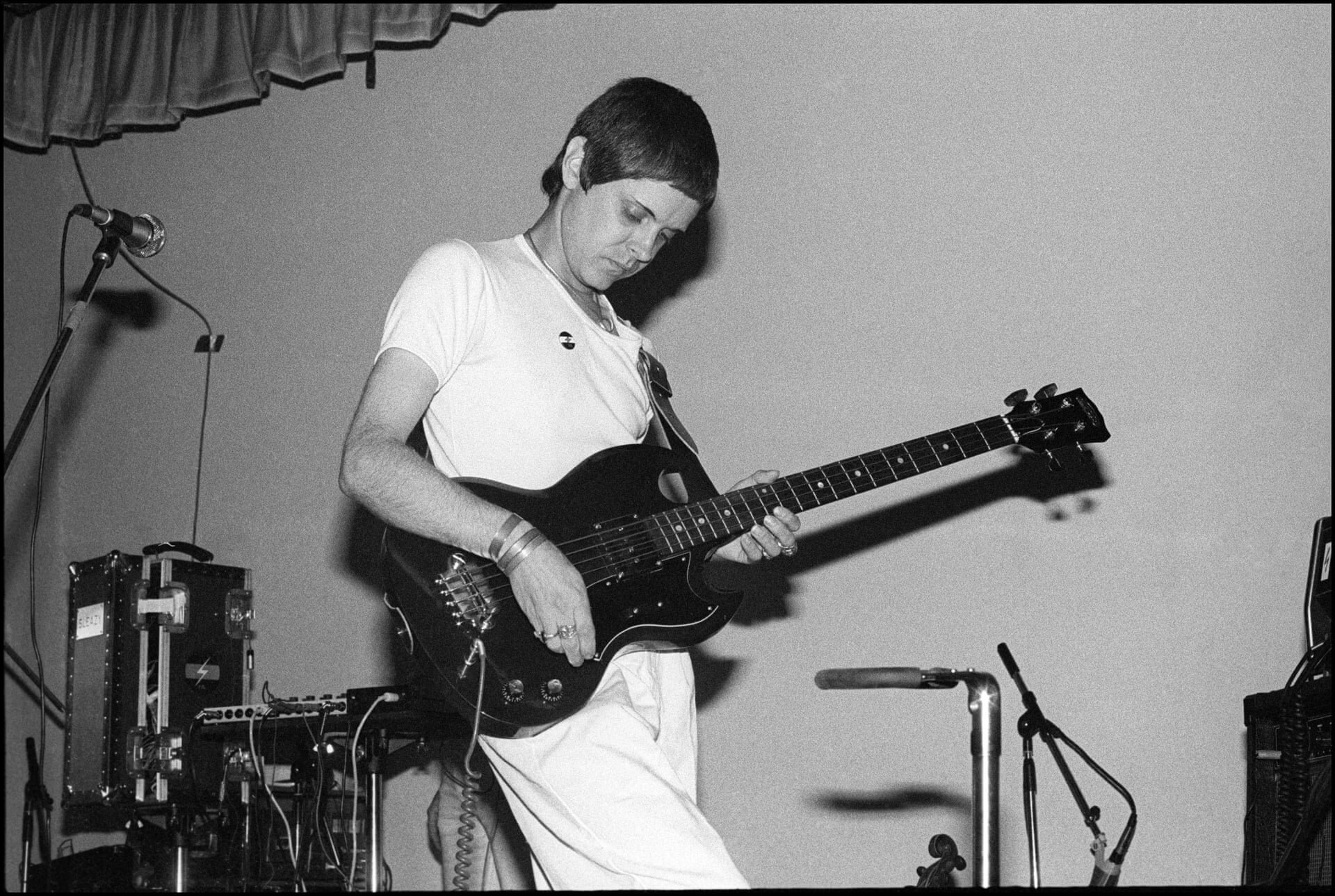

Brian Raymond

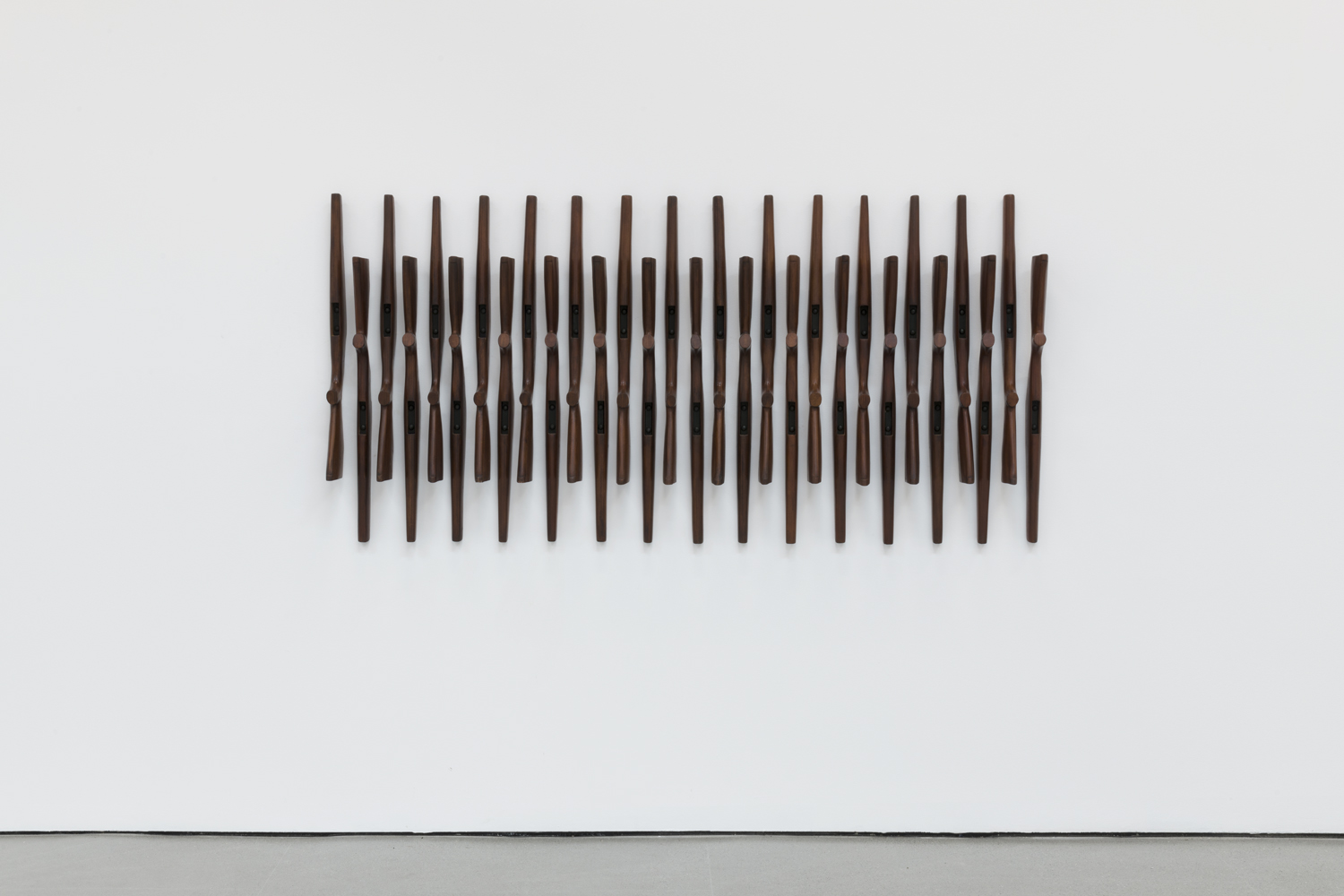

Tree Hollow Composition, 2021

Maple tree hollow strung with harp strings, processed thru OP1, eh95000, and Sponge Fork

Run time: 10:00

interview by Summer Bowie

photographs by Abbey Meaker

Is it in our nature to make art? Is art inherently ephemeral? Is there a boundary between art and nature? How can we look to nature as a blueprint for the art that we make? These are all questions that come up as I consider Land Chapters, the inaugural exhibition by Artist Field, a platform for projects that respond to and engage with natural environments. Curated by Estefania Puerta and Abbey Meaker, this exploration of the boundary between nature and self is a deep dive into the works of 16 artists split into three chapters. The first chapter is comprised of installation works that can be found deep in the woods of Richmond, Vermont on the Beaver Pond Hill Property. The second chapter comes in the form of a tape with recordings from six different sound artists. And the third chapter is a print publication with text from seven additional artists. All together, these works serve as an attempt to embrace all of the hard-to-pinpoint expressions of art within nature that so often fall under the towering shadow of negated space left by the Land Art movement.

BOWIE: How did the two of you meet and what was the inspiration behind Land Chapters?

MEAKER: I can't remember how we met, but I've known of Este and her work for years now. We live in a small community and her work has always stood out to me. We connected more deeply when I interviewed her on the occasion of her first solo show in New York. She talked about 'romancing wounds' and we discovered a shared obsession with psychoanalytic theory, specifically Julia Kristeva's work. More conversations about art and books led us to Land Chapters. She asked if I wanted to co-organize a show on her and her partner's land, and it seemed like the perfect setting for Artist Field's inaugural project. Collaborating with Este on this has been so natural and thrilling.

PUERTA: I became aware of Abbey through the amazing work she was doing with Overnight Projects. I wasn’t living in Vermont at the time and it was so refreshing and exciting to see independent curatorial projects that Abbey was doing from afar. It gave me hope that maybe Vermont could be a site of contemporary art and critical thinking and not just a place for hermits and landscape painters.

BOWIE: What can we learn from the Land Art of the 20th century, both positive and negative?

PUERTA: I think the Land Art category is vast and uncontainable in many ways, The overlaps tend to be that it involves earth materials that were traditionally unconventional to the art world at the time, a form of negation to the commercialization of objects and materials via their eventual decay or change in organic composition, exploration of spaces outside the white cube as sites for installations, and a questioning of worth/value in the materials used to produce art.

