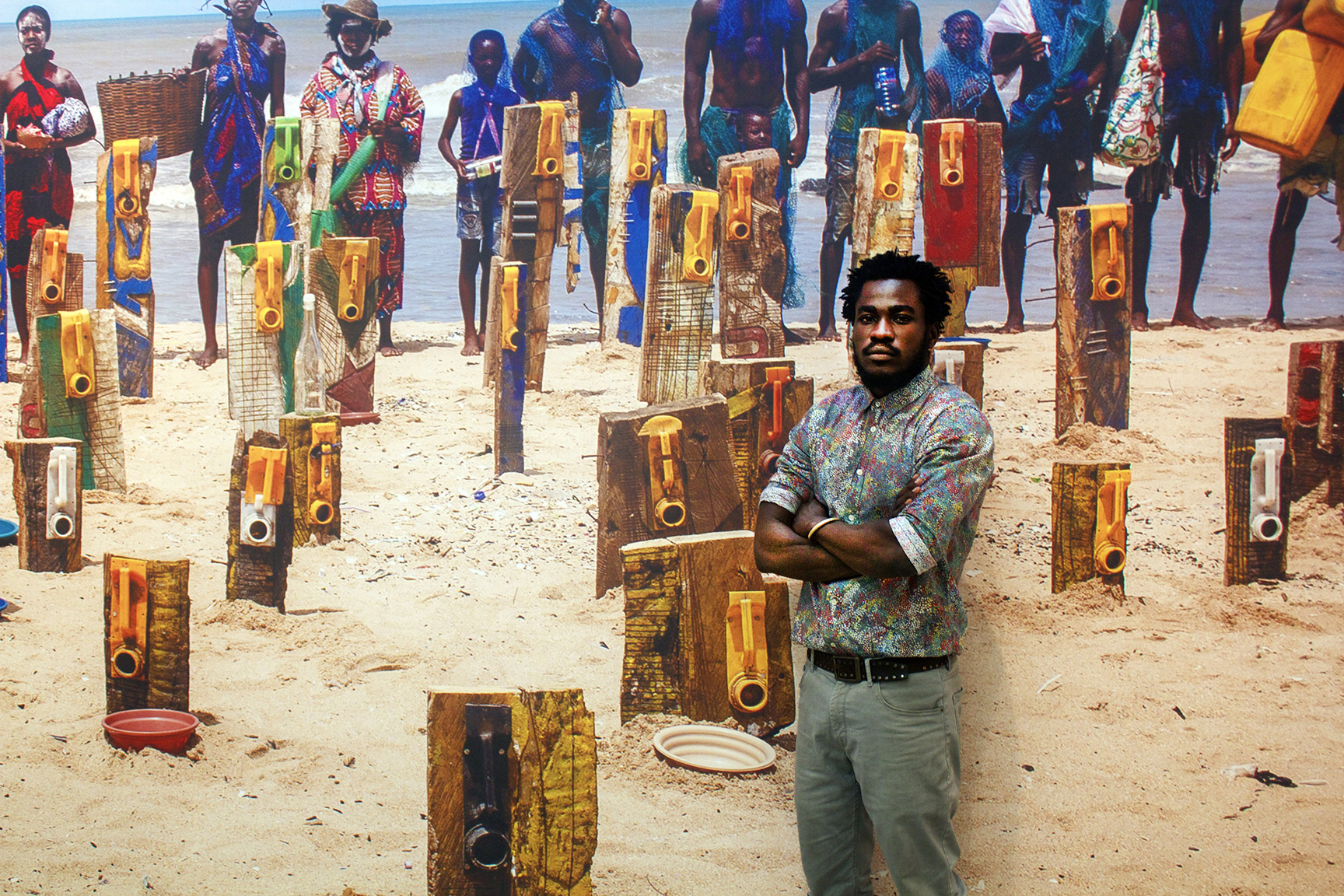

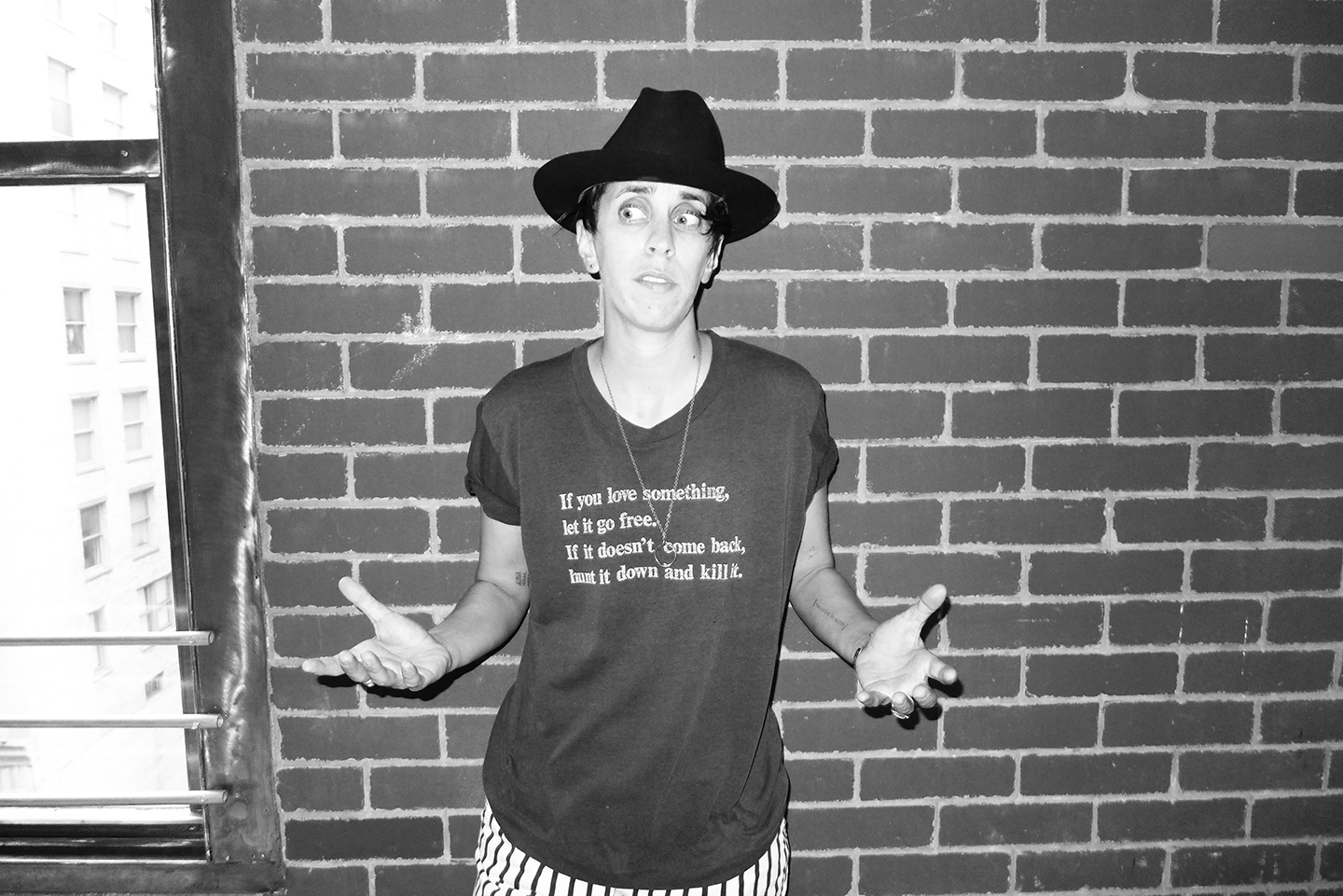

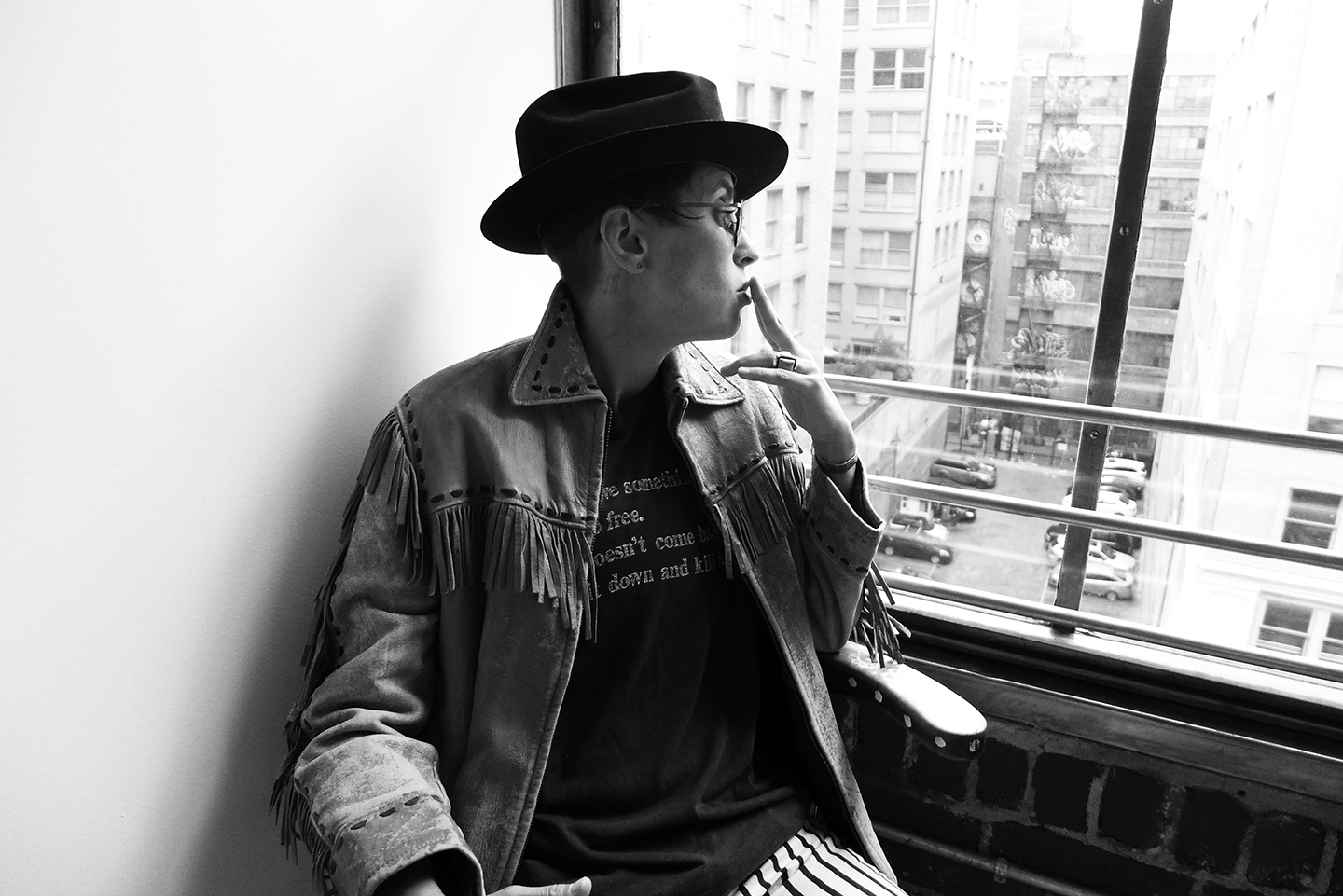

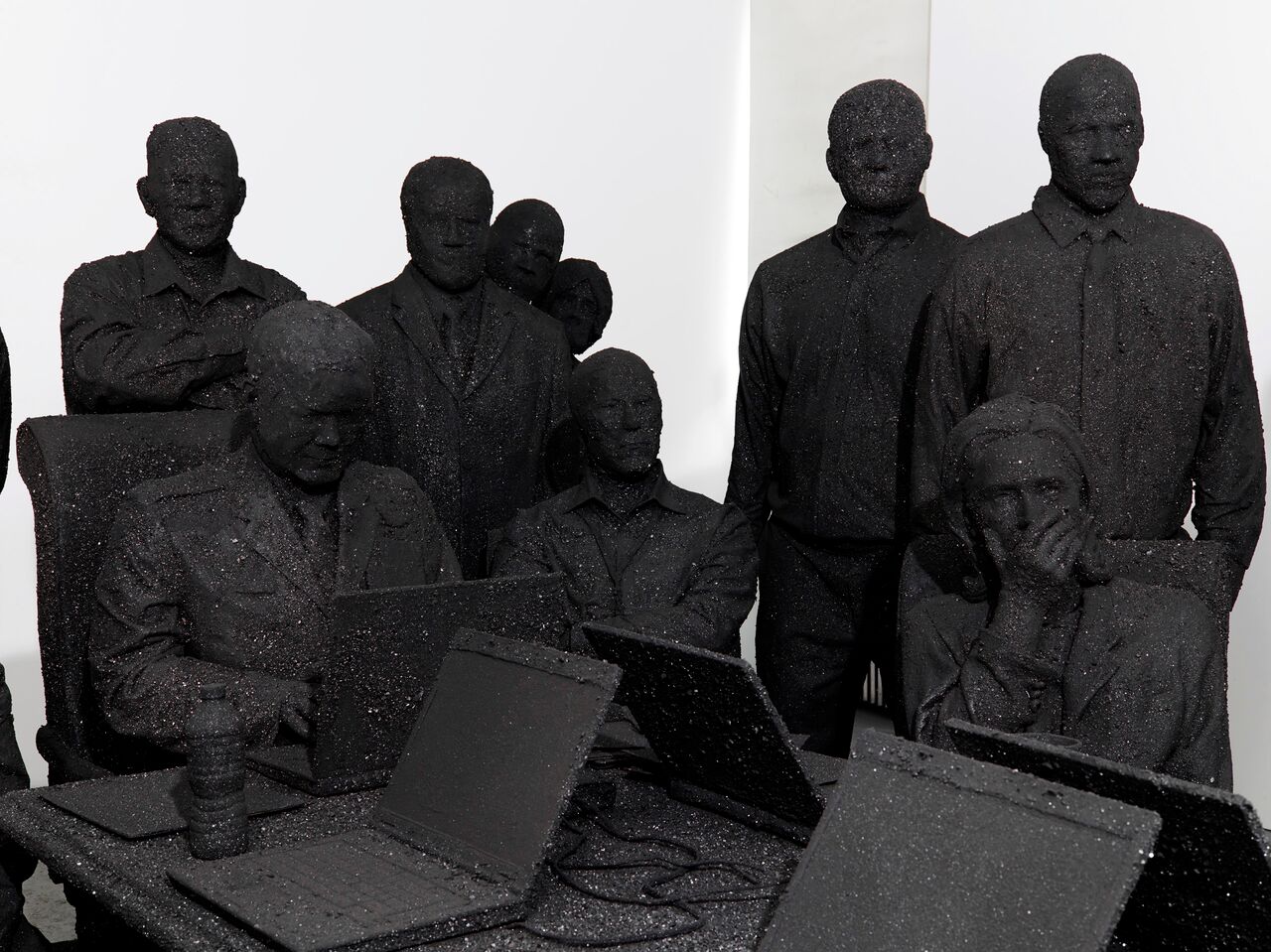

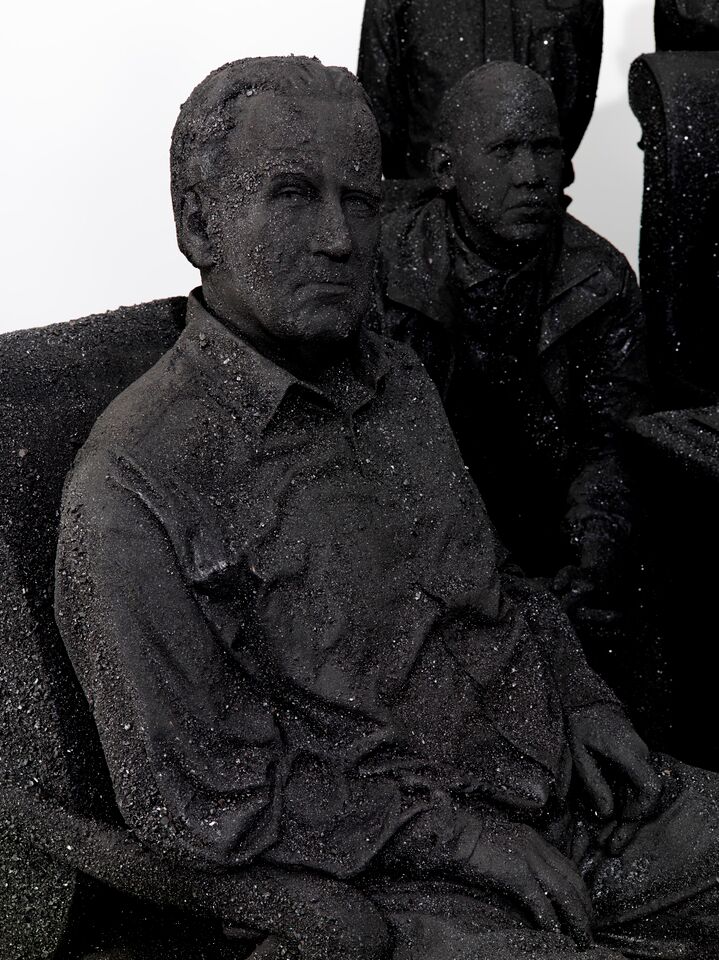

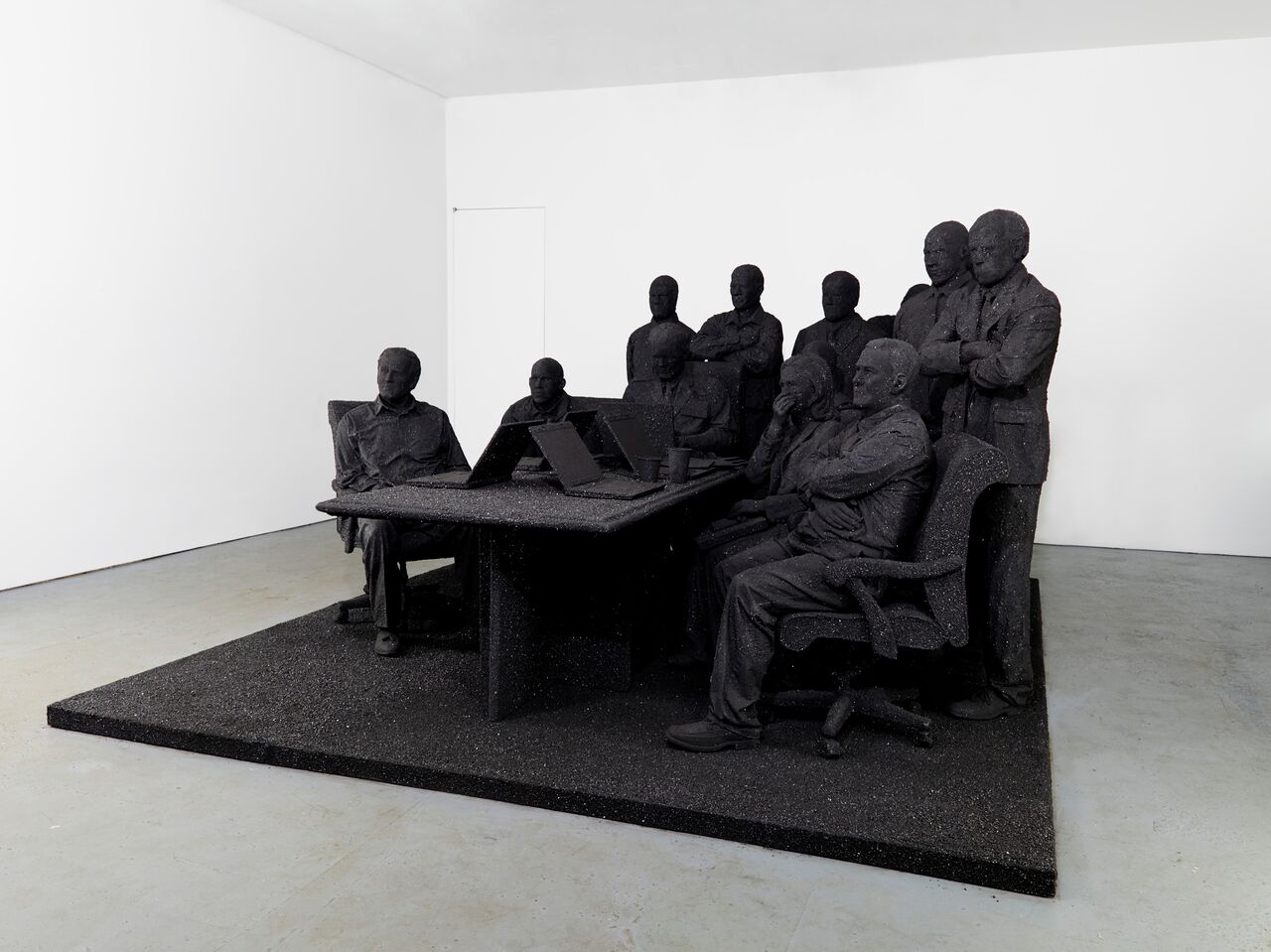

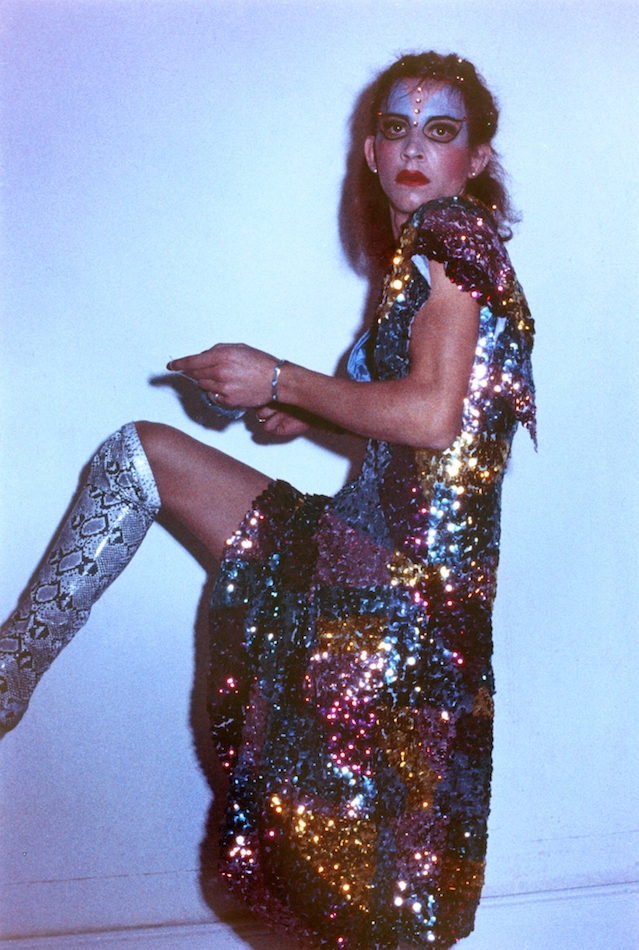

Artist Annina Roescheisen is making her name known in the art world. Right now, you can see her formative series What Are You Fishing For? at the Venice Biennale, in the context of the European Pavilion. Starting today, the German-born artist who received her degree in art, philosophy and folklore from the elite Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich in 2008, will see her first solo gallery show in New York. Her series What Are You Fishing For? is emblematic of her work: rife with symbolism and metaphor, and