interview KATJA HORVAT

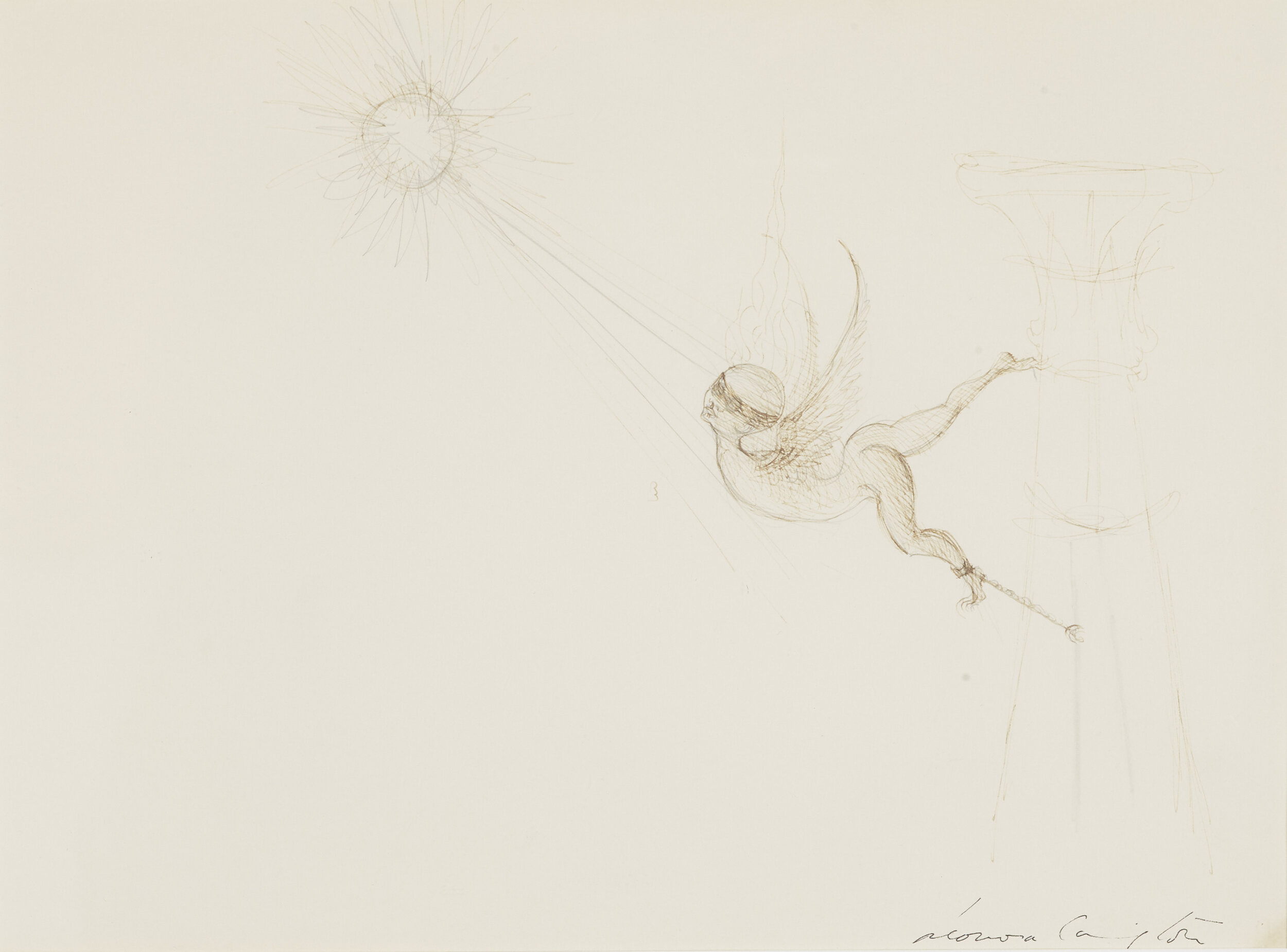

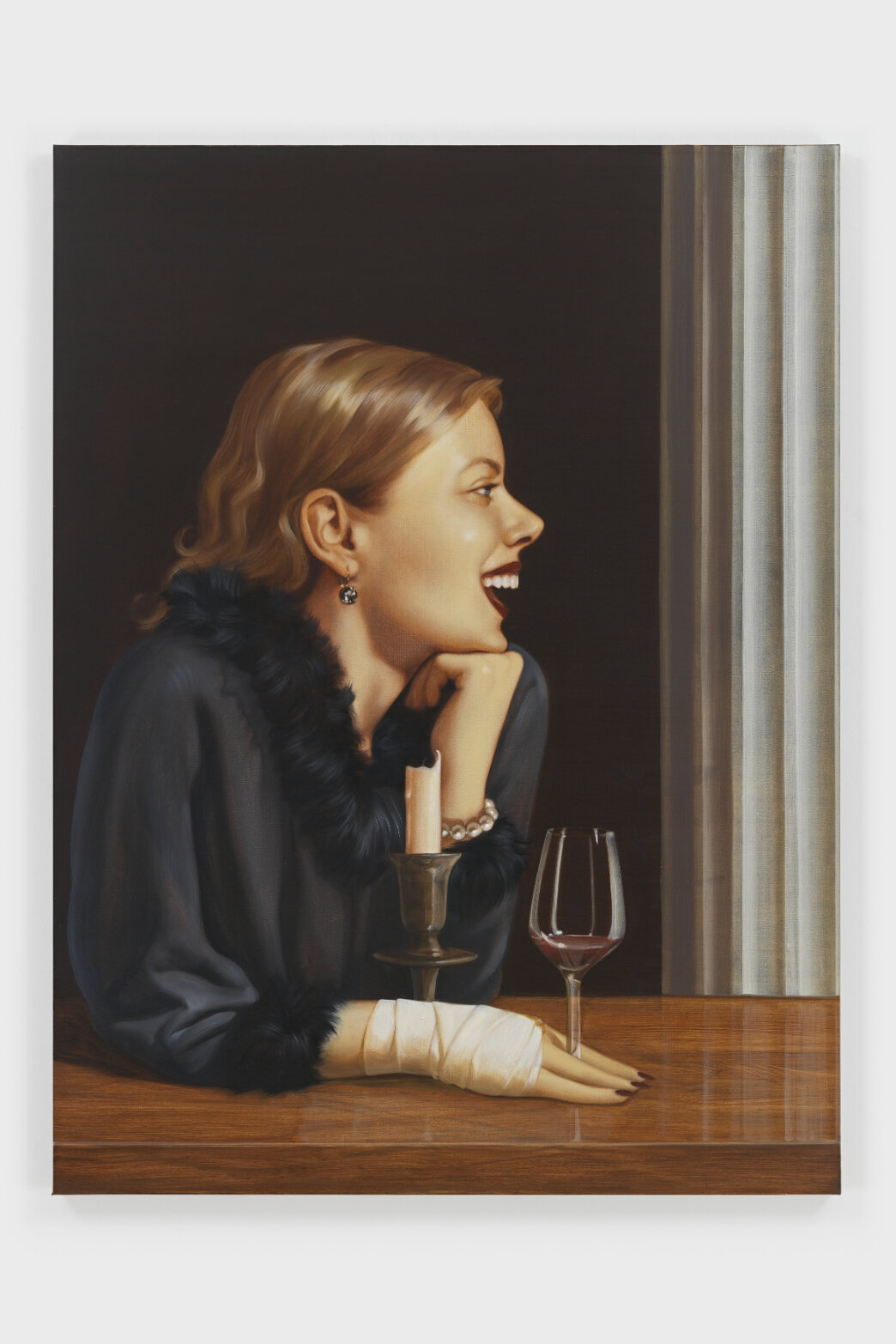

