V presents...An Interview with Ad Agency Creative Director and Multi-media Artist Graham Fink

I first met Graham Fink in London in 2006. At the time, I was looking for a new job and my recruitment agency wouldn't send me on this interview: assistant to the Creative Director at M&C Saatchi. It sounded exciting, so since the agency was being so unhelpful, I set out to directly contact said creative director myself. Easy task. I made sure to point out in my email that the recruitment agency didn't want to send me to see him. Within 30 minutes, we had set up a meeting for the very next day, late afternoon. I met Graham at his offices on Golden Square... I had no idea what to expect, and he was everything I shouldn't have expected. I remember being pretty gauche in my interview and dropped the word 'creative' way too many times for the 'admin position'. I didn't get the job, but I kept in touch with Graham over the years. He has never stopped being a great source of inspiration for me. He currently holds the position of Chief Creative Director of Ogilvy in Shanghai.

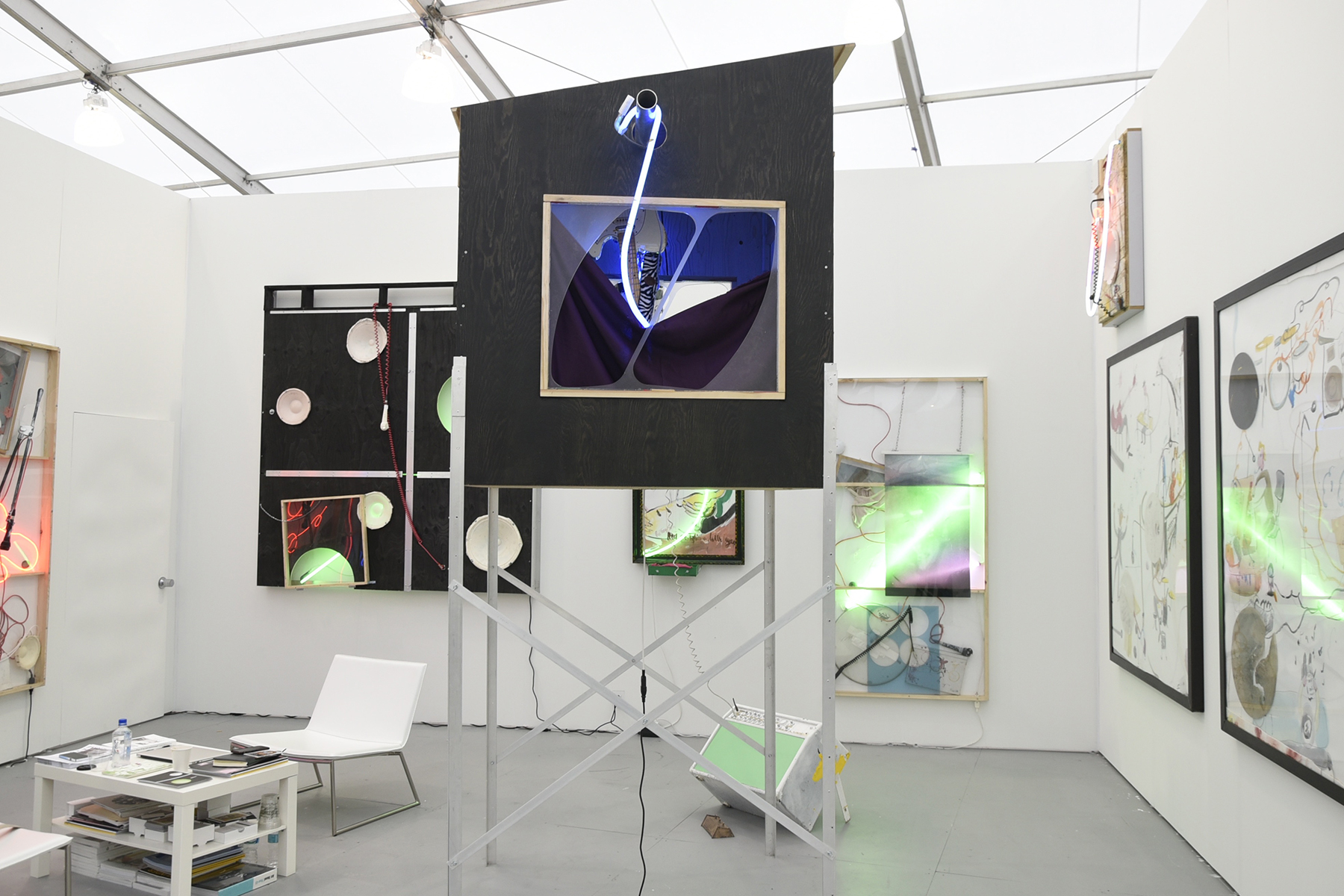

It has been so exciting to see him make the natural but sometimes difficult transition: from "Ad' agency Creative Director" to "Multimedia Artist". Really it is all the same, only the title changes. Graham's new solo photographic show entitled "Ballads of Shanghai" opened at Riflemaker in Soho, in London on February 1st. I took this opportunity to interview him for Autre Magazine.

