Introduction by Raed Yassin

Interview by Oliver Kupper

The Swinging Sixties and Super Seventies were a time of pleasure and paradise in Beirut, when it was the designated erotic capital of the Arab world. Dubbed “The Paris of the Middle East,” the city quickly became the top tourist destination in the region, attracting movie stars and pop singers. Beirut boasted many casinos, nightclubs and cabarets filled with flashy dancers and playgirls, ready to serve the sensual whims of incoming celebrities, businessmen, and royal Gulf Arabs.

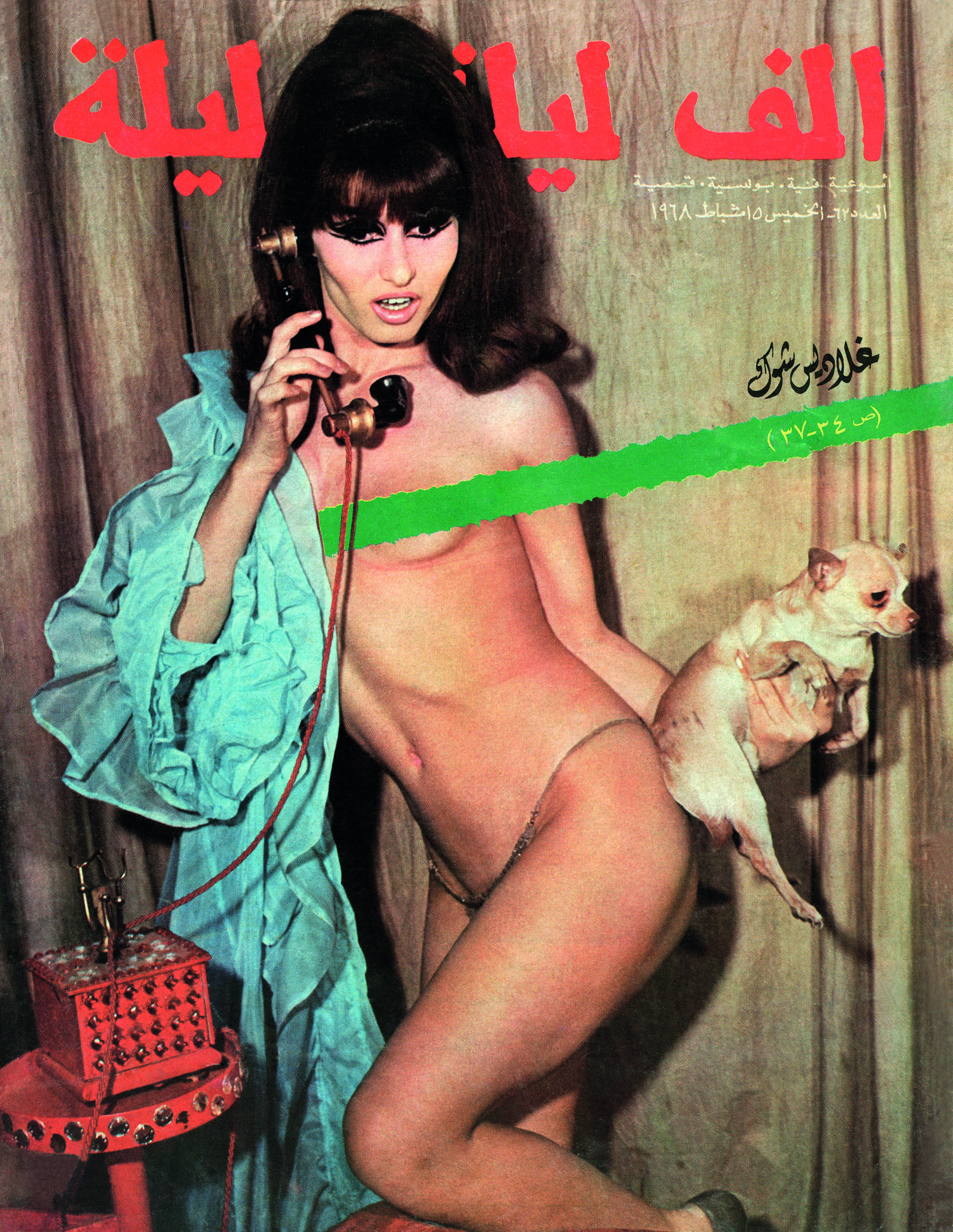

In those years, you could come across sexy films and magazines everywhere, magazines like Sex, Arabic Playboy, Furnished Apartments For Rent, Stars Lights, The Camera, Cinema Wonders, and Alf Layla wa Layla (A Thousand and One Nights).

The owner of the Shahrazad nightclub, Mr. F., had an idea to start an erotic magazine to promote the girls working in the club. So he published Alf Layla wa Layla. Little did he know that the magazine would soon become a huge hit, as it was the only one featuring local Beiruti strippers, who would soon be showered in unending fame and desire while they adorned its shiny covers.