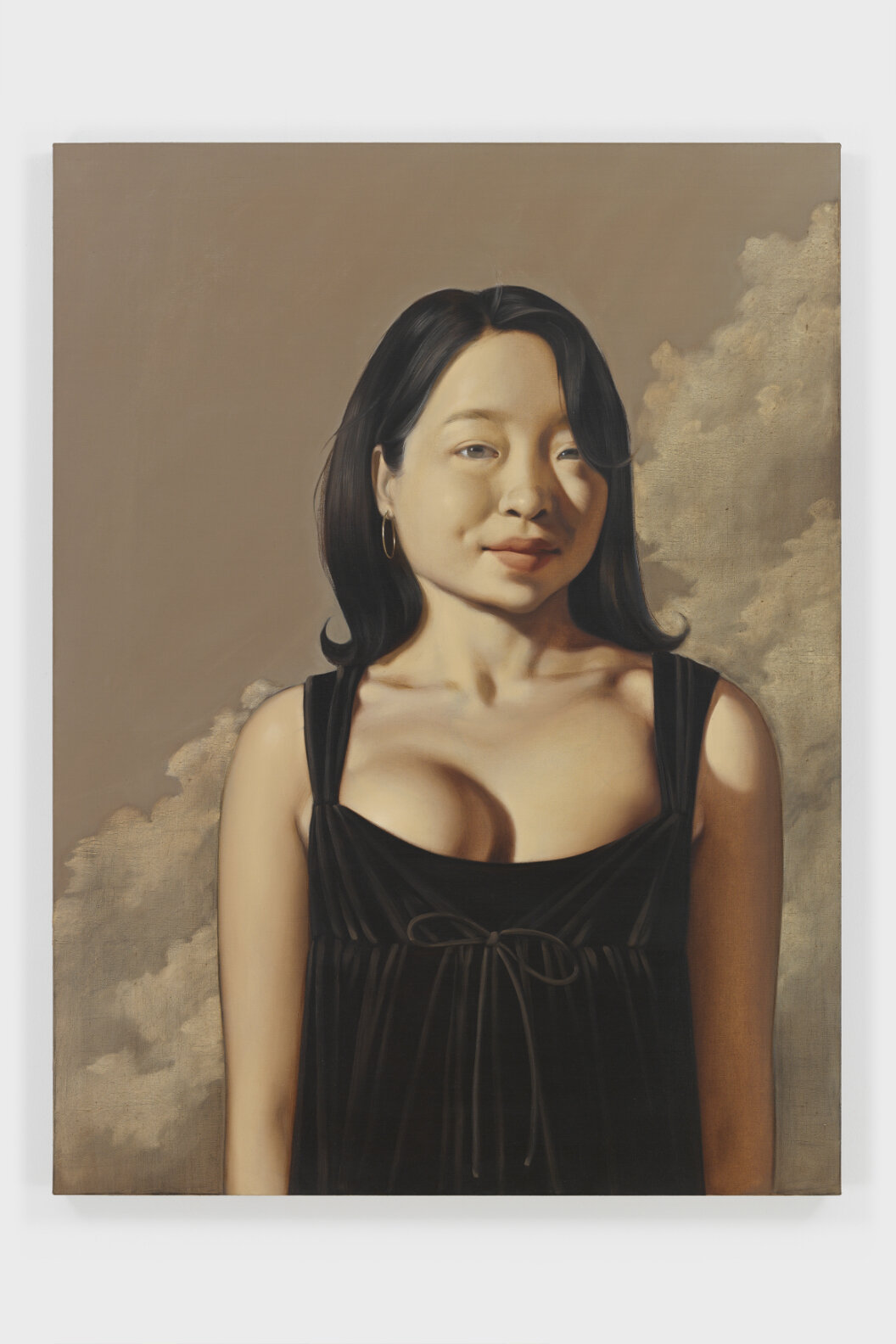

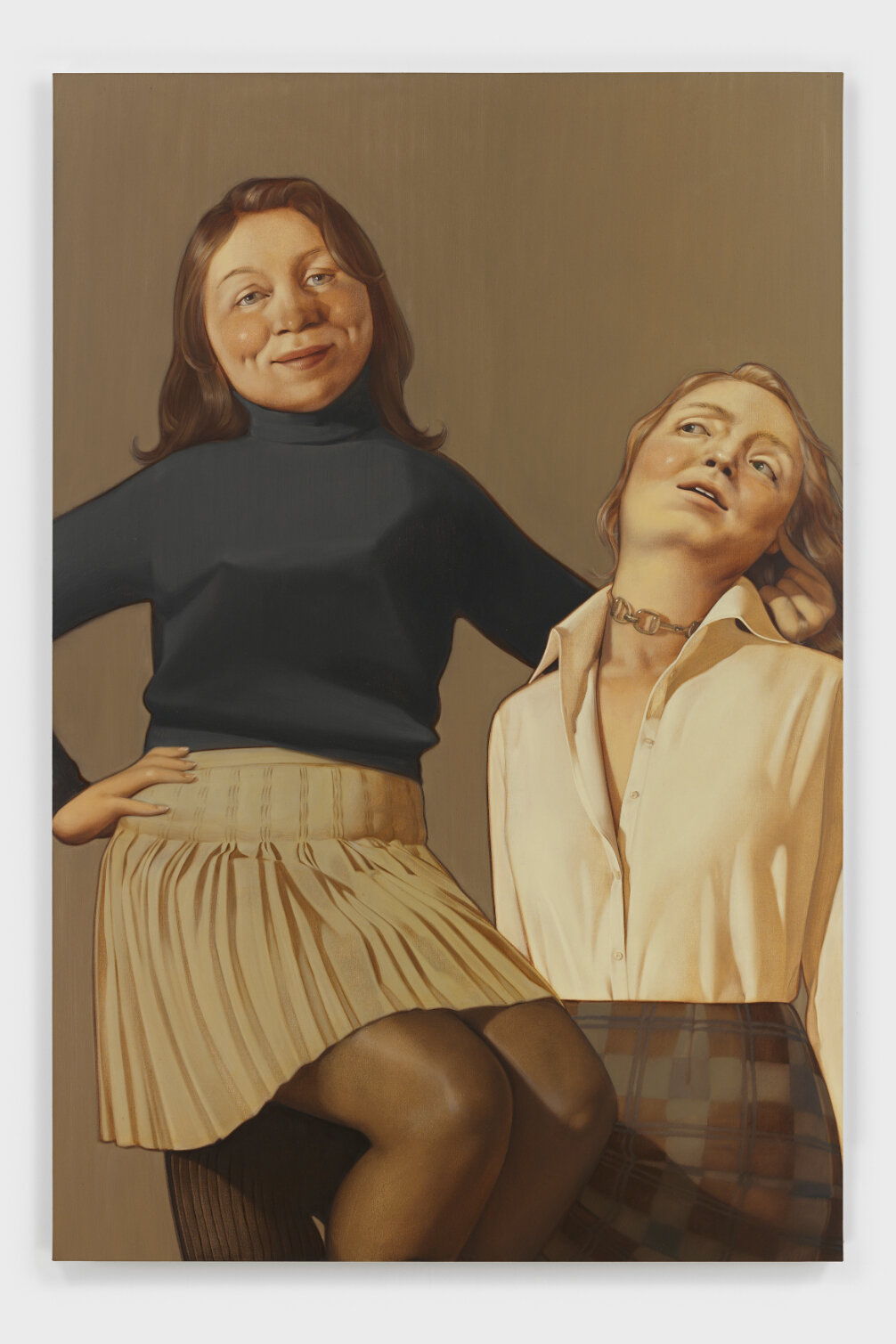

images courtesy AKEEM SMITH

originally published in Autre’s Doppelgänger Issue (Spring 2021)

