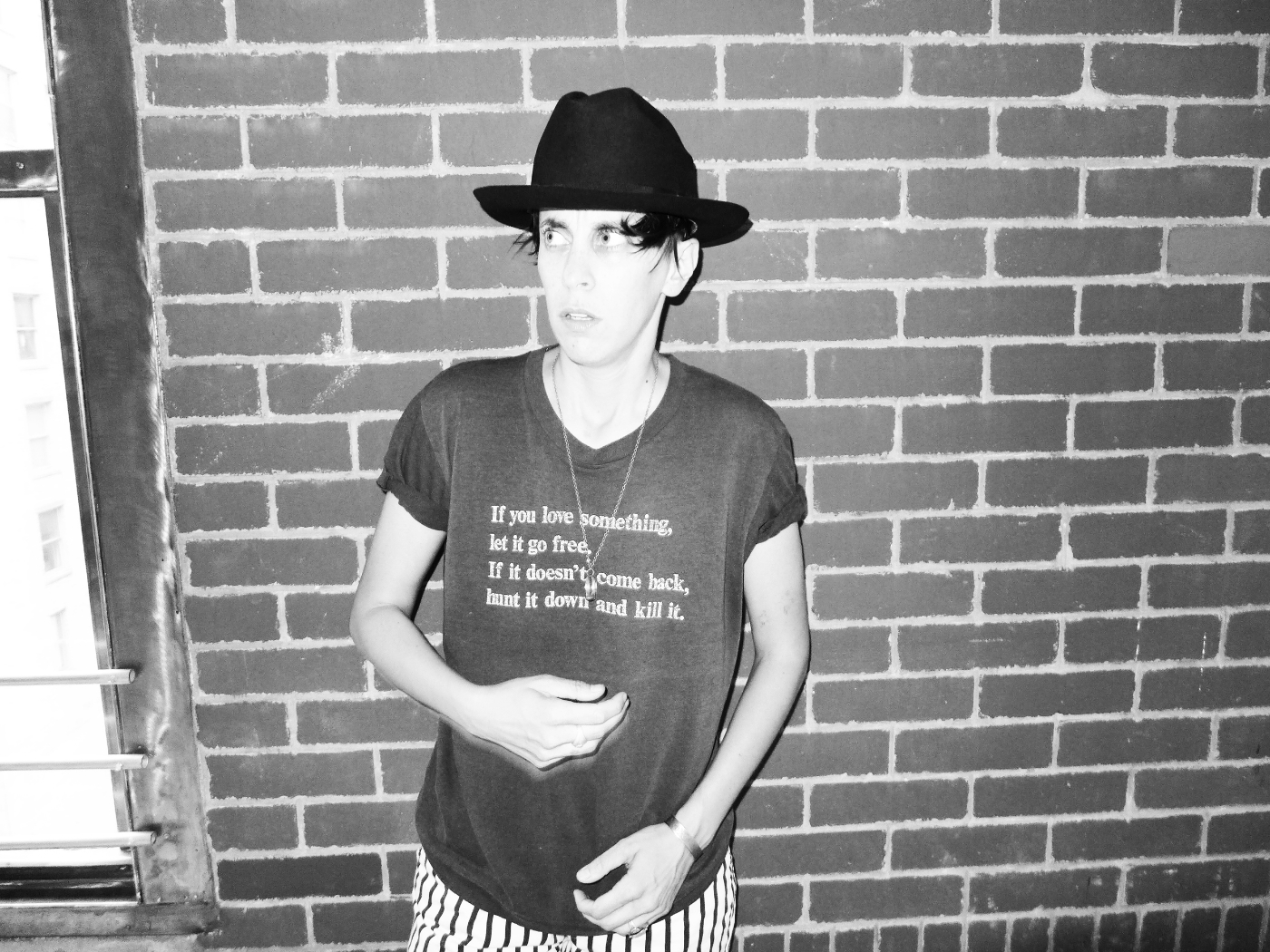

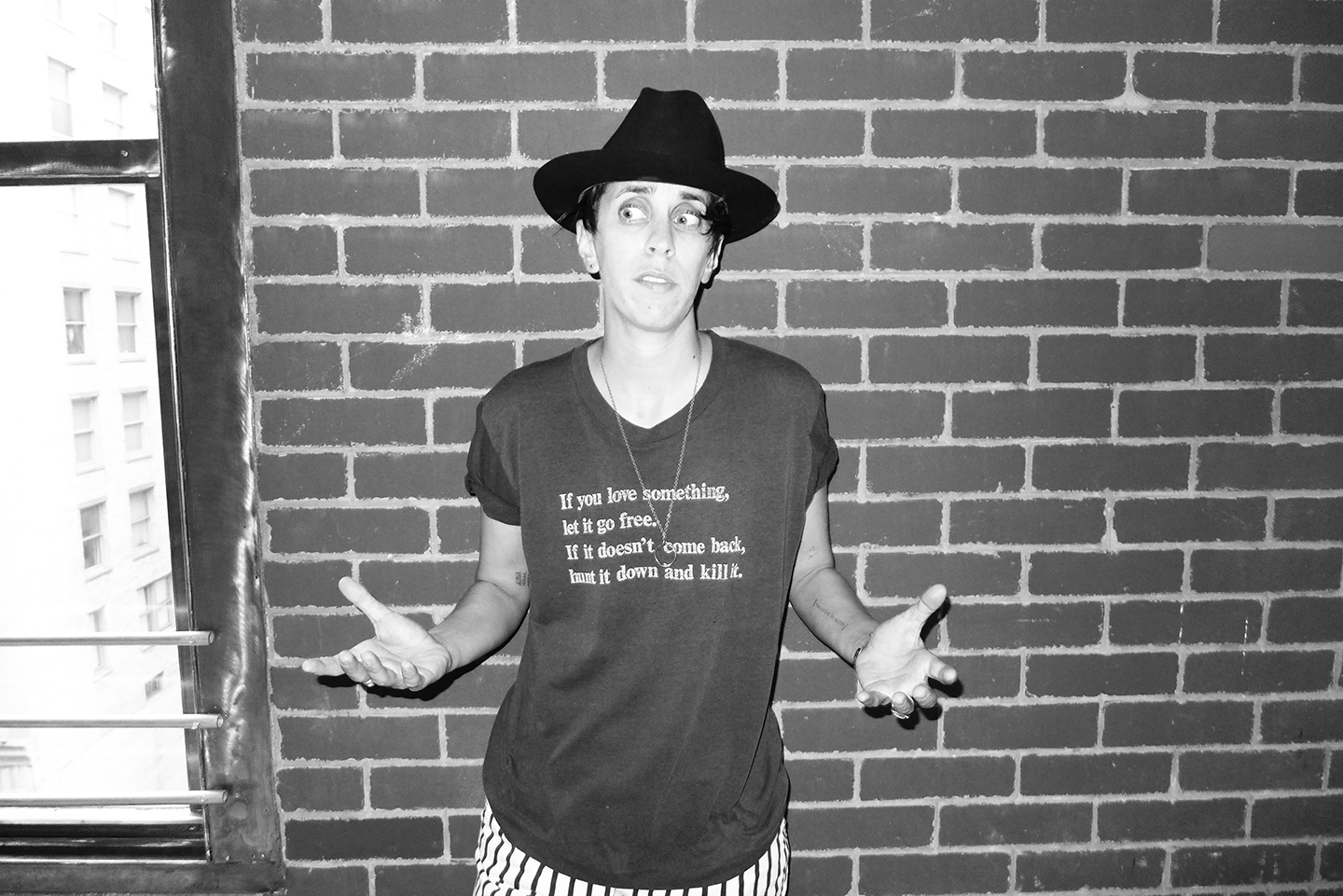

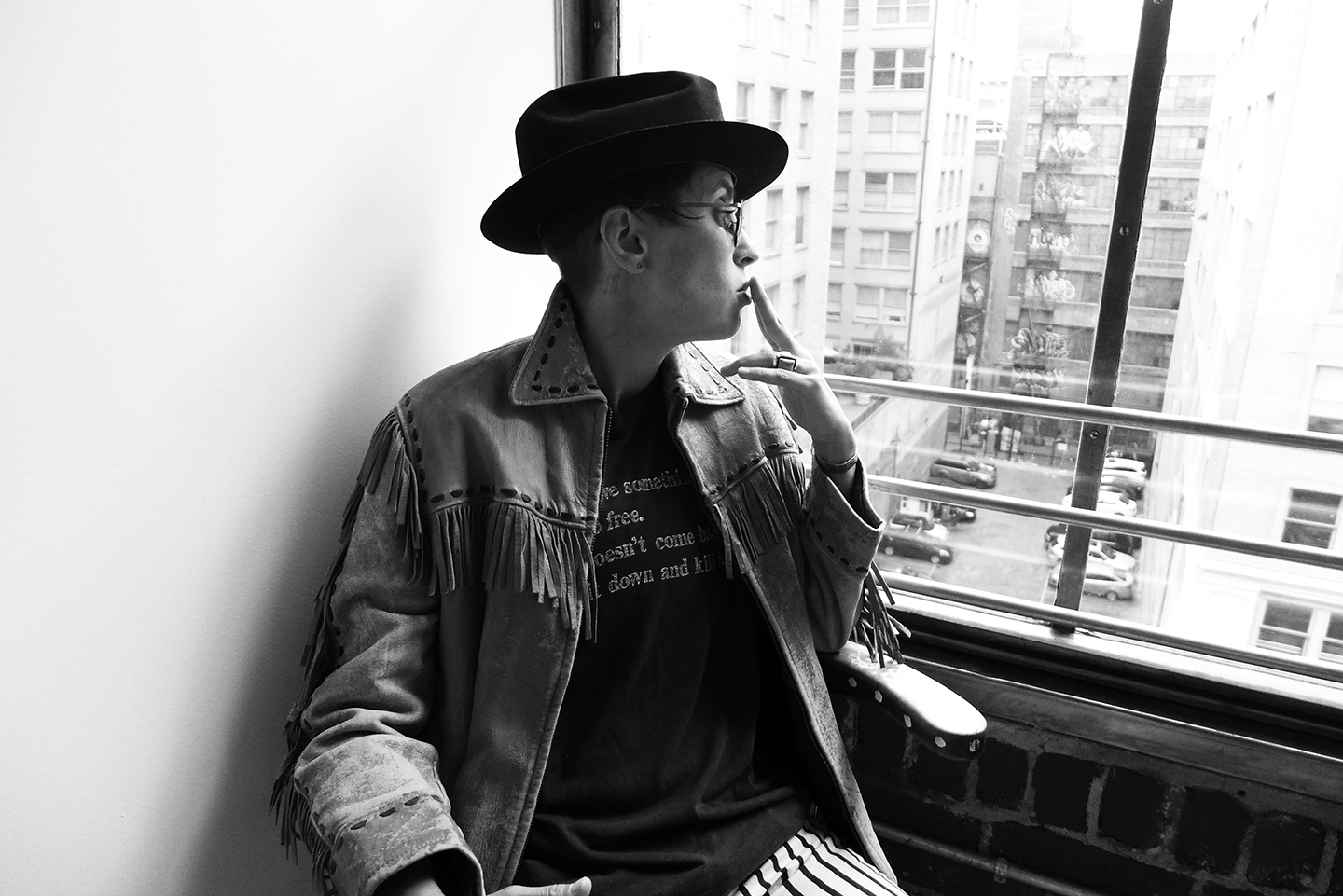

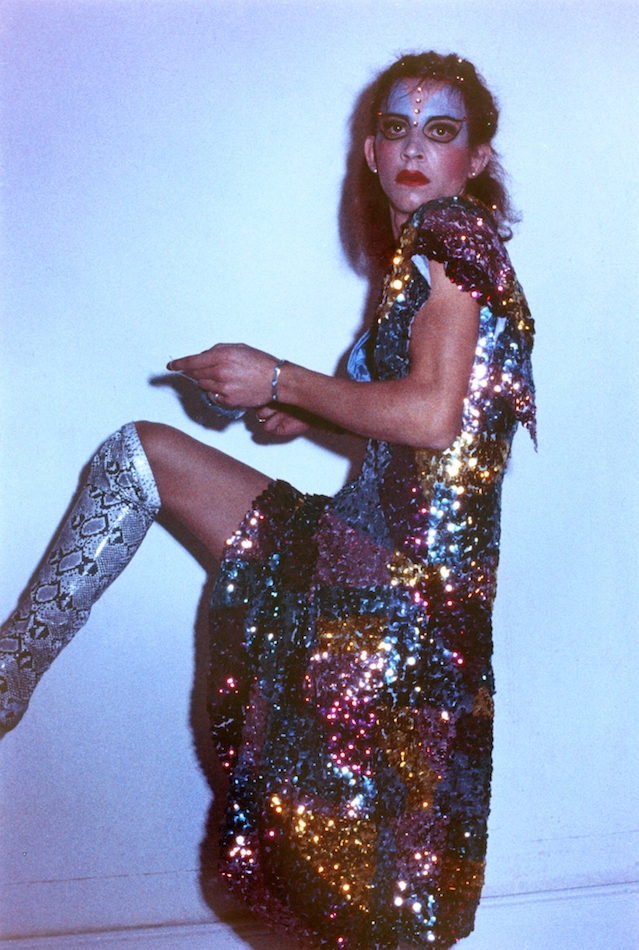

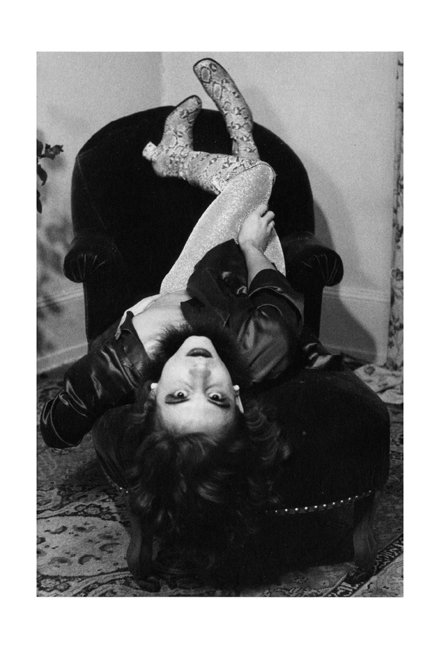

About a month ago, Autre was asked to cover the second Summer Sacrifice for How Many Virgins? at the Ace Hotel. If that doesn’t make any sense, it’s because it doesn’t. Little did we know that we would be introduced to one of LA’s most enigmatic, energetic, and multifaceted performing artists by way of a hilarious mock acting reel spanning 10 years of highly varied and absurdly captivating film projects. From parodic audition tapes for films like Pretty Woman, to the superimposing of her character on iconic ‘90s infomercials, to abstract layerings of sound and industrial imagery, Mel Shimkovitz’s work is at once arresting, captivating the viewer with a chameleonic quality that leaves you anticipating the next impressive transition. It is perhaps that chameleonic quality that makes Mel so fascinating. The moment the reel finished playing, I immediately scanned the audience for this curious specimen in hopes of a handshake and the prospect of an interview. Little did I know the magnitude of the Pandora’s box I was about to open.

