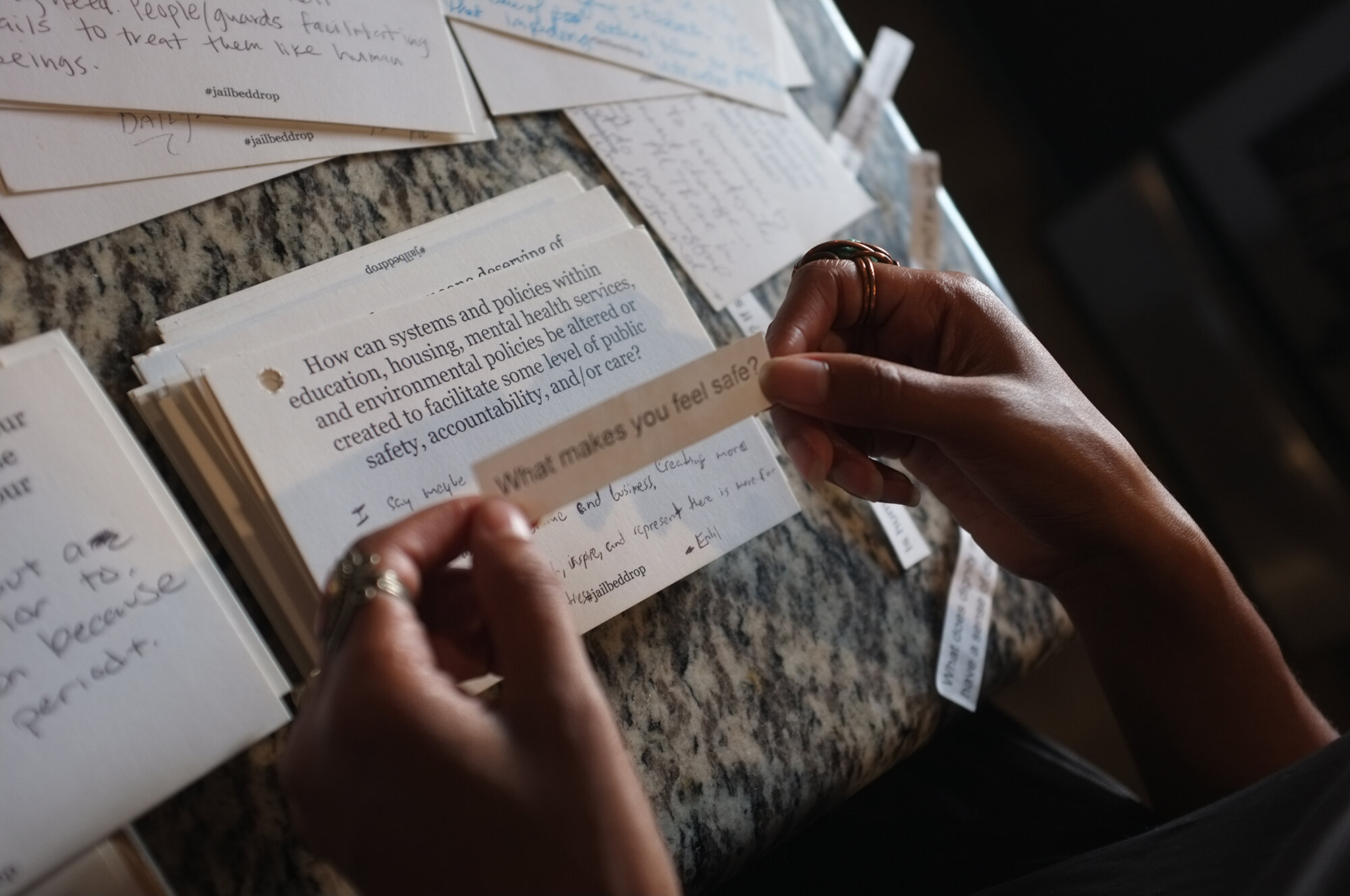

interview by Lara Monro

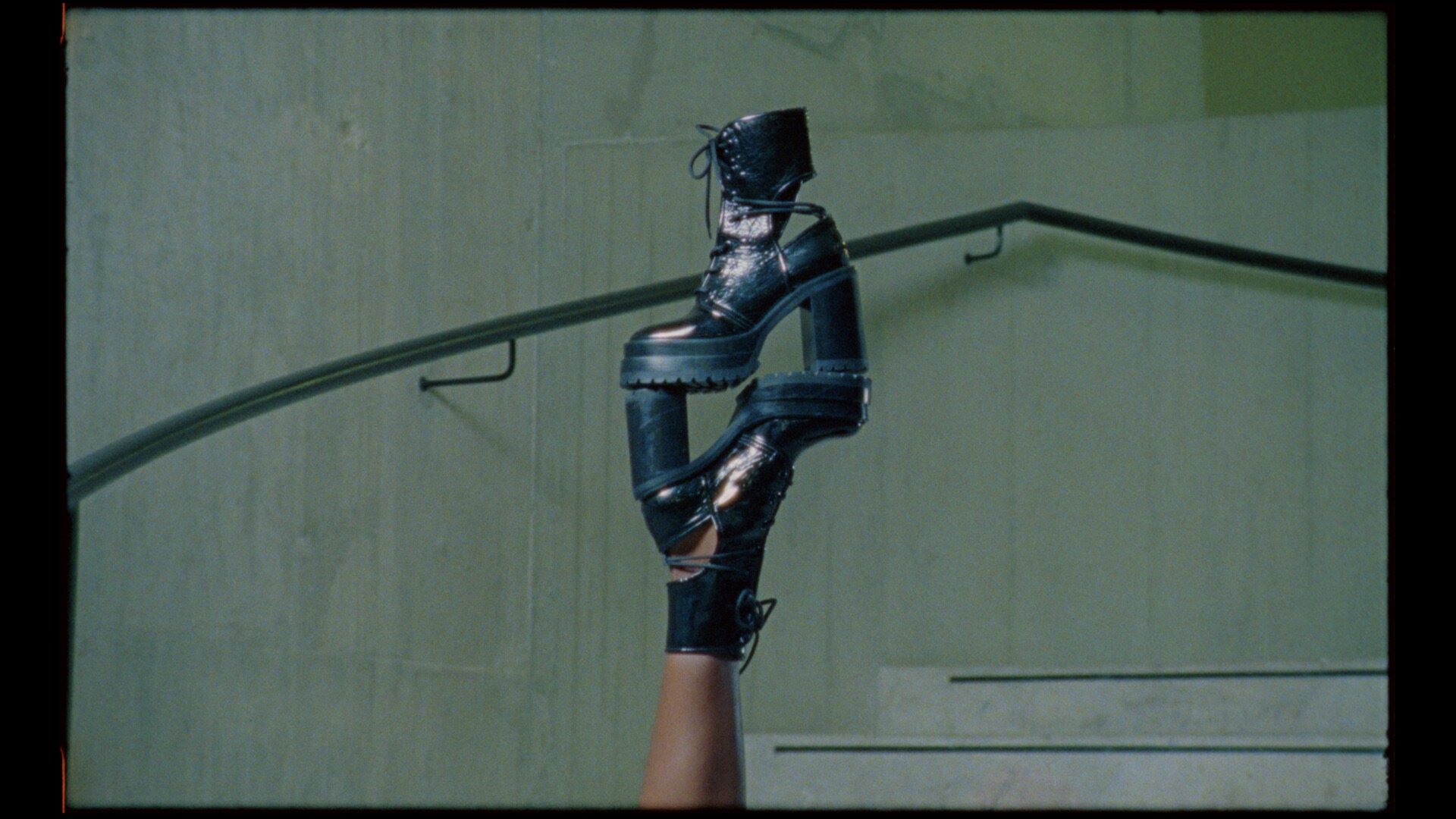

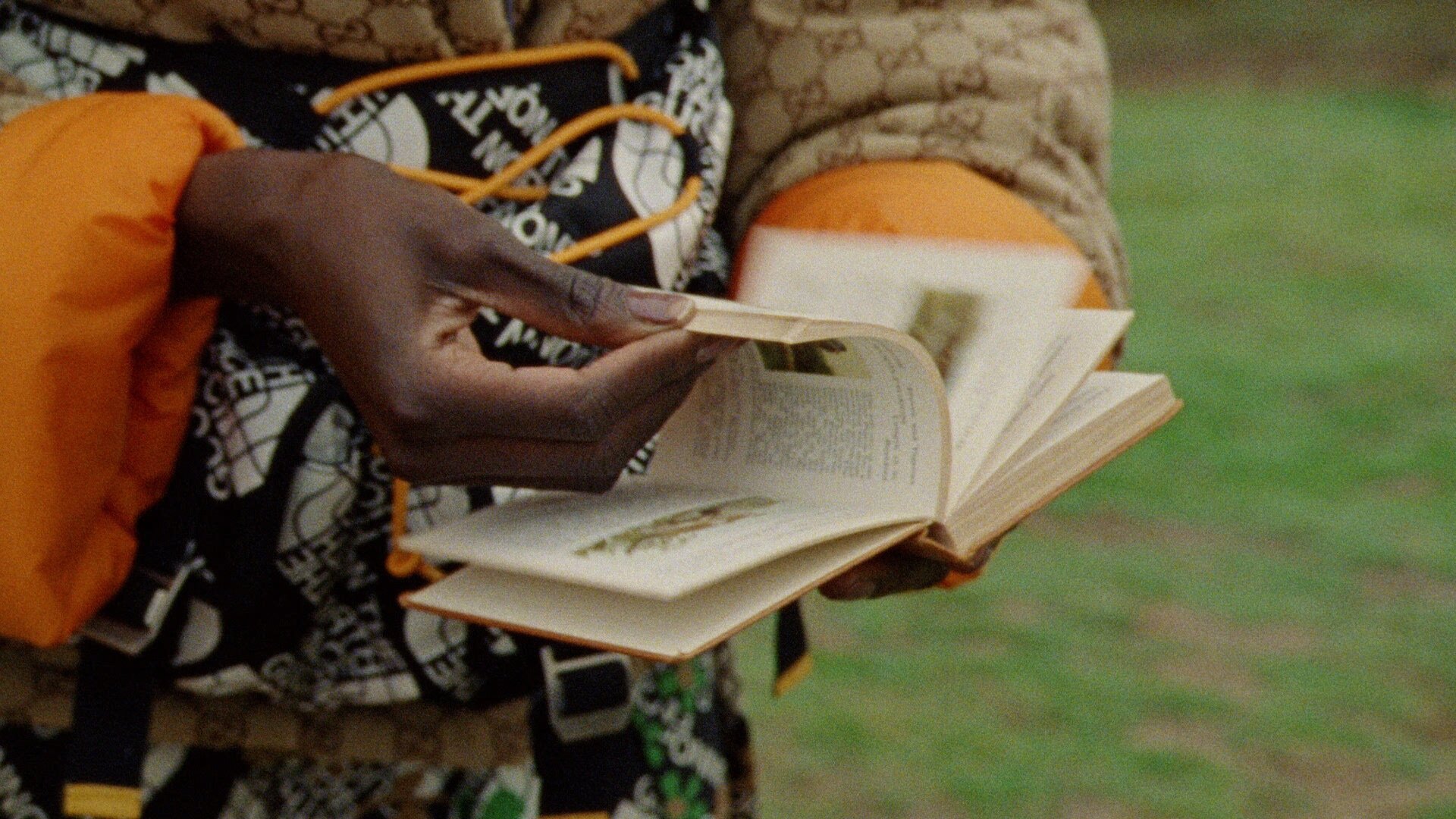

photographs by Domino Leaha

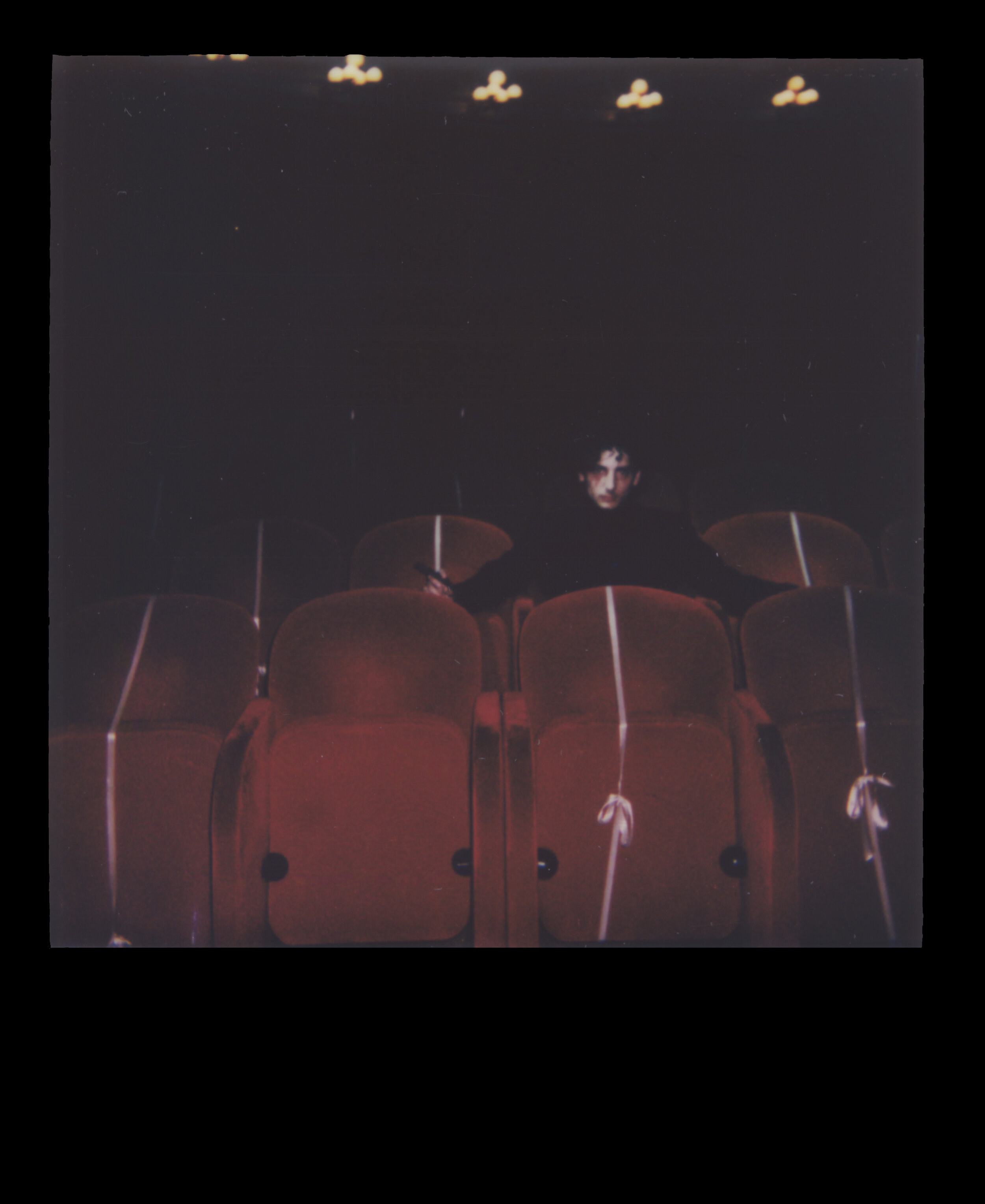

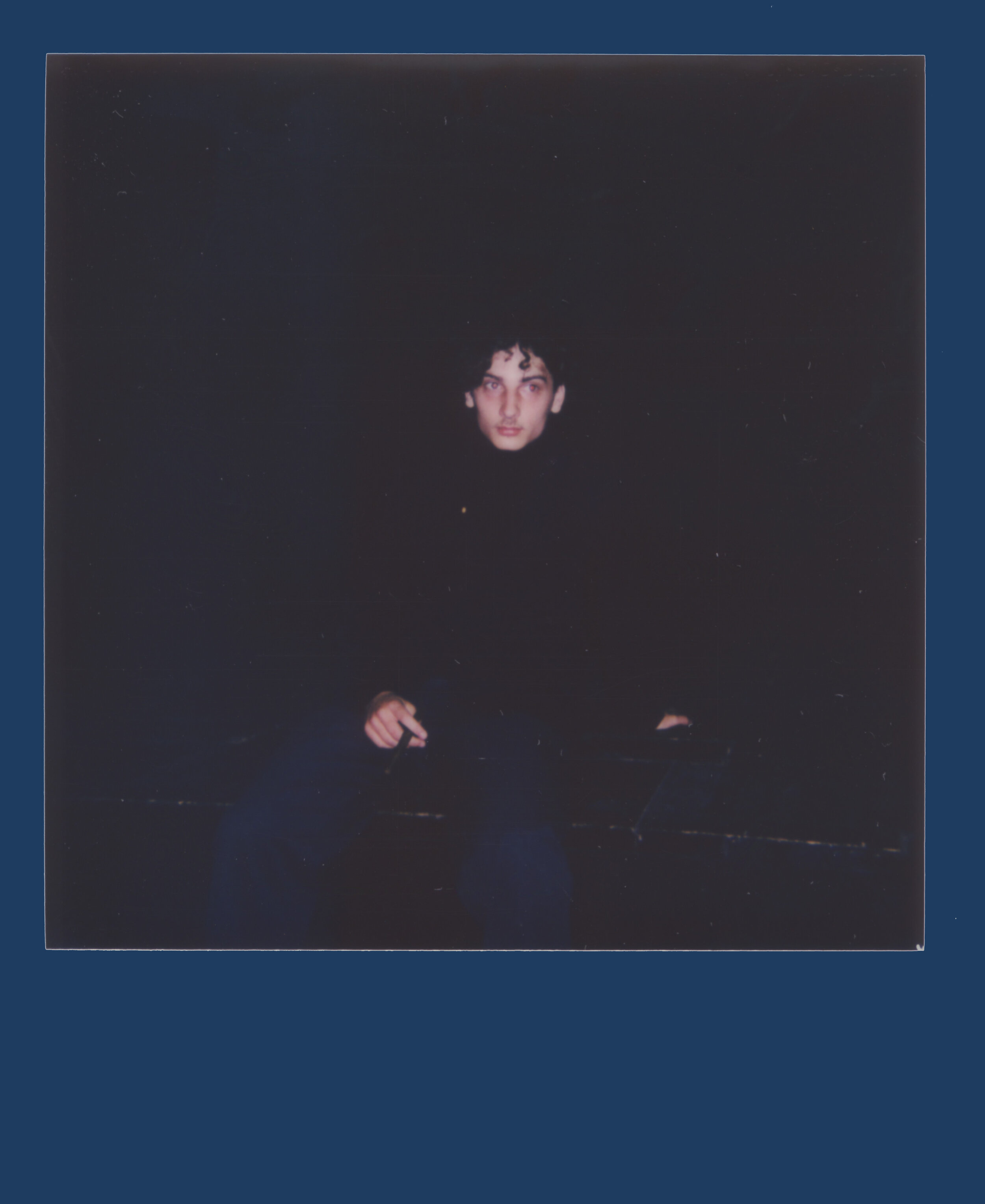

The London-based artist Jim Longden has released his debut short, To Erase a Cloud. Shot on 16mm film, the twenty-minute piece is “a sort of crash-course to the introductions of filmmaking.” To Erase a Cloud delves into the harsh realities of grief. The poet and actor Sonny Hall, a good friend of Longden, plays the painfully tormented, reckless and broken main protagonist, John Little.

The opening scene shows Little living a depressing existence in his dirty apartment; drinking dregs of empty beer cans and lighting half smoked fags as the early morning sun seeps in. We catch Little staring at his reflection in a cracked mirror; a symbol for his fractured state of mind and the result of his self-inflicted isolation spurred on from the loss of his mother.

We meander from the realities of Little’s daily existence, which includes taking a drunken cab to his mother’s grave, robbing a porno from the local off-licence, and surreal dream sequences that question the perception of Little’s reality. The poetic filmwork was made by Longden during the height of the covid pandemic. Although it may seem a desperate state of affairs, Longden manages to find beauty in the bleakness. As the saying goes; without darkness there is no light. To Erase a Cloud highlights humanity’s resilience to carry on.