dripping, literally, in pictorial beauty. In the following interview, Annina talks about the use of metaphor in her work, her experience getting to know New York and the meaning behind her self-designed tattoos.

Ariana Pauley: There are a lot of metaphors that you use in your work. Do you come up with the metaphor beforehand, or is it a fluid process?

Annina Roescheisen: It’s more of a fluid process. The whole story-writing is a process. It starts with a keyword or a phrase that I write down; I always have these little books with me. There are a lot of things going back and forth. Often, I have five things spinning around in my head at once. At a certain point, there is one story that ends up pushing forward. It can come from anywhere. So, the symbolism comes more naturally. It’s something I like to play with, but I don’t construct the work around the symbolism. It’s just a manner of expressing myself.

AP: For the film that was in the biennial, what would you say were the most important metaphors?

AR: In this one, I think it’s about life, death, and Renaissance. There are many others, but I would say those are the main three.

AP: How was your experience at the biennial? How did it all come about?

AR: It came through a gallery in Berlin—Circle Culture Gallery. The gallery owner really likes my work, but I don’t fit into his program (he’s more into abstract art, graffiti, etc.). He’s really very supportive. When he saw the film, he was applying for the Venice Biennale with another artist, and he proposed that I apply my film with him. I’m a young artist; I never thought they would say yes. But I had the answer in two days. I