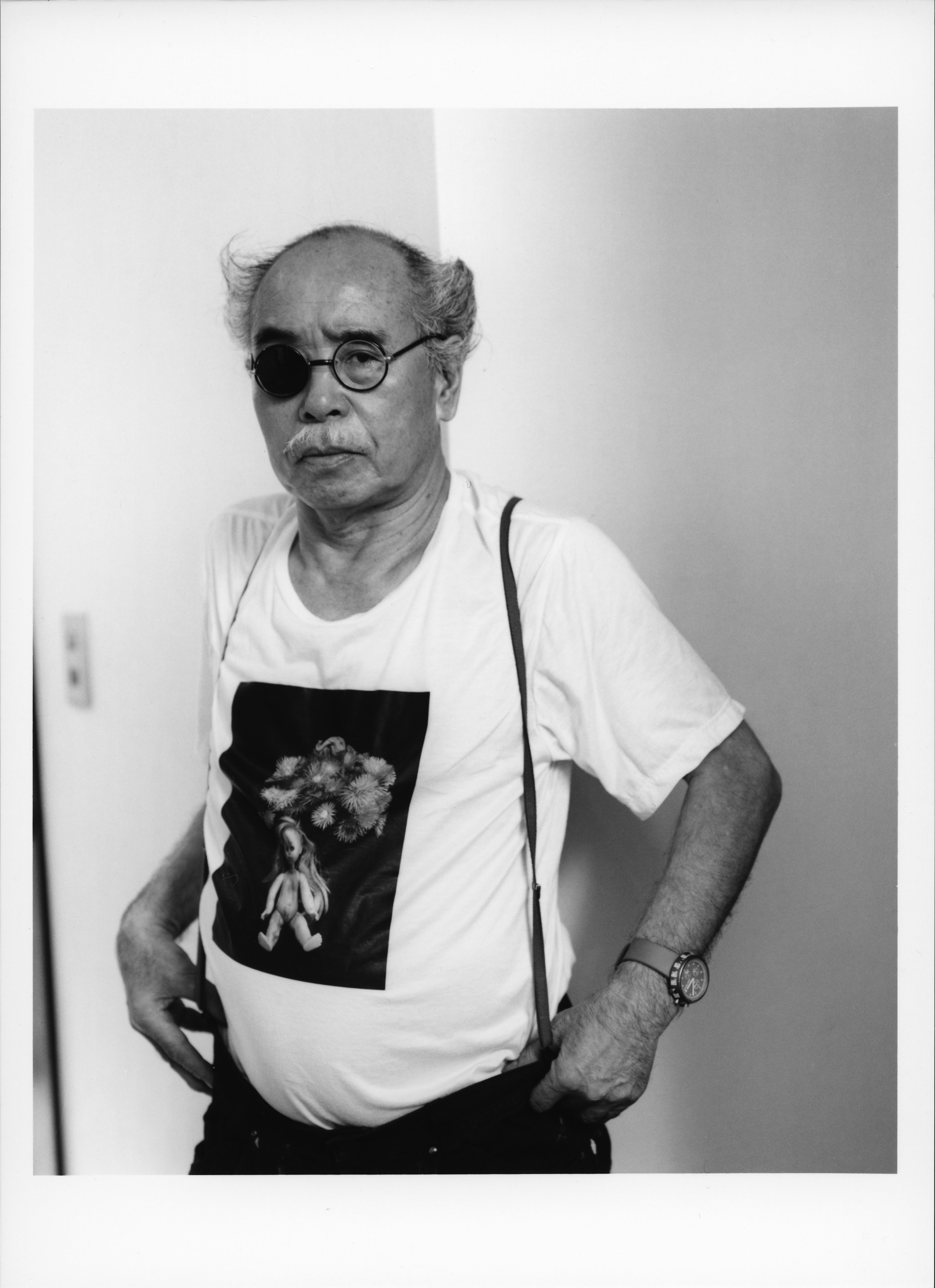

text and interview by Oliver Maxwell Kupper

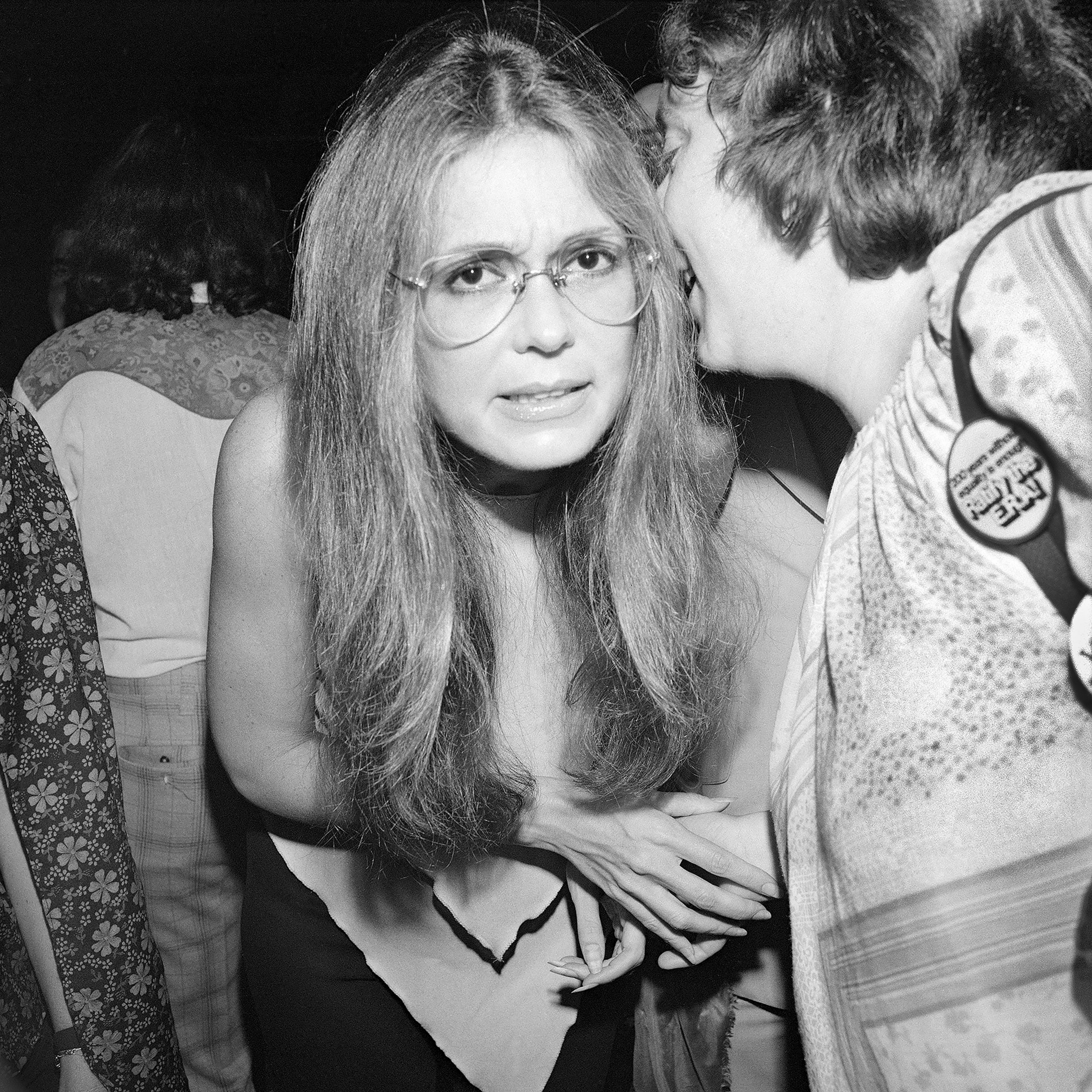

portrait by Bil Brown

When legendary photographer, William Eggleston, whiskey on the rocks clutched in hand, is telling you a story about Dennis Hopper saving him from falling off a 1000-foot ledge at the Continental Divide, and then asks you to stay for Chinese food, it's hard to say no. What else are you going to do on a Tuesday night in Memphis?