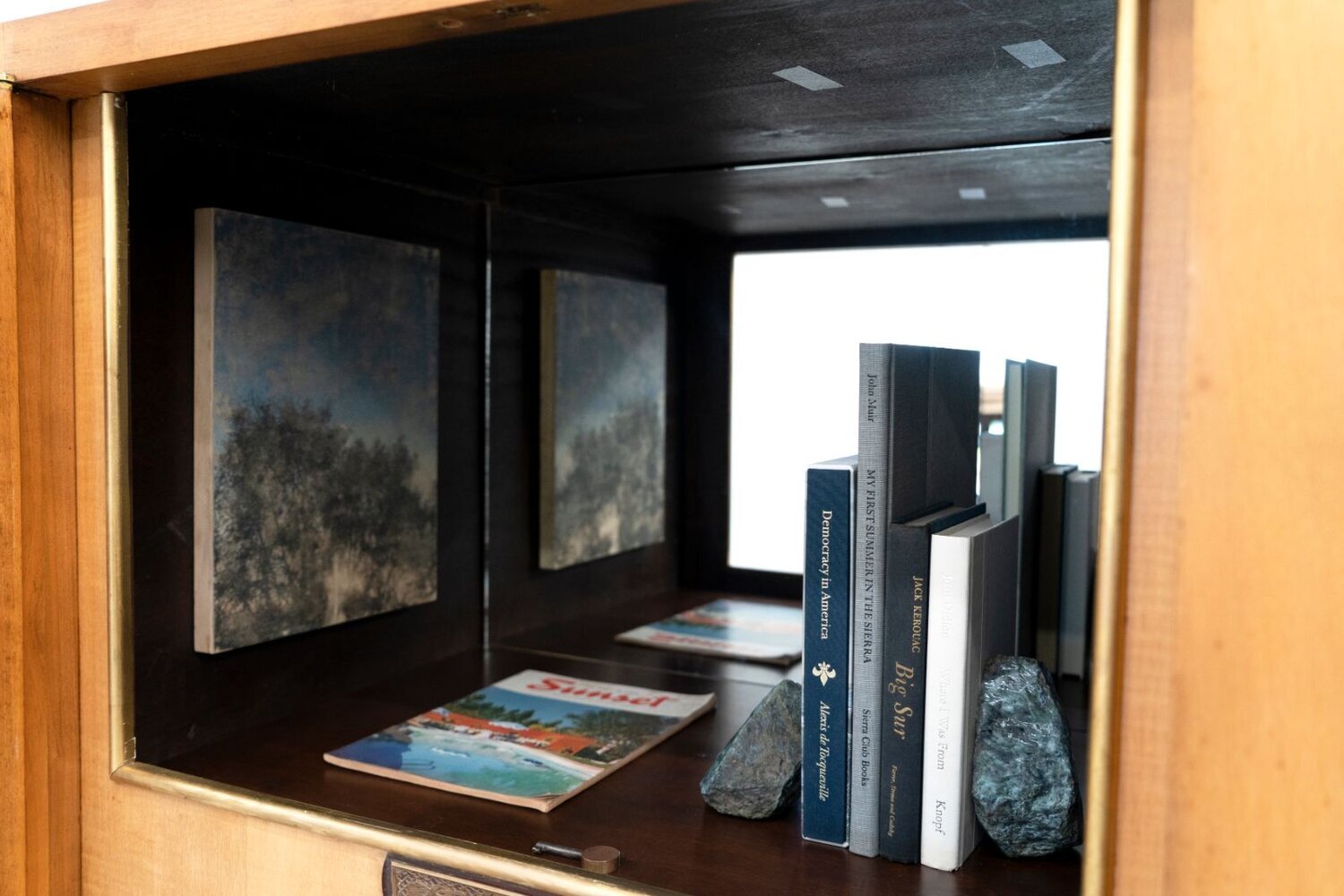

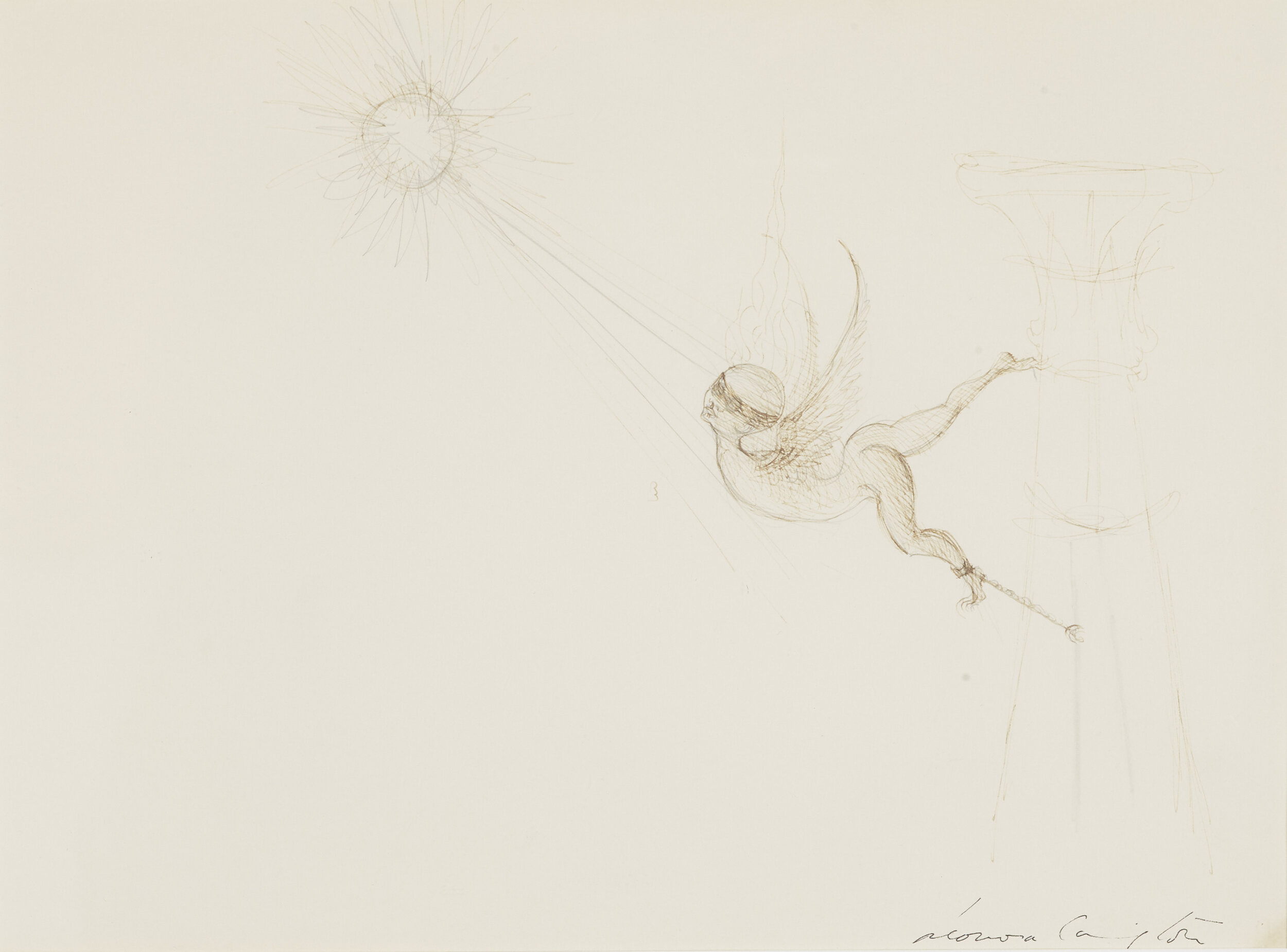

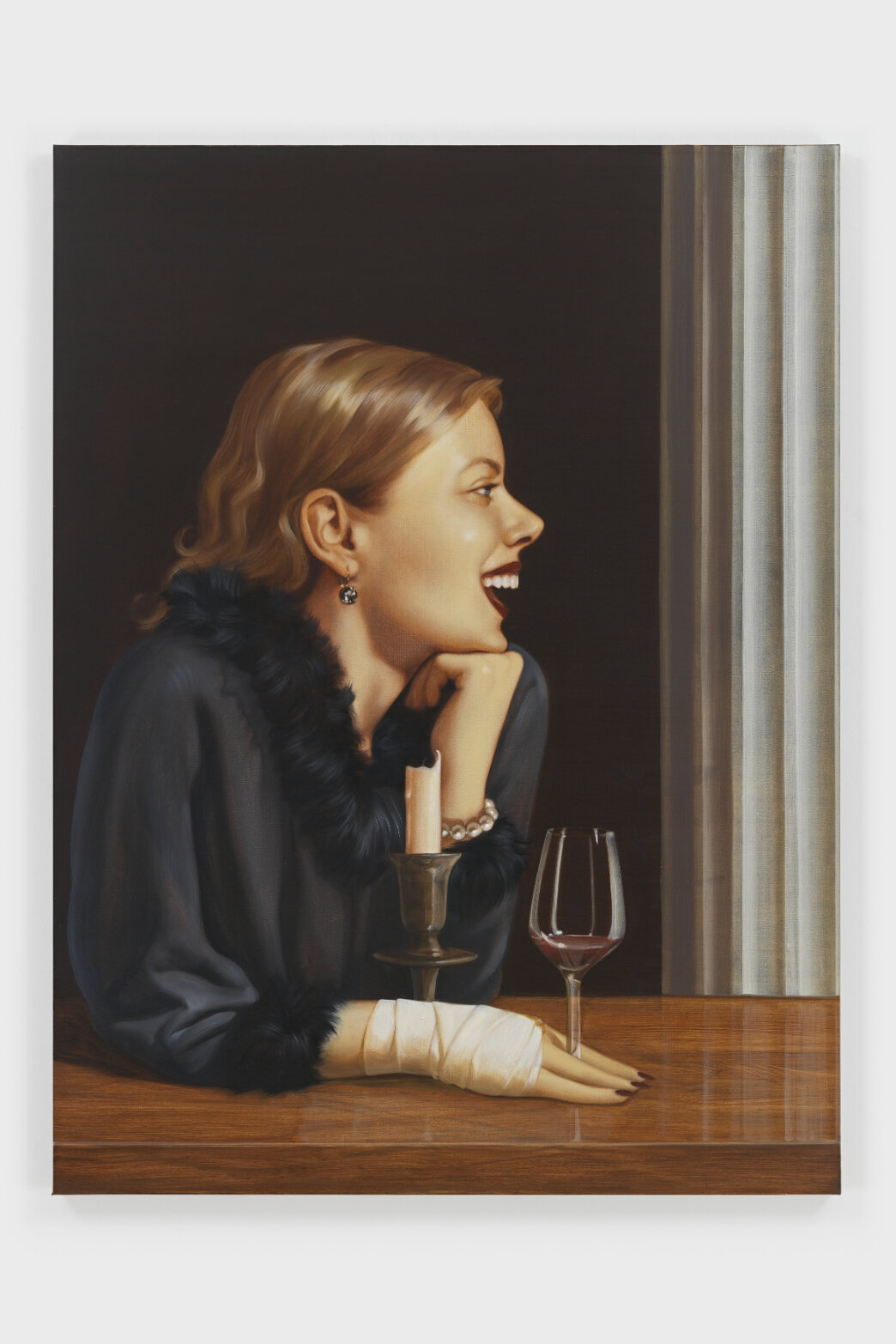

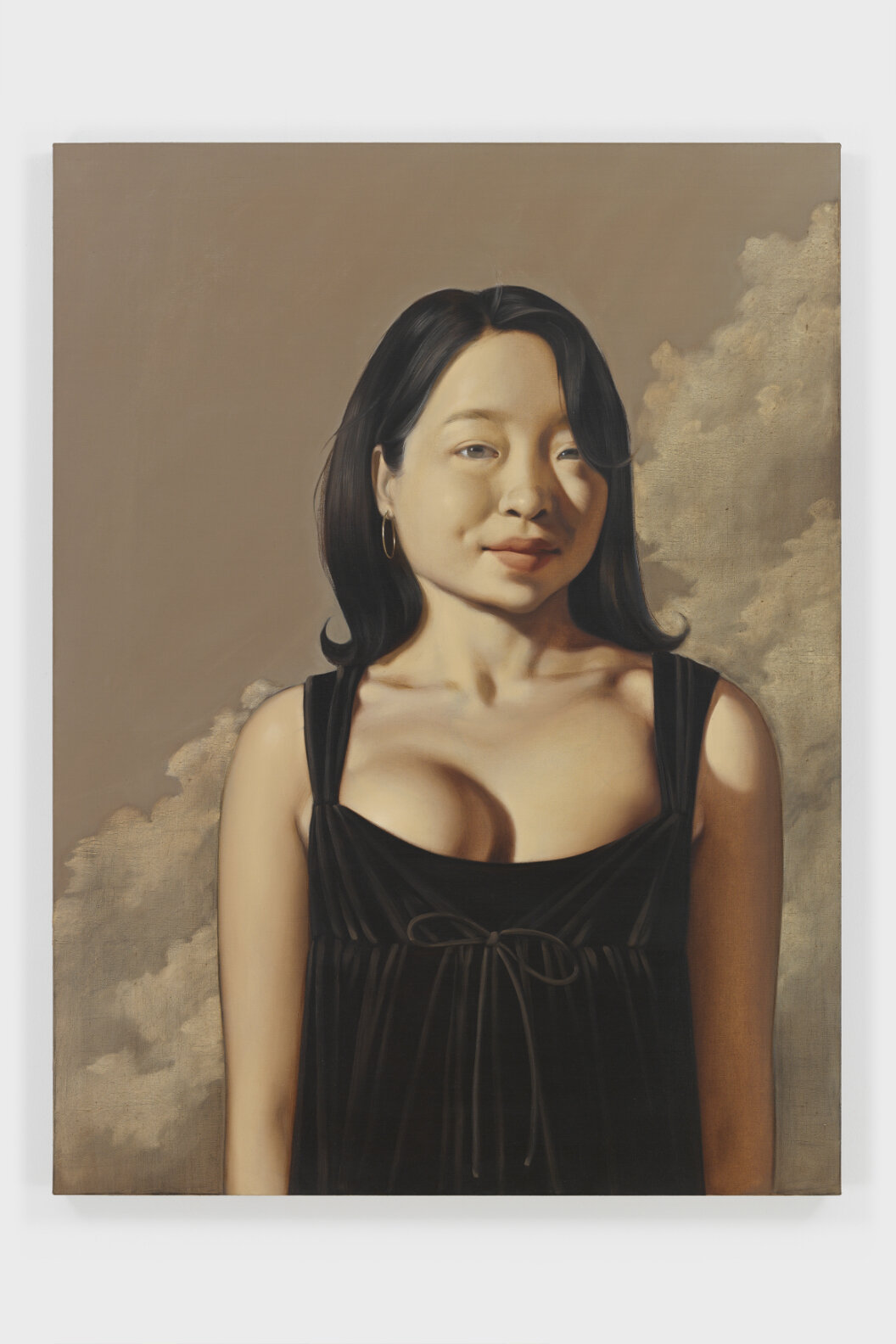

On a recent trip to Italy, Longden was shot by the Italian photographer, Domino Leaha for his interview with Autre. He is currently traveling around Europe, writing his next film.

LARA MONRO: Can you tell me about your most recent filmic work, To Erase a Cloud?

JIM LONGDEN: It’s a film about a young man being at that age when he should be passing the stage of the growing-but-stained teenager he was before, and to now be at the stage of finally entering adulthood. He is in this awkward middle, between his teenage angst, and his ongoing frustration and bitterness for the world and it’s ways. His mother not being alive, and him not being around her often during his younger teenage years, has left the character in this wayward mould of growing and developing. The character has a menacing side to him, but holds this poetic, and theatrical demeanor at the same time. We see the raw sides of his persona, but also hear from the mind which he holds.