still don’t understand it sometimes. It’s so unreal that I just do it. I think it’s good, sometimes, to not understand what you’re going to do. It’s best to just do it.

It’s a tiny, tiny room. I don’t have the biggest room. But I am so happy to participate and to have the whole atmosphere.

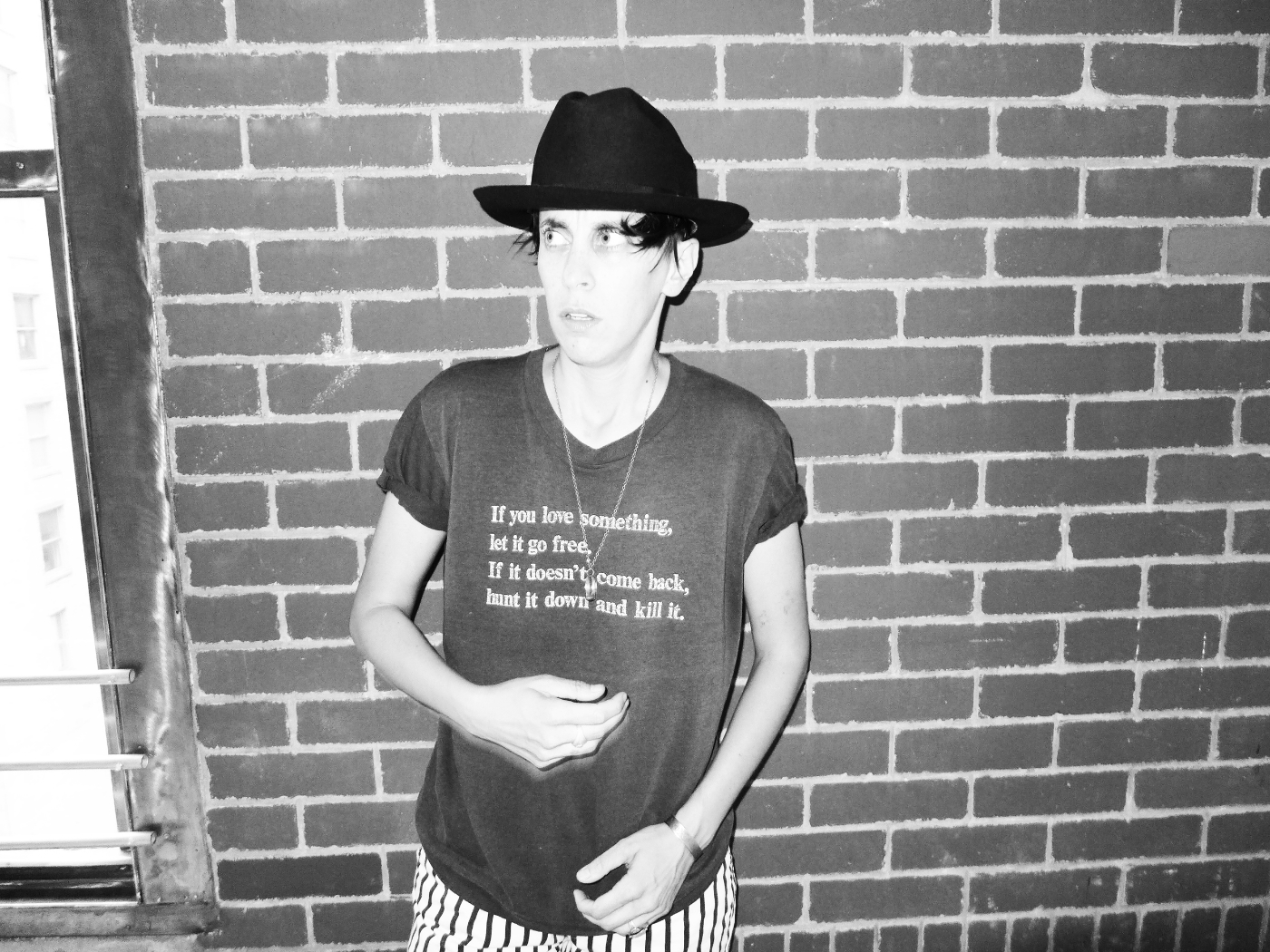

AP: You just moved to New York. Are you nervous that the culture is going to affect your art? Do you think your time in Paris affected your art in a certain way?

AR: I think it always affects your art, where you live. In general, no matter where you live, it’s just about growing up. Definitely, my art is going to be affected, in a way. But it’s also growing more as a woman and growing up in general. Paris was good to grow up, as an artist. I feel more apt to face a bigger audience.

