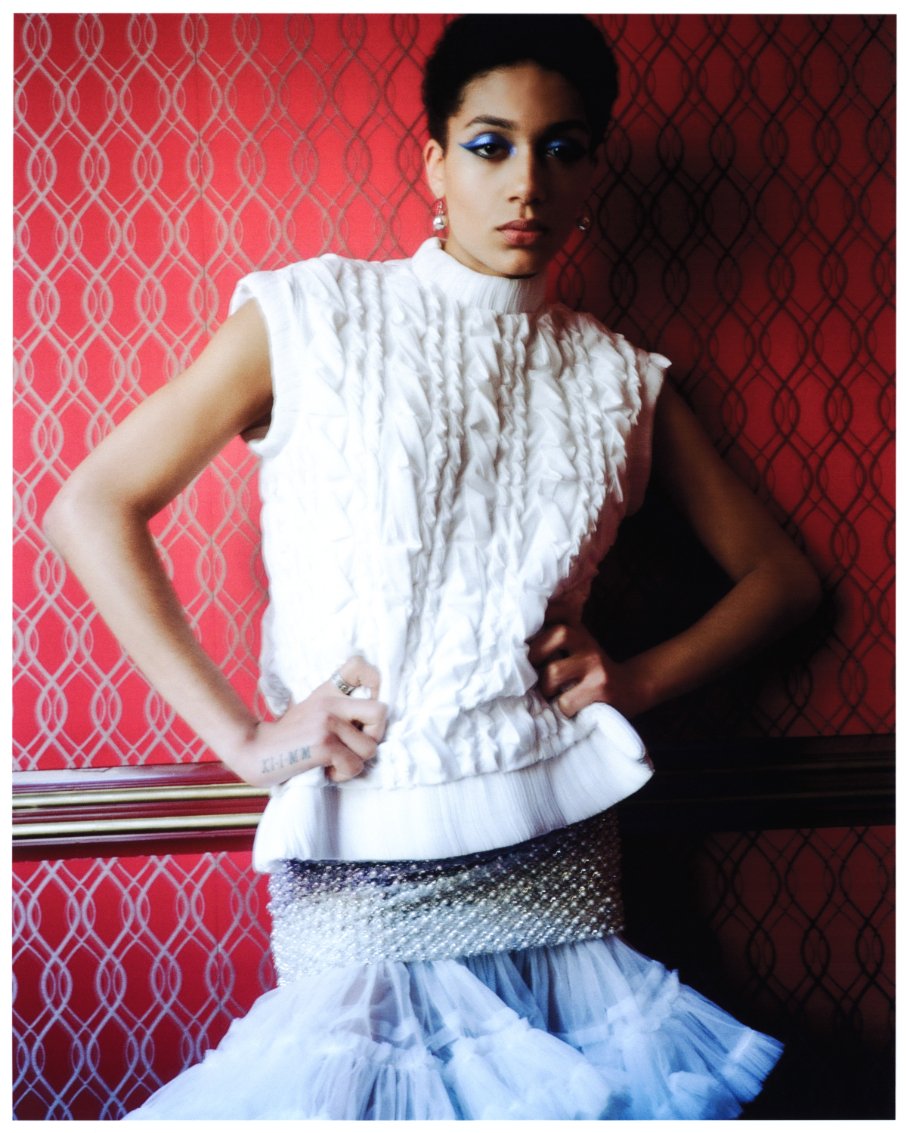

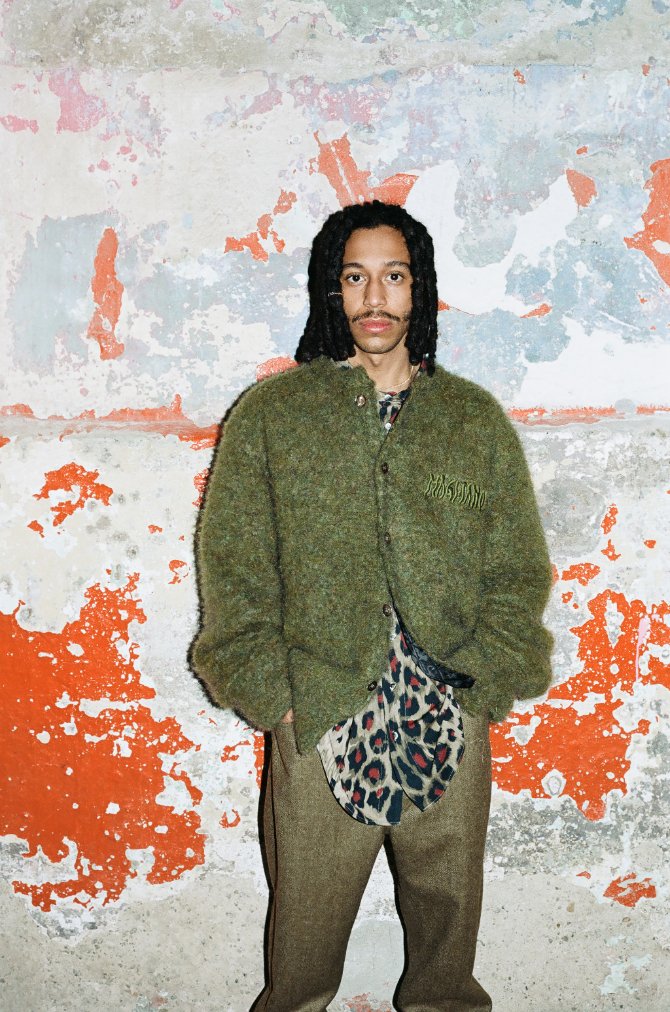

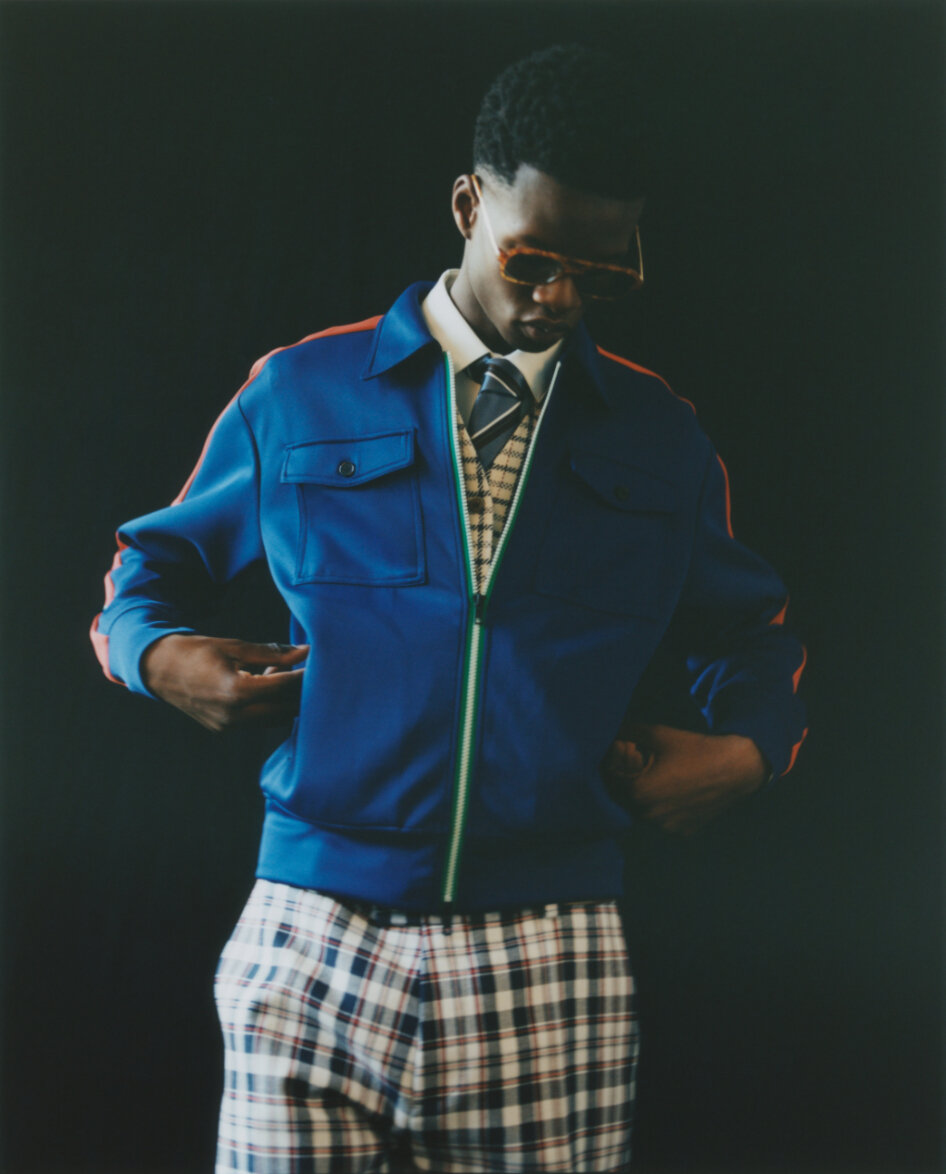

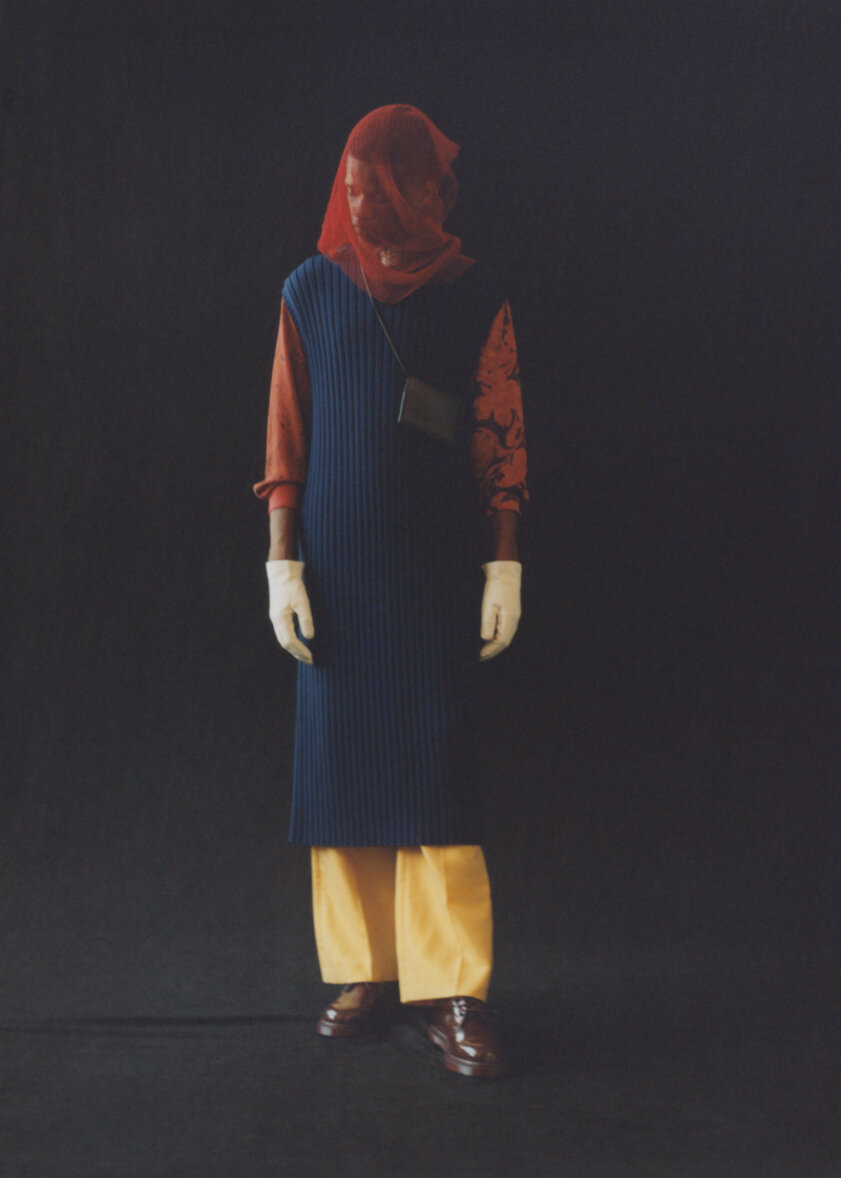

photography by James Emmerman

styled by Sintra Martins

makeup by Mical

modeled by Memphis Murphy

interview by Camille Pailler

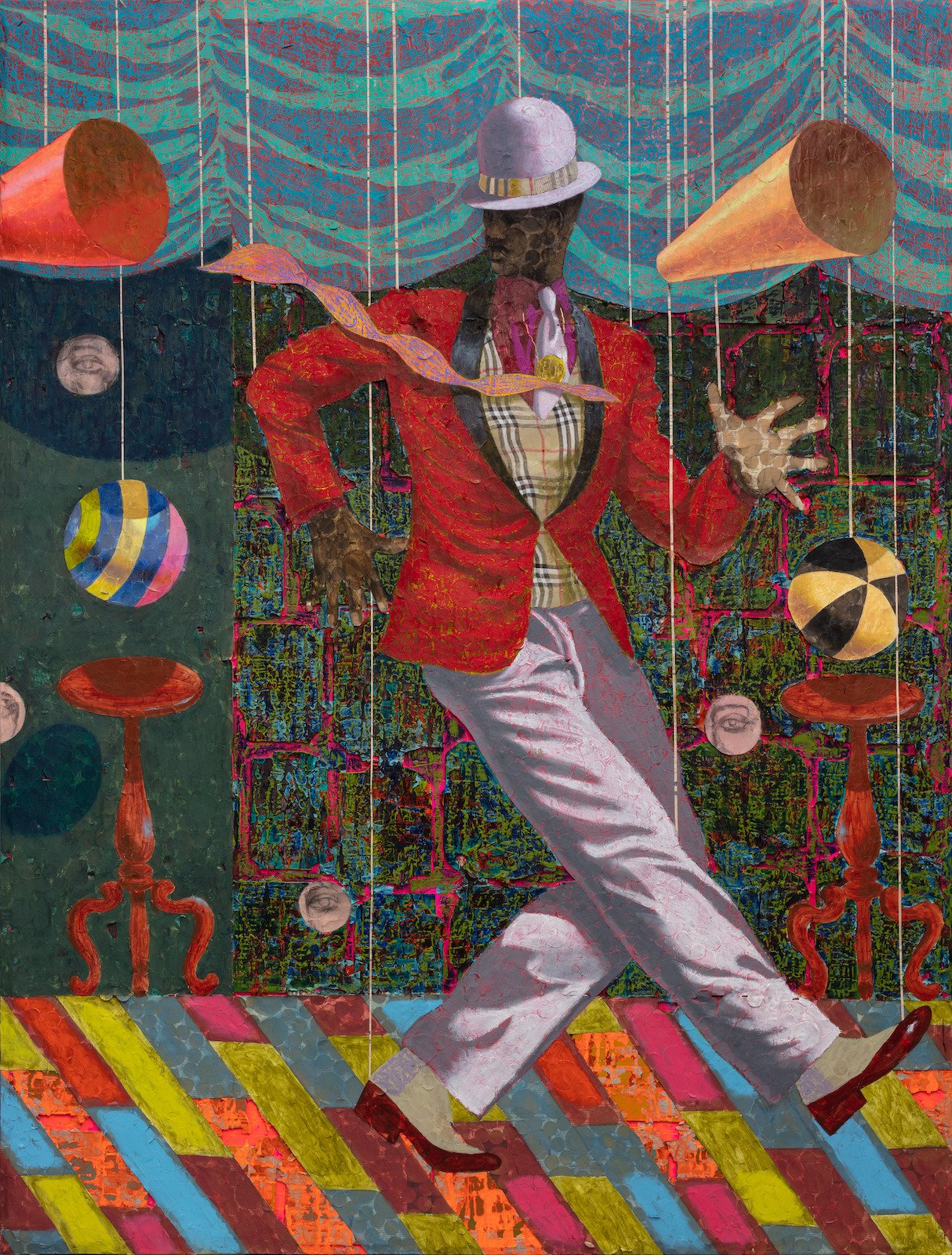

