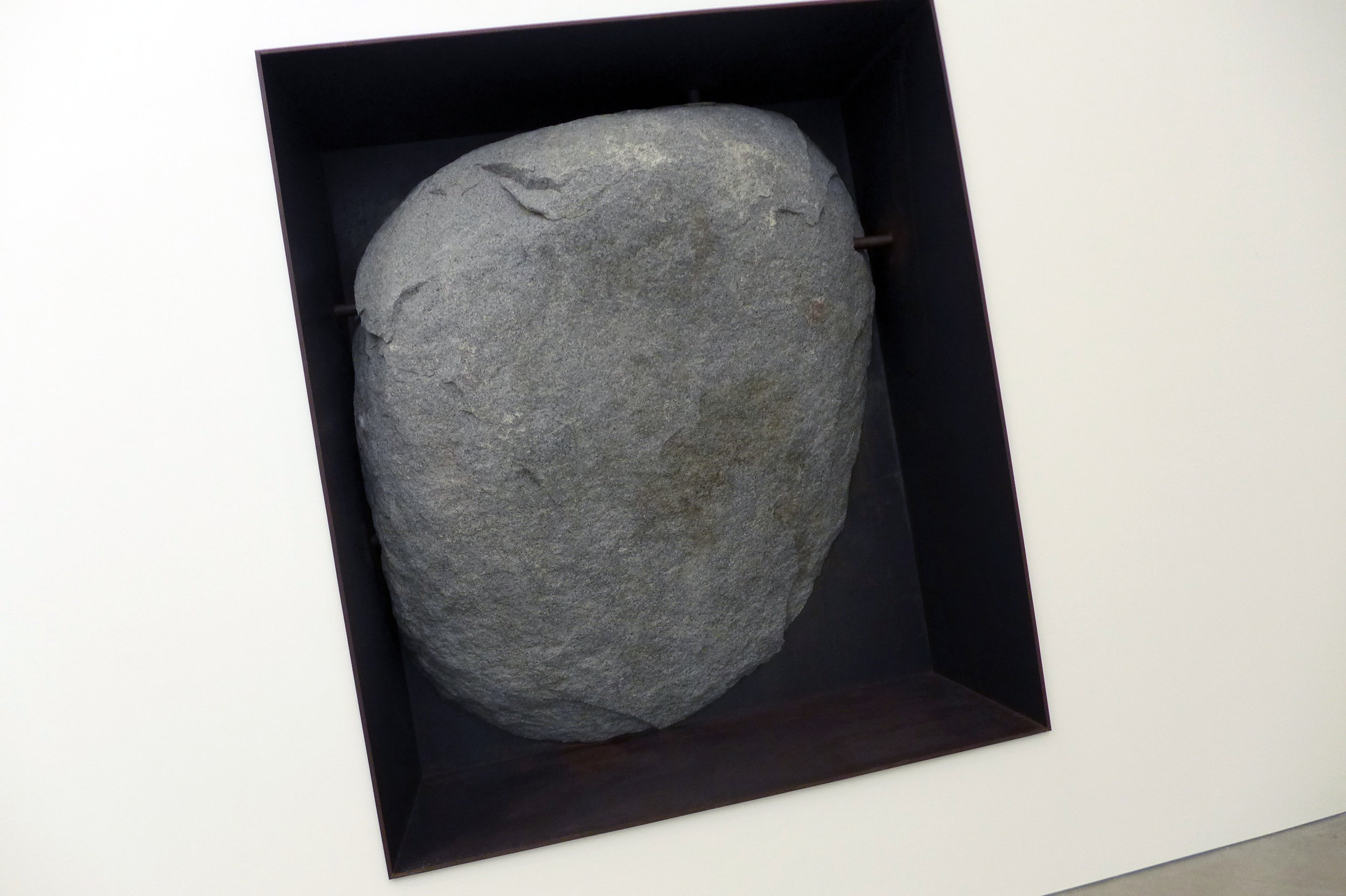

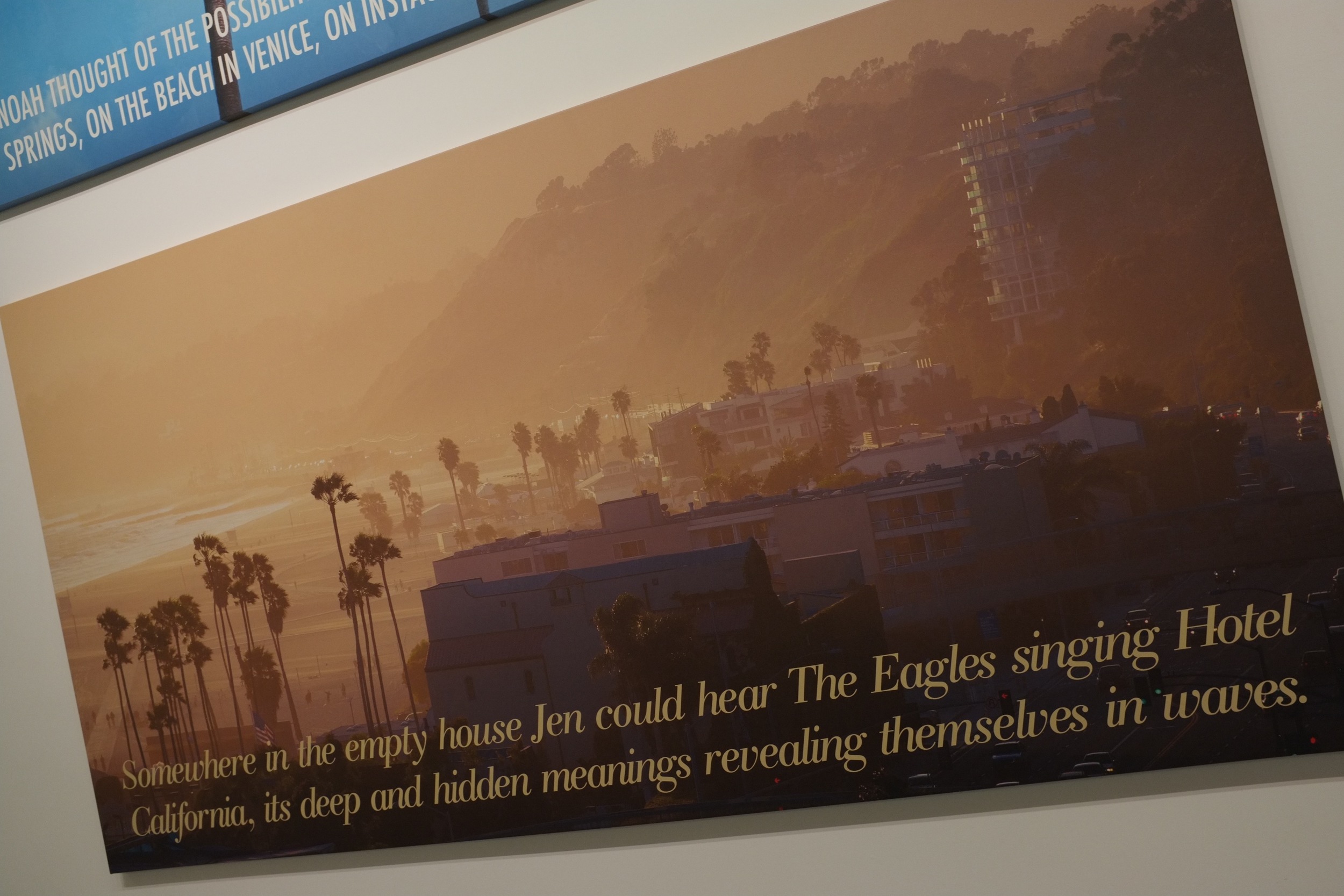

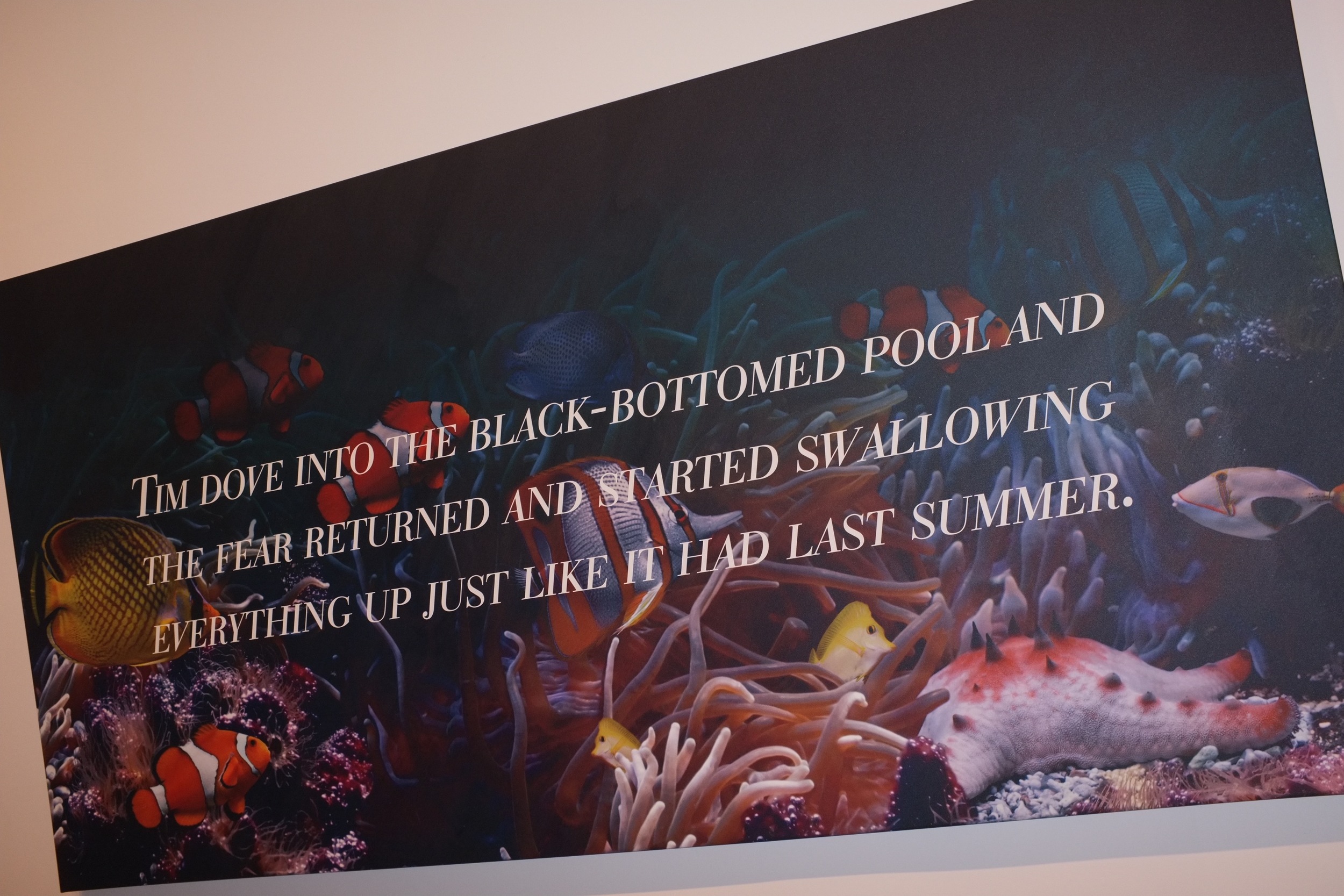

NAN GOLDIN

Gold, 2016

Archival pigment print, in frame

60 1/4 x 116 1/4 x 2 1/2 inches (153 x 295.3 x 6.4 cm)

Ed. 1/3

© Nan Goldin

Courtesy the artist and Gagosian