AP: Was there a specific reason why you decided to come to New York?

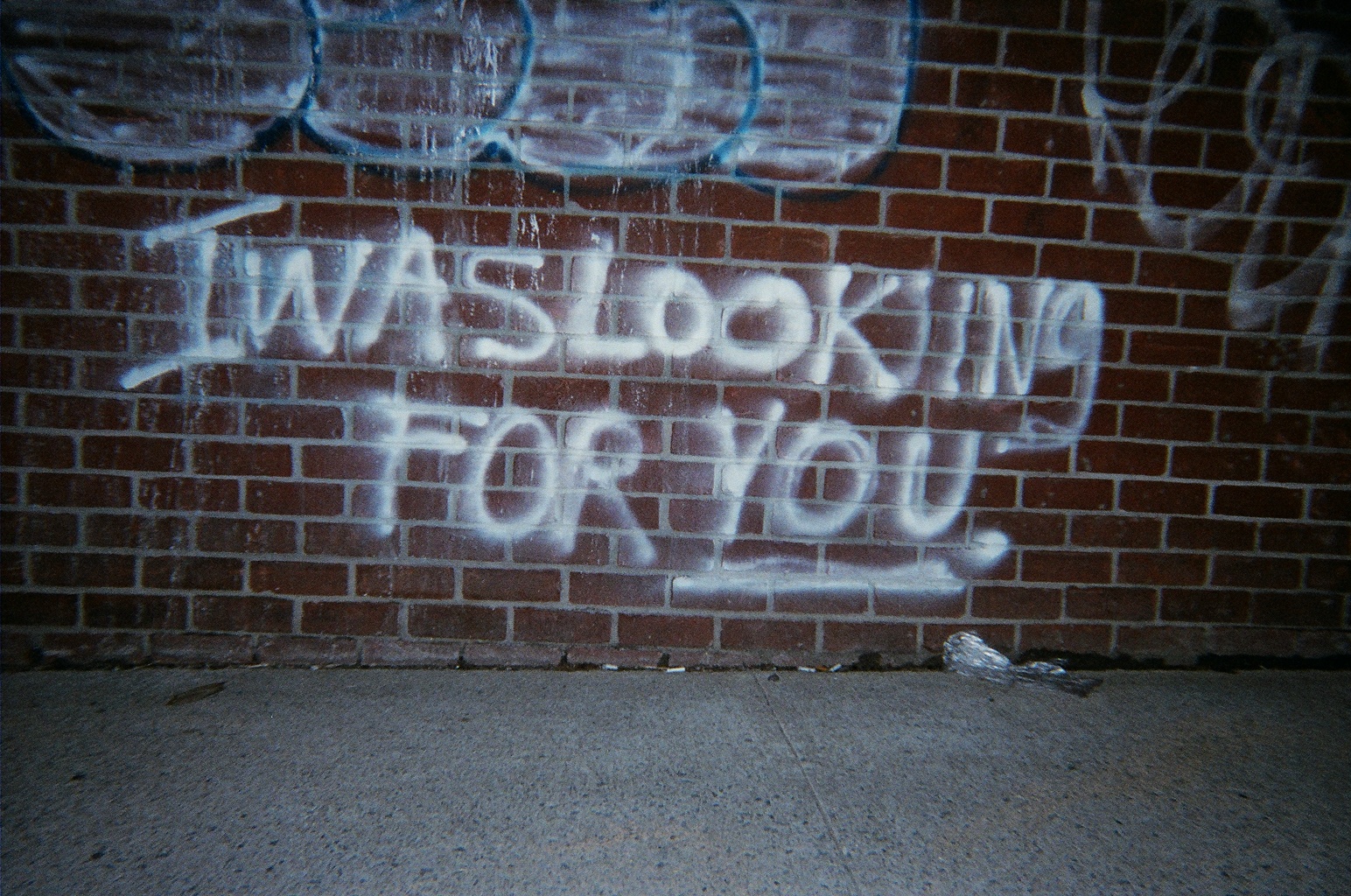

AR: It’s more open here. People are more curious. I like the way they think here. People just dare to do things. For them, doing things is experience. For me, that’s what life is about. It was nice to grow up in France, but people are not that positive. They are afraid to do things. Sometimes, the result doesn’t really matter at the end. Just go out and do something. In Paris, it could feel like a prison. I feel more open, more supported, and a bit crazier here.

AP: Is it your first time in New York?

AR: I’ve been going back and forth for a year. I wanted to know for sure where I wanted to settle. Sometimes, you have an idea of a city or a job which is not the real thing. I didn’t want to jump into an illusion. I was doing two months in Paris, a month here, two months in Paris, and a month here—for a year. If you move your ass in New York, you can really get somewhere. After the year, I knew I preferred it to France.

AP: What are you working on next?