In no time Mr. F. started to abuse his newfound success by using his girls to spy on customers, collecting scandalous information for future blackmail and bribes. Alf Layla wa Layla transformed into a dark source of power, and at one point Mr. F. even became an agent for the notorious “Second Office” of the Lebanese intelligence, operating his club as a honey trap for actors, singers and politicians alike.

One of the regulars was Prince Khalid Bin Saud: a Saudi Arabian royal playboy who loved to indulge in the fame and glamour of the time. Mr. F. acted as his pimp and drug dealer in Beirut, facilitating all of the Prince’s fantasies. They became very close to a degree that Mr. F. convinced him to publish stories of his lusty escapades in the magazine. The Prince agreed, divulging many sexy details to Mr. F.’s eager ears. In one interview, he admitted that he fell in love with a stripper at the club named Gladys Shock. These diaries immediately exploded into one giant scandal heard all around the city, and eventually traveled to the Prince’s homeland, where it was deemed highly unwelcome news. The Lebanese authorities were rattled, they couldn’t indict the Prince because he was untouchable, so they decided to hone in on Mr. F. instead.

Suddenly, the girls who were featured in the Prince’s sexy stories started to disappear, one after the other. Strange stories about them committing suicide emerged. At the same time, a high price was placed on Mr. F.’s head. He stayed in hiding for a while, leaving behind the glitzy Beirut nightlife and his beloved magazine. Later, he managed to escape to Saudi Arabia where Prince Khalid had promised to protect him.

That was the end of Alf layla wa Layla.

OLIVER MAXWELL KUPPER: What’s the current climate right now in Lebanon - both politically and socially – it seems like your work is a response to the cultural shock wave that reverberates from Beirut, which is a lot more metropolitan of a city than people imagine?

RAED YASSIN: Because of the mix of capitalism, tourism and religious diversity, Beirut has always been a cosmopolitan city, especially when compared to its surroundings. Its strategic location also helps in this regard. But both politically and socially, it could not be more chaotic or unpleasant today than days past. Society is drowned in alcohol, drugs, prostitution, weapons trade and social media gossip. Politically, it’s almost silly how politicians openly manipulate their power to divvy up and steal the country’s resources. Both political opponents and allies are sucking up every last drop of what wealth remains here like there’s no tomorrow.

Growing up in Beirut - during such an extremely turbulent time - are there any specific memories that have impacted your work?

I have two very memorable moments while growing up that impacted me a lot. The first was when my father threatened me with a red hot pepper for using the VCR player like a keyboard (and destroying it). Another was when my brother caught me peeping over his copy of Bravo Magazine, while I was fantasizing about the naked girls featured in the centerfold.

What was your first introduction to art - did you have access or a means to see art outside of the Middle Eastern context?

My first introduction to art was in my uncle’s garden, he was a trash collector. He used to assemble many different objects in sculptural forms. He didn’t know that he was an artist. But those shapes, they struck me in a way.

Another time I thought I saw a large-scale artwork outside the Lebanese context was when I was lying on my back in south Lebanon at night, and I started to see huge glowing lamps in the sky. I feel that was my first encounter with a light installation. I discovered later that this was actually an Israeli warplane throwing thermal detection balloons.

What do your parents do - do they support you as an artist or have they supported your ambitions as an artist?

When I was born, my father was a retired fashion designer. He hated that world, because of the long days of work with little or no return. My mother had always supported me going to the conservatorium and studying music when I was a teenager. She didn’t object to my artistic inclinations, but it's safe to say that she was concerned.

You are also a musician – does it help to create a soundtrack for your work or exhibitions when you are making the work?

It depends on the project. Most of my films are silent. I usually prefer to work on music and art projects separately, sometimes they may intersect, but it's a rare occurrence in my practice.

One theme that you explore a lot is human desire – what is it about human desire that is so enticing?

Desire itself is enticing. It is the energy that runs the engine of humanity.

Your new series "Sex, Spies, and the Suicide Dancer" is very erotic – growing up in Beirut, where did you get your hands on erotic materials?

In the late sixties, tourism was really flourishing in Lebanon. The ‘supporting acts’ of this industry also started to really develop, places such as cabarets, nightclubs, and brothels could be found everywhere. Popular media also wanted in on the action, so erotic magazines got into distribution too. Beirut then kind of became the erotic capital of the Arab world for a while.

I would be remiss not to mention the overwhelming wave of Islamophobia sweeping over the Western world, especially now that Trump is in office, what are your thoughts on that?

What really interests me is what comes next. Phobias are like desires, also another type of an engine for power to rule.

I think it would be interesting to install your Islamic writing series in shop windows throughout the American South - do you think we need to take a brand new radical approach to combating Islamophobia?

Why don’t you curate this project?

Another neon series, "Shine Bright Like A Diamond," really sticks it to the art world, do you think the art world needs to stop thinking of itself as the center of the artistic universe?

It's a vicious cycle that consists of many different factors that feed this unhealthy situation. Everybody is responsible, as it seems now that art is not protesting, its just being used to feed the greedy.

What is one of the greatest challenges as an artist dealing with the themes that you are trying to tackle?

Chopping onions for lunch.

•