Researching Mel’s work before the interview, I found a wide range of recent, mostly acting work (she’s popped up in skits on Funny or Die and has made cameos in varied televisions series), but struggled to dig very deep into the past. She would later explain that this is due to a slew of pseudonyms she used throughout the early aughts in order to protect the Shimkovitz family name—a nice Jewish family from Chicago. In the following conversation, Macho Mel (as she is known in some circles) covers a dizzying gamut of work and life experience. There was her meeting with William S. Burroughs as an adolescent in Lawrence, Kansas. There was her founding of the Voodoo Eros record label, which released music by the likes of Devendra Banhart, CocoRosie, and Antony and the Johnsons. Voodoo Eros also took the form of a retail store that she ran with CocoRosie’s Bianca Cassidy—it was more an elaborate conceptual art piece than a real retail experience. But next year may change everything for Mel, because she will find herself in a reoccurring role on Jill Soloway’s groundbreaking series Transparent, which just cleaned house with five Emmy awards. We can’t wait to watch.

Indeed, Mel’s approach is wacky and unbridled, yet focused, professional, and somehow she seems to be completely devoid of pretense. She is familiar, but also alien in her virtuosic comedic talents that have an almost vaudeville vibe, but maybe it’s just her willingness to fall over to make an audience laugh. It’s the best kind of comedy, because it’s real and authentic. In the following interview, Mel and I chat about Trans vampires, her Zelig-like position in the music, art and Hollywood worlds, and the media’s sudden shift in focus toward the lives and rights of the LGBTQ community.

Summer Bowie: So, I loved the Melvira work you produced with Amy Von Harrington at the Ace Hotel. Can you talk a little bit about how that came together?

