Walking around New York Fashion Week: Men’s, you are likely to befriend other dudes that are as obsessed with fashion as you are. It makes you feel like a bit less of a weirdo. One such friend I made at this last round was Preston Douglas Boyer, a guy who looked a bit like a cross between a Hesher longhair and a teenage Supreme worshipper that was actually a Houston-based fashion designer who just released his first collection of motocross inspired and geometric printed line of garments back in February.

Boyer is something of a Hypebeast. You can watch videos of him on YouTube as a 14-year old giving his informed opinion on the latest drops of Jordan’s and luxury brand sneakers. That taste for luxury sneakers later translated towards clothes, and Boyer initially worked as a stylist for Houston and international musicians that would come from the city. Last year he took the plunge and started designing clothes that he wanted to wear, all while studying marketing at the University of Houston.

Also interesting is that his partner and brand equal is Harry Patterson, who is in charge of production for the brand. The guys are equally invested into the garments as they are into the production of the brand, indicative of kids who grew up in an era where image was everything and everywhere. Designers like Boyer are going to start appearing more in the industry. As opposed to the designers before them that found themselves influenced by Rei Kawakubo, Le Corbusier and Joy Division, we are about to see a lot of kids that have been mainlining Supreme and Nike for as long as they can remember. Read on for my conversation with the guys.

ADAM LEHRER: So yesterday you told me that you started the brand because you felt something was missing from fashion. What was that thing that you felt was missing?

PRESTON DOUGLAS: I really felt like functionality within luxury menswear was missing. You buy a jacket for $1,500, you buy a pair of jeans for $1,500, and you can have that for the rest of your life and as far as functionality goes our jacket has three jackets in one. You can style it 20 different ways. You can’t style a Saint Laurent bomber jacket like that.

LEHRER: You can’t even put it on unless you weigh less than 140 pounds (laughs).

PRESTON DOUGLAS: I want to change up the patterns. I love geometric patterns.

LEHRER: Yeah.

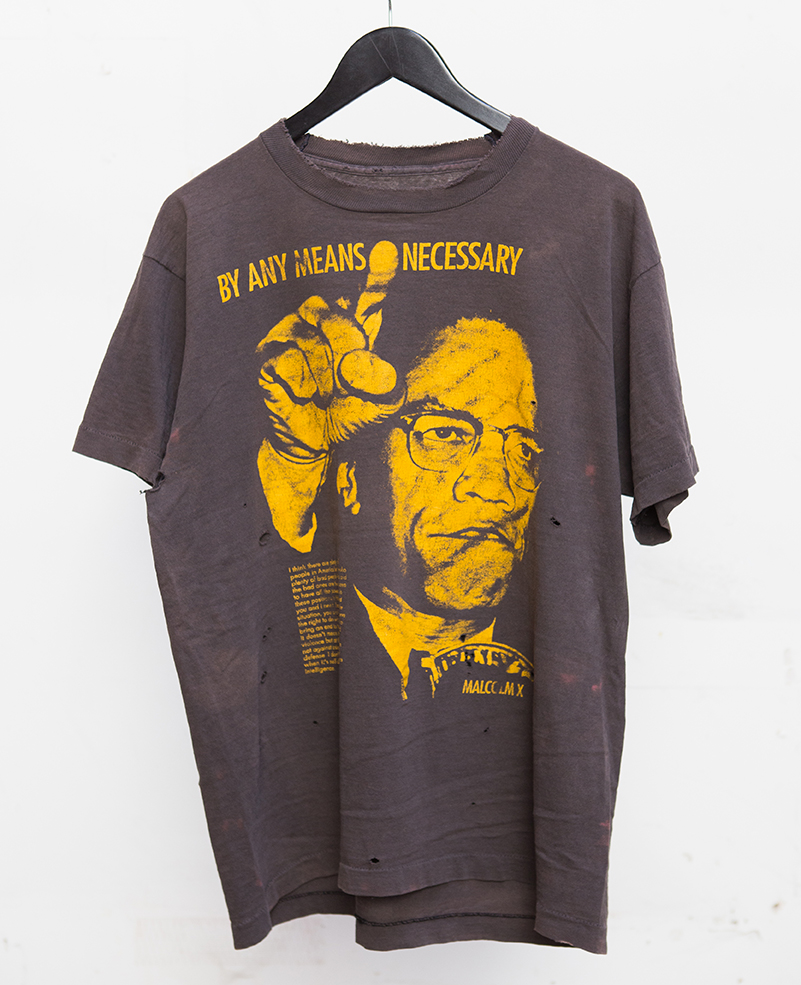

PRESTON DOUGLAS: Being a consumer for so long, starting with sneakers, I have an appreciation for color that I feel like a lot of menswear lacks. When I buy a piece and spend a thousand dollars on a jacket, I want that to be a piece that when I go out people are like, “What is that? Where did you get that? Who made that?” And then you tell them, "Preston Douglas."

