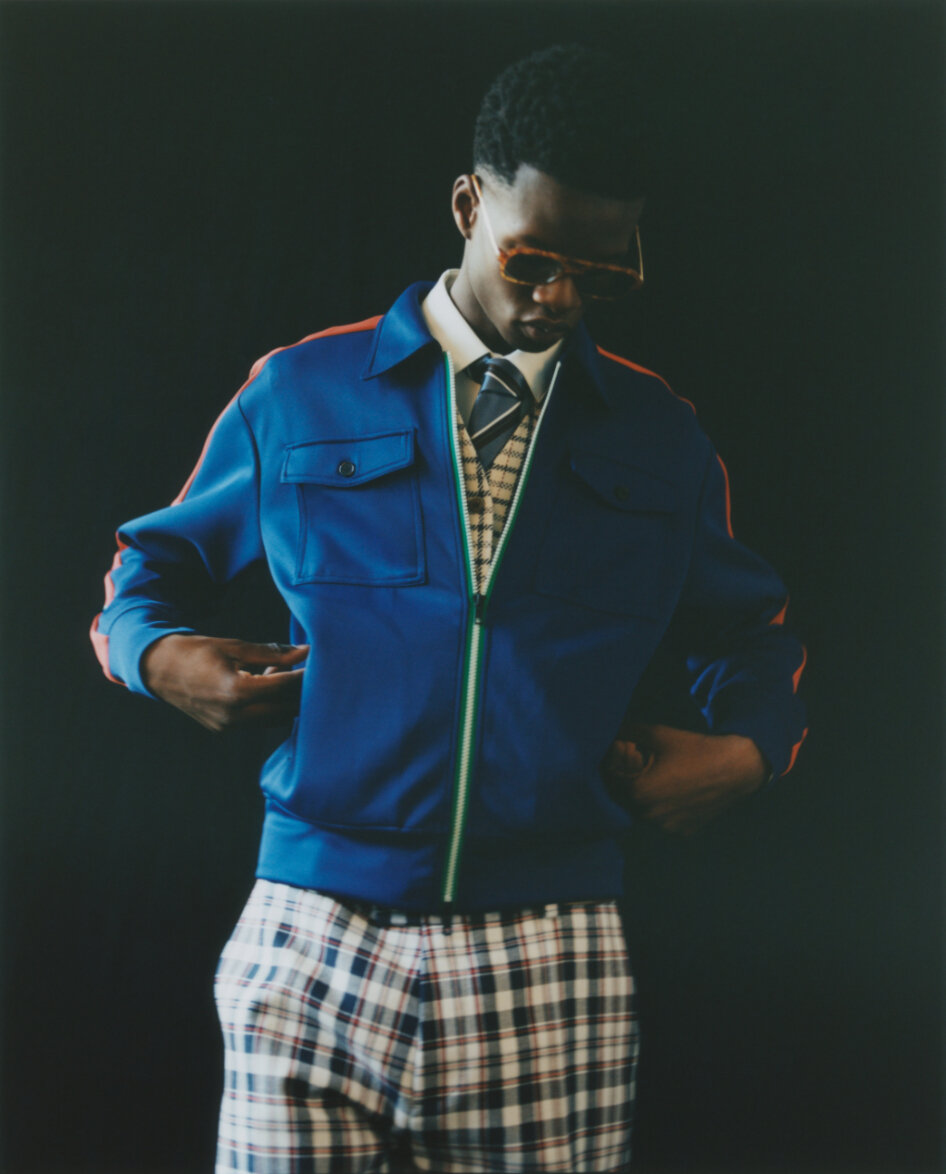

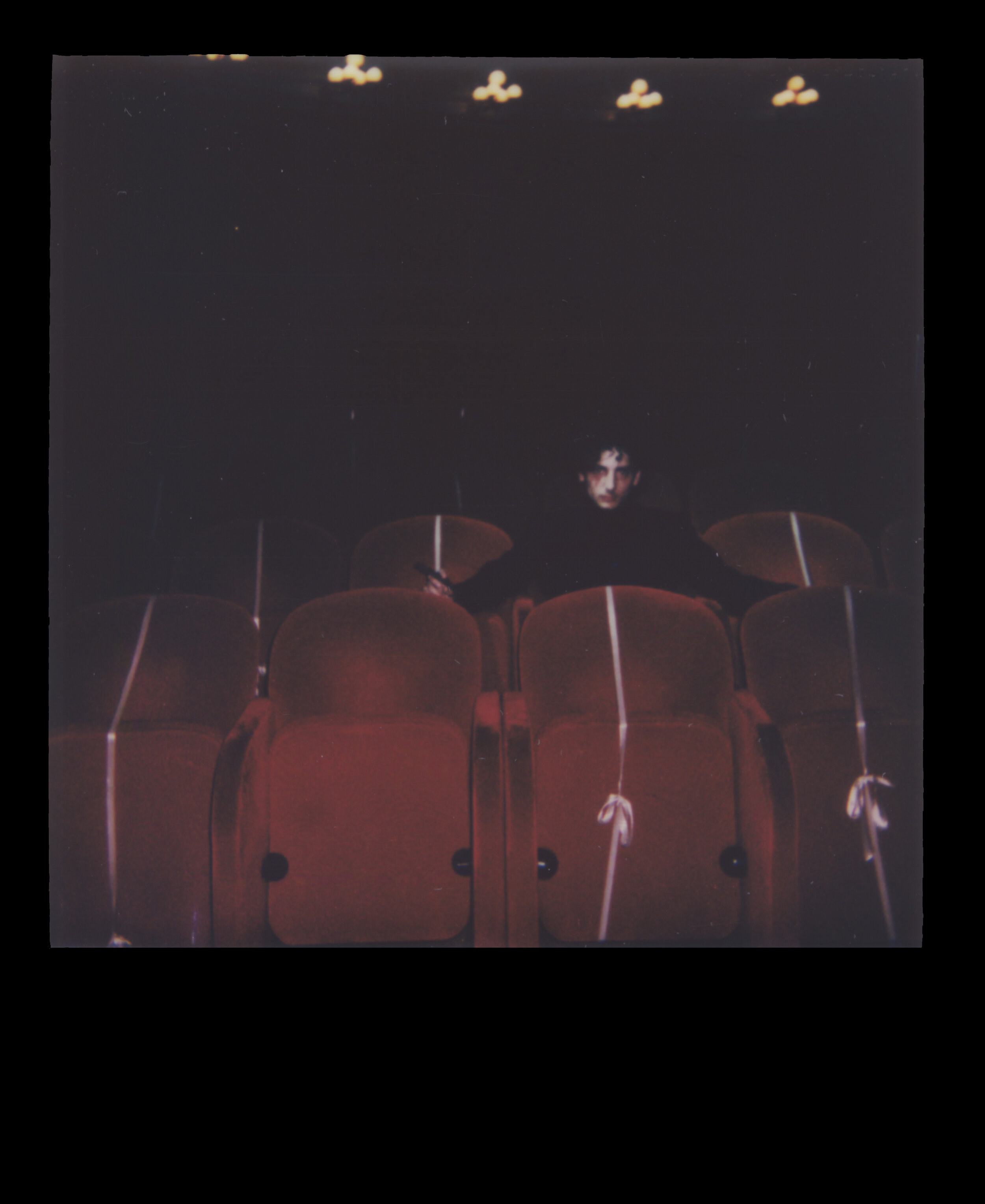

Photograph by Agustín Farías

In the fall of 2020, Kenny Eshinlokun launched her creative agency, Taboo, to create world class projects that transcend audiences and industry borders. After working for a decade in the marketing and music industries, she saw the need for artists to build meaningful, long-term partnerships with brands that truly care about their creative endeavors. Through Taboo, she has built a global cohort of creatives and brands that are committed to giving back to their communities and building relationships that are rooted in genuinely shared visions. Autre caught up with the Eshinlokun to talk about the inspiration for starting her own agency, the meaning of true inclusivity, and the future of Taboo.

