interview by Oliver Kupper

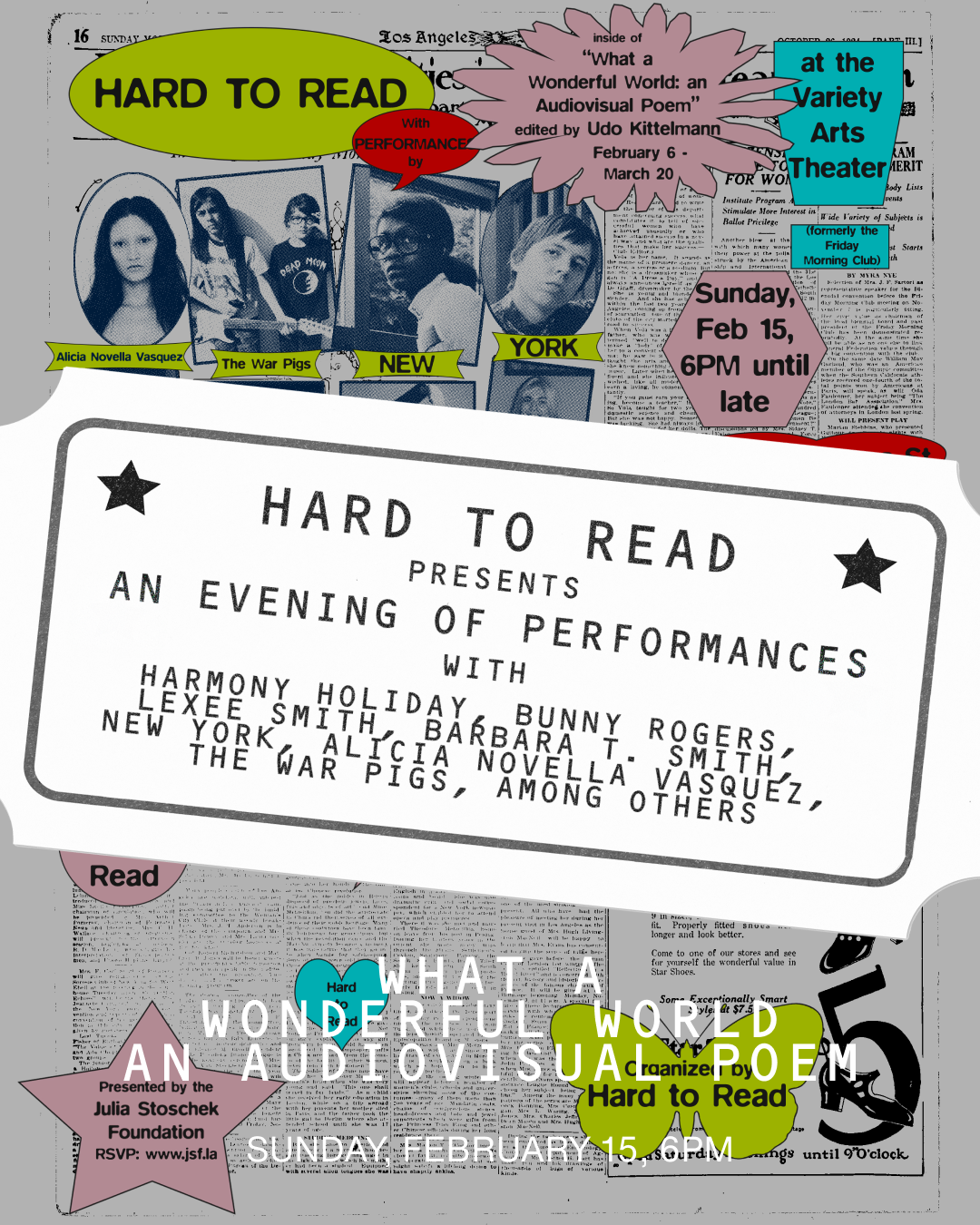

Over the past seven decades, Barbara T. Smith’s transformative practice has charted the evolution of feminist movements, performance art, radical action, self-liberation, time-based media, and collective organizing. In a similar spirit, Fiona Duncan launched the literary social practice Hard To Read in 2016, and she is now presenting a special edition within Julia Stoschek Foundation’s audiovisual poem What A Wonderful World. This program spans multiple floors and features a rare recreation of a 1970s performance by Smith. Joined by Mara McCarthy—founder of The Box Gallery, representative of Barbara’s estate, and daughter of legendary artist Paul McCarthy—Smith and Duncan discuss the intersections of their practices, the lineage of feminist performance, and the enduring power of radical artistic experimentation.