text by Jennifer Pjieko

“It’s a lot of work, but I’m free now. I’m free!” Artist ektor garcia gestures to the logo on the T-shirt he’s wearing—a black staffer shirt with FRIEZE spelled out in white letters across the middle. garcia had taken some artistic liberty with the art fair-and magazine-branded top, blacking out the letters I and Z with marker, leaving only FREE legible.

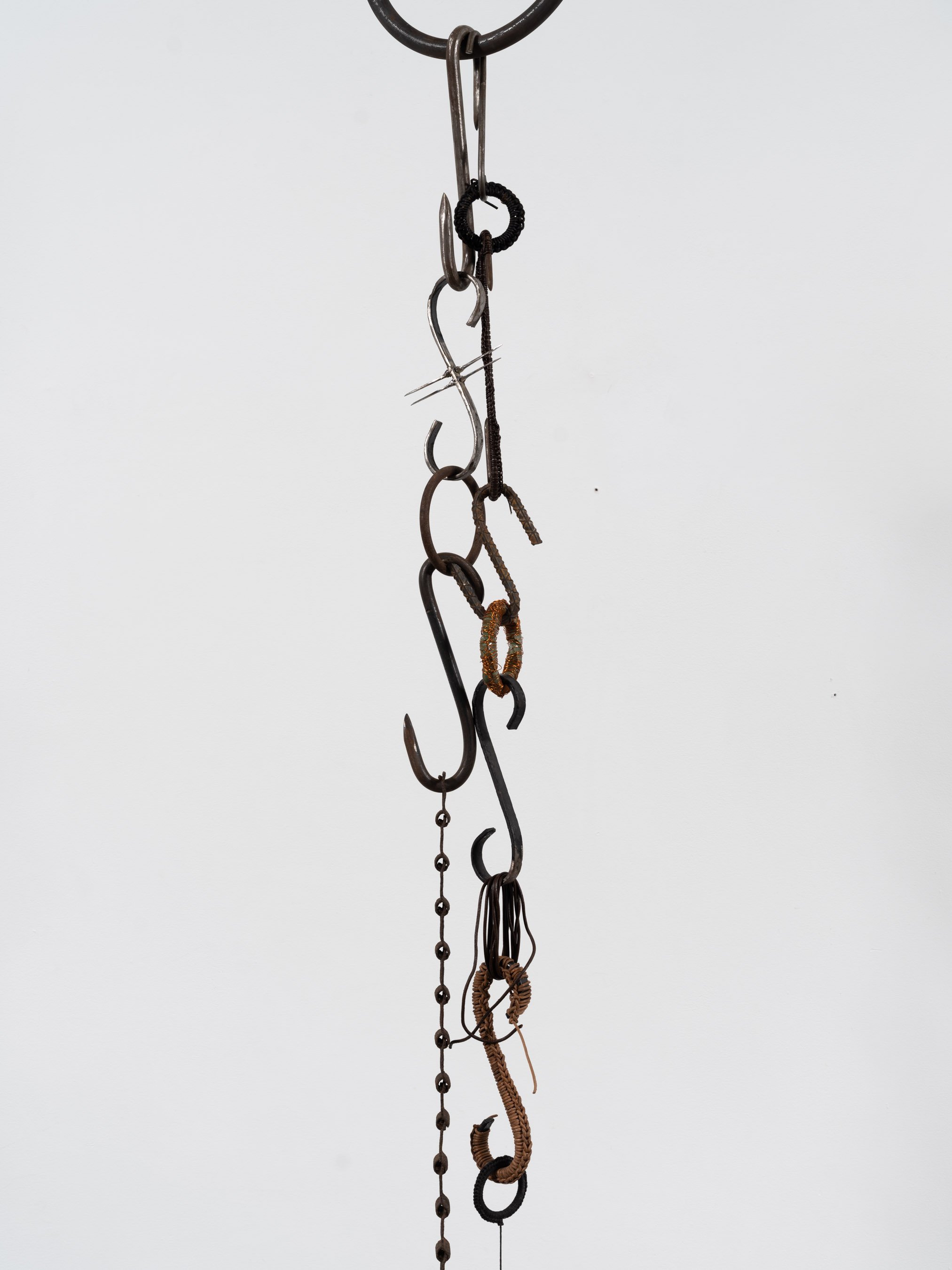

ektor garcia, cadenas perpetuas, 2023 (detail)

Welded steel, hand bent, handmade steel hooks, found metal, glazed ceramic with copper wire, horseshoe nails, and crochet leather.