From these general standpoints, came so many different approaches. I think the Arte Povera movement paved the way for artists to open up their practice to the kind of multimedia, materially dense, and organically varied forms we see today. It has allowed bigger questions around how we deal with materials that are not meant to be controlled and it has continued the discourse around the boundaries of what we consider art and where we deem it to exist.

With that said, so many histories have been erased in the categorization of “Land Art,” as though these American men in the ‘60s were the first to create objects, installations, and spaces with earth material. Abbey and I really feel that addressing this kind of erasure and inherent violence to the way that white western art categorizes such a dense history with so many people, so many species, so many territories is a type of critical reckoning to anyone interested in contending with “Land Art” today. I’m not saying that we by any means filled this gaping hole with this exhibition, but rather that we quickly felt that attempting to categorize “land,” “nature,” “human relationship,” was in many ways at the risk of erasing and conflating something that truly feels uncontainable. And we felt it important to honor that murkiness and the wide web that it can create across people, instead of continuing to pretend that Land Art was a movement that mostly centered itself around cis white men performing heroic acts of intervention onto a vast landscape.

I think it is possible to address this movement and the ways that it subverted the art world, while simultaneously opening up the conversation about the erasure of many people, especially BIPOC, queer people, and women in its history.

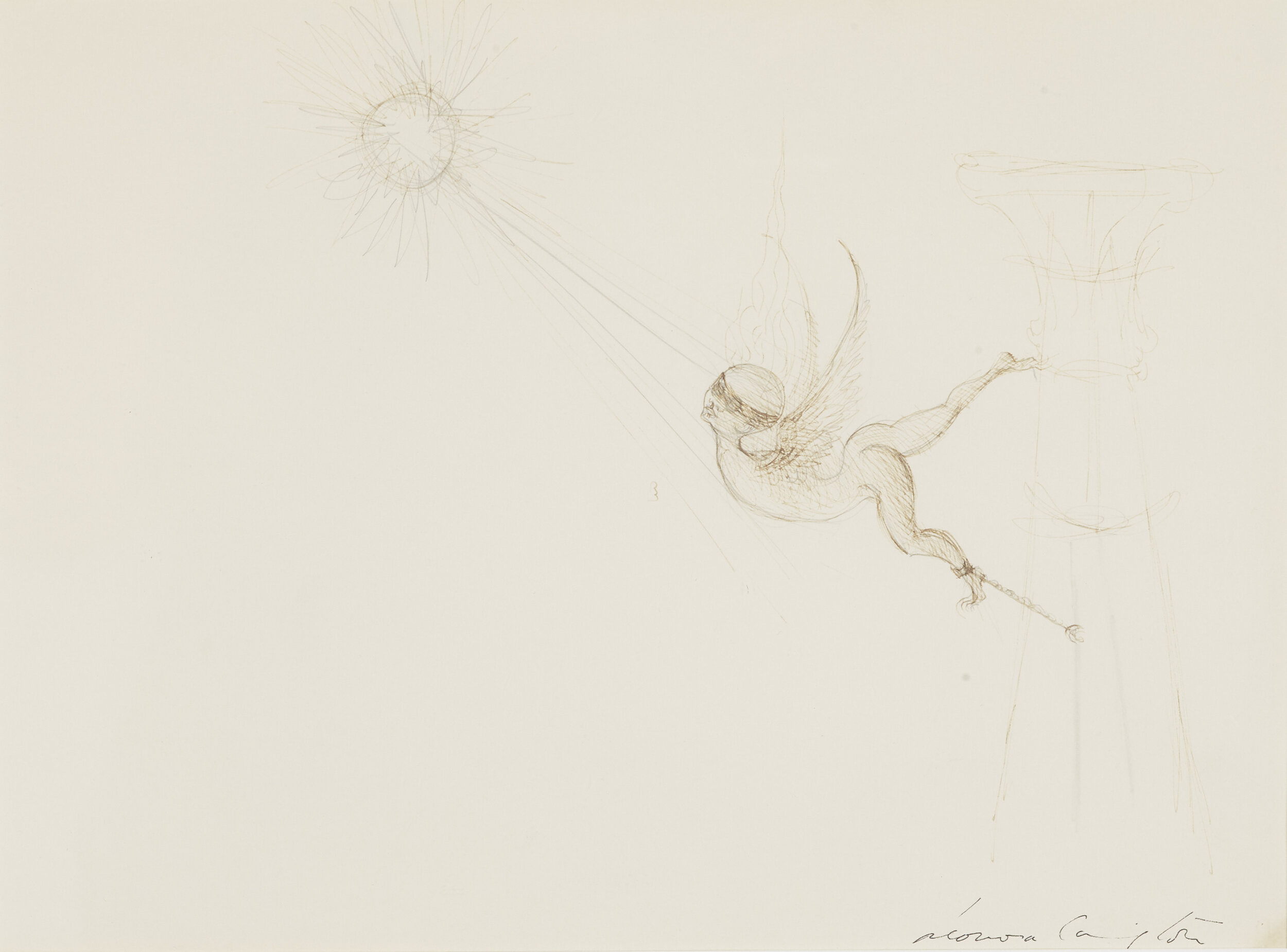

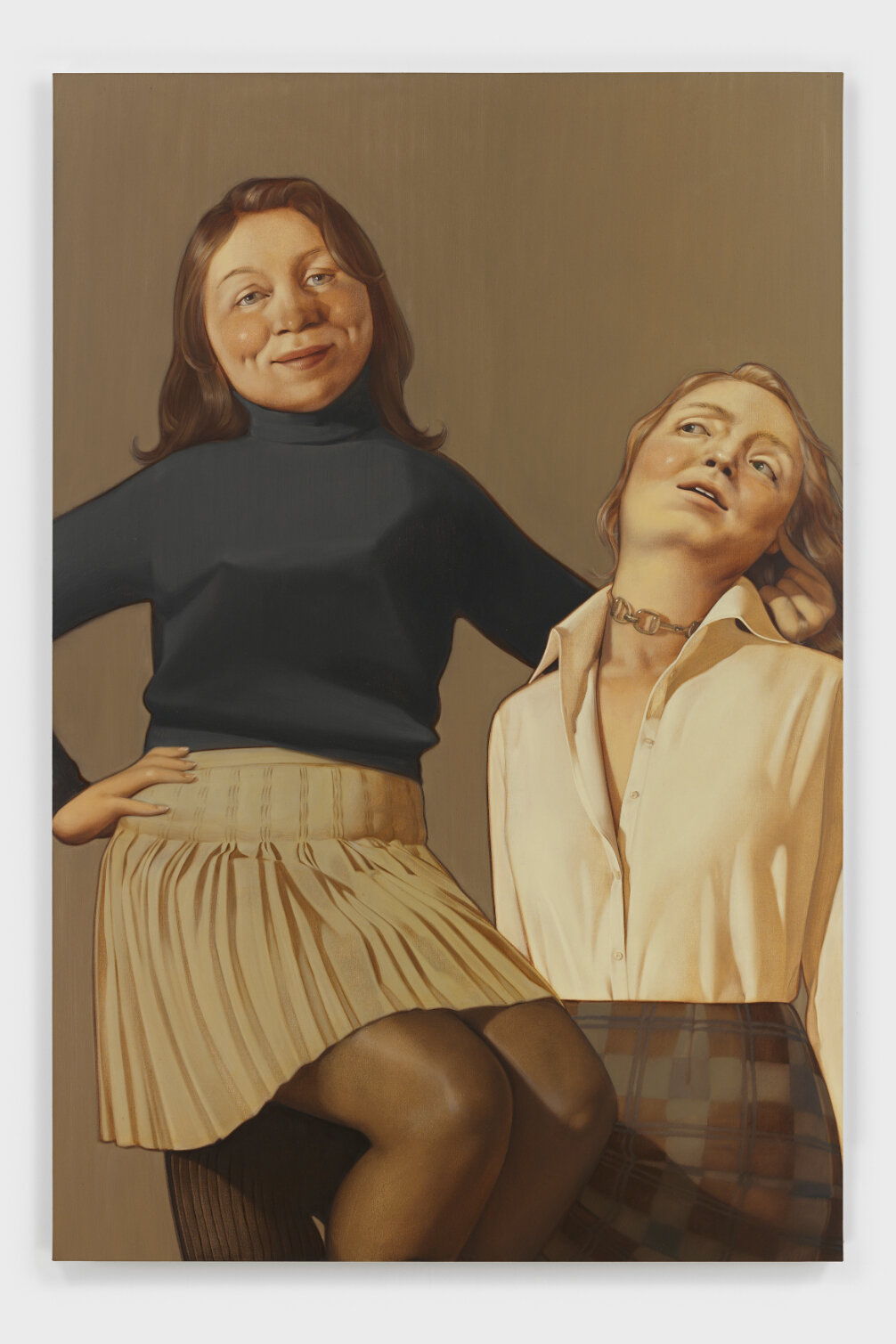

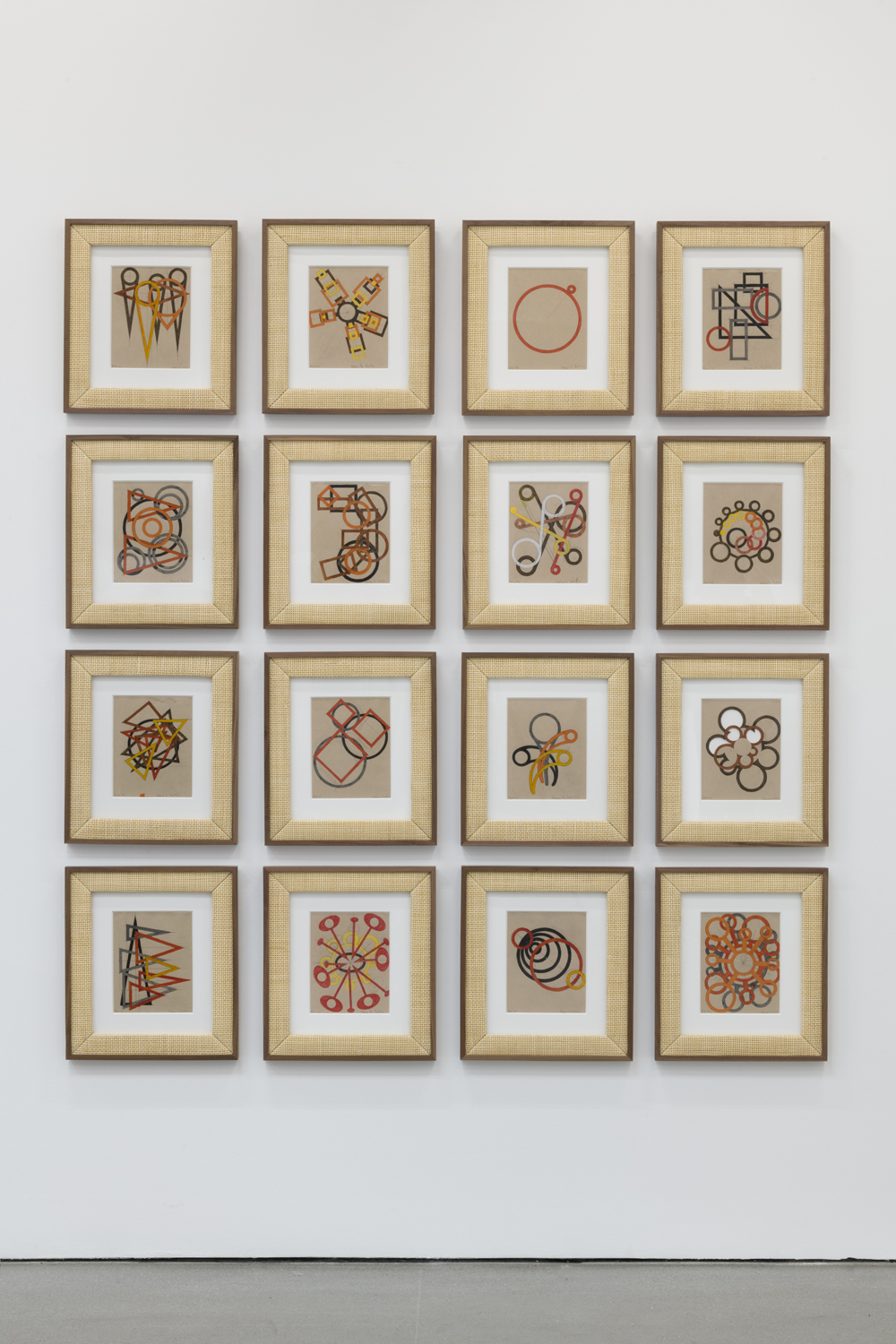

Lily Consuelo Saporta Tagiuri

Sun Belly; The Big Star That Feeds Us, 2021

Mixed wood scrap, aluminum, paint, and plaster

1.5 x 3 feet

BOWIE: This exhibition takes place on unceded land of the Abenaki Nation. How has their relationship to the land informed your approach to this project?

PUERTA: It didn’t and nor are we at all any authority to speak on behalf of the Abenaki people and their relationship to the land. We dedicated Land Chapters to the Missiquoi Abenaki in the humbled acknowledgement that they are the original protectors of what we call today, Richmond, VT where the exhibition partly took place. Our acknowledgement of their existence, of the fact that this land had been violently colonized and taken from the Missiquoi Abenaki does not give us any privileged insights or knowledge of their existence and continued ways of living on this land we call Vermont today. What has informed our approach to this project are the ways in which giving space and power to the different names and histories that a land holds feels like a more honest uncovering of the entangled and ultimately complicated relationships any of us have to what we call home, land, nature, history, relationship.

We look towards the histories here on this piece of land we are standing on as a starting point, as a way to say, “there is so much more here,” but we of course are not the arbiters of any culture and believe in the sovereignty of the Missiquoi Abenaki people to define their own terms and speak for themselves.

BOWIE: Both of you create work that explores your relationship to nature, but in very different ways. Abbey, can you talk a bit about that relationship and how it’s captured on film?

MEAKER: My work reflects a deep curiosity about atmospheres, the feeling or intangible qualities of a particular place, its history, the influences that inform it. How these mysterious aspects are connected to my own intangible spaces, memory, and sense of time. Cinema, photography—these are imaginative ways of seeing, of creating a dual sense of place, a feeling that within this world, there is another more illusory place. Curiosity about whether one’s interiority informs the atmosphere of a place and how it is translated visually. I work with film because of its materiality; it becomes a physical record of a time and place, absorbing the light and energy of a particular moment. For me, this primeval phenomenon is experienced most potentantly in the natural world.

In a more traditional sense, I’m interested in natural compositions found in forests, particularly floodplain forests, which I’ve spent the last year and a half exploring. Each year the rivers flood, and the trees are sculptured and re-sculptured by water, a knowable conducting force that influences the growth of the Silver Maples and Ostrich Ferns. A curiosity about the ways in which we influence and are influenced by ‘the land’ is at the core of my practice and of Land Chapters.

BOWIE: In contrast, Este, your sculptural works are made from a combination of natural materials and found objects. Can you talk about the role of nature as both subject and medium?