OLIVER KUPPER: Let’s start with Hard To Read, which you’ll be organizing at the Julia Stoschek Foundation. What can we expect? And can you speak to the scope and expansiveness of this endeavor?

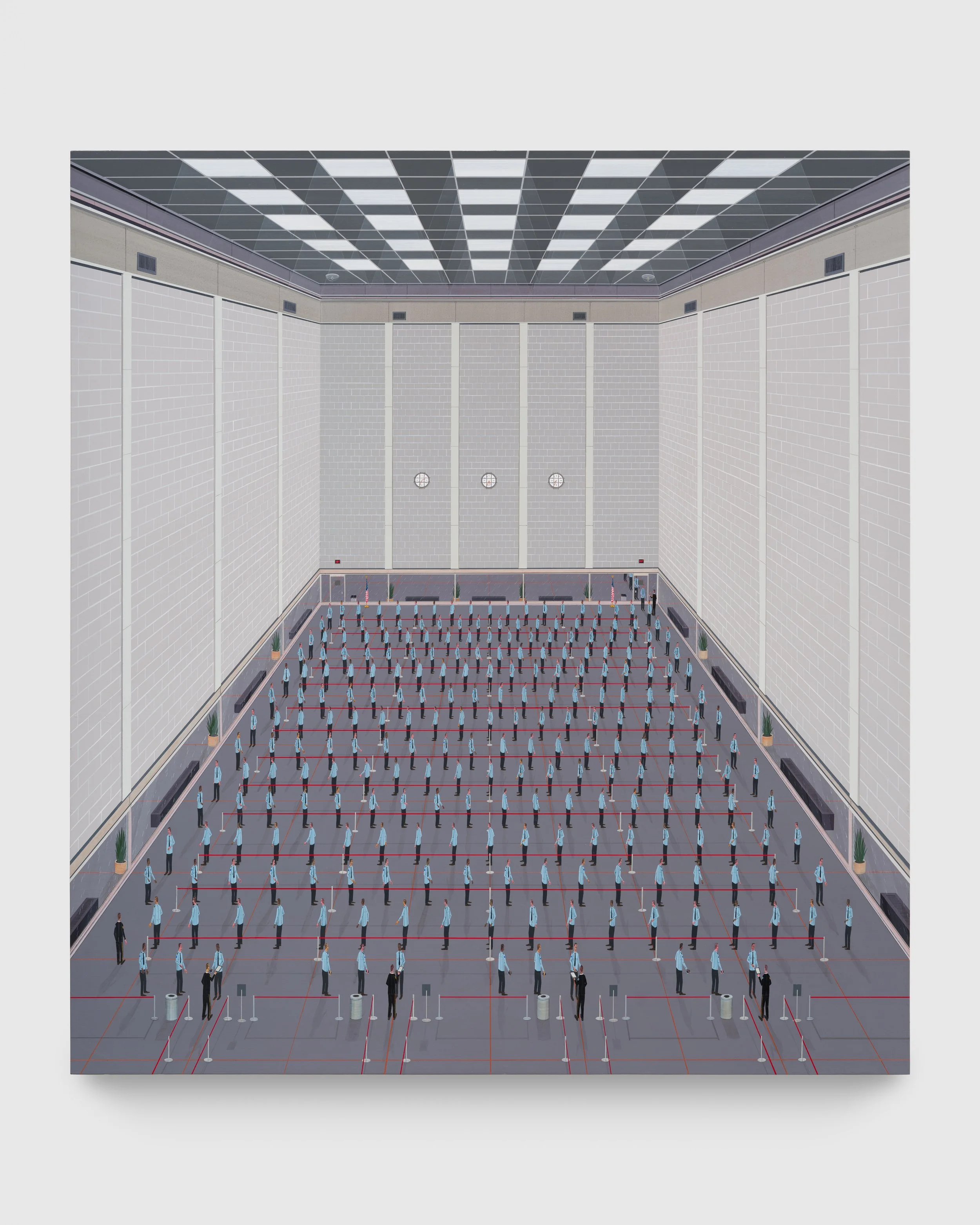

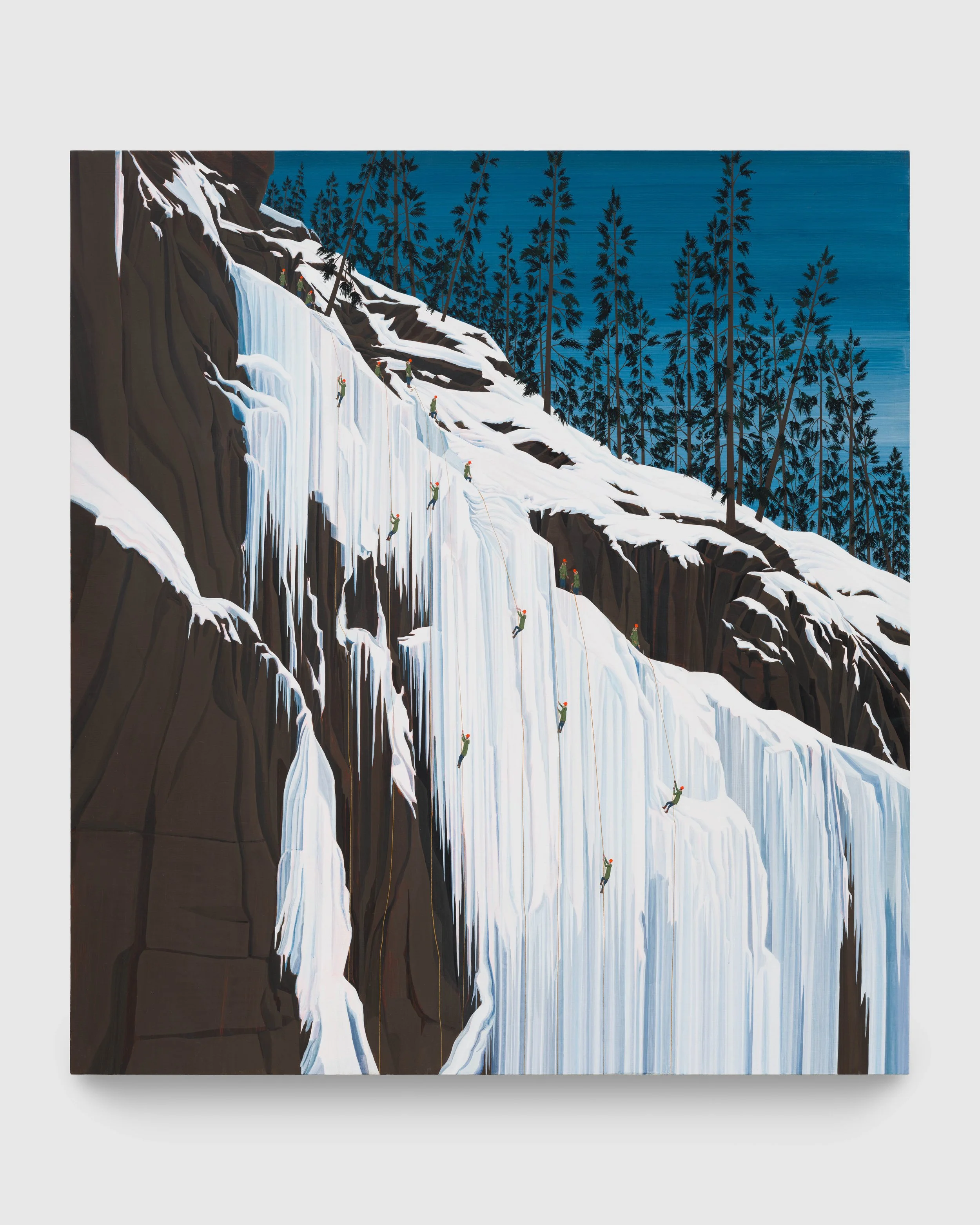

FIONA DUNCAN: I was immediately inspired by the building, which was originally erected as the Friday Morning Club—founded by suffragettes. It later became the Variety Arts Theater and went on to host all kinds of events. I’ve heard that even Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin made appearances there, and that it later became a venue for punk shows and more. My program really leans into those feminist origins. It’s a femme-centered program—something Hard To Read has always been. That reflects both my interests and my bias. When I saw what Udo was curating in the space—this sweeping selection of works grappling with American violence, global violence today, and the impulse to rise above it—I noticed some of Barbara’s contemporaries who also made video work alongside performance art, like Paul McCarthy and Chris Burden. And I thought: We need Barbara in this. It felt essential. I was absolutely thrilled when she said yes. There will also be eight additional performances, and the program is intentionally multi-generational—something I always try to prioritize. There's dance, theater, music... It’s like a variety show.

MARA MCCARTHY: Barbara, I feel like, especially when you first started, that distinction was crucial: the difference between black-box, theater-style work and early performance. None of it existed within the context of a theater.