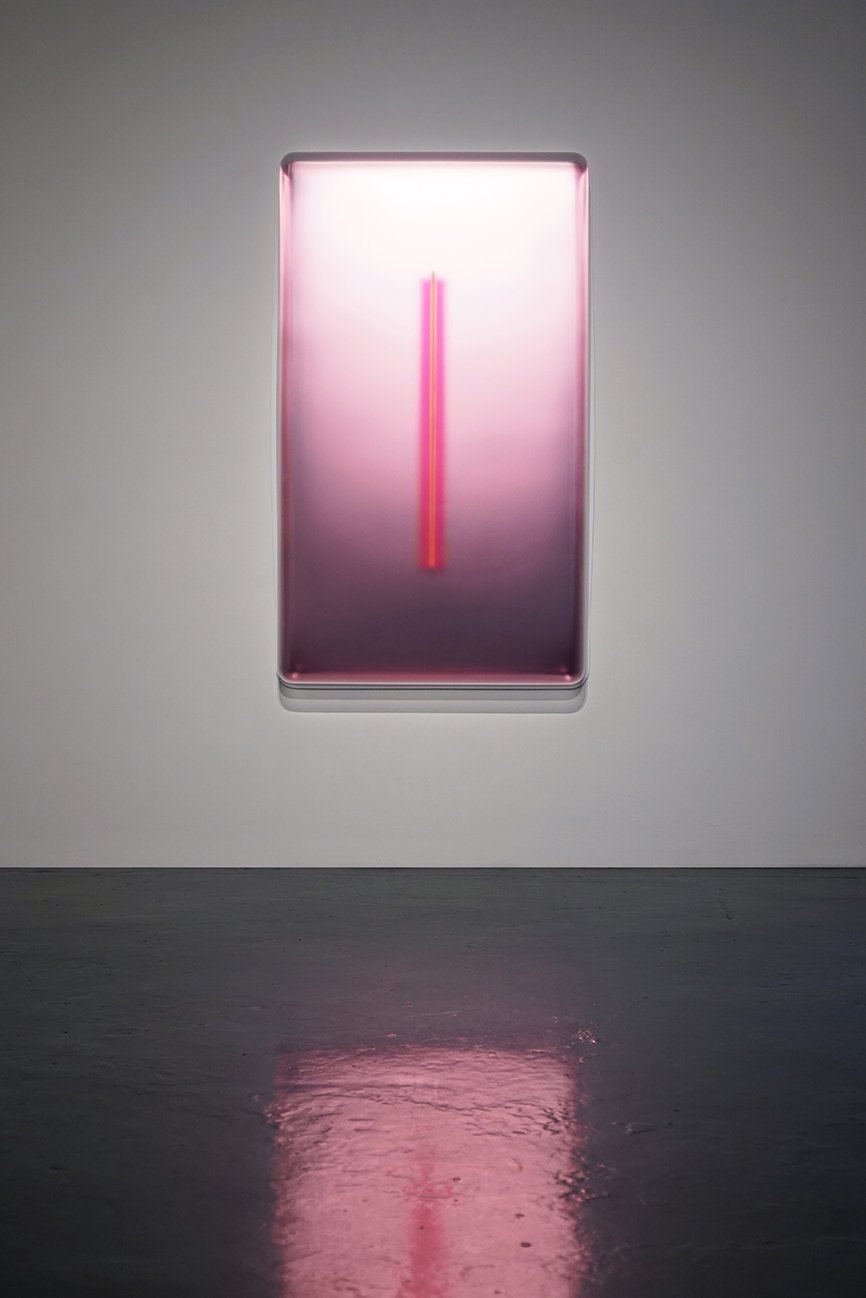

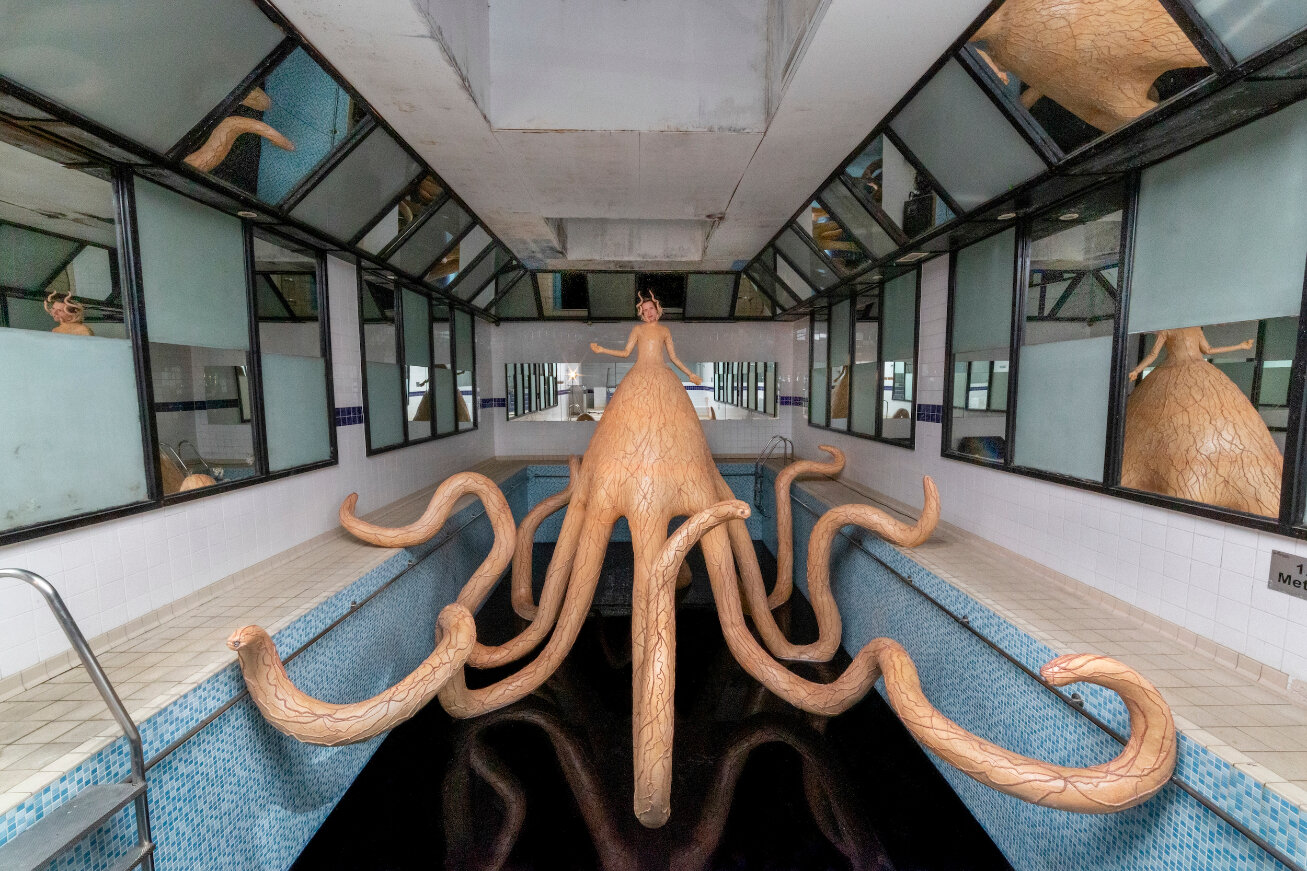

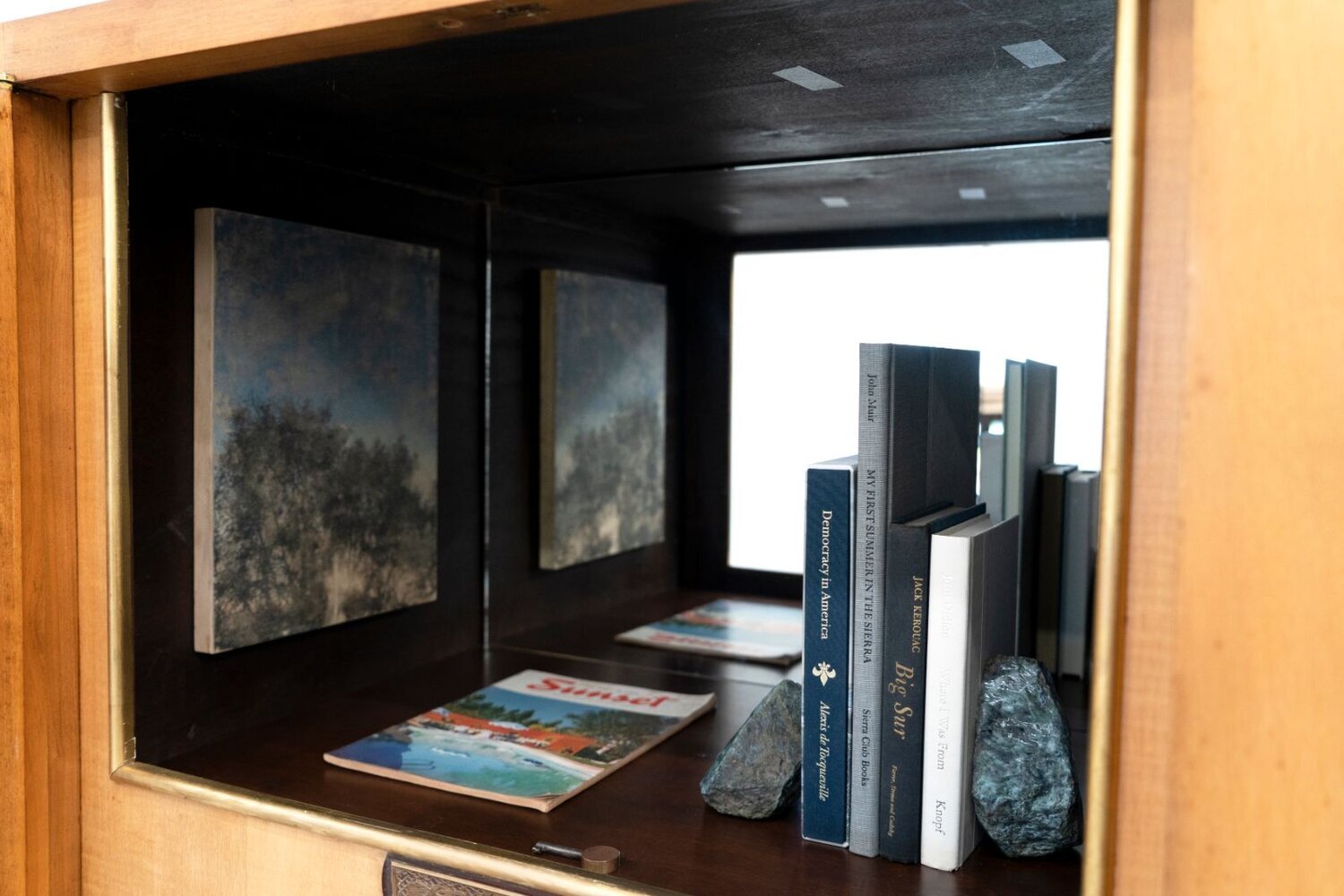

Akeem Smith maintains a pivotal role in preserving and archiving the visual aspect of dancehall culture. Smith, a Kingston-born, New York-based stylist, designer, consultant, and artist, is the scion, godson, and nephew of Paula Ouch, founder of House of Ouch—one of the most infamous and respected designers inside and outside the dancehall community. Smith started researching and documenting the depths of dancehall roughly fifteen years ago. His interest is primarily the role of women within the culture, and how their contributions stand at the very center of the movement’s legacy. Compiling a vast selection of images, combining documentary footage, found footage, flyers, garments, architectural artifacts, Smith created No Gyal Can Test, an ongoing project of exhibitions, installations, sculpture, photography and videos that unite his observations. They explore past and present representations of the community, issues of racism, political oppression, and gender identity. Smith often says this show/research project is made for the future; for other generations to tap into the legacy of dancehall. Akeem Smith's first European solo show, Queens Street opens November 18th, 2021 at Heidi, Kurfürstenstraße 145, Berlin.

KATJA HORVAT: Let’s just go in right away. My first recollection of "No Gyal Can Test" goes way back to 2012, I can't fully remember what it was, was it a party? But I do know Shayne [Oliver, founder and creative director of Hood By Air] DJed.