In Memphis, you learn about romantic and tragic things: The last song Elvis ever played before dying was "Blue Eyes Crying In The Rain" on his upright piano in the over air-conditioned racquetball courts at Graceland. In Memphis, the cicadas grind like jammed gears in flooded engines. On a dime, the sky can turn from sunlight to shade, like a sheet pulled over a half-living corpse, slowed to a dull kind of subsistence by the tepid humidity. This is the ecosystem, the hallowed Southern environment where William Eggleston's most well known work was born and gave the world a glimpse of its hard edges, saturated colors and sad geometries. If you look closer at his work, you are looking at a microcosm within a microcosm, the moments where the mind drifts and imagines mortal uncertainties - the fragmented glow or nuclei of sunlight reflected through a glass of Coke on an airplane, a girl laying on the grass zonked out on Quaaludes, or the tailfin of a Cadillac and some kind of unaware Americana on the horizon. But, if you look closer still, you will see hidden things, secret things, lost perspectives, living shadows, forlorn personage, but always on the periphery or just under the surface. Indeed, his photographs are very plainly obvious, but there is a certain kind of gossamer stillness that is poetic and serene, and reminds you that life's simple details, the ones that are oft overlooked, are the most important ones.

I’ve wanted to sit down with Eggleston for a few years now, and sit we did, in his Memphis apartment – crowded with a looming Bösendorfer grand piano in one room and gizmos and gadgets in another. Eggleston has always been obsessed with mechanics and the way things work – lately, his new obsession is quantum physics. Over cigarettes and the intermittent break to play piano we talk about everything from classical music to photography to the films of David Lynch. Our interview ended after day turned to night and there was no more whiskey.

Oliver Kupper: Do you enjoy classical music?

William Eggleston: Quite a bit. Mostly. My hero is [Johann Sebastian] Bach.

Do you listen to rock & roll music living in Memphis?

There’s not much around Memphis right now. I like all kinds of music.

You grew up with your maternal grandfather, he was an amateur photographer?

My grandfather? He did a little bit.

And did you learn about photography from him, or were you first introduced to photography through him at all?

No, most of the things he did long before I was around. Most of the things he did were of our family.

I saw a few portraits maybe he took of you when you were really small. Was that in Sumner, Mississippi?

Mmhmm.

What was it like growing up there?

The whole family grew cotton and it still goes on.

You didn’t want to go into the agriculture trade?

No, well there’s not much to do. Running a plantation – that just gets kind of boring, sitting around watching cotton grow. It’s not too interesting.

Of course, so you turned to more artistic pursuits. Classical music and photography.

Yeah, I’ve played the piano since I was about four years old.

And you play piano every day?

Yes, and the night too.

And you talk about Cartier-Bresson having a big influence on your work.

Yeah, I still think the world of him. He was one of the greats.

When did you first discover his work?

I suppose around the 50s. His photographs were all black and white and he worked in black and white for a while.

So how old were you at that point?

Oh, I had a best friend in prep school, we went to Vanderbilt together in Nashville and he got me interested in his work, and this was 1957.

I wanted to talk about another photographer that I’ve always sort of loved and reminds me a little bit of you because he started taking pictures of his friends and family. His surroundings. His name is Jacques Henri Lartigue, do you know his work?

Oh yeah, Lartigue I know his work.

Yeah, there’s a lot of kindred similarities between his upbringing and also his introduction to photography that is really interesting.

We never met, but I know his work.

I read somewhere that you were given a Brownie at ten years old to shoot with, and he was given his first camera at seven years old. Did you study his color photography, because he took a lot of color photography too.

I don’t have any around here right now, but in the other house, I have his books.

John Szarkowski, the curator at MOMA New York who put on your first show, he showed Lartigue’s work a couple years before your show actually. I think he saw something too, which I think is really interesting.

Yeah, me and John were very close. He died a couple years ago. He would show me a lot of things I didn’t know about. We spent lots of time together when I was in New York.

Did he teach you a lot about photography or the history of photography?

I suppose.

And when you first showed those color slides, what was his initial reaction? What was your reaction to showing your work for the first time? Did you feel hesitant at first?

We never much talked about it. I was quite happy to show it at MOMA, a good place to show it.