Dimensions variable.

We were standing around inside Cedric’s, the top-floor café of Frieze New York, underneath garcia’s installation la llorona, a hanging mobile of mixed-metal woven teardrops that illustrated the indigenous Mexican mythical figure of La Llorona: The “weeping woman” drowned her hungry children after their father, a wealthy Spanish man, abandoned the family, and she sheds tears of mourning for them for eternity. Here, as part of Frieze’s curated program, her shimmering, coppery chains gathered into teardrops evade the heavy, matte black net that is there to catch them and float over us as we get together for cocktail hour (we’re not sure which one we are part of at that moment; the restaurant, like Day 1 of any VIP preview day of an art fair, hosts a cluster of many overlapping celebrations at once, bringing cheers and the pop of champagne bottles to crowds from opening to closing hours.

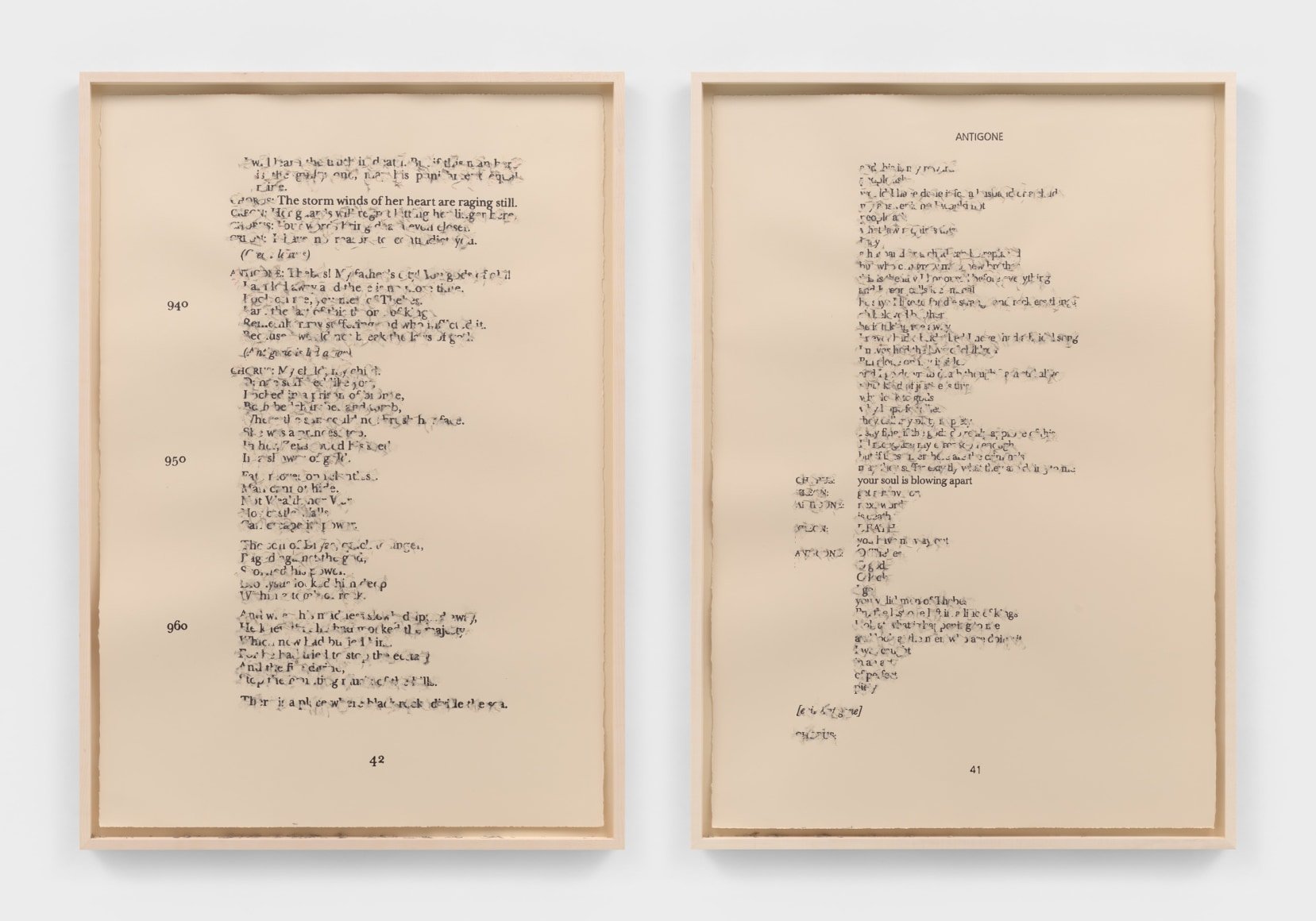

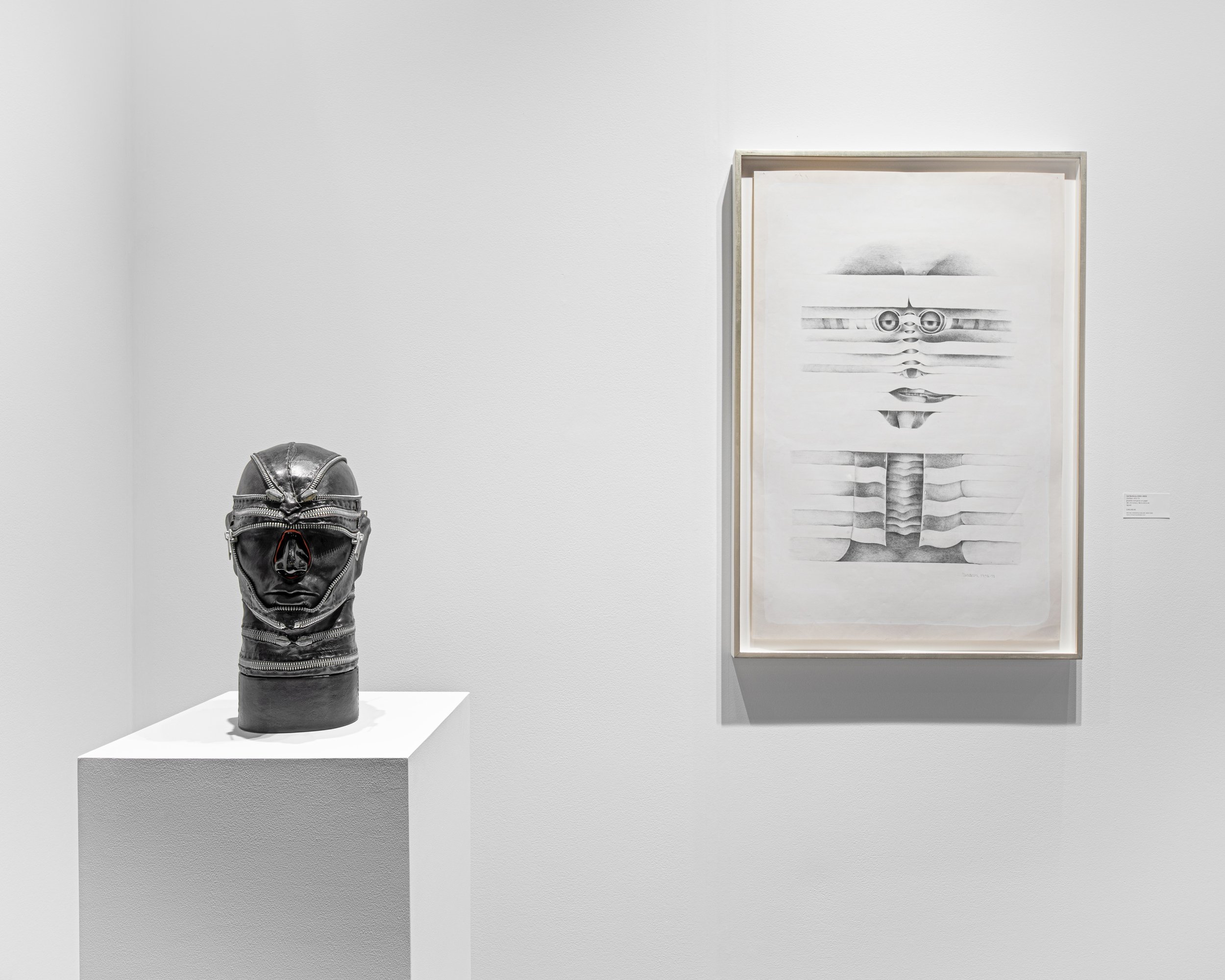

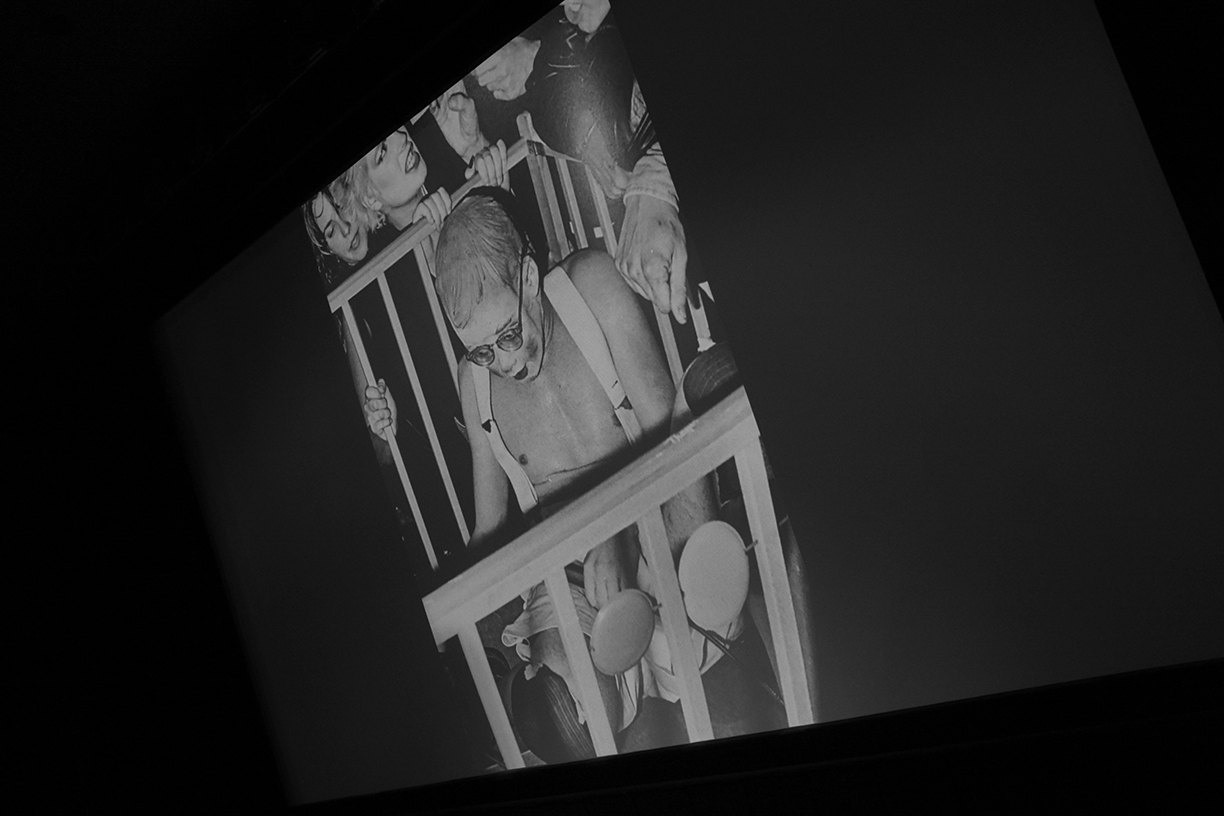

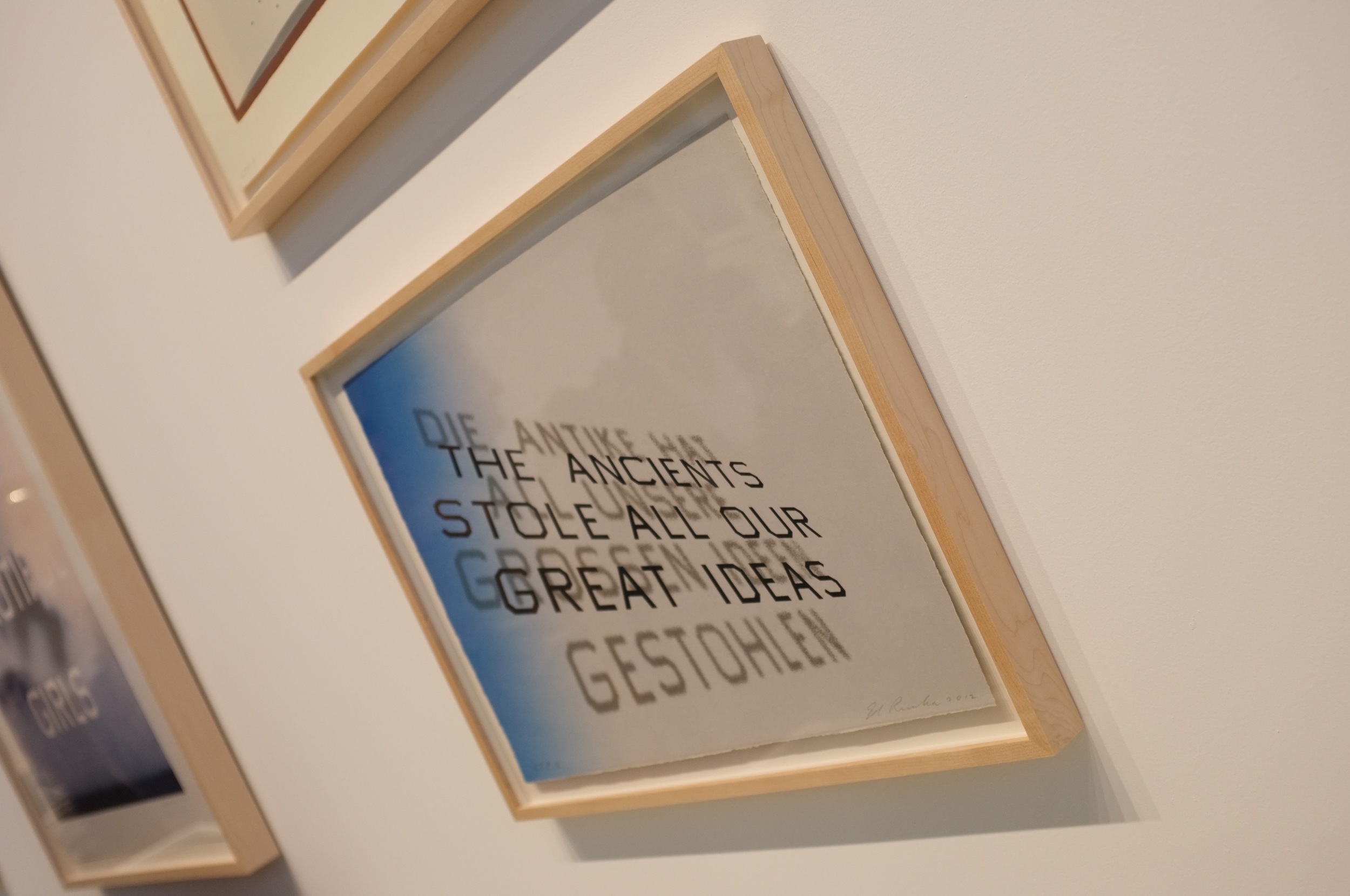

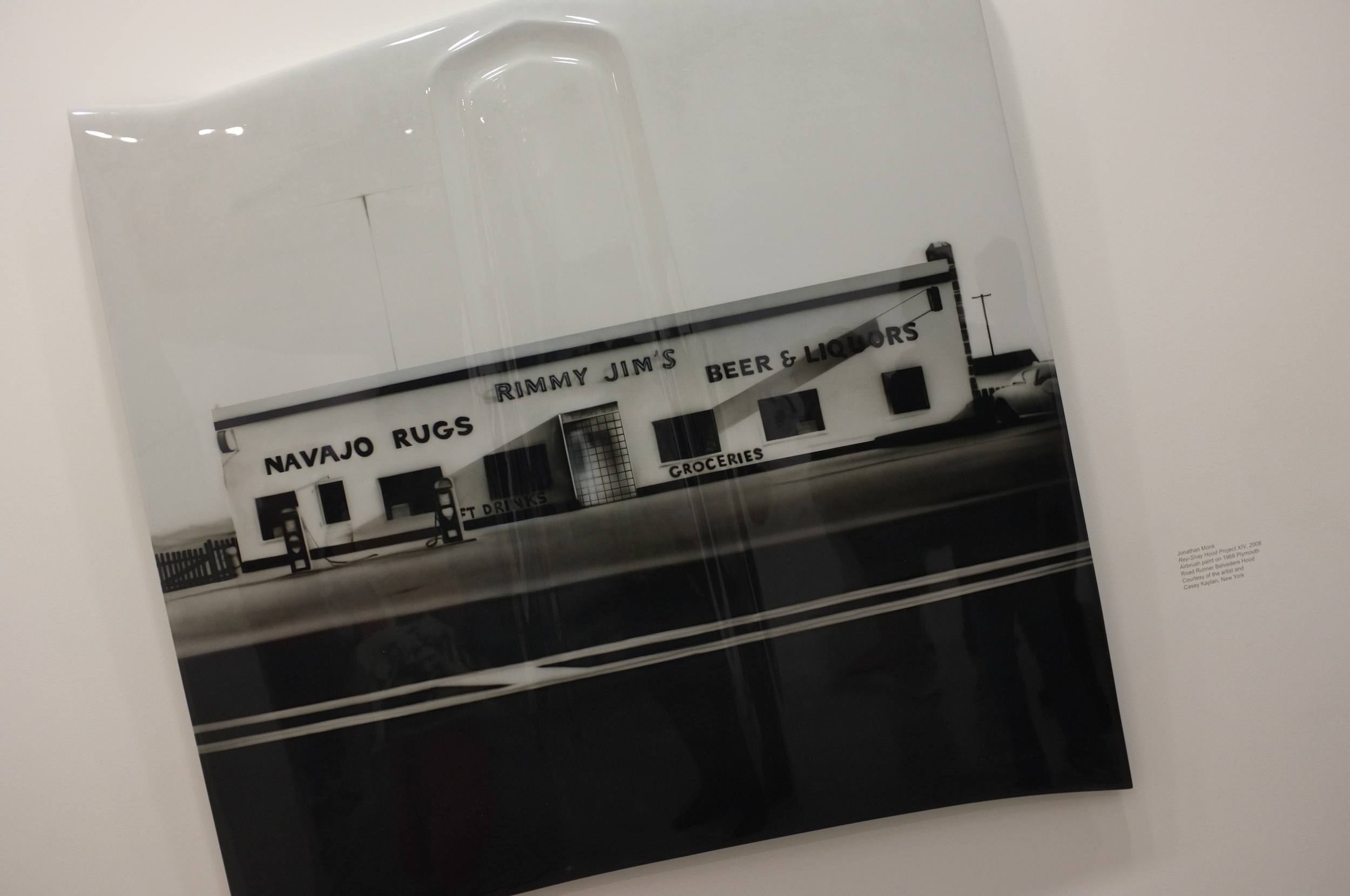

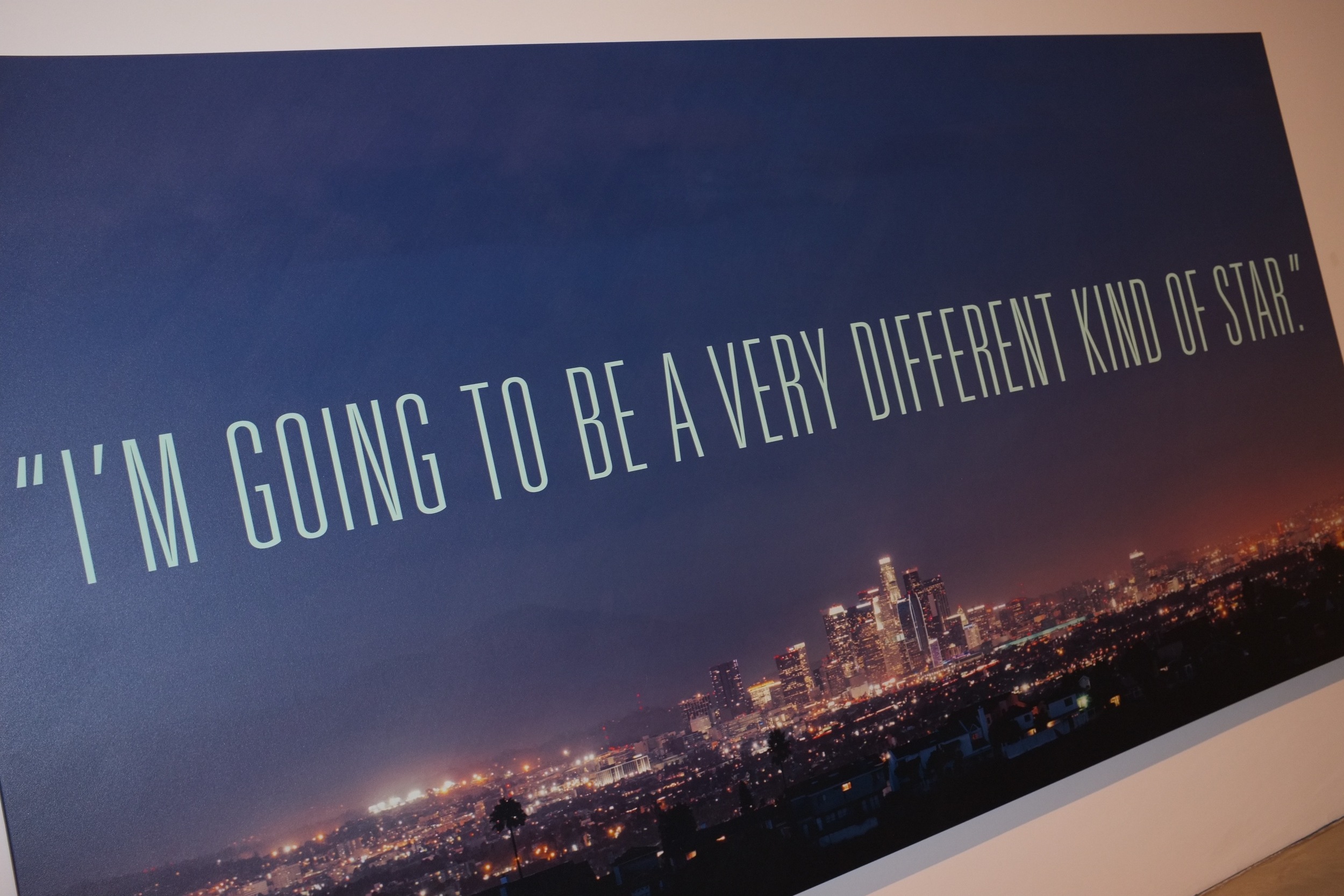

garcia’s literal self-expressive wardrobe let everyone know his state of mind: After opening three concurrent presentations across New York City (here at Frieze; at the nearby NADA art fair, at the San Francisco gallery Rebecca Camacho Presents’s booth, and at Artists Space in Tribeca, as part of the group exhibition Clocking Out: Time Beyond Management in addition to