With her sophomore film, Celine Song confronts the harsh realities of finding love in the age of late capitalism.

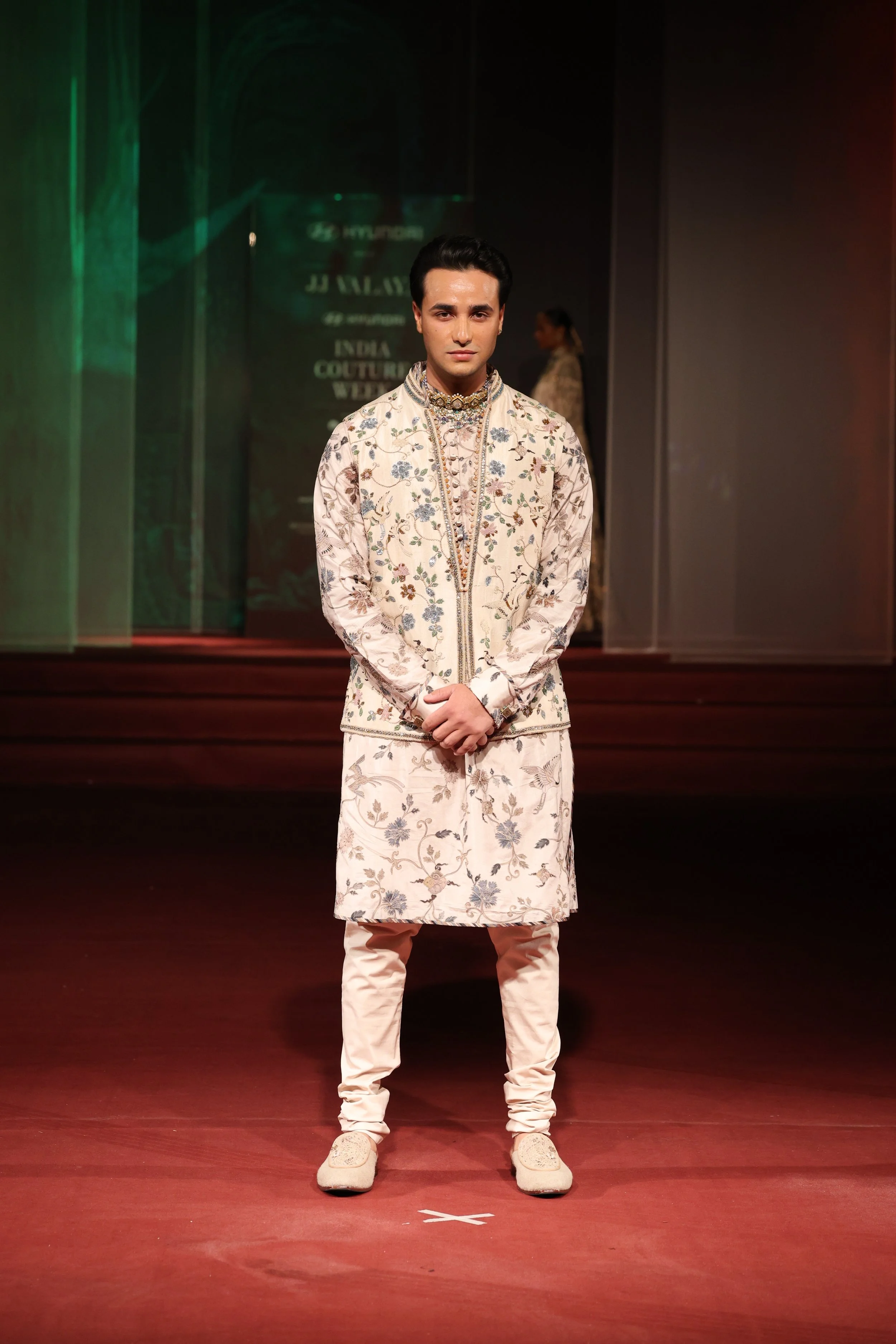

Lucy (Dakota Johnson) and Harry (Pedro Pascal) in Materialists.

A24

text by Kim Shveka

After her success with Past Lives (2023), at only thirty-six years old, Celine Song is back with Materialists, a self-proclaimed rom-com film. Here, the use of an aging genre serves as bait, only to reveal a somber and unflinching analysis of modern dating. In many ways, it looks and acts like a rom-com, but with a realness that challenges the genre. Unlike most romantic comedies—Hollywood’s once-beloved blockbusters, Materialists startles us with the terrifying unpredictability of authentic romantic connection. It does so with such bold intention that it forces you to re-evaluate your own moral barometer. It does stick to the rom-com tradition of being a bit quirky, but without ever softening its clear focus: the harsh reality of looking for love in an increasingly vapid society.