VIRGINIE PICOT: You have been based in Shanghai for 5 years. What impact has your move to Shanghai had on your work?

GRAHAM FINK: Moving to China had a huge impact on me from day one. The sheer scale of the country and the different way the Chinese look at things. Both visually and philosophically. It also taught me that everything I knew, was of no use to me whatsoever.

PICOT: China has gone through and is still going through a big transformation culturally, economically and socially. Your show is about the rapidly changing landscape of Urban China. How has this transformation affected you as an artist during those 5 years?

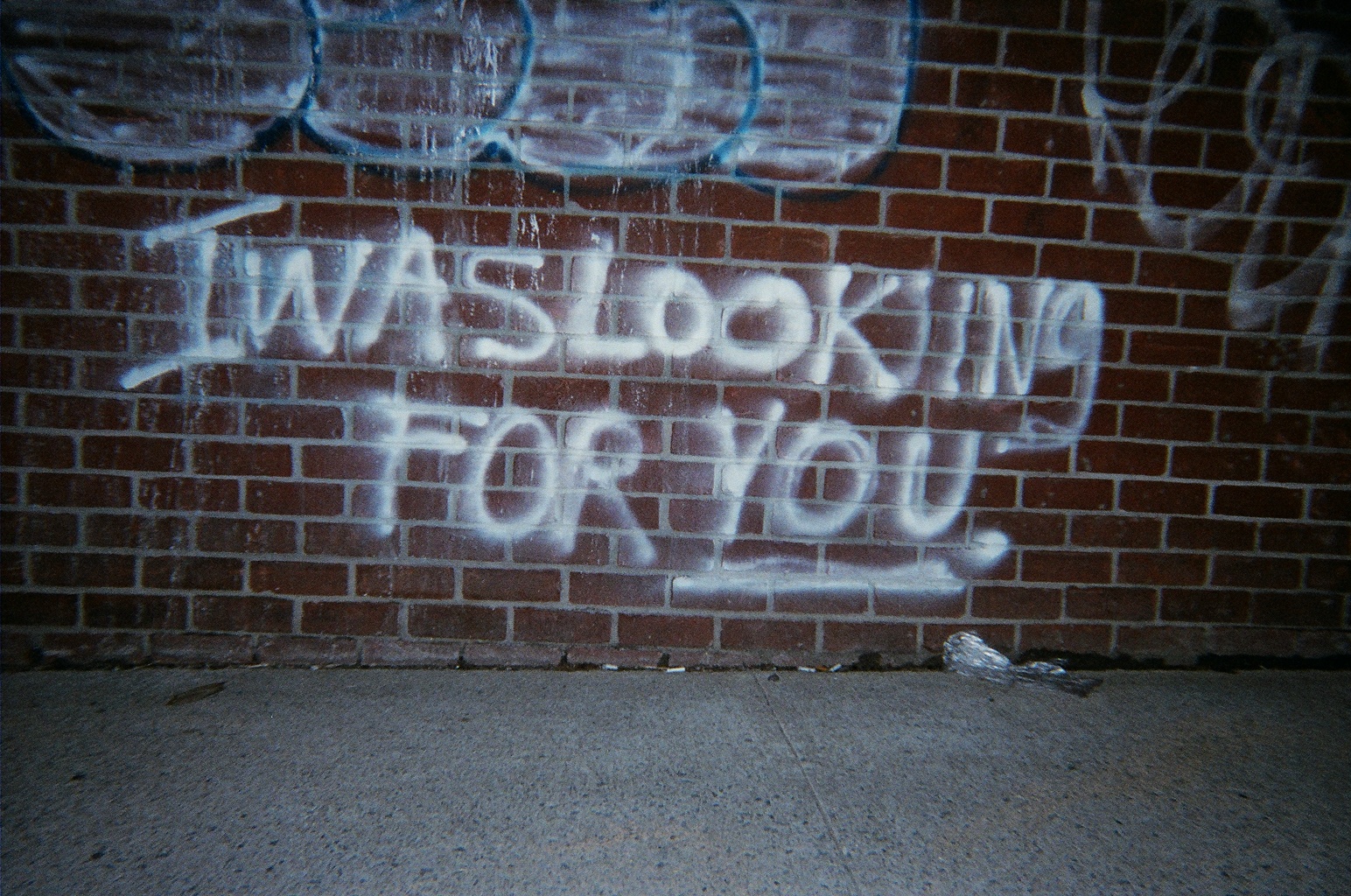

FINK: China changes herself faster than David Bowie’s characters. But like Bowie, the country is on a voyage of self-discovery. After the Cultural Revolution, China was so far behind the West that it had to catch up fast. And I think that’s why there is so much copying going on here, because that’s the fastest way to catch up. But now, many creative people in China - artists especially - are going back to their deep roots. Finding the latent creativity in their DNA. Their true voice. What they really stand for. For me, as an artist from overseas, I am working with the unfamiliar. I like to get out of my comfort zone and see new things around me that I don’t understand. Yet. But I am also confident in my own DNA and instinctively trust it in my work to mash East and West cultures together.

PICOT: Can you tell us more about this show? Talk us through the original idea through to the process and execution.

