to become a cocktail bartender. I was promoted to a bartender just after my 20th birthday. I’ve met more people through the bar industry in New York City than through any other social experience of my life. I was fortunate enough to work in three of the best bars in New York over a period of 4 years; Hotel Delmano (in Williamsburg), Elsa and Black Market (both in the East Village).

GRAHAM: All of those bars have a really cool worn-in, vintage-looking aesthetic that sort of matches yours.

COHEN: That’s not by accident. “Objects with character” is sort of a consistent theme... They were all built acknowledging things that have withstood the test of time. A few of the owners of Hotel Delmano are metal workers and furniture designers that make the most beautiful things. They have been and continue to be huge role models for me. I would constantly notice new details about the bar that I had never seen before, like, “Oh my god, I didn’t even see that little chandelier that’s hanging in that corner, or the way that they painted that pipe, how it’s a slightly different color than the wall, or how they distressed the whole room to simulate aging and water damage.” It takes you to a different place. Seeing the way those people have turned making beautiful things into their full-time living is so inspirational, because that’s really all I want to do, is make things that people admire and feel good about.

GRAHAM: You live in Williamsburg now. Having grown up in Manhattan, what’s your feeling about Brooklyn?

COHEN: I’m so happy to be here. It feels like home to me. I’ve made friends with so many people around the neighborhood, from the guy who makes my sandwiches at the deli to the shopkeepers at all of the cool little boutiques around here. I know the buildings so well, and walking down the street I almost always run into someone I know. It has a neighborhood feel that makes me really comfortable. There are so many inspirational small businesses. Sometimes on Sundays I set up a table and sell wallets on the street, which has helped me a lot to see absolute strangers’ gut reactions to what I’ve been working on. After you spend X amount of hours on something, you grow attached to it, almost the way a parent feels about a newborn baby. It takes you out of your bubble. It really helps me to see how differently people react. My products’ quality is a reflection of my level of craftsmanship, even looking at things that I made six months ago makes me shudder sometimes, because my work is constantly evolving.

GRAHAM: Going back to literature and writing, who are some of your favorite authors?

COHEN: I love George Saunders, Denis Johnson. I would say E.L. Doctorow is my favorite author, and Ragtime is my favorite book. It’s set at the turn of the century, and it covers both fictionally and non-fictionally what was going on during that time period, which is my favorite type of book. Before that, I read The Cider House Rules, which I really enjoyed, but my friends would make fun of me for it, ‘cause I guess it’s kind of a girly story. [LAUGHS] I also like some more spiritual pieces, Siddhartha is really beautiful and influential, about how one can live with absolutely nothing. The Prophet, by Kahlil Gibran, has been a staple in my life. I wouldn’t consider myself religious in any way, shape or form, but I do try to stay in tune with my own integrity and karma, and that was a guiding light for me in my late teens. My ideal day would be cooking my own breakfast, riding my bicycle to the studio, working and making things all day, hopefully meeting with some clients who are really excited about the products I’m making, eating a delicious dinner at one of the amazing places in the neighborhood then going to bed to do it all over again the next day. That’s pretty much it.

GRAHAM: The books you named and even your ideal day all seem to go along with this theme of almost simple, Spartan existence—making things yourself and existing without all the “noise.”

COHEN: We’re living in the information era and there’s just so much everywhere, and it can be really overwhelming. To take a step outside of what’s going on and to look at what you connect with and why you connect with it... I don’t think you connect with things for the reasons you think you do right off the bat, there’s usually something underneath it. That’s what I strive for in my work, to make things that look upon first glance like something that’s almost normal, but then once you wear it and once it becomes a part of you, you fall in love with it. It has a much longer life span then something that is flashy and will end up falling apart one day.

GRAHAM: And the more you study one of your wallets, the more little details you notice.

COHEN: I tried to design them to be as simple as possible. I try to leave room for character to be developed, to just lay the foundation and then the rest is up to whoever wants to carry it. I have friends who have drawn on the insides of their wallets with Sharpies and things like that, and it’s the coolest thing because they’re taking something that I made and just transforming it into something that is theirs. I did start putting my brand on the on the inside of the wallets, but they are also available without them. I don’t want to throw my image in anyone’s face, you know, if they want it, they can have it and adapt it to their own style. The original concept for things without logos came from Hotel Delmano, which is really inspiring. They don’t even have a sign outside, they don’t have a business card, they don’t have coffee to go with their logo on the cup. There is no logo for Hotel Delmano. You can seek it out and go there, but you can’t take any of it out with you. That’s why people keep coming back, it’s because their product and experience stands on its own, not a commercial piece of branding. My favorite client is someone who has been referred by someone else who already has a piece and really appreciates it. I’d rather have those people tell their friends, or get them for their friends, instead of having advertising to bring in customers.

