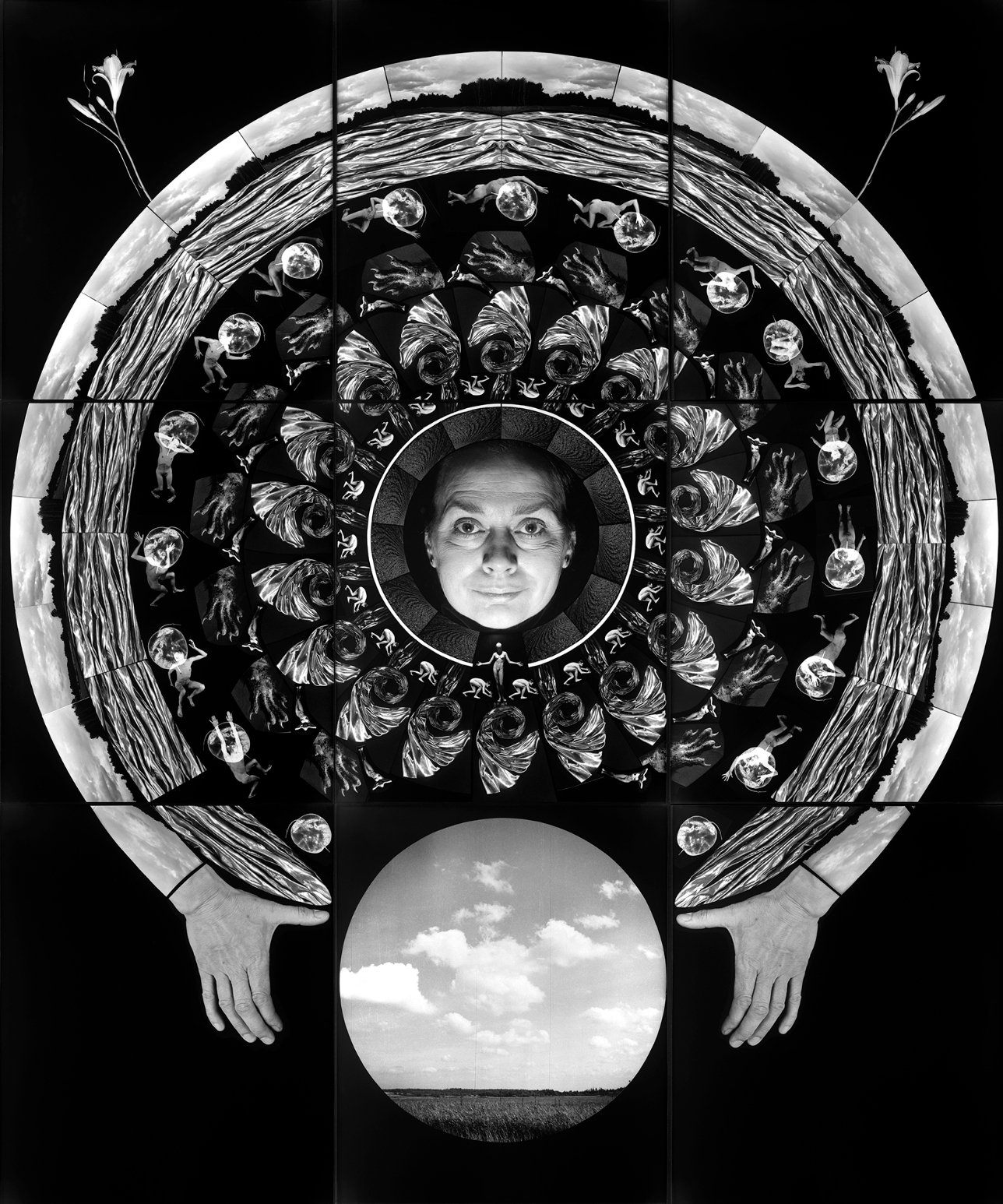

Larry Bell with Pacific Red II. Photography by Matthew Millman, San Francisco

For over six decades, Larry Bell has skillfully molded contemporary art in America. Born in Chicago in 1939, Bell moved to the West Coast to study at the Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles, the historic precursor to CalArts.

There, Bell became a member of Los Angeles’s Cool School, a rebellious group of artists, largely represented by Walter Hopps and Irving Blum of Ferus Gallery in the 1950s and ’60s, who brought modern-day avant-garde to the West Coast. Alongside Ed Ruscha and Robert Irwin, Bell is one of the last living members of the School. As a foundational figure in the Light and Space movement, Southern California’s take on Minimalism, which often employed industrial materials and aerospace technology to explore the ways that volume, light and scale play with our sense of perception, Bell made innovative work that experimented with the interconnections of glass and light and their relations to reflection and illusion.