BARBARA T. SMITH: See, I don’t think theater’s important. It’s all learned—like dance. It’s about pretending to be somebody else, and it’s meant for an audience. Performance art was none of that. We didn’t memorize lines. We weren’t doing it for an audience. It happened out in the world, often spontaneously. It carried a different meaning. It wasn’t about creating intriguing interactions between people—it was usually something the artist did themself.

DUNCAN: I think it’s only changed because of material conditions. As the cost of living has risen, younger artists need to be connected to some kind of revenue stream or institutional structure—it’s incredibly difficult to survive without money. Life is expensive. At the same time, the art world has absorbed many radical practices that once existed independently—through experimental theater, alternative spaces, or other autonomous contexts. Now, those practices are largely held within the art world.

SMITH: We didn’t have an audience in mind. We made the work for ourselves and for our friends. And every so often, outsiders would wander in.

MCCARTHY: Well, if we look at the performance you will be doing on Sunday, it was mostly for the public.

SMITH: We didn’t publicize it to the public to try to get an audience. We just said, “I’m gonna do this piece on Saturday. Come and see it.”

DUNCAN: You are doing one of your groundbreaking performances from 1975. What’s wild is that you did three performances in a single month—March of ’75—according to your book right here. That’s a remarkable amount. One of them was What Would Dogs Say When They Bark.