the recently closed solo exhibition esfuerzo at James Fuentes on the Lower East Side, the artist was finally free to rest for a little bit. la llorona also comes into the fair along with a wave of other politically and historically centered artworks featured—and celebrated—in the commercial context of having lots of very expensive work on offer (or, even more likely, no longer available). While the past several years of global art fairs have been characterized by glossy abstraction and mirrorlike installations, the booths on view inside The Shed on the West Side’s High Line made space for more nuanced, sensitive forms of art. Company Gallery presented a trio of abstract paintings by Tosh Basco, which could have been an element of the artist’s poetic, fragile movement performance at the new Water Street Projects, a curatorial initiative in the Financial District, a few nights earlier; Michael Rosenfeld dedicated his gallery’s entire booth to works made in 1973, the seminal year when Roe v. Wade made its way through the U.S. Supreme Court; we are now living through the devastating consequences of its reversal. At Alexander Gray’s booth, Bethany Collins’s Antigone: 1998 / 2015 (2023), is a diptych of works on paper, which looks at race and language through handwritten parts of Sophocles’s ancient play. Tehran’s Dastan Gallery presents a survey of the past century of Iranian women artists, across a variety of challenging mediums and forms; Gagosian devotes its entire booth to Nan Goldin, who recently signed with the mega gallery; her heartbreaking images recall pain and loss as much as the golden sunlight that bathes her figures. Playful works, such as Jean-Michel Othoniel’s lustrous strands of pearls of every color at Perrotin offer moments of flirtation and light.

As the sun started to give a little bit in the late afternoon-to-early evening hours, the multi-floored crowd began to contract up and down inside The Shed; soon it would be time for happy hour everywhere. ektor took a couple of Dobel-stamped poker chips (clever objects to be “cashed” as free-drink tickets) for his friends and collaborators outside the party. It was time to celebrate together.

FRIEZE NEW YORK

2023, installation view

Artwork © Nan Goldin

Photo: Sebastiano Pellion di Persano

Courtesy Gagosian