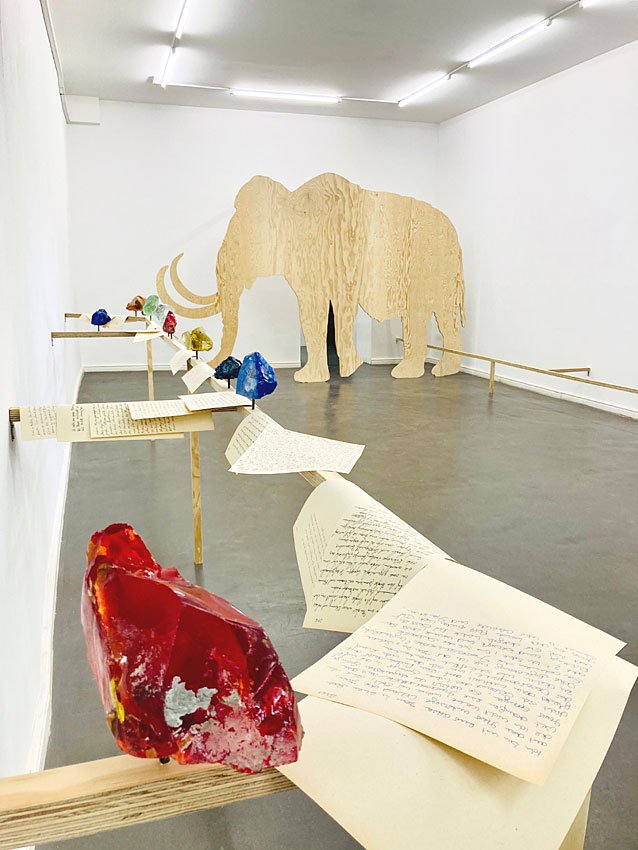

His most notable works involve his creation of semi-transparent cubes made out of vacuum-coated glass to form an immersive experience as the art melts into space. Recently, six of Bell’s cubes have been installed in Madison Square Park, where they will be on view until March 15, 2026. Improvisations in the Park carries on Bell’s legacy, but with a twist. Instead of their typical white cube environment, they have been placed outside to interact with the constantly changing elements, causing a new perception almost every hour.

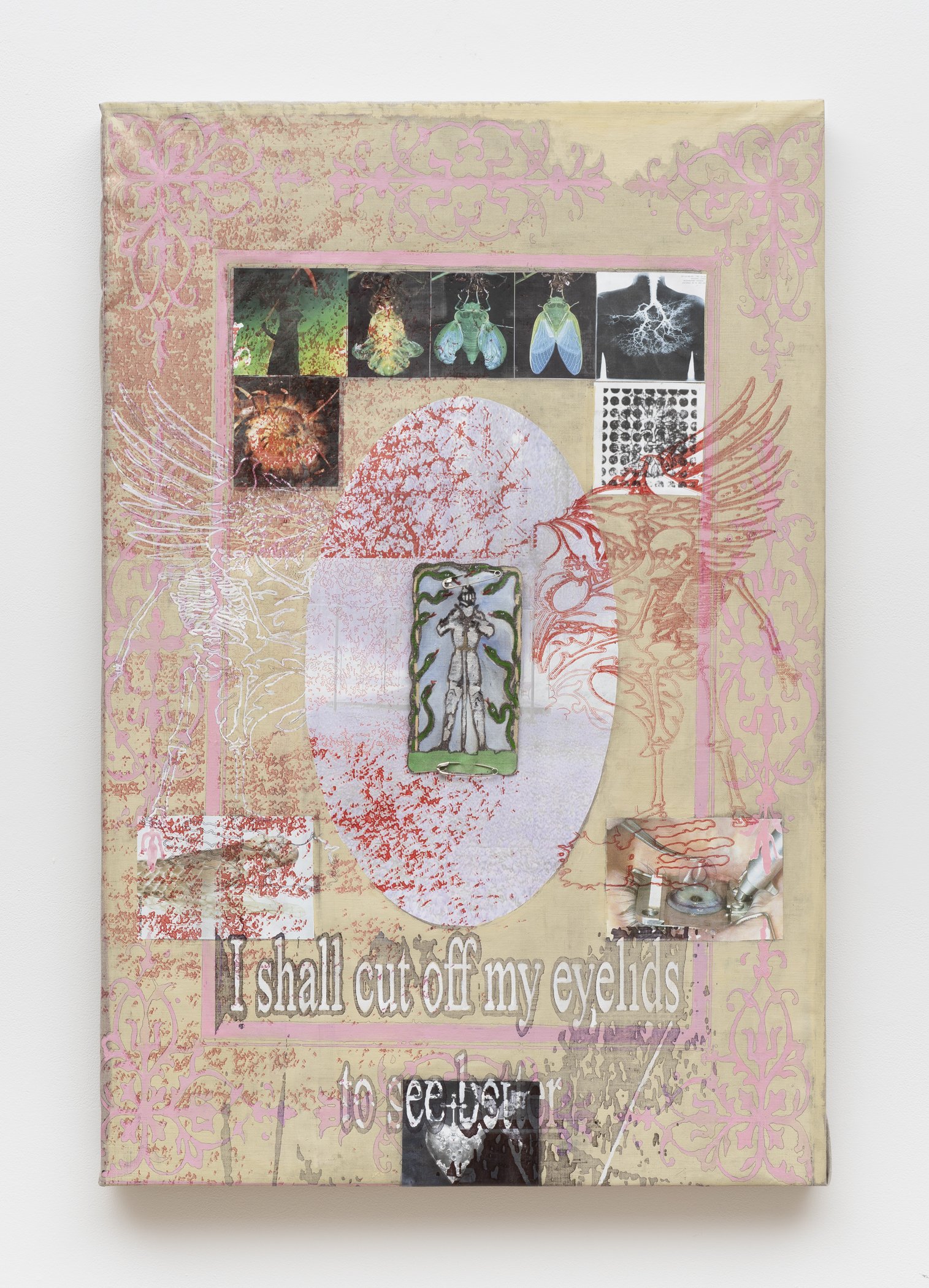

This idea, related to the flexibility of perception, is also highlighted in Bell’s recent series of collage works, Irresponsible Irridescence, on view now at the Judd Foundation in New York. These collages poured out of Bell after the passing of his wife two years ago, sharing a more emotional side of his work with audiences. They also subtly allude to the close friendship between Bell and the late Donald Judd. It was Bell who convinced Judd to build this now-historic organization in Marfa, Texas, rather than El Rosario, Mexico, impacting American art history forever. Read more.