PUERTA: Nature in my work is about questioning what we deem as natural and alien, how our own bodies and earth can be our home and our prison, and all the slippery contradictions that nature holds. How it can heal us and kill us, how it both provides for us and takes us away. Nature has felt like the perfect archetype for the ways in which language fails us because language tries to hold clarity and structure in a way that nature cuts through and becomes excessive and complicated.

More formally, I am really interested in using that same kind of slipperiness to how we identify and name something and what its purpose can be. I tend to blur elements of nature both in its operations and appearance into body-like structures that also incorporate furniture materials, found objects, as well as more conventional art materials. These forms become proposals of bodies/environments that have evolved from the social ills of our world to become their own self-sustaining, migratory, empowered agents. They become their own worlds just as much as they become their own bodies. Nature is a reminder of how much we can adapt and how much we must protect ourselves.

BOWIE: What was the curatorial process like?

PUERTA: It was really organic and everything felt like it clicked into place so perfectly! It was a collaboration between Abbey and I, thinking of artists and writers who would lend a unique and important perspective around the curatorial prompt that was basically about addressing their relationship to nature in whatever way each person identified.

We had very little back and forth with the contributors and made it clear that we had complete trust in what they were making, and wanted to be open to their exploration. In our invitation we were explicit about the ethos behind this project being about a more gentle response and collaboration with the land around them, instead of the historic, heroic interventions and every artist we invited already worked within that ethos.

Letting go of a certain expectation felt important early on and embracing total trust and availability for conversations is a more natural way that Abbey and I work as curators. Both of us being artists, we intimately know the work and intention that goes into an art practice and the kind of freedom and support that is needed to nourish that practice.

At the end of the day, we love artists and wanted to make sure our contributors felt that love and support. I think that is important to say, because often a show solely focuses on the type of work an artist makes, or why they make it, but how is that artist doing? Are they feeling supported in their practice? Are they truly being valued? How do we make the curatorial process one of support and not one of extraction for the artist? There are so many behind-the-scenes dynamics, and so often artists are the ones that suffer the brunt of a lot of hustling and feeling slightly demeaned along the way. Our process was slow, deliberate, immensely grateful, and apologetic if we felt a bump on the road. And we feel that that deliberate intention is felt in the project. Of course, every artist and writer contributed something that far exceeded any expectation we could have.