SMITH: For What Would Dogs Say When They Bark, we had someone bring a couple of dogs. The idea was to see what would make the dogs bark—what actions or sounds could provoke them. In the first part, I sat on a stool against the wall, my skin painted completely white. I think people were throwing things at me—there’s a picture of me sitting like that. Then a group of four women joined in. Each wore fabric and clothing in a distinct color—red, orange, green, and blue. They began singing and moaning spontaneously—not a structured song, just sounds. All of this was happening alongside the “throwing” segment. We even played a recording of dogs barking, hoping it might trigger a response from the live dogs. It went on and on, and honestly, I don’t remember if the dogs ever actually barked.

KUPPER: Your performance on Sunday night uses some pretty advanced tech. The use of technology has been central to your practice, and you’ve never hesitated to embrace new innovations. Like Xerox technology.

SMITH: The Xerox books grew out of my experience at Gemini [G.E.L.]. I brought a drawing and asked if I could make a print of it. They told me that usually, artists come through a gallery—and I didn’t have one. They acted like they’d never heard of me and said they wouldn’t do it. At the same time, a famous artist was printing there. As I drove home, I realized they were just brushing me off. I was really angry—completely pissed.

I started thinking: What’s the technology of our time? It can’t be ink on a soft lithography stone—that’s too old. What would be the new technology? I thought maybe business machines. I looked at blueprints and other office technologies, and the one that seemed truly revolutionary was Xerox. It doesn’t use ink—it uses tiny plastic beads. It’s electronic: the plastic dots are charged to replicate the image, pushed through, and fixed with heat. Heat melts the plastic and transfers the image.I got a Xerox machine and set it up in my dining room. I made thousands of prints, and tons of books.