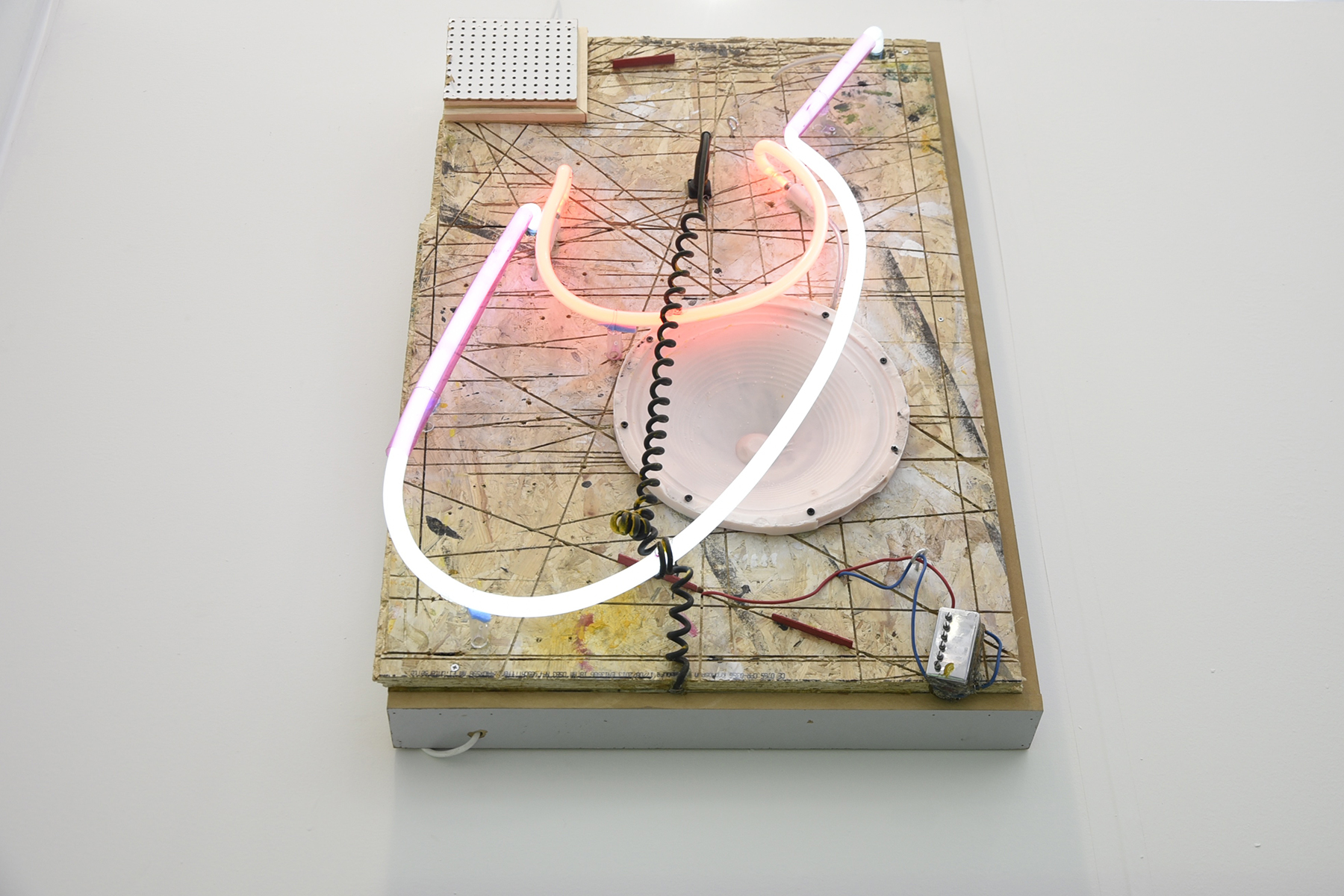

FINK: Well, as a kid, I’ve always been fascinated by derelict buildings, empty shells, rubbish dumps and so on. My parents lived on a farm with thousands of acres all around us and everyday I went exploring. I came across all sorts of ‘secret places’ and found things that I'd never seen before. So I’m probably at my happiest when scrambling around similar places today. And now I have a camera, it allows me to capture the things I see. It’s a bit like discovering treasure. As with the ‘faces’ I have taken thousands of images. But it’s when they are seen together that powerful stories emerge. For this exhibition I have used recycled wood to make the frames. So even that has a different past. I wanted a kind of new and old feeling to the prints. So after much experimenting, I printed them onto a beautiful matte art paper and then painted certain areas of the photographs in a high gloss varnish. So as you walk past them, they catch the light and they change.

PICOT: Faces are a common denominator in your work. In your print on marbles "Nomads" series as well as your "Drawing with my Eyes" series, what is behind this fascination, or perhaps obsession with faces, and how do they fit in this show?

FINK: I’m a Pareidoliaist. I see faces in everything. Cracks in walls, mud splattered cars, flaking paint on doorways. These apparitions continue to grow and the spirits seem to follow me everywhere. In this show the faces take a back seat, but they are still there if you look for them. It has become an obsession and over the years I’ve taken thousands of these "ghosts." Paul Verlaine said best: “L’image poétique devrait être plus vague et plus soluble dans l’air.”

PICOT: You have worked across various media, won countless awards... How do you keep your ideas fresh and how do you keep inspired?

FINK: For me, it's important to stay fresh by experiencing new things, going to new places. Some people want to be cool, well, I think that being ‘cool’ stops you from finding new things. If you’re ‘cool’, you may not listen to a particular type of music, or you wouldn’t be seen dead in certain places. That’s when you get stale. When I came to China, most of my friends thought I was mad. And it certainly was a massive culture shock. But it’s amazing how fast your brain normalizes everything. Luckily, China is a big place with many subcultures. I see things everyday that leave indelible markings on my mind.