We shot it in the year 2020; during the time of the pandemic. The film held this atmosphere of being set in an almost deserted ghost-town area, which resembled points of reality near to those times. I had written and directed the film when I was twenty, it was to me, a sort of crash-course to the introductions of filmmaking. The shooting was a three-day experience which I learned a lot from. I found the possible perception of the more experienced members of the team interesting, because of the fact that they were seeing people acting on screen for their first times, whilst also being directed by a director who had never directed before! I see the film almost as being the equivalent to a student film, a directorial debut. And, in that sense, I am pleased with the outcome.

MONRO: The main protagonist is the poet, Sonny Hall. How did you come to cast Hall in the film?

LONGDEN: Sonny has been a friend of mine for years. I knew he would be able to also help me with parts of the writing within it. And, he held a willingness to do things on camera, which I felt other’s may not have felt comfortable doing. Those stunts like him running into the car door of Benny Benson, and him punching the mirror after slapping himself as he faces it, were tough to see for certain people. When doing the rehearsals for that scene of him and Benny, he kept diving into the damn door in the run-throughs, we did not have a stunt supervisor present at any moment. He ended up limping for a few days after, but it was good to see this devotion from him.

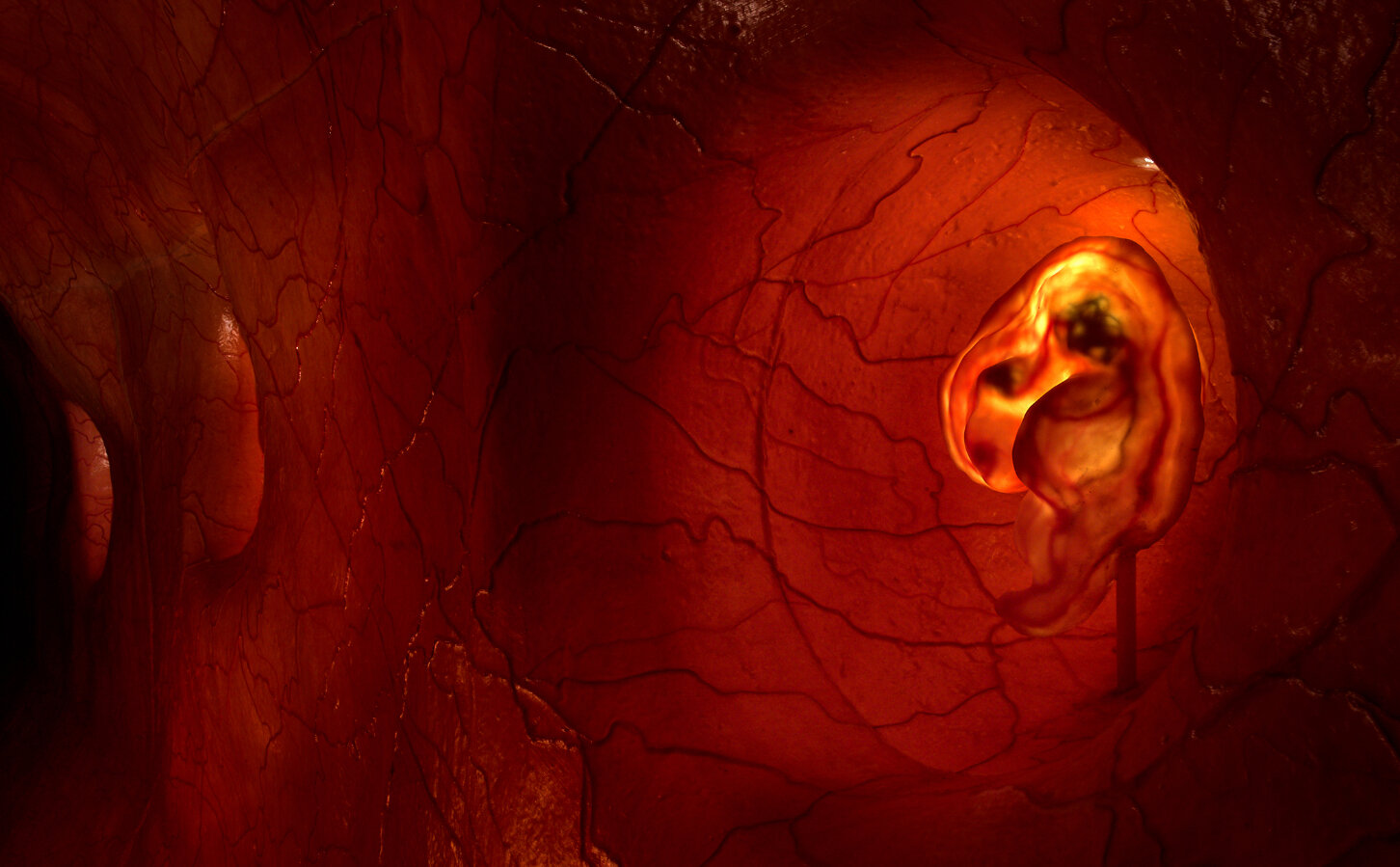

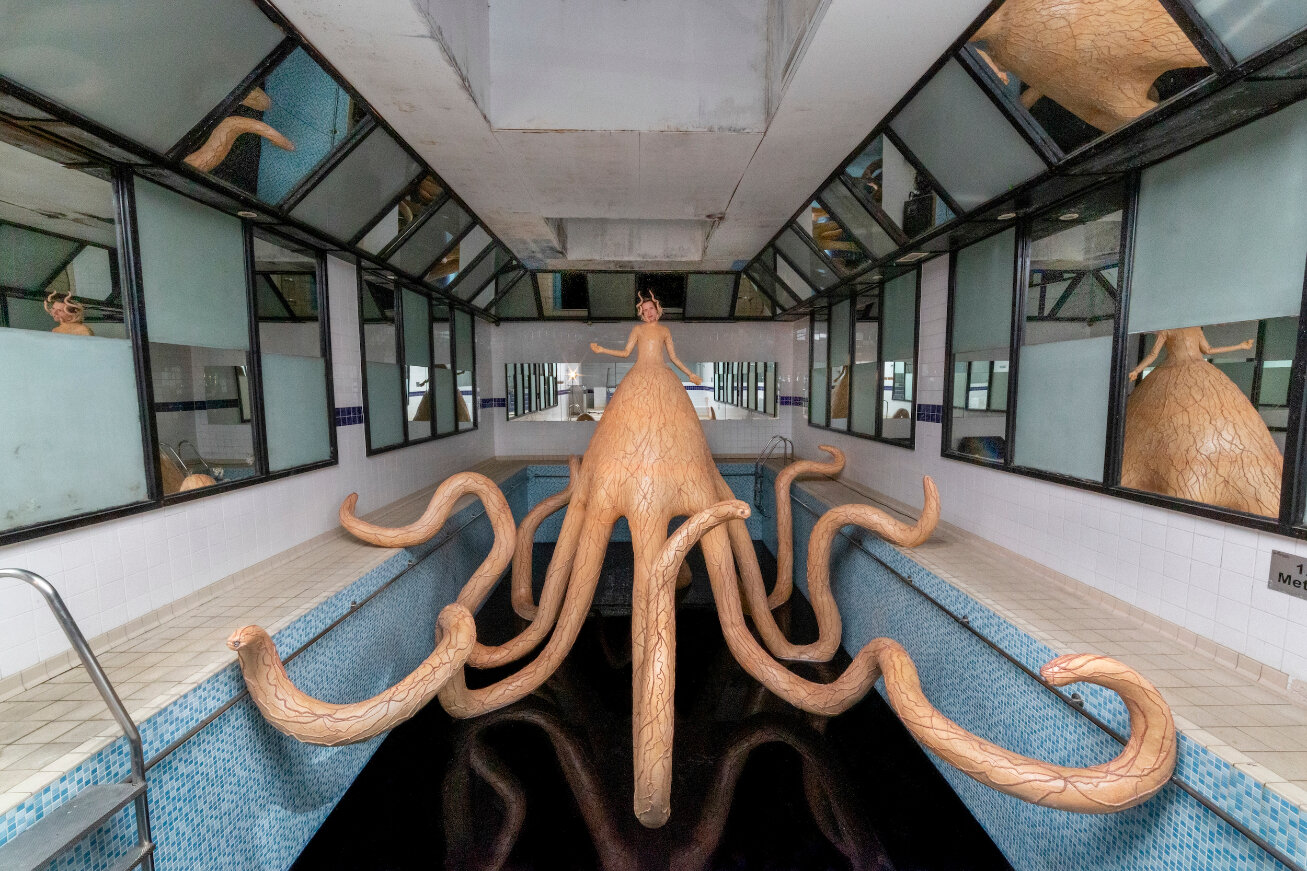

MONRO: To Erase a Cloud feels surreal in the moments when we find ourselves inside the tormented mind of the protagonist. Can you tell me more about these creative scenes and your treatment for these?

LONGDEN: Trying to make this film as good as it could be, while sticking to a very low budget was tricky. The access we had to certain locations was limited, so I had to almost treat it as if it were a theatrical story being told on the stage. I think the cinematography matched what sort of themes and styles we were aiming for. The music too, in my eyes added this blanket to the film. We used music made by Matt Elliott for the soundtrack. I had been a fan of his for years from when Sonny introduced me to his music. I also added in two guitar pieces I had created for the original score.

MONRO: Was the film mainly script-based or did you rely on improvisation?