AKEEM SMITH: It was Shayne, yes, and Venus X, and DJ Physical Therapy. That was my first and only fundraiser. I just needed some money to go to Jamaica and start collecting the materials.

HORVAT: Buy your way in!

SMITH: Jamaica is very economically driven. Even though I didn't make that much money that time, I made enough, and I wanted the people to see the value in their archive—that I wasn't trying to swindle them, and that I thought what they had and their story was worth a lot. On the Island, they're constantly reminded that dancehall is sort of this negative thing.

HORVAT: Even after all these years?

SMITH: Even after all these years, for sure. A hundred thousand percent, even more now, to be honest.

HORVAT: It’s insane that it has had such an indelible influence on music and culture at large, but where it actually comes from, its legacy goes unappreciated.

SMITH: I think dancehall has given the country a lot of cultural currency that's allowed them to be respected globally—other than the Olympics. It's just a shame that it's still seen as a negative thing, but in my art and practice it is not my mission to sway anyone’s points of view.

HORVAT: Do you think religion and let’s say some socially “acceptable” norms have anything to do with it?

SMITH: Yes and no. Dancehall is a nocturnal economy, so it's become a scapegoat for certain arguments.

HORVAT: Portrayal of women is also a sensitive topic when it comes to dancehall—not necessarily on the ground but more so when it comes to what others think of it: a whole degrading debacle.