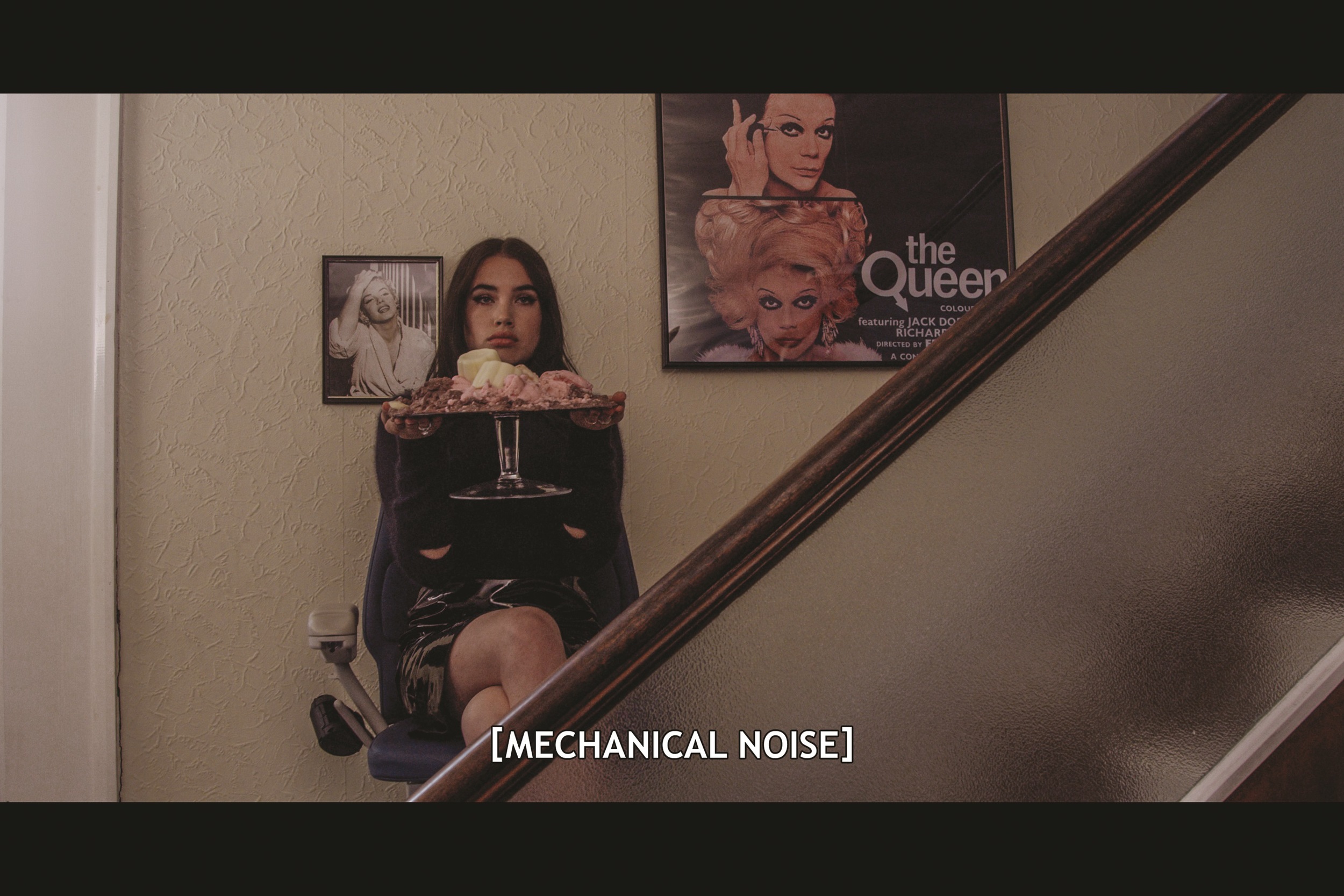

Mel Shimkovitz: Ben Lee Ritchie Handler and Ava Berlin have a project called How Many Virgins? They asked me if I had any videos I wanted to be shown, because I had been making videos with Amy for a long time. So, I had all these years of work and I thought it would be a nice opportunity to dig into the archives. We had some extra time, so we made a new reel that was really influenced by the Hollywood vibe. When I came out to LA, being an artist quickly transformed into being an actress. Not just in art stuff, but in the semi-mainstream as well. Amy has been making reels for me for a while, and we got the idea to make a fun reel for once. She’s obsessed with Elvira, so we created the character “Melvira”—Elvira’s cousin, who came out to LA wanting to make it. She’s an awkward trans vampire—Melvira: Mistress of the Stage and Screen. So the video screening was Melvira’s acting reel.

SB: That seems pretty surreal. How did you meet Amy Von Harrington?

MS: I was running a record label at the time. I was doing a huge mailing of promos in Brooklyn. She was standing behind me at the post office, deciding if she hated me or not, as I spent an hour holding up the line. Later that night, she showed up at a party that I was throwing with Bianca Cassidy for our project Voodoo Eros. We had a fried chicken party that night and I recognized Amy from the post office. That was it. We just started hanging out and working together. And it’s been like that ever since. We’re casual burnouts. Lovable weirdos.

SB: Can you tell me about the Voodoo Eros project?