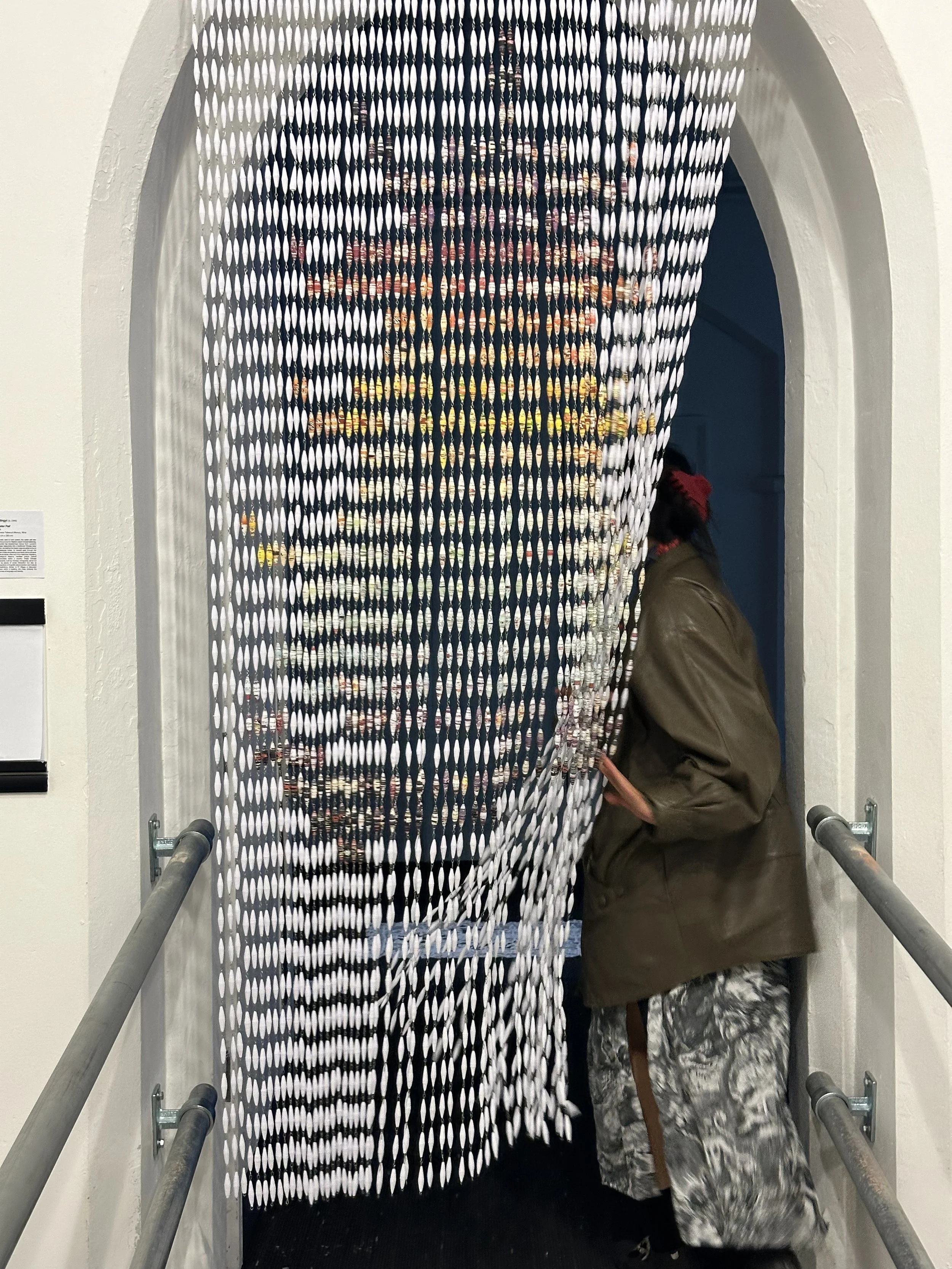

DUNCAN: We’ll have copies at the performance on Sunday. There will be a lot of surprises in store and things people can take home with them.