AUTRE: What was the creative scene like for you growing up in London—how did you connect to the subculture?

KENNY ESHINLOKUN: My background in London lay heavily in the music industry. The industry is really hard to break into but once you’re in, you’re pretty much in, and I quickly found the industry super small. My connection to subculture and my career had always been separate when I was young, I had a lot of friends who studied fashion and knew a few people working at Supreme and Lazy Oaf during their rise, which was really interesting to watch.

Generally, street style was always extremely special in London and encompassed influences from all over the world, which also meant influences from many subcultures, like grime, the rave kids, skaters, punks, b-boys. I myself used to dance, which was a scene that had so many layers, and I loved being a part of this bubble the most. Dancers are the funniest, most energetic and craziest people you'll ever meet. It's a scene that really made me understand what community and second family was and really drove my connection to music through movement.

AUTRE: What kind of music did you listen to growing up?

ESHINLOKUN: As a kid I listened to a lot of R&B, hip hop, and pop music sprinkled with the tiniest bit of emo, punk rock, and as I got into my teenage years I discovered classical, house, and techno music. Mainly because singing along to Destiny’s Child whilst studying for my exams was too distracting, so I needed music without too many lyrics.

AUTRE: What made you want to start your own agency?

ESHINLOKUN: I mainly started because I couldn't find a job in the role that I wanted and a good friend of mine, Peter, who had started several companies himself, encouraged me to go for it. I wanted to create a space for people in the industry who looked like me and cater for an audience that was more inclusive.

AUTRE: What is Taboo? Can you describe the agency and what its core objectives are?

ESHINLOKUN: Taboo is a brand-partnerships company that has a soul, I guess. We try to add meaning to everything we do and pride ourselves on the relationships we keep with not only our artists, but also the individual's who work for each of the brands with which we partner. We want to create bespoke, authentic partnerships that go a little further and give back to the community in some way, small or big. We want to provide opportunities for musicians to express themselves and share who they are. We want to encourage brands to see artists as more than just a face, and for musicians to see the brand as more than just a dollar sign. We want to create long-lasting partnerships that turn into strong relationships.

AUTRE: What does true inclusivity mean to you—is there something the media or people are missing in their message of bringing disparate communities together?

ESHINLOKUN: Inclusivity means making things accessible for everyone, regardless of whether they’re in the audience or not. You never know who might be a part of your audience, so accounting for everyone is true inclusivity to me.

AUTRE: In an age of multiple virus variants and lockdowns, can you talk a little bit about the challenges of bringing a community together during a time of social distancing?

ESHINLOKUN: It’s been very hard, since at Taboo we love a good party ,and have tried to bring together many parts of our community to celebrate and enjoy each other's company, but lockdown really hinders this.

AUTRE: What does subculture mean in a time when everything is on Instagram and TikTok—can a subculture thrive in a digitized, globalized world?

ESHINLOKUN: Subcultures to me can not truly exist in a digital sphere and thus the most amazing thing is to experience them in real life…

AUTRE: What does the word ally mean to you—how do we develop meaningful allyships in an age of wild division?

ESHINLOKUN: An Ally is someone who has your back when no one is looking.

AUTRE: What kind of brands or partnerships are you looking for—is there a magic word that they usually say where you know that they are the right partner?

ESHINLOKUN: Partnerships that leave an imprint of unison, something that really feels like both parties sprinkled some of themselves and it couldn't be replicated by anyone else as it's completely unique to the unison.

AUTRE: Where do we go from here—what are your grand plans for Taboo?

ESHINLOKUN: I want to do more clothing/fashion collaborations. In general, those are the most interesting for me and hopefully Taboo as a brand can also develop some collab rotations of its own.

AUTRE: As a leader in the community, do you have advice for those who want to take charge and help amplify voices?

ESHINLOKUN: Make sure you know why you are speaking up, as when people try to put you down, you'll be able to brush it off because you know, at the very least, you truly believe in what you are saying.

Follow Taboo on Instagram to learn more.