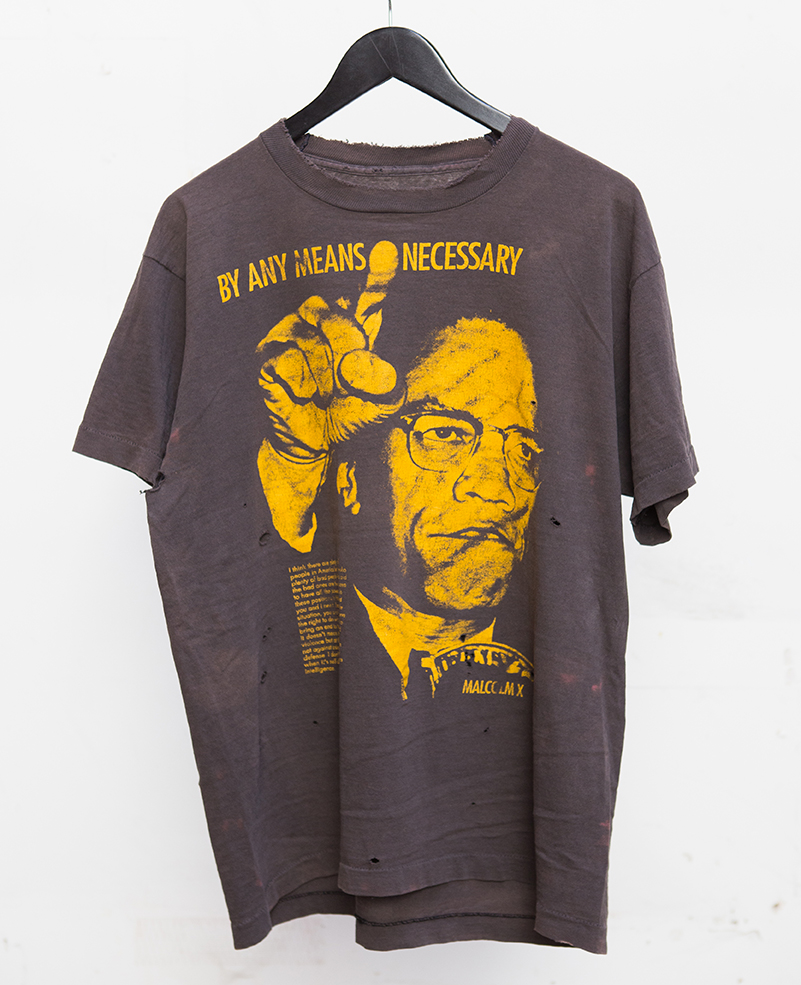

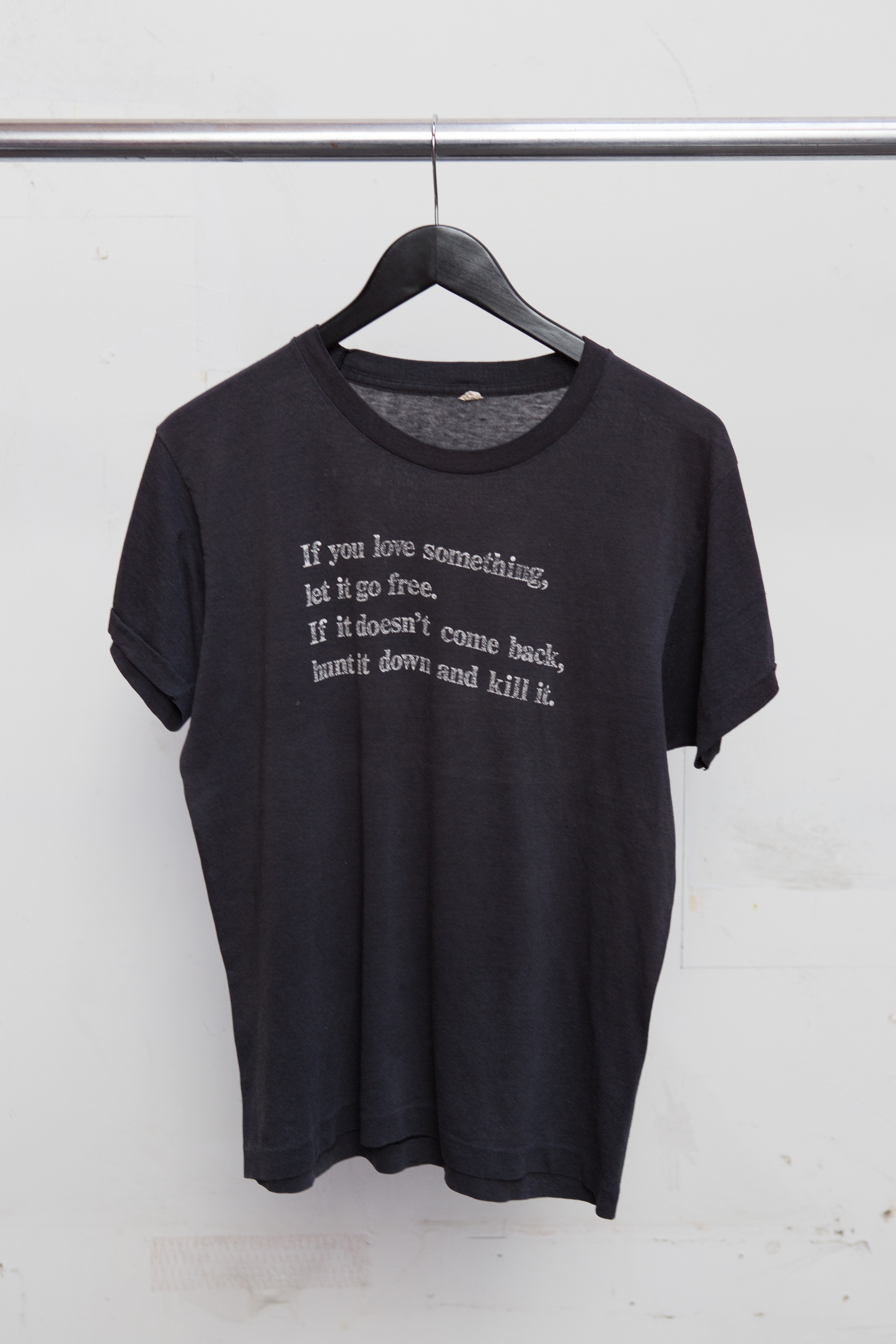

MS: Yeah, we had a store on the Lower East Side called the Voodoo Eros Museum of Nice Items. This was 2007. We were a record label, so we would record in there at night. But during the day, we sold XXXXXL sweatshirts and sweatpants that we had hand-painted. Our thing was “the biggest clothes on the Lower East Side.” It was such a small store that we could only put up one thing on each wall. They were all horribly priced. Some were $2 and some were $2,000. We also sold items from the 99¢ store across the street, but we would mark them up about 1,000%, but with really nice price tags. The only people who came into the store were Japanese tourists and dudes who would come in to gay bash us. Bianca and I decided that we were going to play shopkeeps for a year. To be a shopkeep, though, you have to have a long attention span and a will to make money. We didn’t have either of those things.

SB: Where are you from, and when did you first know you wanted to become an actor?

MS: I grew up in Chicago, but I left when I was 17 and went to Kansas. I was really obsessed with the Beats. I was obsessed with William Burroughs. This was before I knew what misogyny was. I was happy to meet him; he wasn’t happy to meet me. But he was very happy to meet the very good-looking guy I was hanging out with. Lawrence, Kansas is really a cultural mecca in the Midwest. There’s a legacy of major progressive hippies out there. It’s a major abolitionist town. That’s not to say that the Westboro Baptist Church isn’t down the street, and didn’t protest every play when the Harlem Choir Boys came to town.

Growing up in Chicago, you do a lot of improv and sketch comedy. I grew up doing community theatre and plays in school. When I went to Kansas and didn’t know what to do with myself, they took me in. There were so many communists teaching at the University of Kansas in the theatre department. That was a really political education—political theatre. I went from there to New York.