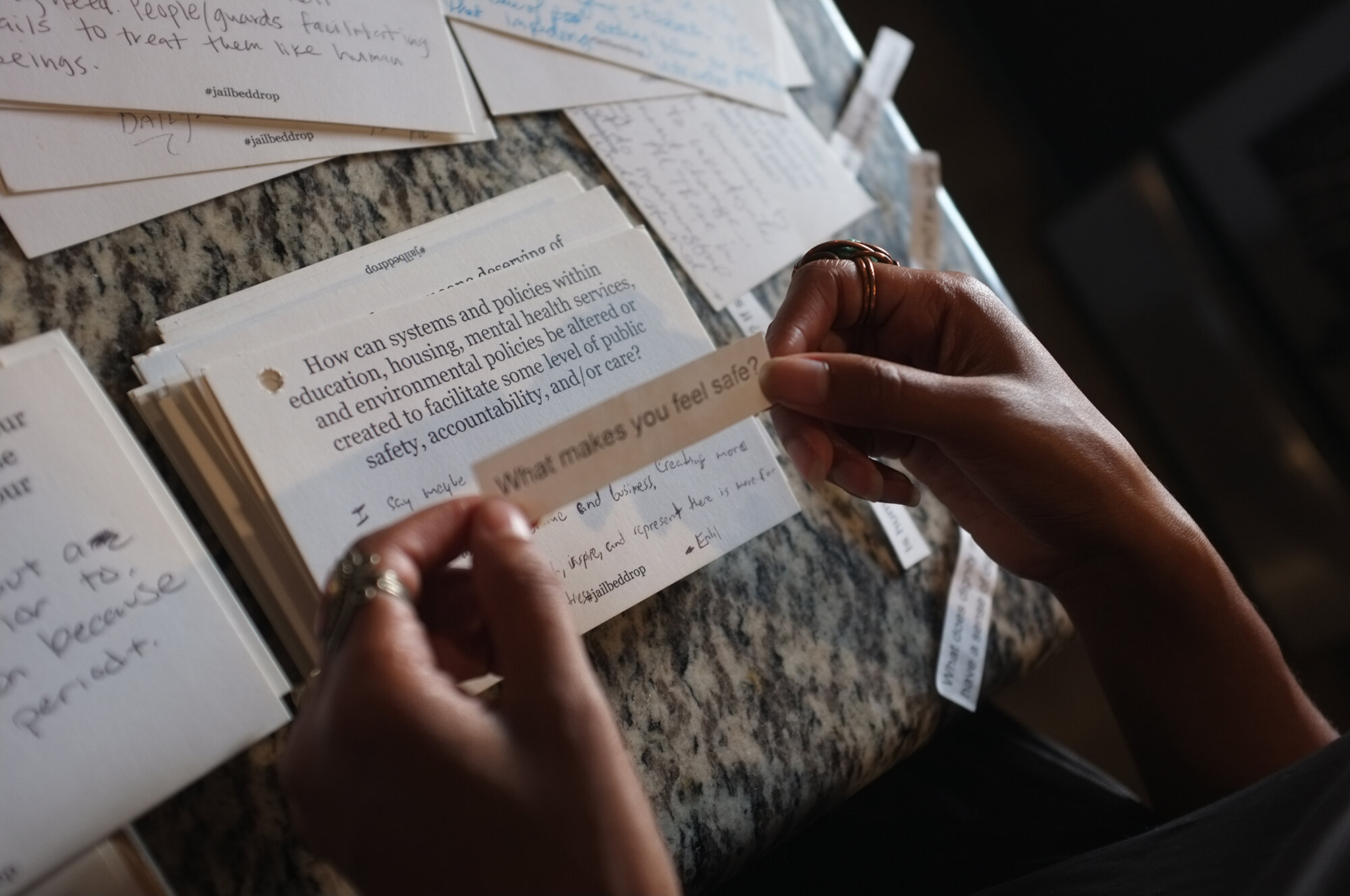

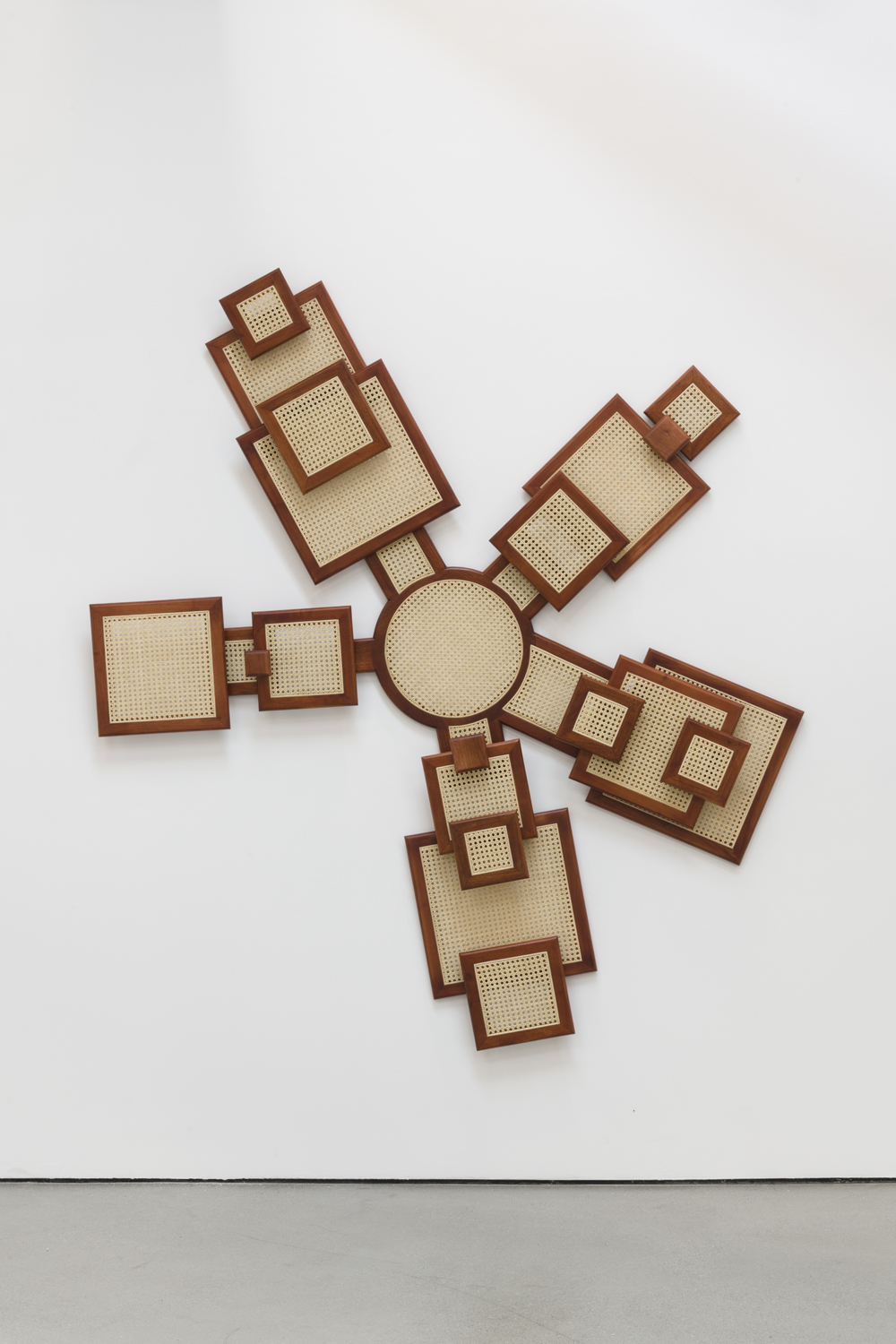

Enacted prompt from Angus McCullough and Ashlin Dolan

Contact Kit, 2021

Birch bark, grape vine, stone, moss, typed instructions in a plywood case

20 x 16 x 6 inches

BOWIE: There’s such a multi-sensorial aspect to the curation. Works that you can see, hear, smell, and taste. Was the sensory aspect something you were considering in the curatorial process?

