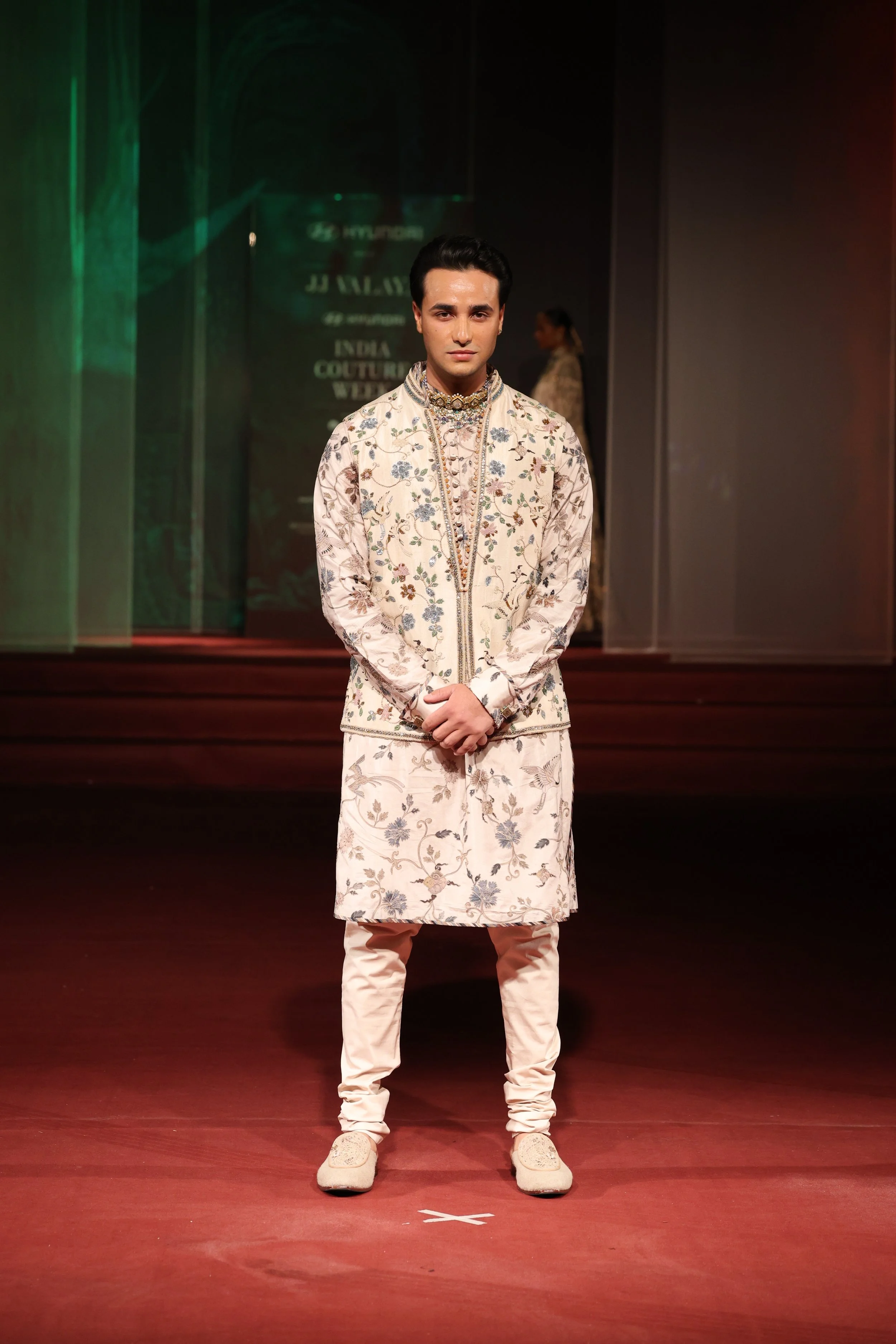

No one stages drama quite like JJ Valaya, and East—his closing show and a celebration of 33 years in fashion—was an imperial epic. A curation and compilation of Ottoman silks, Rajput extravagance, and East Asian tapestries, the collection was detailed and imaginative. Catalogued a collection where there was something for all, embroidered jackets, obi-style belts, brocaded cloaks, and voluminous skirts, as if they were brought to life.

Rasha Thadani and Ibrahim Ali Khan closed the show with old-world poise and new-world flair. It was a fitting finale—part history lesson, part fantasy film.

Aisha Rao — Wild at Heart

Making her ICW debut, Aisha Rao was the season’s freshest dream. Her collection Wild at Heart bloomed with lotus petals, banana leaves, and rose-gold mosaics—each appliqué whispering a kind of untamed tenderness. She layered nature into couture like a fable.

Sara Ali Khan was stunning in a beautiful Banarasi lehenga. Rao's world feels like a place where rebellion is subtle and fantasy is intricately woven with thoughtful details. The entire show was truly unforgettable.