I was there for a number of years before I met Bianca Cassidy. We started this feminist collective called “Wild Café Theatre,” and no one was coming. But then Bianca and her sister started this band, and I started doing performance art for their shows in front of thousands of people. We were making videos and fictional worlds. We were queering the world. That time in my life, everything was a creative choice.

SB: Tell us about your period with CocoRosie.

MS: Our first album that we put out was just for fun. It was a box filled with tapes that friends had made. We put it out as an album called “The Enlightened Family.” We had songs by CocoRosie, Antony and the Johnsons, Jana Hunter, Vashti Bunyan, Metallic Falcons—just before anybody knew who these people were. All of a sudden, people were buying it! It was a cool project; we were doing whatever we wanted for a couple of years. It was a pure aesthetic project.

SB: Wow, that's amazing. Now, let's fast-forward to your life in LA for a second. As a performance artist, it seems like you’ve become this integral part of LA’s creative community, but it also seems like you’re gaining footing in the more mainstream Hollywood industry. Where do you feel most at home?

MS: In the past, I always would have said in the art world, because of my interest in all things beyond theatre and narrative—I’m super interested in poetry, abstraction, and psychedelic visualscapes, etc. But amazing things have happened in the past year. I’ve met such a great community of writers, directors, and performers. I have this super amazing TV and film community that I never had in the theatre and music worlds of New York. I found a really good tribe. Now, I would say I feel really good in both places, which is so cool. So, I don’t know, I’m really just trying to be very charming, super polite, show up on time, do whatever’s asked of me, have no ego at all moments, and be ready to humiliate myself. I think that’s it.

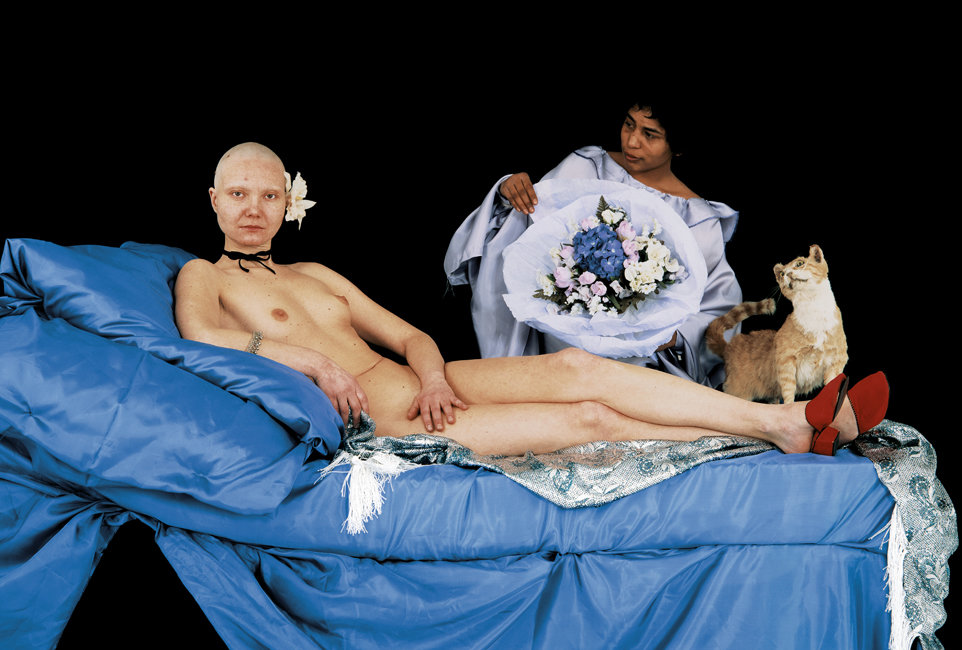

There’s this idea that nice guys finish last, but I’m getting the feeling that nice guys are getting ahead. In the art world and the Hollywood world, the thing that they have in common is negative competitiveness. The art world is held back by its own self-reference, which makes it super exclusive. The Hollywood world is held back by its own nepotism. Which doesn’t work for anybody who isn’t a straight white cis male—there’s no community for them. People are realizing the patriarchy of that doesn’t work for them. We’re seeing change now. When the first Whitney opened, there was not one woman artist. In the new Whitney, there is amazing work by female artists on every floor. It’s a mindful and purposeful choice, but that’s how equality happens. The cameras are finally being put in the hands of women, queer people, people of color, trans people, people of different ages even.

"I’m really just trying to be very charming, super polite, show up on time, do whatever’s asked of me, have no ego at all moments, and be ready to humiliate myself."

SB: Have you noticed any differences coming to LA from New York?

MS: Coming here, people are starting to collect and to pay attention. All kinds of people can be a part of it. It’s so optimistic out here. Being an artist in New York feels like you’re part of an industry, part of the company. But being out here, especially for the first few years, it felt like being an outsider. And isn’t that who should be creating new culture in a community? The people for whom the current culture isn’t working?

SB: What would you say has been the catalyst for the boundary pushing we’re seeing in regard to gender and sexuality in the media today?