LEHRER: So you feel that men’s fashion for a while now has been black, black, dark colors. So you want a larger pallet?

PRESTON DOUGLAS: Black is my favorite color but I want a larger palette… but tasteful. I love prints but if you’re just doing all black and all whites and grays and then you just put together some print shirts, I don’t like that as much as incorporating said print into a variety of pieces.

LEHRER: You mentioned you wanted Harry to tell the stories. What were the stories with these first few designs you came up with?

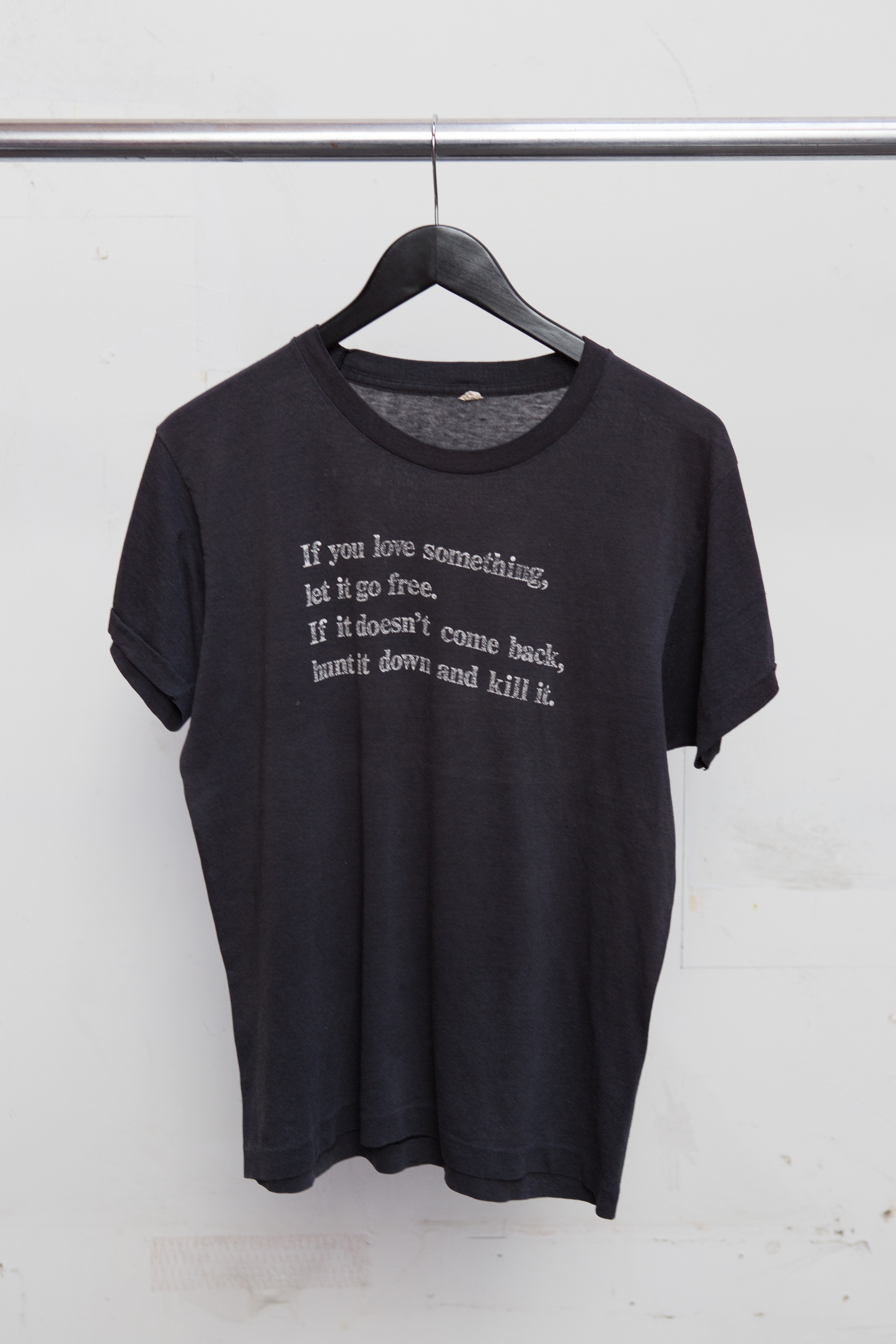

PRESTON DOUGLAS: Basically the collection’s called Calamity Serenity. The past two years of my life have been polar opposites. My life about two years ago was complete despair and chaos, I was lost. I didn’t know what I wanted to do with myself. I didn’t know how to function. So that’s the calamity, the black represents that chaos.