Ritu Kumar – Threads of Time: Reimagined

A quiet storm came in the form of Ritu Kumar, one of the original matriarchs of Indian fashion. In Threads of Time: Reimagined, Kumar revisited and revitalized her archives, reworking iconic prints, paisleys, and kalidars for a new generation. It felt like a love letter to Indian textiles, with the wisdom of decades and the freshness of reinvention.

This wasn’t nostalgia—it was memory made malleable.

What We Saw, What We’ll Remember

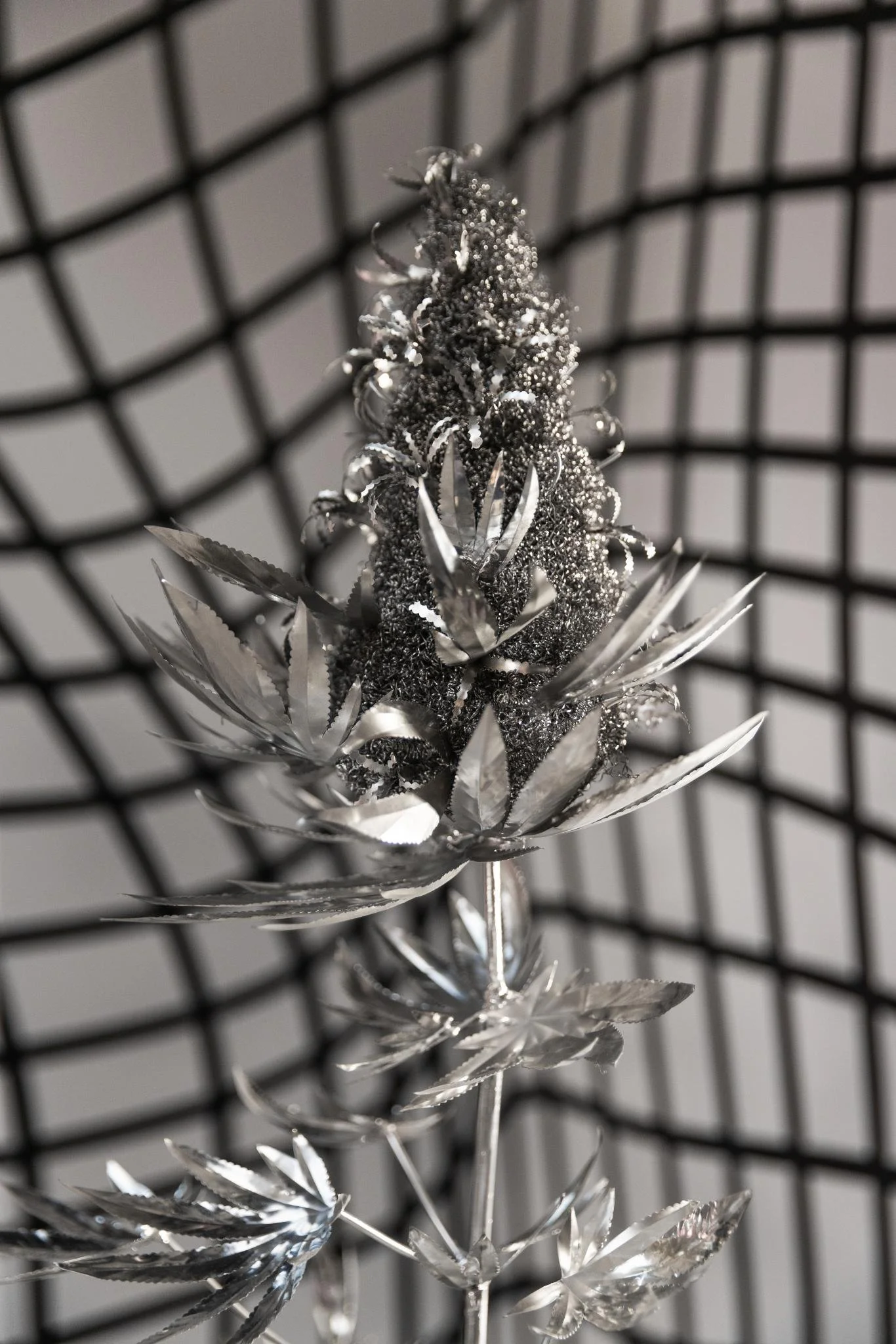

This year, ICW saw a return to tactility. Couture was about touch—embroideries you could feel with your eyes, textures that moved like memories. There was structure, but also surrender. Motifs of roots, DNA, nature, and spirituality ran across collections like leitmotifs in a symphony.

We saw metallics meet brocade, corsetry meet kalidars, and flowers sprout from pleats. And above all, we witnessed a reclamation of Indian identity in high fashion—not as tokenism, but as a language only we know how to speak.

India’s couture scene is now more intimate and more international than ever before. With young voices like Aisha Rao stepping in with fresh fantasy and veterans like Rahul Mishra and Amit Aggarwal pushing boundaries between concept and craft, couture is evolving. Indian fashion today isn’t just bridal lehengas, it’s chronicles of the land, reflected in silhouettes and fabrics, expressed by the artists, with imagination for the bold futures.

The designers were encouraged to reflect, dream, and truly connect with their vision.