MS: I want to say that it’s been people who identify as queer rising up and forcing their voices to be heard. But nothing happens without the majority paying attention to it. So that makes me think the majority of people just want to see different stories and experiences. The thing that’s so interesting about the civil rights movement of the LGBTQ community, versus the racial civil rights movement of the 60s, is that queer people are born into your family, which forces us to face it. In recent years, numerous legislators have had to contend with their children coming out. How can they go and say their child doesn’t deserve marriage equality? And so it was passed. Also, when an American hero comes out as trans—that really pushes things forward.

I wonder where we would be in gay rights if AIDS hadn’t happened. Not only did we lose so many great artists and leaders in the community, but all of the resources had to go to screaming for help and taking care of each other.

In the trans community—which is related, but separate from LGBTQ in a lot of ways—trans people have fallen in and out of being accepted throughout humanity. Being trans is something that indigenous communities throughout time have upheld as a shamanistic trait. It’s only been a few hundred years in white society in which a trans person has been an unacceptable thing. We love Laverne Cox and Caitlyn Jenner, but 20 trans women of color have been murdered this year. I’m all for marriage equality, I’m happy that went through, but I’m kind of like—fuck getting married, can we save these lives?

My family—who didn’t want to talk about me being gay—is suddenly so interested in talking about trans people. I was on the show Transparent, and these old Jewish people are in it, which really helped my parents with understanding the show. I did a short documentary (which is part of a series of short documentaries) called “This Is Me,” produced by Wifey.TV. They were nominated for an Emmy. I star in one, and my family saw this. Suddenly, I’m getting phone calls from my sister, who has never talked about my queerness. Now, she’s asking me what I want my niece and nephew to call me—Aunt or Uncle. We’re having this conversation now.

Everybody, all of a sudden, decides that they have to be cool with it, because it’s not cool to not be cool with it, and then everybody just gets on board. These days several of my friends have kids, and six-year-olds totally understand trans people. They don’t get separated by boy’s lines and girl’s lines anymore. I’m going into more spaces that have gender-neutral bathrooms. Even for me, hearing a guy peeing in the stall next to me feels like a radical act. It’s not a radical act, but it feels so radical. We’re all just people peeing now.

There are all these new stories to tell. There’s a huge society of people that haven’t been telling their stories. We want to know what their stories are about. I mean, look at how many stories about gay couples and trans people are coming out in Hollywood this year. So many! Everybody is really into it. I mean, I’m already hearing people say things like, “Isn’t it enough already with all the gender stuff.” But this is the first year after 100 years of filmmaking history that these stories are starting to emerge. A lot of people have had enough with the same straight love story.

SB: Are there roles that you feel more comfortable with, or do you jump into all of them with an adventurous attitude?

MS: If the camera’s rolling, I’m there. I’m ready to perform. I’ll jump into anything. I’m lucky now that I’ve been given really fun stuff to play. I didn’t grow up like that. I’m a writer because I had to write my own stuff. I couldn’t get casting. I’ve always been like this. My mom got my ears pierced when I was one so people would stop calling me a “cute little boy.” I’ve been told by so many people that this was going to limit what I was able to do. But recently, I’ve realized it means I can do anything. I’m performing male and female all the time. What I love doing now—which horrifies a lot of other butch lesbians—is to wear a dress. I have a bunch of stuff coming out where I’m the ugly best friend, or I’m the prostitute, or whatever. That’s drag to me, but I can get into my femme side. I feel like an artist when I do that. It’s so powerful.

I always used to stick to comedy. Now, there are parts written where I’m playing a character closer to my own experience. That’s really challenging, and totally new.

SB: So, what kinds of projects are you working on at the moment, or in the near future?

MS: I’m finishing up shooting the second season of Transparent. I have a really cool, fun, scary role in that. I’m finishing writing a feature that I’m supposed to shoot next year. It’s called The Sangres. It’s a dark, comedic, anti-Western with queer themes that Devendra is writing the soundtrack for. It’s influenced by Bob Dylan and Sam Peckinpah. And the fucking desert. I’m doing anything people ask me to do. I starred in a webseries. I’ve been drawing a lot. Just creating my own content.

I’m doing embarrassing things all over town. If anyone has anything embarrassing for me to do, I’m there. If you want me to cry, I can do that too. I’m always on time, congenial, and I’m always sober on set.

SB: There’s definite progress being made in terms of acceptance and rights for those within the queer community, but is there an ideal destination and what does it look like to you?

MS: The part of me that came out in Kansas—the person who had to hide for so long—wants to say that the destination would be to not have physical violence done upon you because you are Other. The more optimistic thing to say would be that there would be no Other. Or rather, that we would all be Other. I see us opening up our gaze on gender, and seeing it as a broad spectrum. But I think that’s only one little domino to knock down. Okay so we stop seeing people of other genders as Other, when are we going to stop seeing people from different countries and religions as Other?

I would love to see a year in which people who have consistently been at the back of the line take a move to the front. I would love to see them take over in film and in art. Just for one year. Take the director and turn him into the PA—see what happens. That would be a good short-term goal. Just a year, just sit down, shut up and watch!