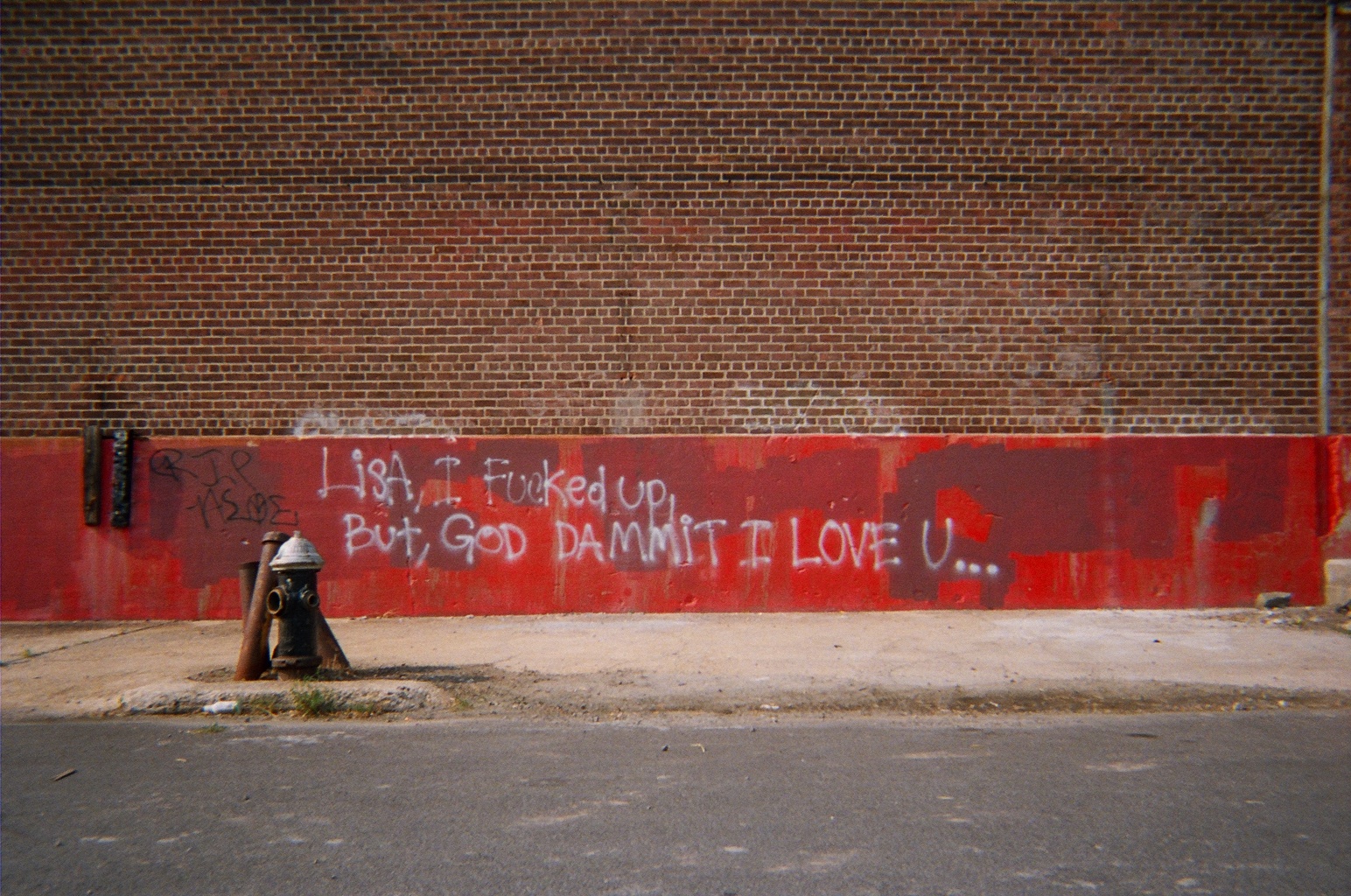

AR: I wouldn’t say I’m hoping to deal with more mature work, but the next thing I’m working on is much more frontal. It’s still my signature, but my art thus far has dealt with subtle, hidden messages. You can decode if you want to, but you have to plunge into it. The next piece I’m working on is super frontal. You can’t escape it. I don’t know what’s going to happen after.

AP: How did you come to do this new work?