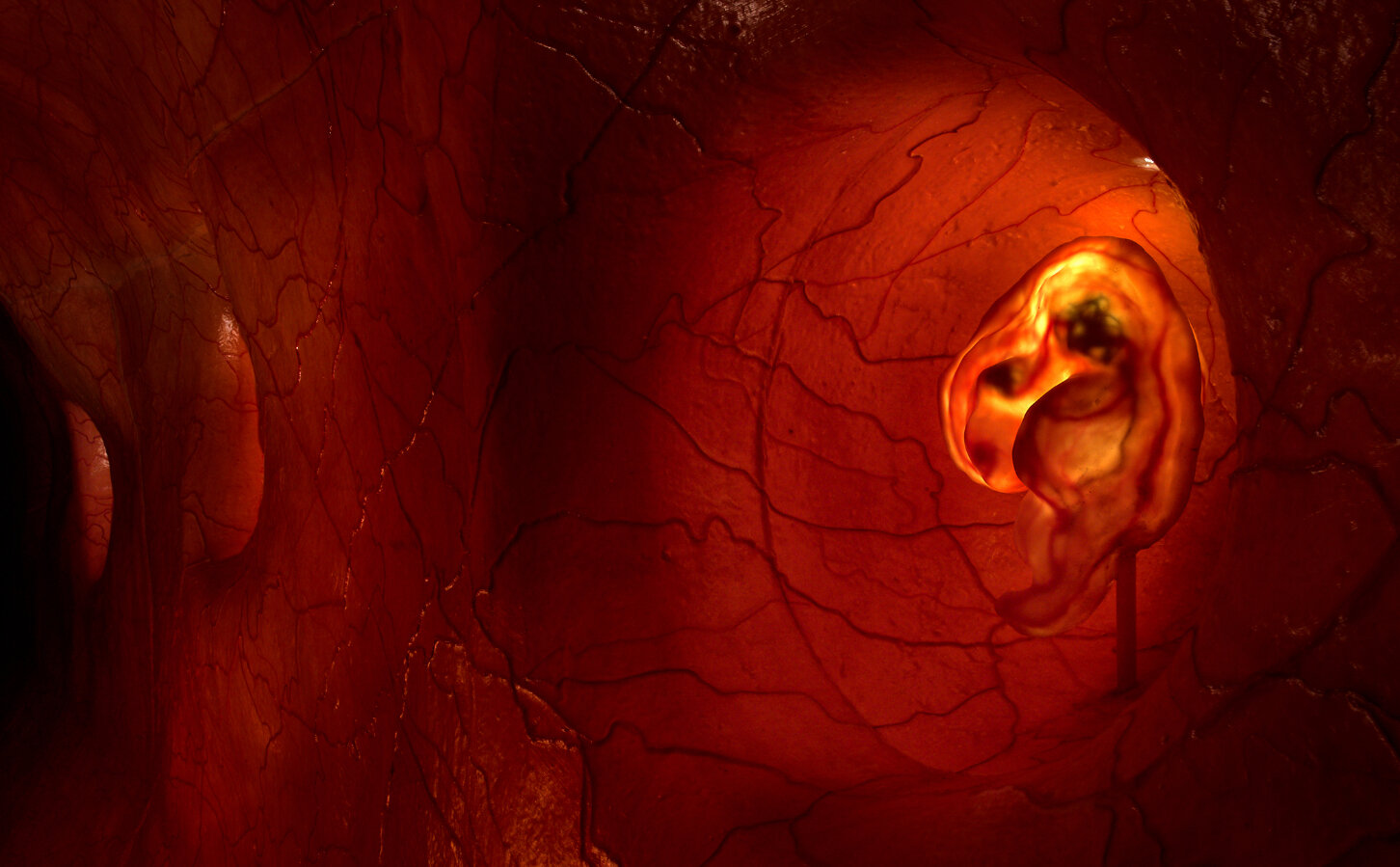

SMITH: Globalization is a thing, and some site specific culture customs aren't for everyone. I think it's super relative. People on the outside make assumptions. I see the dancehall space as this primal space, equivalent to nature, some behaviors are a mating call. The video piece in Soursop honors that. The women in the videos are performing acts, self-caressing; they are appreciating their bodies.

HORVAT: You've been working on this project for fifteen years now? Has researching dancehall, the women in it, fashion, etc., influenced the way you work as a stylist and a designer?

SMITH: I've never tried to bring dancehall to fashion or anything like that, so no.

HORVAT: Okay, a lot has been written about where the name [of the show] comes from, but I want to know why you even went with it in the first place?

SMITH: The name/saying was written behind a photo that my dad had. It was just a normal photo of one of his ex-lovers sitting in her bed. As to why this name, it was not even my idea to go with it, to be honest, it was Shayne’s, and this goes back to 2009. I liked No Gyal Can Test, but I wasn't confident in it. And he was like, Oh my god girl, you should just name it this, it's like already here. My motto, though, has always been to not look too hard for inspiration. I think it's always right in front of you. I don't feel you have to dig too hard to be inspired.

HORVAT: A big thread through No Gyal is House of Ouch. You grew up with them, Paula [Ouch] is your aunt and godmother, did their/her world shape yours?

SMITH: Not in a way you would think. What did shape me was how they came up with ideas. When I was a kid, I really wanted to be a broadcaster. Dancehall, for me at that time, I thought it was cool, but I never thought it was something I wanted to do. With some dancehall people, you would see them and they would look like a million bucks at a party, and then you see them like two days later, you wouldn't believe that it's that same person. So, it always felt like a mirage, and I wanted something more, something that felt like real wealth.

HORVAT: That reminds me of drag balls; the ball fit versus real life.

SMITH: I guess you can draw the comparison but I would compare it more to RuPaul's Drag Race. And I'm talking about men and women. They made such an effort. I think it had a countereffect on me, because now I want to look like a bum, but a bum with money. That's how dancehall affected me, it shaped my taste but not my world. It also shaped how I view women.

HORVAT: Has it shaped how you dress women?