Instead of leaning on the cliché of romance as a battle of the sexes, Song presents dating as something far more unsettling: a stage where one’s self-worth is itemized and measured, where affection is dispensed, and where frank connection risks being reduced to trade. Through the eyes of Lucy, played by Dakota Johnson, love is a game of calculation. What is usually portrayed as a series of clever lines and happy accidents becomes a negotiation of value, often cruel and exposing, where emotions are fragile collateral to the forces of status, money, and appearance. To make this point explicit, Song threads price tags throughout the film, attaching literal numbers to everything from “acts of love” to Lucy’s makeup—the mere cost of admission to the neoliberal dating market.

The film begins with a cold open scene of a prehistoric couple exchanging a flower ring, marrying without even knowing what a wedding is. Immediately, you connect this spiritual, non-materialistic moment with the film’s title. With that unexpected artistic choice, Song sets the tone for the entire story, as we watch Lucy grappling between the primitive—her true love—and the present moment—her desire for comfort.

Lucy is a failed actress turned successful matchmaker in New York City. She is instantly revealed as the best at her job, though ironically incapable of finding her own match. At a wedding of a couple she paired, the bride has second thoughts and calls Lucy to her room. The bride admits she fears that she’s not marrying her fiancé out of love but because she likes how her sister is jealous of her. Lucy reflects for a mere second and answers: It’s because you deem him valuable. What may seem like a banal answer comprises the film’s central question of value in motion. Soon, Lucy meets the groom’s brother, Harry, played by Pedro Pascal, eyeing him as a potential client. He is what matchmakers call a ‘unicorn’ —a tall, wealthy, and handsome man. He’s that enduring mythic catch made exponentially rarefied by our current era. Of course, it doesn’t take long before his value to her shifts from potential client to mate; a subtle yet significant shift in the nature of their transaction. As they flirt, they are abruptly interrupted by John, a waiter who is quickly revealed to be her ex, played by Chris Evans. Over a quiet cigarette outside the venue, they let us into the depths of their long, complicated love story.

Lucy begins dating Harry, who takes her to fancy restaurants, sends her bouquets, makes pleasant conversation, and truly is the perfect gentleman. In Materialists, not a single emotion goes unacknowledged, and in what feels like the first time in cinema history, Harry is even seen paying the bill on-screen. Lucy even comments on how elegantly he does it, leaving no room for confusion that he is the provider, which leads to an honest conversation about her underlying insecurities. She sees herself as too old, too poor, with nothing to offer, such that she finds Harry’s interest in her bewildering. Yet Harry declares that he sees value in her, and through him, Lucy begins to detach from her analytical ways, surrendering carefully to her emotions.

While everything seems perfect between the two, Lucy can’t seem to shake her feelings for John, who is a thirty-seven-year-old struggling actor living with three roommates. In a flashback to their relationship, Lucy and John are driving to a restaurant for their anniversary, arguing over financial problems. It ends with Lucy saying, “It doesn’t work between us, not because we aren’t in love, but because we’re broke.” The line is brutal in its honesty, and it represents the most succinct summary of the film’s question at hand: In today’s world, is love enough? To answer this question, Song gives Lucy two choices whose compelling contrast mirrors her inner conflict very nicely without ever attributing much to the men’s personalities.

Lucy (Dakota Johnson) in Materialists

A24

At face value, the plot screams rom-com: two men, one woman, a choice must be made. But with its emotional intelligence and honesty, Materialists defies the genre’s tendency toward guaranteeing a fun watch. It was made to confront the way that financial security governs modern intimacy and to suggest that this is just one unfortunate product of a failing economic system. It lays bare the inherent contradictions that we think love is supposed to resolve. Wanting love does not mean rejecting security; wanting comfort does not mean giving up passion. Song captures this trope without hesitation. And yet, despite its harsh message, Materialists still carries a rhythm that feels light, offbeat, and witty. Rather than shying away from ugliness, she reinforces that it is a part of being human. Even the soundtrack reinforces this paradox: instead of popular songs, the film relies on mellow piano, almost elevator-like in tone, looping through each scene. The score builds tension by refusing to release it, heightening the strangeness and unease, while simultaneously laying a cushion for our eventual realizations.

The fact that Materialists was written by a young woman is evinced throughout the film, as if we’re viewing the world through the collective lens of a frank feminine experience while dating in the modern world. It’s volatile and fierce, deep and shallow, a beautifully rendered realm of inner conflict. Song’s perspective gives the film its pulse: she captures the contradictions of wanting both freedom and security, love and stability, romance and realism. Her voice carries an honesty that isn’t trying to universalize the female experience, but rather to present it in its full complexity with a vulnerability that makes the film feel alive. In only her sophomore film, Song reveals herself not just as a strong director, but as one with a voice entirely her own. Her vision feels deliberate yet alive, her choices inventive without ever being showy. She threads value, price, and desire together with a precision that feels effortless, like she’s bending the form of cinema to her will while keeping its meaning sharp and intact.

By making Lucy a matchmaker, Song cleverly refracts the dating-app culture of our time through a more timeless form. The algorithms of swipes and stats are concealed in the guise of “intuition,” but the effect is the same: relationships are matches, profiles, and data. And yet, because the device is matchmaking rather than apps, the film resists the inevitability of dating itself. Materialists is both of this moment and cleverly unattached to it.