Sintra Martins may be from Los Angeles, but her designs are quintessentially New York and they are taking the city by storm. The recent Parsons graduate interned for Thom Browne and Wiederhoeft before launching Saint Sintra in 2020, presenting her first collection at NYFW in 2021, and her sophomore FW22 collection was just presented at NYFW earlier this year. In the last two years, her sculptural designs have walked the line between costume and ready-to-wear with S-curved horsehair filaments, sheer maxi skirts, colored feathers, English shetland tweeds, sparkles and bows, and so much more. Not only has she established herself as a master of disparate materials who takes inspiration from far and wide, but her designs have become instant favorites to everyone from Olivia Rodrigo, to Sydney Sweeney, Willow, Cali Uchis, and Kim Petras. We asked Martins to style model Memphis Murphy for a special editorial and sat down to ask the emerging designer a few questions about her process.

CAMILLE PAILLER: Can you talk about the way that you incorporate absurdism in your design?

SINTRA MARTINS: Absurdism is really at the core of the brand’s identity. It starts on the boards, collaging imagery until I recognize traces of the dissonance that arises when I lose track of what I’m trying to say. I think the best work exists just beyond the edge of familiarity, like a cartoon cliffhanger.

PAILLER: You went to Florence and fell in love with the city. How did this experience influence your latest collection?