GRAHAM: So you don’t want your face on a park bench anytime soon? [LAUGHS]

COHEN: [LAUGHS] No, definitely not. That’s kind of the wrong idea... At least for right now.

GRAHAM: What’s your goal for the future?

COHEN: I’ve been in a developmental stage for a really long time, making different prototypes and styles and colors, and I would really like to go into production mode and be able to make ten times what I’ve been making in the past, and expand to make new products... eventually even a clothing line. For the time being, I’m just focusing on nailing down my craft and making some things that feel like they can be taken through anything. I’ve been working on some guitar straps and some small bags. I’m also looking for retail stores outside of New York to carry my pieces. I’d really like to see the wallets around the world, in France and London and Italy and Australia. It feels really local right now. I’ve already gotten them in pretty much all of my friend’s pockets, so I’d like to start moving on to other likeminded people that I don’t know just yet. I’m also really excited about a couple projects I’m working on with my friends that are using their skill sets and combining them with the things I’ve been working on. I just shot a look book with my friend Dave, and my friend Alex is putting it together in a little printed book that I can pass around to friends and shops around the world. Basically, this craft is so exciting for me because it’s given me the excuse to base a profession around the things that I like doing and the people I like interacting with. And to me, that’s what it’s all about—work that doesn’t feel like work. I look forward to coming to my studio in the morning, which is a sign of moving in the right direction.

GRAHAM: If you could be anywhere in the world right now other than New York, where would you be?

COHEN: There’s this lagoon in Jamaica called the Blue Lagoon, which is fresh water that comes from the center of the earth, so they say, and it tastes amazing. Swimming there is one of my ideas of paradise. It’s pretty easy to think about being other places when it’s wintertime in New York. [LAUGHS] But whenever I leave New York, I find myself missing it after just a few days. I guess it’s another implication that I’m going in the right direction, missing my home when I’m on vacation.

GRAHAM: Is there a way in which living in New York City and growing up here has inspired or affected your aesthetic?

COHEN: Most people that live in other parts of the world travel everywhere they go in a car that allows them to just throw things everywhere, and they have more space than they know what to do with. Living in New York City on a budget has taught me to be extremely compact and intentional about the things I carry with me, the things I keep in my home. A lot of people’s wallets are bigger than they need to be, because they’re carrying things that they don’t even remember they have in there. It’s essentially baggage from the past that’s unnecessary and weighs you down. Because my wallet design is smaller than the standard one, it almost forces people to downsize, to simplify their lives. There’s a lot of baggage that we just carry around with us out of habit. It’s pretty important to have a streamlined existence [in New York], because extra things just drag here, and that’s why I like the “no frills” design policy.

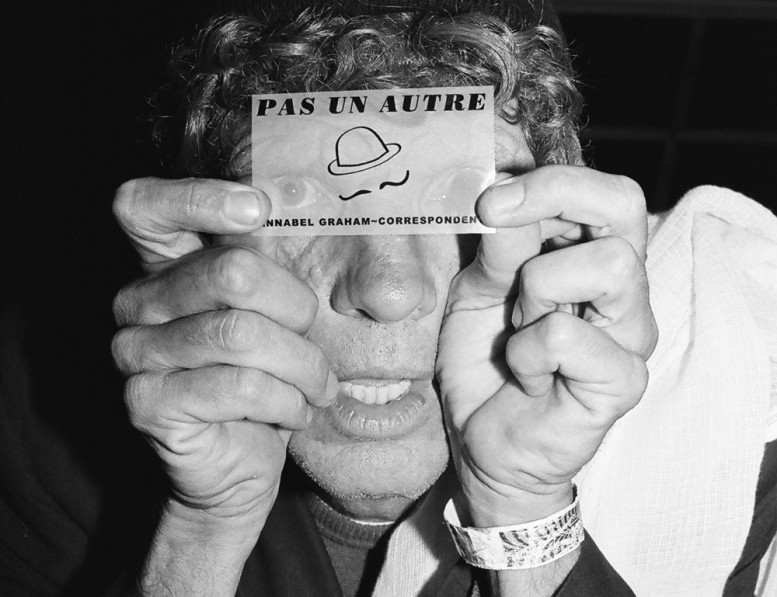

Text and photography by Annabel Graham for Pas Un Autre. Visit the Maximum Henry website to view more.