Then before I knew it I hit this point in my life where everything started to change. My life the year after is serenity. It’s a complete antithesis to calamity and you can see that in the colors. I feel like everyone has a point in their life where they’ve been through some really dark times - when you are ready to give up. I hope my story can help someone else.

LEHRER: Growing up, what designers made you think about apparel more than footwear for a brand?

PRESTON DOUGLAS: Christophe Decarnin. I remember looking at his look books. Really I got into luxury menswear because of luxury sneakers. Kris Van Assche for example. Ann Demeulemeester. Rick Owens. All these people had amazing sneakers. It’s all out there now with social media and Hypebeast and Highsnobiety.

LEHRER: Then socially too it’s become more accepted for dudes to be into fashion.

PRESTON DOUGLAS: Yeah! 8th, 9th grade when I started to get into sneakers and started my YouTube channel, I’d get called faggot or gay. Every single day all the time. I got major bullied for wearing colorful shoes, colorful Nikes. But I went to a private school so the only thing I could express myself with in terms of fashion were my shoes.

LEHRER: Exactly.

PRESTON DOUGLAS: I kind of created my own friend group and found my own path through creativity manifesting itself in a lot of different forms. First being sneakers; I had a sneaker resell business. I started a photography business. I started styling rappers and interviewing people when they came into Houston. Then with fashion, I felt like I’d been a consumer and seen enough to where I saw myself being able to fill a gap.

LEHRER: So you’ve always been entrepreneurial?

PRESTON DOUGLAS: Yeah I’m an entrepreneur first because nothing can happen without it.

LEHRER: As far as growth goes, what are your highest hopes for what the brand could be in a couple years?

PRESTON DOUGLAS: In a year I’d like to be showing in New York, possibly LA. I haven’t really been out there enough yet to see if my aesthetic and my brand fits with that culture and that lifestyle. There’s a lot of people in LA I look up to with regards to the fashion industry. So keeping it within the United States first and growing my local recognition and name and getting my manufacturing down.

LEHRER: So Harry, what’s your end of the brand?

HARRY PATTERSON: I was a production designer, I started out designing stages for concerts. Mainly live music, that’s what I thought I wanted to do for a while. I’ve done a lot of stuff making music or art. But while Preston is designing the clothing I want to be designing the set.

LEHRER: So it’s not just a one-man designing type thing? You guys are working in unison to bring two different ideas into one setting?

HARRY PATTERSON: Yeah I think that’s really important. This time he hit me up when the line was done and wanted me to DJ. I got him to take photos at one of my shows in Houston and he was like “I’ll give you a deal if you DJ my fashion show.” In December I called him to catch up and I ended up doing the production for it. I was skeptical at first, I had never worked in the fashion industry before but it worked out really well.

LEHRER: Were you interested in fashion or have you just gotten more into it now working with him?

HARRY PATTERSON: A little bit. Not as much as I am now. I never thought I’d be working in the fashion industry.

LEHRER: I feel like a lot of creative people just happen to end up in it in one way or another.

PRESTON DOUGLAS: Yeah! But the show in Houston was a really cool opportunity. I’m really glad Harry was involved because there was talk of moving Houston Fashion Week to the next level.

HARRY PATTERSON: I actually thought that was what fashion week would be like when I went. I was like “ehh I’ve seen this in the galleria before,” this is going to be a bunch of clothes I’d wear to church. So it surprised me. In the past three days I’ve met more people in the fashion industry than I know in the music industry. It’s nice it’s smaller because it’s more of a collaborative feel.

LEHRER: Yeah I get that.

HARRY PATTERSON: It’s harder to get that vibe with people in music.

Shop the Preston Douglas Calamity/Serenity collection here. Text and interview by Adam Lehrer. Photographs by Clay Rodriguez. Follow Autre on Instagram: @AUTREMAGAZINE