SMITH: No. When I do styling work, I think, what would I dress like if I looked like you. That's more of how I like to approach styling. Like, what would I wear if I had your body?

HORVAT: So, to go back to dancehall. Who was more celebrated in this on the ground, men or women? Because through the research that I was doing, I could find a bunch of stuff on people like Bogle or Colo Colo but not so much on women specifically. I mean, there are Queens like Carlene or Patra, Lady Saw, etc., but the representation just somehow lingers more on the man's side.

SMITH: I don't know the exact answer for that but I assume that it's just so patriarchal here. I think men acted more as the spokesperson for dancehall back then, but maybe that's going to change. Let's see.

HORVAT: You think there's still time?

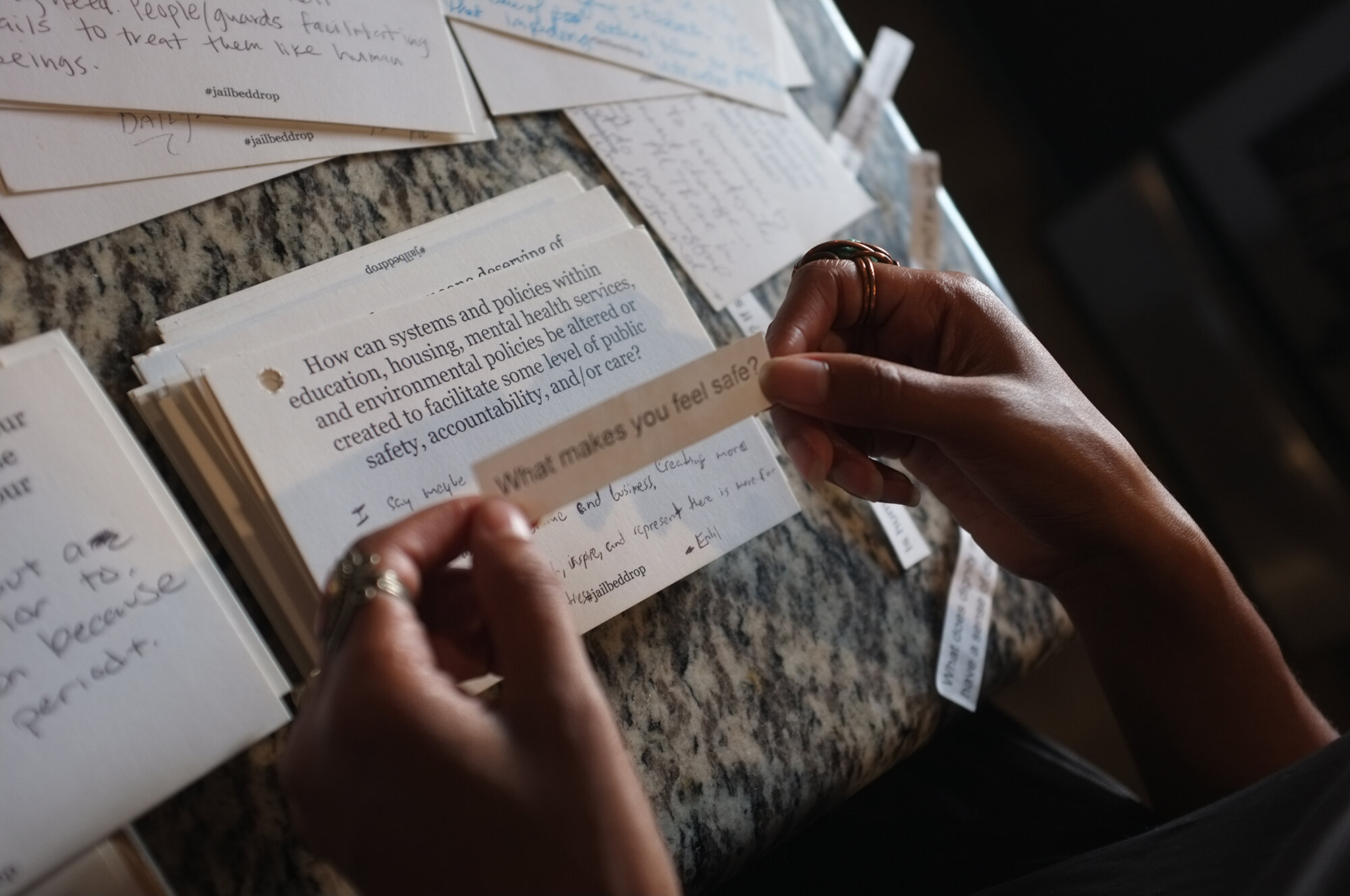

SMITH: Well maybe, a lot of the men that used to party in dancehall in the era that I highlight have transitioned [died]. Maybe something changes as far as knowing who was giving these unknown subjects of Black history a space. Whenever there's an opportunity for the dancehall patrons to speak, I give them that opportunity—to talk about how they feel, to be seen. I’d rather continue having them be a part of the speaking engagements.

HORVAT: Everything is always better when it comes from the source.

SMITH: Exactly. It's better if it comes from them, rather than me saying how this is affecting me, or them, or whoever that may be. And I'm also not the dancehall academia like that—I like the anthropological part most.

HORVAT: What about the whole anthropological system of it interests you the most?

SMITH: You know, we always look at old pictures, especially working as a design consultant/stylist. You're always researching images of people, places, things and a part of the job is world-building, so our imaginations run wild. There aren't a lot of first-person narratives when it comes to Black history and that is really important to me. It is about direct representation, not a representation of a representation.

HORVAT: It can get tricky, though, as you don't always have the privilege to access the source. So, when it comes to that, you are holding onto a narrative that comes from some other narrative. I studied cultural anthropology and there were moments when I wanted to cover something, but I felt like an imposter, as it was not my story to tell, or even touch sometimes.