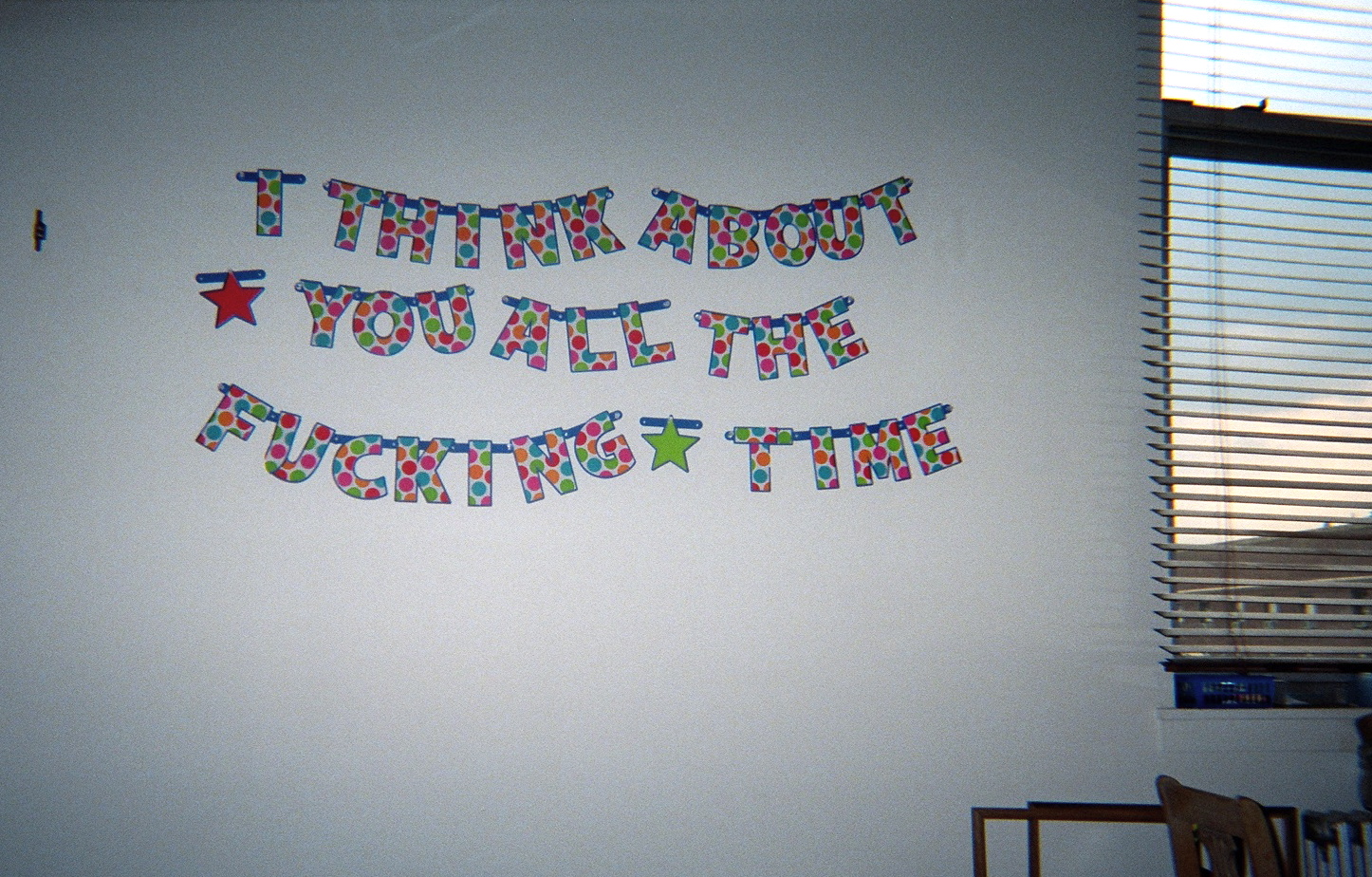

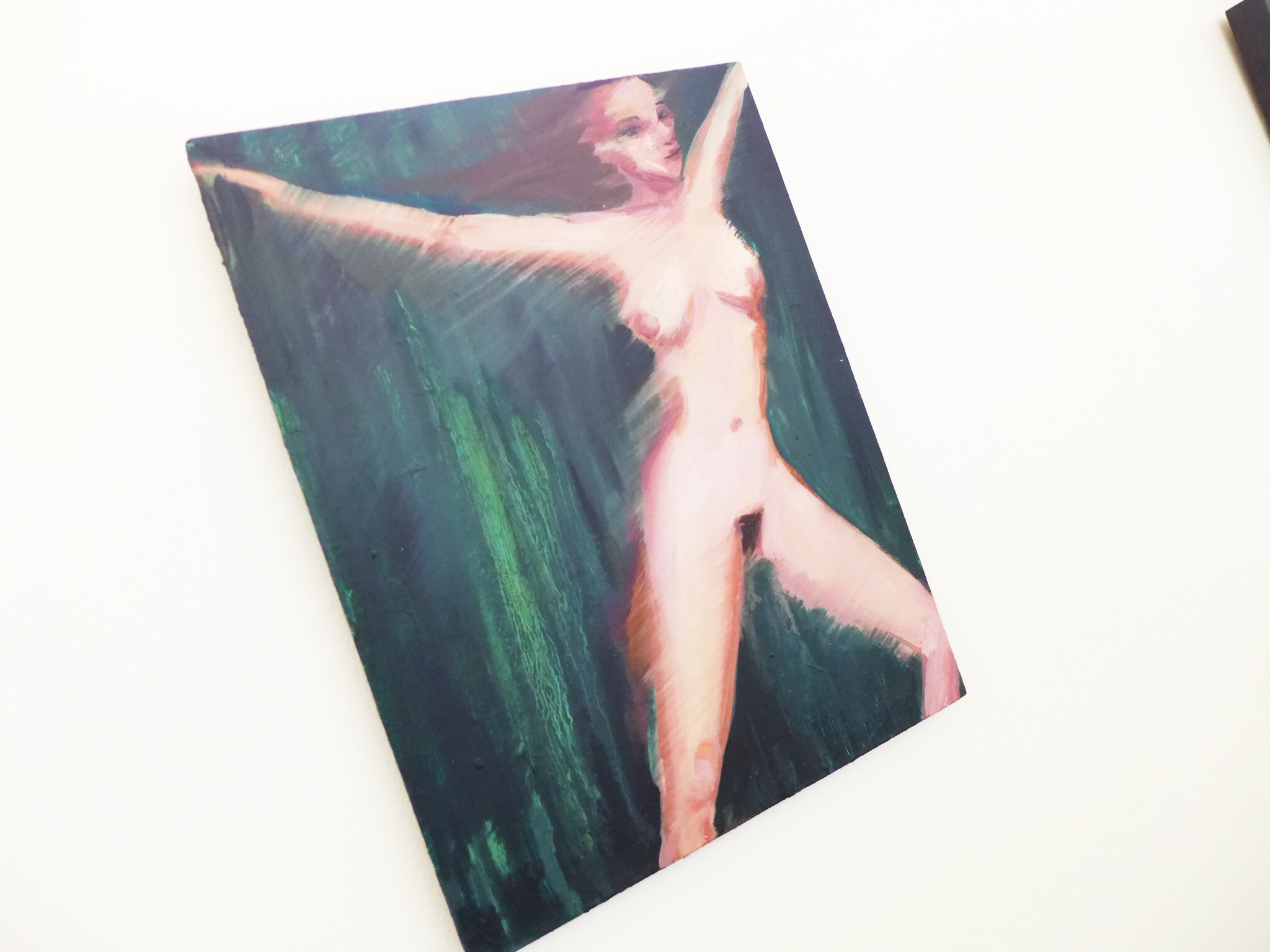

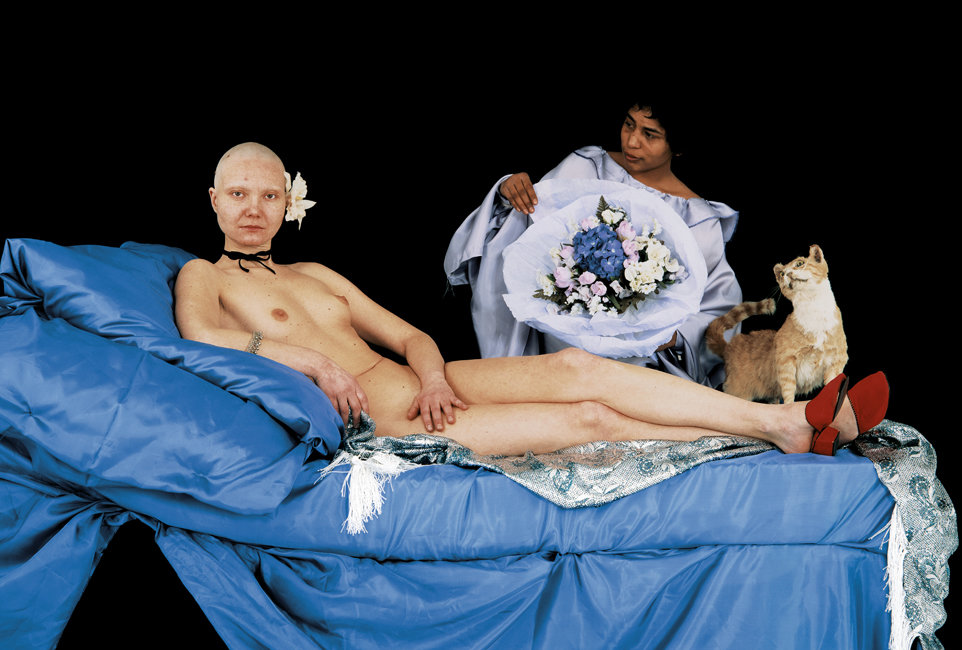

AR: The last one that I just finished—it’s called “A Love Story—is more subtle. It’s about emotions. I wanted to work on a topic called “Love.” It’s so cheesy. Everyone would want to vomit on it. But I wanted something both subtle and deep. Provocative things—nakedness, violence—they’re too easy. It’s super-subtle. Then, from that project, I wanted to do something more frontal.

The new thing I’m working on is called “The Exit Fairytale of Suicide.” It’s super hard-cut. It’s between black and white, hard and light. It’s still my work, but more frontal. The topic of suicide—you just can’t escape it.

"I write quite often. But when I was younger, I didn’t write a diary, I would write on my body. It’s the same thing—symbolism. It’s one sign that stands for a whole story."

AP: Are you focusing mainly on film now? Or are you still working with sculpture and photography?

AR: The photography always comes with the film. I really like to keep some moments of the film, for the audience. There are a lot of people that can’t buy video art. So I want to be aware of that. It’s nice to have a certain moment of a film that plunges you into the whole thing when you see it. So, when I do video art, my whole photography is based on the film. I really don’t like to do photography pure. In a film, you are more authentic. You’re not standing in a pose. The image is in the movement. For me, it’s a deeper photography than posing photography.

In terms of sculpture, there are going to be more museum shows, more installations that you will really have to walk through. I’m also creating sculptures that I integrate into my film.

AP: For your film and photography, is it always you as the subject?

AR: In the beginning, yes. When I was younger, I did some modeling. It was easy, because I knew exactly what I wanted for the images. It’s not about me. You’re like a tool, a transmitter. On “Pieta,” at that point, the easiest way to get what I wanted to convey was to use myself as the model. The movements are played in slow motion, but I didn’t want to edit the video too much. I don’t like to change my art in Photoshop or anything; I like to keep it as close as possible to the original film. It’s good when you’re aware of your body, and when you’re aware of the camera. For me, that was easiest.

For “What Are You Fishing For?” I would have loved someone to be in my place, but the water was, like, six degrees (about 43 Fahrenheit). You can offer to pay a model as much as you want, but if it’s not their project, they’re not doing it. I prepared for months—taking cold showers, reading up on those cult divers. I was psychologically prepared to do that.

This last film, I’m not in it. I’d like to be more and more in the back. But in a way, it’s nice when you have the experience in front of the camera. I can direct people better. I know exactly what I can ask them.

AP: You do a lot of humanitarian work. Will that translate into your new work? Are you planning on continuing that in New York?

AR: I would love to. I work a lot with autistic children. Every time I go to Paris, I still go to see them. I worked in a project in Berlin for street kids. I would still like to integrate my work into humanitarian projects. For the moment, I haven’t looked around at what is in New York, but I would like to do something.

It’s easy to do good stuff as well. It’s not always necessary to do something that is public. You can be a humanitarian all the time, in a way.

AP: Would you want your art to translate that to the viewer?

AR: My art has a lot to do with emotions in general, and I really try to keep it open for everybody. That’s the humanitarian side of it for me. I don’t like the “elite art” thing. I loved that in Paris, all the exhibitions had young people coming—13, 12, even younger. I really want to have an art that talks to everybody. On the other hand, I don’t know if there’s a day where I can really work in front of the camera with autistic children or with women’s rights. In a way, it’s in my work without being in my work, through my personality.

AP: You described your practice as a “social media practice.” Could you explain that?