And that show got a lot of really interesting reactions. Because I think people were confused about fine art photography in general, not just color photography, but fine art.

Yeah, it was something, photography as fine art had to be in black and white – primarily large negatives. And that didn’t much interest me.

And one of the critics was Ansel Adams.

I didn’t care for his work to begin with.

When you first started taking pictures you were largely self-taught, technically speaking. Was it difficult to get the exposure right, did you have sort of a hard time clicking into what you were doing...or you latched onto it pretty quickly?

At first I had to use a meter, I don’t really anymore. Film is very forgiving now.

Can you remember those first few pictures that you took with the Leica camera? Do you remember that experience? What that felt like?

No, but I was happy with the results. There weren’t really many other cameras out besides Leicas that I could use.

Are there fine artists outside of photography that inspire you?

Lucian Freud was a friend, he died too. He does great paintings. I was in London and I saw one of his last shows. I think when I saw that last show, it was probably right before he died but it was some time ago in London.

So, speaking of legends, I want to talk about your meeting with Cartier-Bresson for a second. You got to meet him once, right?

Yeah, we were sort of friends. He was absolutely not interested in color.

Do you believe in photographic masterpiece?

Not much.

They’re all masterpieces.

I really don’t have any favorites,

Because there is one work by you that sort of sticks out – the glass on the airplane, I know that a lot of people talk about that one. What was the context of taking that photo?

Oh, that was an ex-girlfriend of mine having a Coke, I think we were coming from Dallas to New Orleans.

It’s a really gorgeous photograph.

Thank you, I liked it too.

How did you come up with using your particular process or did someone mention it to you?

Do you mean by that, the dye transfer? I saw it first when, I forgot where, but it was commercial advertising pictures and fashion pictures. The process was really so good that I should use it for my own work and still do.

And C prints but not as much; you try to stick with dye-transfer.

I use both. I use dye transfer and pigment. But the transfers are really, well whoever is doing the lab work, exposes them through three primary filters, black and white, big negatives of the exact sizes of what it’s going to be.

Interesting.

And it’s just...I’ve been around and watched them be made but I’ve never tried to do it. They’re using black and white film, true to the size of the final print. 16x20 inch negatives, three negatives of that same size. It’s really just black and white through filters.

Right, which is why your images are sharper.

Well the filters are there to separate, rather than to mix together, all of the colors in the picture. The lab technician really had to know what they’re doing.

Winston was saying that you’ve been studying quantum physics. What turned you on to that?

That’s right. I can’t figure out how to answer that, I don’t know. It’s just physics and then quantum is, of course, close to physics but it’s, I don’t know how to put it, but it’s...the end result is what probably will happen, not what accurately will happen, but will probably.

Do you apply those thoughts to photography ever?

I don’t know.

There’s something about capturing a moment that was moving before, on film, you know?

That could be related in some way. It’s like Mr. Einstein once said: no such thing exists as a point absolutely in one place. That’s kind of what quantum is, the probably but not exactly, if that makes sense. I feel probably close to quantum because I think it’s related to my own work, because whatever that picture is, it’s what I thought probably should be there. Not anything exact.

One of the documentaries that these people have done, at the end of one, you were talking about a dream and then waking up and then the dream being gone completely...

That happens so many times every day. I’m dreaming about music and I’ll get up and rush to the piano...(snaps) Gone.

Wow, full compositions and such?

Yeah, every note, it’s just so beautiful in the dream and then I sit down and face those 88 keys, and I don’t know which one to push.

That’s really interesting. Do you ever think about music when you’re shooting? Is music related to shooting at all?

I think that’s probably true, there’s some connection. Whatever that is, I wouldn’t even begin to talk about it.

There’s a mysterious aspect to how music relates to making pictures.

I look at it that way a great deal, probably. Working in quantum physics and theories about pictures – it’s not a bit unlike a symphony or let’s say a set of symphonies or sonatas.

I mean the Democratic Forest, it is like a symphony in a way; it is like a multiple part symphony.

I think of it that way.

It seems, artistically, you’re driven by pure intuition and you don’t over-think things, and you leave all of that to the quantum physics and the mechanics.

That’s right.