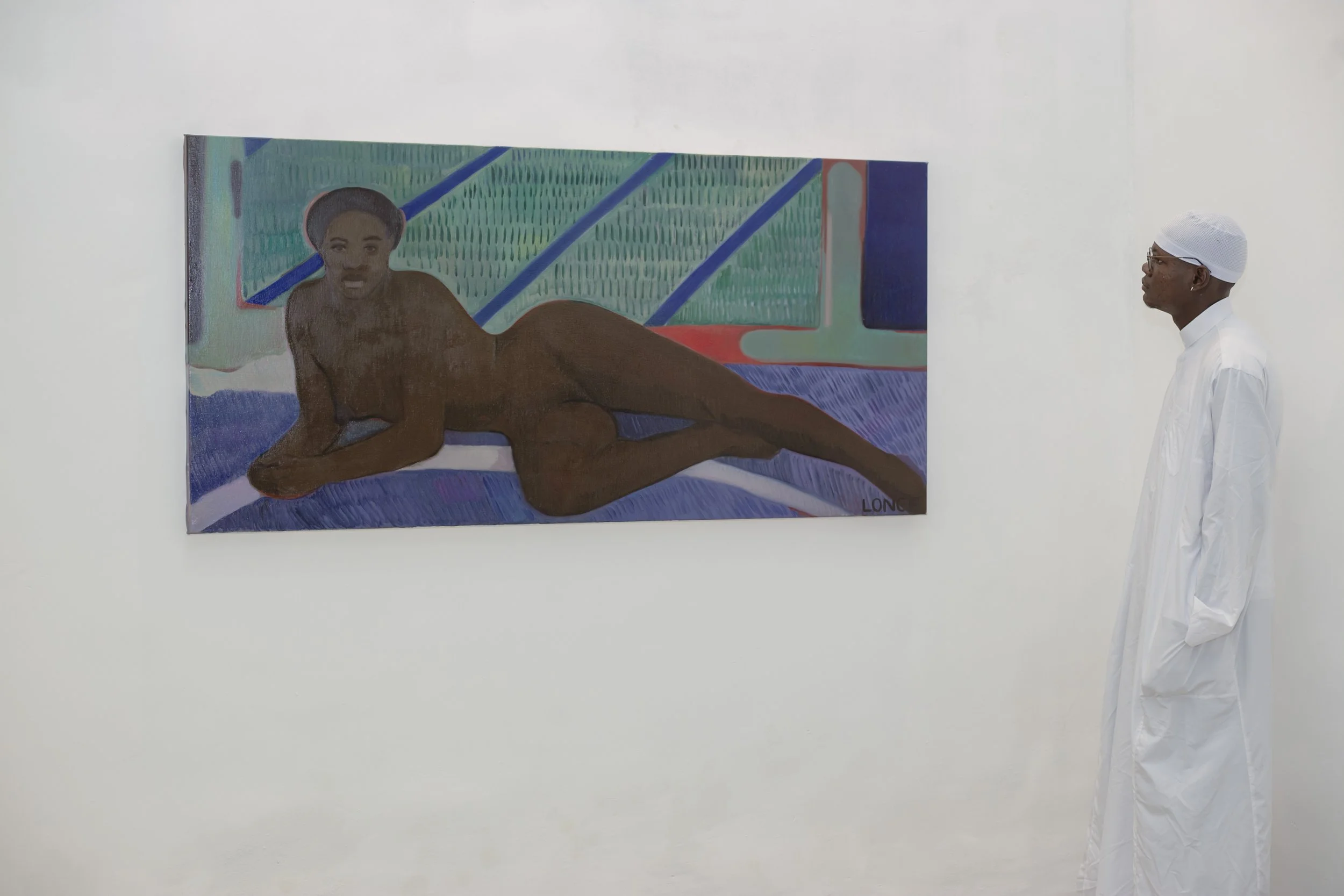

Click here to RSVP for Hard To Read on February 15, a roaming night of live activations and readings staged throughout the spaces of the Variety Arts Theater. With performances by Bunny Rogers, Lexee Smith, Barbara T. Smith, Patty Chang, Harmony Holiday, Alicia Novella Vasquez x Maya Martinez, Matt Hilvers, The War Pigs, and NEW YORK With books by Bunny Rogers, Barbara T. Smith, Patty Chang, Harmony Holiday, Maya Martinez, Fiona Alison Duncan, Jason De León, and Coumba Samba