AR: Actually, it’s a term that I would love to erase. It created a lot of confusion. “Social media,” for me, was word-by-word. “Social,” because I like to be in the social, humanitarian arena. “Media” is just the medium that I use. But “social media” as in Twitter, Instagram, whatever created so much confusion. I’m stepping back from the term, because it doesn’t describe my work as an artist.

AP: Tell me about your tattoos.

AR: I started early, when I was thirteen. I write quite often. But when I was younger, I didn’t write a diary, I would write on my body. It’s the same thing—symbolism. It’s one sign that stands for a whole story. Nowadays, I use more of the paperwork to describe things. When I was younger, I did it on my body.

AP: Did you design them all yourself?

AR: Most of them. I work with a friend who is a graphic designer in Munich, just so I can do it properly. I got a lot of inspiration from the Japanese artist Nara. I saw one of his images when I was five or six, without knowing anything about contemporary art. But it was always appealing to me—the side of the cute little girl paired with this more evil side. I loved the eyes with the stars inside—like the universe. There’s a lot of depth, even though it can seem childish. I love his art. He was a big inspiration for a few of my tattoos.

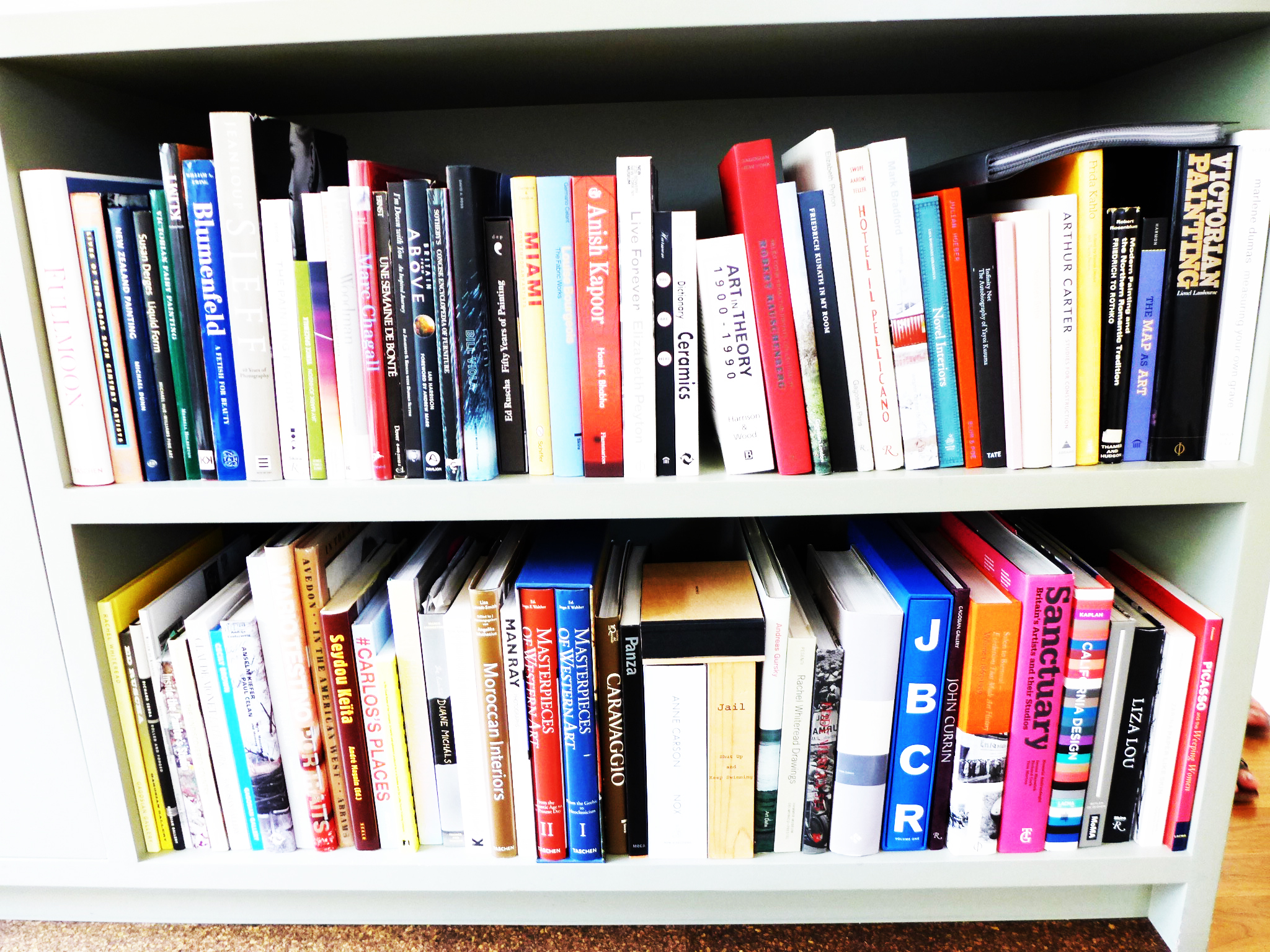

AP: Are there any artists specifically that inspire you?

AR: I like the paintings of German Romanticism—Freidrich, for example. I like literature as well. I love contemporary artists as well, but more for who they are. Marina Abramovic, for example. I’m not a big fan of her work, because it’s super violent. But I really like how she pushed herself to do something innovative and unique. She’s such a strong, spiritual woman. And her project, “The Artist,” is so great. Yes, nowadays, it’s a bit too commercialized, but I think she’s great.

AP: While you’re in New York, do you have any projects lined up besides the upcoming exhibition?

AR: I have a group show on the 22nd of November at Catinca Tabacaru Gallery on the Lower East Side. We’re about to talk about a solo exhibition there as well. I have two solo shows—one in Paris and one in Geneva—also in November. That’s the month. I’m working on other projects, but I’m waiting for confirmation before I spill any dates. The next show will probably be around springtime next year.

AP: Do you have a specific message that you want your new New York audience to get from your work?

AR: Not really. I think it’s not up to me. At the point that you exhibit your work, you give it up to people. It doesn’t belong to me anymore. Take whatever you want to take from it. I just hope that people will like it.

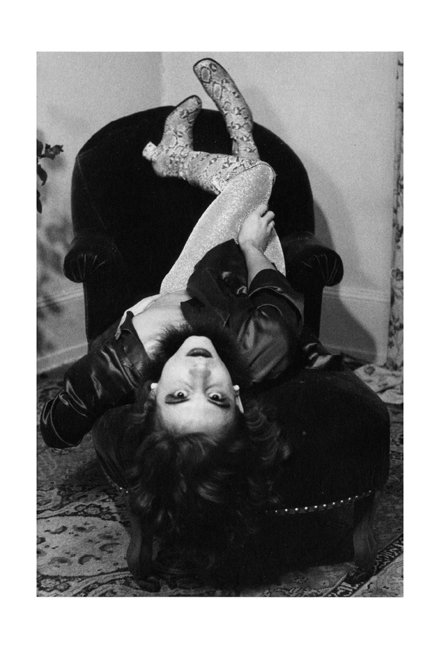

"What Are You Fishing For?" will open tonight and will be on view until December 1, 2015 at Elliott Levenglick Gallery, 90 Stanton Street, New York, NY. What Are You Fishing For? is also on view at the Venice Biennale until November 22, 2015 at Palazzo Bembo in the context of the European Pavilion. interview and photos by Adriana Pauly. intro text by Oliver Maxwell Kupper. Follow Autre on Instagram: @AUTREMAGAZINE