SMITH: I get that, but you also gotta let it go. I don't mind looking like an imposter. With the dancehall stuff, people have wondered how I've gotten all this stuff and information; people have indirectly asked me if I'm code switching, it's been really funny. In translation, some think I'm acting straight, because dancehall is so homophobic, to acquire things...But I would never, ever do that.

HORVAT: Homophobia and the macho perception in dancehall, dominance, what males should be, etc., is a whole other conversation. One would think things would change over time, but no.

SMITH: Nothing has really changed. It is all so deeply rooted in the political system. It is not just that, though. Dancehall is also used profoundly as an excuse for any violence happening. With COVID right now, in Jamaica—there's been more than a hundred murders since January this year—and they don't have dancehall to blame it on, as there are no events obviously.

HORVAT: In the ‘90’s your godmother [Paula Ouch], also moved to NYC because of all the violence and looting she experienced, right!?

SMITH: Correct. Basically, the mafia started to tax their business. If you want to continue operating your business in Jamaica, you need to pay for your own protection.

HORVAT: Was that post or pre-Belly (1998)?

SMITH: Pre-Belly.

HORVAT: And then for Belly, she came back to Jamaica. What was her role exactly?

SMITH: She played Chiquita, who was an assassin.

HORVAT: So apart from fashion being pivotal in No Gyal Can Test through Ouch, you also brought a fresh element in collaboration with Grace Wales Bonner. You guys worked on the uniforms for the staff. How did that come about?

SMITH: With Grace, we always wanted to do something together, but there was never a right moment until now. Apart from her being absolutely right for this collaboration on its own, she is also personally connected to Jamaica; her mom is English and her dad is Jamaican. So her trajectory and story are a big part of the investigation into the Caribbean diaspora that's taking place inside No Gyal, not her family specifically, but many like it.

HORVAT: There are a lot of moving parts to this show and everything is very well rounded. From the uniforms with Grace, to the mannequin collaboration with Jessi Reaves, to the mock-up housing that was built from the stuff you collected on the island. That said, the videos are really central.

SMITH: The two main videos are, Social Cohesiveness and Memory. Then there was the Reconstruction Act, that's embedded in the sculpture, and then there is Influenza. Then, one was called Queen Street…

HORVAT: Is the latter the one that feels like a dream?

SMITH Queen Street documents the first fashion show that I went to—it was my family's fashion show. The way it’s edited is sort of how I remember it. It's one of my first memories. So, it's a little bit hazy, and yes, can feel like a dream. You know, memory in general is something very weird because I feel like half of it is what actually happened and then the other half is made up in your head, and I mean that in regards to just about anything, not just this show.

HORVAT Walk me through the editing process.

SMITH To be completely honest, editing came from the curatorial team. I am the maker, that said, there were elements I specifically wanted to highlight, to show the duality of the dancehall world. I wanted to accentuate, to some extent, how the Eurocentric version of beauty is still very much present and is so specifically dancehall; the blonde hair, the blue contacts…. So I was more on that, but the show was brought together and mapped out by curators.

HORVAT So one show is behind you, one is about to open. To think about the story you are trying to tell, what is one thing you want people to get out of it?

SMITH I hope they can somehow connect what they are seeing to something in their lives. You don't have to come from this world to connect or feel things. I would love for people to see value in something that maybe they didn't deem as valuable before.

HORVAT I think you are onto something. It’s definitely not the type of show that leaves you dry. Anyhow, if you could pick one song that would serve as the soundtrack to your life, which one would it be?

SMITH Oh, Peaches "Fuck The Pain Away."

HORVAT If you could be any character from a film or a TV series, which one would you be?

SMITH I think Scooby Doo because he never actually spoke. He hasn't said a word yet he is still such an icon.

HORVAT He's a mute protagonist. [laughs]

SMITH Doesn't say a word yet he leads it all. Everyone seems to like this character for a reason they don't actually know. And I see myself in that way. I think people like me for reasons they don't even know.

HORVAT If you could only watch one movie for the rest of your life, which one would it be?

SMITH If I could just continue watching dancehall parties from the ‘70s to now, that would be good.

HORVAT What's your favorite memory as a child from Jamaica?

SMITH In my family, we're all part of different socioeconomic pockets, and I used to love being in the ghetto because that's where all the excitement was. There was always something going on. You never had a moment to yourself, but I loved that. I miss when that didn't bother me. Now, it kind of does, but there was a point in time when all the drama was fun.

HORVAT What's your favorite memory from New York?

SMITH I haven't had it yet. It's coming.

HORVAT What do you want to be twenty years from now? Where do you see yourself?

SMITH Hopefully just healthy and still working.

HORVAT Do you want to live in Jamaica, New York, or do you see yourself somewhere else?

SMITH No, hell no. I don't know where I'm going to live, but hopefully I'm not bound to a place.

HORVAT What's your favorite flavor?

SMITH I like Great Nut Ice Cream.

HORVAT What's your favorite song from Lee "Scratch" Perry?

SMITH Anything that he claims Bob Marley has ripped off.

HORVAT What do you fear?

SMITH I fear being older, and reminiscing, and regretting not having as much fun as I would like.

HORVAT Where do you get your energy for work and for life?

SMITH Reality television.

HORVAT What's the best life advice that someone has ever given to you?

SMITH I don't know—keep on going. Don't stop.

HORVAT Do you ever want to retire?

SMITH No, I'm going to be like Cicely Tyson for sure. Like a thousand percent. She died three or four days after she did the Kelly Ripa interview. Still dolled up. Two weeks prior she was on set filming something. Yeah, that's my hope. Oh, I guess my goal is also to not be jaded.

Katja Horvat: Are you scared of that?

SMITH Yeah, I'm scared of being jaded. I don't think I'm gonna be, though because I make an effort to not be.

originally published in Autre’s Doppelgänger (Spring 2021) with an accompanying conversation between Akeem Smith and Lee “Scratch” Perry. Purchase here. Akeem Smith “Queen Street” opens at Heidi Gallery in Berlin on November 18.