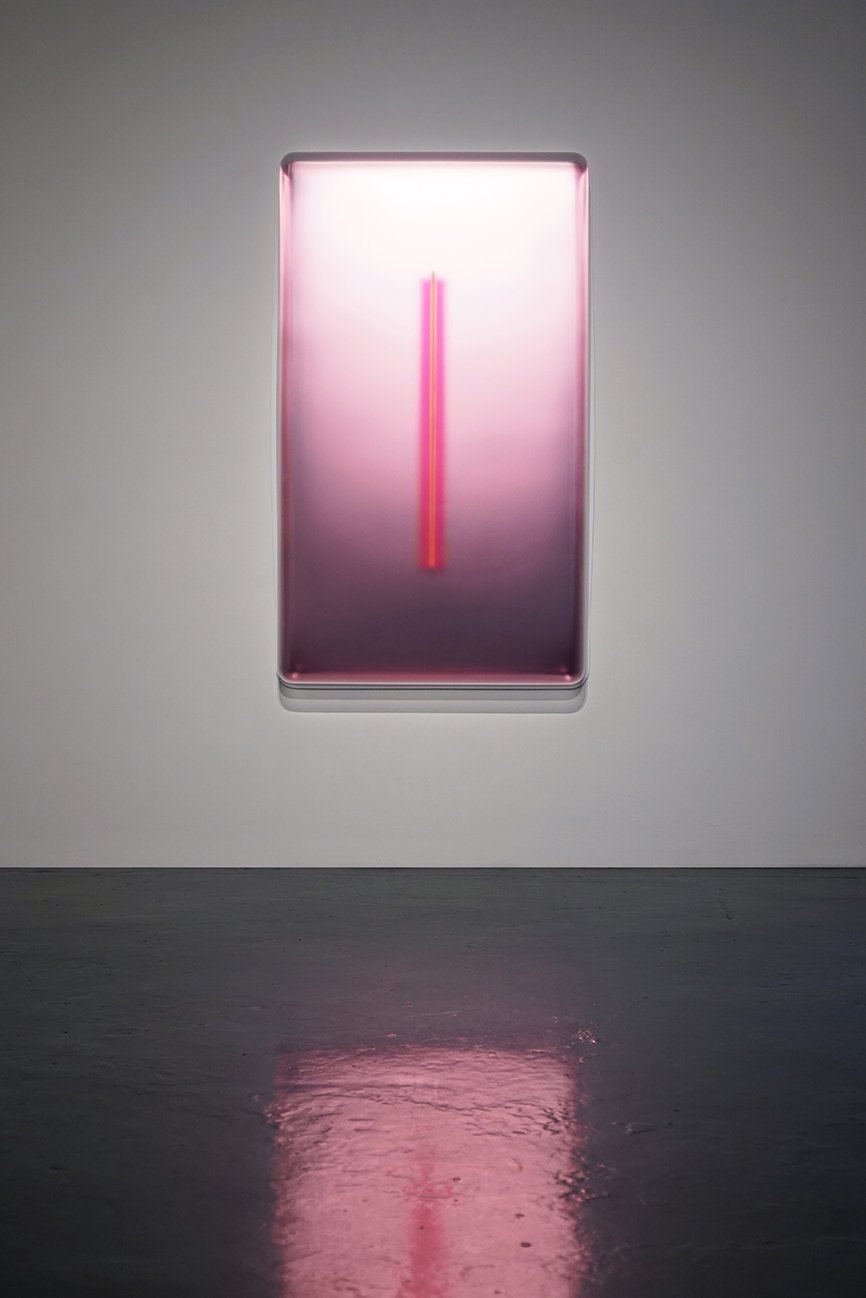

MARTINS: Florence is heaven on Earth, a Disneyland for Renaissance art history nerds, and home to some of the most incredible artisans in the world.

Our FW22 collection was more directly inspired by armor, I’m really interested in the engineering of articulation, and how a material so rigid and inflexible as metal can take on the human form in all its complexities. It was also fascinating to see the legacy of the Medici family in person. I’m really interested in the idea of feudalism as it mirrors to our current political landscape, and how beautiful it can look despite all its humanitarian shortcomings.

So often I ask myself, what is the purpose and meaning of fashion? I think Europe has a rich cultural and anthropological legacy of fashion, which is evident in their culture in a way that I really admire and value. Spending a few weeks in Paris and then Florence was a refreshing reminder of the importance of fashion in a cultural sense, not just as a niche hobby, or content fodder as it can sometimes feel here in New York.

PAILLER: You worked in the Parsons archives. I’m curious if you have a favorite period in fashion history?

MARTINS: Favorite questions are so hard. There’s something nostalgic about anything that was ever fashionable. I do love to see exposed stitches on an antique garment, it’s a beautiful reminder of the labor and love that went into making it. If I had to choose I’d say the transitional period between what’s considered Edwardian and Deco, though I’m not sure it has a name.

PAILLER: You're fresh out of school and have hit the ground running. Who influenced you most as a designer while you were in school?

MARTINS: I take inspiration from some cliché amalgamation of McQueen, Galliano, Marc Jacobs, Westwood, and more contemporary designers that have managed to break through the post-graduate slump.

PAILLER: The beaded dress Memphy is wearing has a very precise cut and ornamentation. Can you tell me more about the manufacturing process and the reference for this dress?

MARTINS: The Memphy dress was inspired by a Cardin carwash dress I saw in a vintage shop, and I thought how cool would this be if it were sparkly? Ultimately it looked horrible, and I had to scramble to fix it, so I decided to sew the strips into tubes, and my assistant and I played around with it until it didn’t look so horrible. Ultimately I think it came out much better than I’d imagined, but totally different. Like I mentioned earlier, innovation is just outside the comfort zone.

PAILLER: Can you tell us anything about what to expect from the upcoming collection?

SINTRA: No! Top secret.