PICOT: Who has the biggest influence on you as an artist?

FINK: That’s impossible to answer as there are so many, I mentioned one earlier, and now that I’m in China, I discover many new ones that I’ve never heard of before. But every time I see Frank Auerbach’s work, I get excited. And of course no one could be more obsessive than him.

PICOT: How is your work as Chief Creative Director for Ogilvy China feeding into your work as an artist, and vice versa?

FINK: It’s funny, but I often get asked that question. As I see it, both Art and Advertising require acts of creativity. I never say, well today I am doing advertising so I’ll put my advertising head on, or the next day, now where did I leave my artist head. I think it’s more about you as a human being. How you approach something. The art I do is very conceptual, and so is working on an ad campaign. It always starts with an idea.

PICOT: What art do you most identify with and why?

FINK: I love art that looks free. Where you're not aware of the hand of the artist. In China there are 5 main styles of calligraphy, but my favourite is the cursive style. Often the brush never leaves the paper, and so the characters merge into one another. It’s not particularly legible to the average person, but you can feel it more than you need to read it.

PICOT: Art on social media vs. social media art... Are social media platforms the best modern advertising space for art or does the art get diluted in that space? Do you have a social media strategy?

FINK: The best social media art isn’t necessarily made for social media. I was intrigued by Richard Prince's exhibition of Instagram images complete with Likes. They were hanging in a gallery, but were also going crazy on social media. This gave it a kind of double meaning, which of course I’m sure he intended. The most interesting art has always been talked about and shared, either by a tweet or word of mouth. And word of mouth has always been the best advertising. As for my own social media strategy, I think it’s important to embrace what is out there and experiment. This interview has been another experiment.

Ballads of Shanghai runs until February 14, 2016 at Riflemaker, 79 Beak St, London W1F 9SU. See more of Graham Fink's work here, and follow his Instagram to keep up with the experiment. Text and interview by Virginie Picot. This is the first in a series of interviews V will conduct with individuals in the creative fields. Follow Autre on Instagram: @AUTREMAGAZINE

Write here...