LONGDEN: The story was mainly script-based. At a certain point, we had just enough time to fit in a newly thought up scene, which we rushed to film. And at another point, a scene we planned had to be cut due to it not working. Scenes like the Benny Benson one, had many improvised lines on his part, and certain movements as mentioned previously, could only be performed once, due to others being worried about the rightful code of health and safety. There are a lot of give and takes, sometimes they help, sometimes they don’t. The opening dance scene was an idea Sonny came up with, and on the day we were only able to film it in two takes.… Within a moment like that, the outline of the scene is there, but the rest is out of control, it is up to the subject to perform. We spent quite a while tweaking, adding, removing, changing things in the script, but at times, that could make one’s mind go around in circles. So, in that sense, I had to be careful and trust my instinct.

MONRO: Do you have a favourite scene, or are there any that stand out most to you for any particular reason?

LONGDEN: I liked the writing in the scene where we enter the mind of Johnny Little. I also enjoy watching the dream sequence he has.

MONRO: It seems you mainly work with film and photography. Have these always been your preferred mediums?

LONGDEN: Yes, they have. I had swerved within different lanes after leaving school, to survive and to keep myself busy. But, when I was younger, I wanted to become a professional football player. And when that dream faded, I was saved by the thrill of wanting to take photos and make films.

MONRO: Are there other mediums you would like to introduce into your creative practice?

LONGDEN: Maybe joining a Gypsy guitar band or something?

MONRO: Your website also features clothing. When did you first venture into fashion, and can you tell me what CAPO stands for?

LONGDEN: The clothing is merely merchandise, which is how I am able to keep my stomach full.

MONRO: You left school at sixteen to follow your creative pursuits. Did you face difficulties infiltrating the creative world as a self-taught artist/filmmaker?

LONGDEN: I wouldn’t say difficulties, I was more just upset at the fact that I didn’t know who to trust. I didn’t know what was real or not. I didn’t want to play snakes and ladders. I was at a blossoming, but vulnerable age, and didn’t want to have the blood sucked from me. I wanted to stay true to what I believed in, but at the same time, I needed to be able to move forward. It was an experience, that’s for sure.

MONRO: Are you working on anything else at the moment?

LONGDEN: Over the past few years, I have been taking photographs for a book I want to create. It holds the working title, Where You Are When You Don’t Know Where You Are?. I really look forward to being at that blissful moment when I think the book is ready and complete.

I also started writing passages, for what can maybe one day become a book. I am not certain of this happening any time soon though, I think I need more time to develop my writing before releasing it. But, it’s in motion, currently holding the working title of, Memoirs of a Balloon.