MEAKER: There’s something about being outside in a natural setting that attunes our senses to the world around and inside us. We wanted the experience of the work to reflect this. To attempt to communicate that we belong to this place; it doesn’t belong to us. We are part of this vibrant ecosystem, not separate. This is the throughline of Land Chapters.

PUERTA: And yes! So many senses involved. Lily Consuelo Saporta Tagiuri contributed Sun Belly, a functional solar oven and artwork that beckons us to collaborate with the sun as our main source of heat and cooking potential. Recipes were also contributed by Lily and will be included in the Land Chapters publication. We will be baking sun bread in the oven and offering it to visitors.

The sound pieces will have their own designated listening spots scattered around the property where you can hear the sounds inside trees, a cabin, in a hole in the ground, and within the ferns.

The writing pieces in the publication also hold many senses. Sonia Louise Davis contributed a score to be performed by anyone anywhere, which is rooted in deep listening and feeling yourself in a space. Honestly, each piece beckons a couple of different senses at once, and I echo what Abbey said about just being in a natural setting; your own body is a heightened orb of senses where the heat of the sun will emphasize the smell of the chanterelles and the echo of a sound piece in a tree feels like a distant howl.

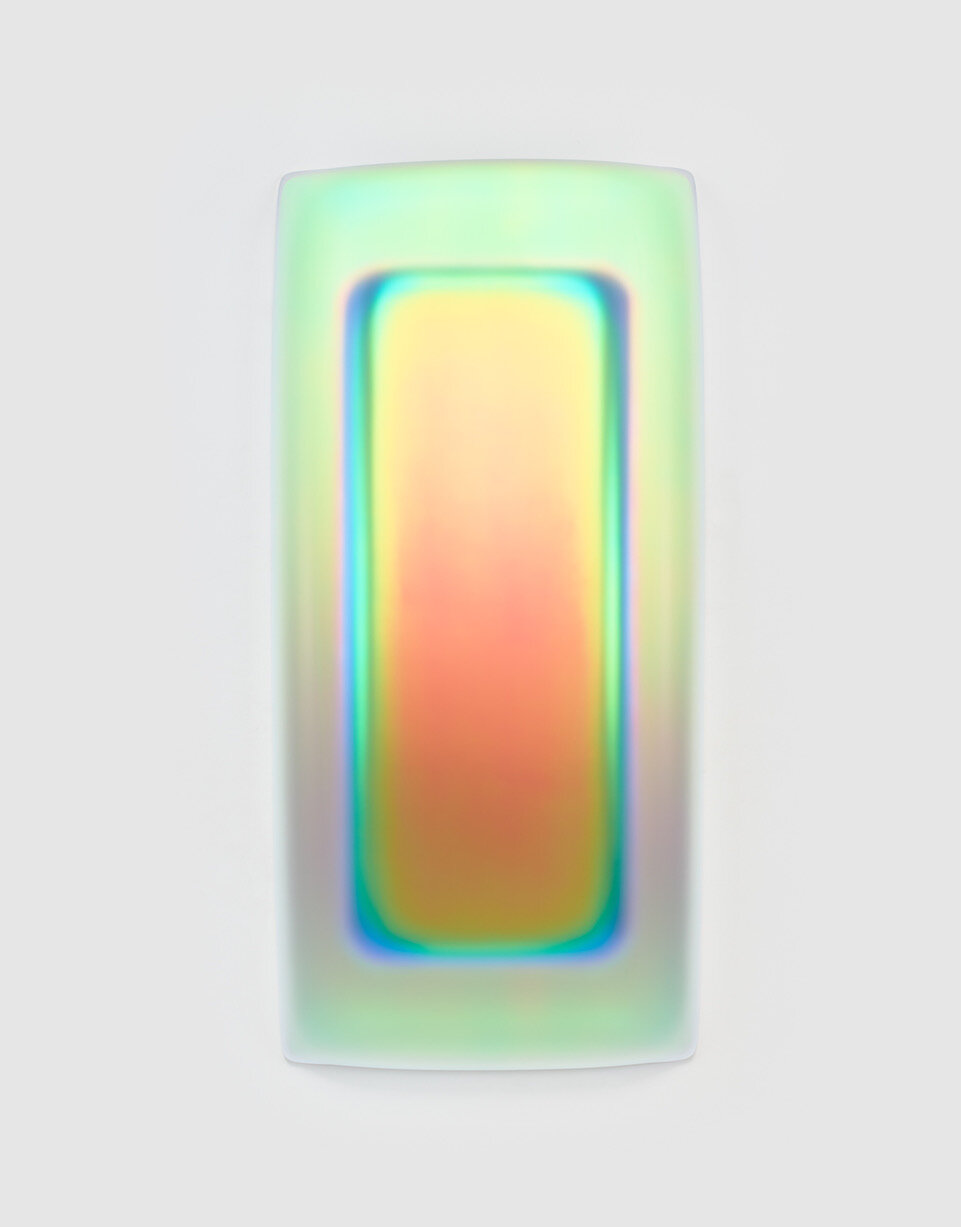

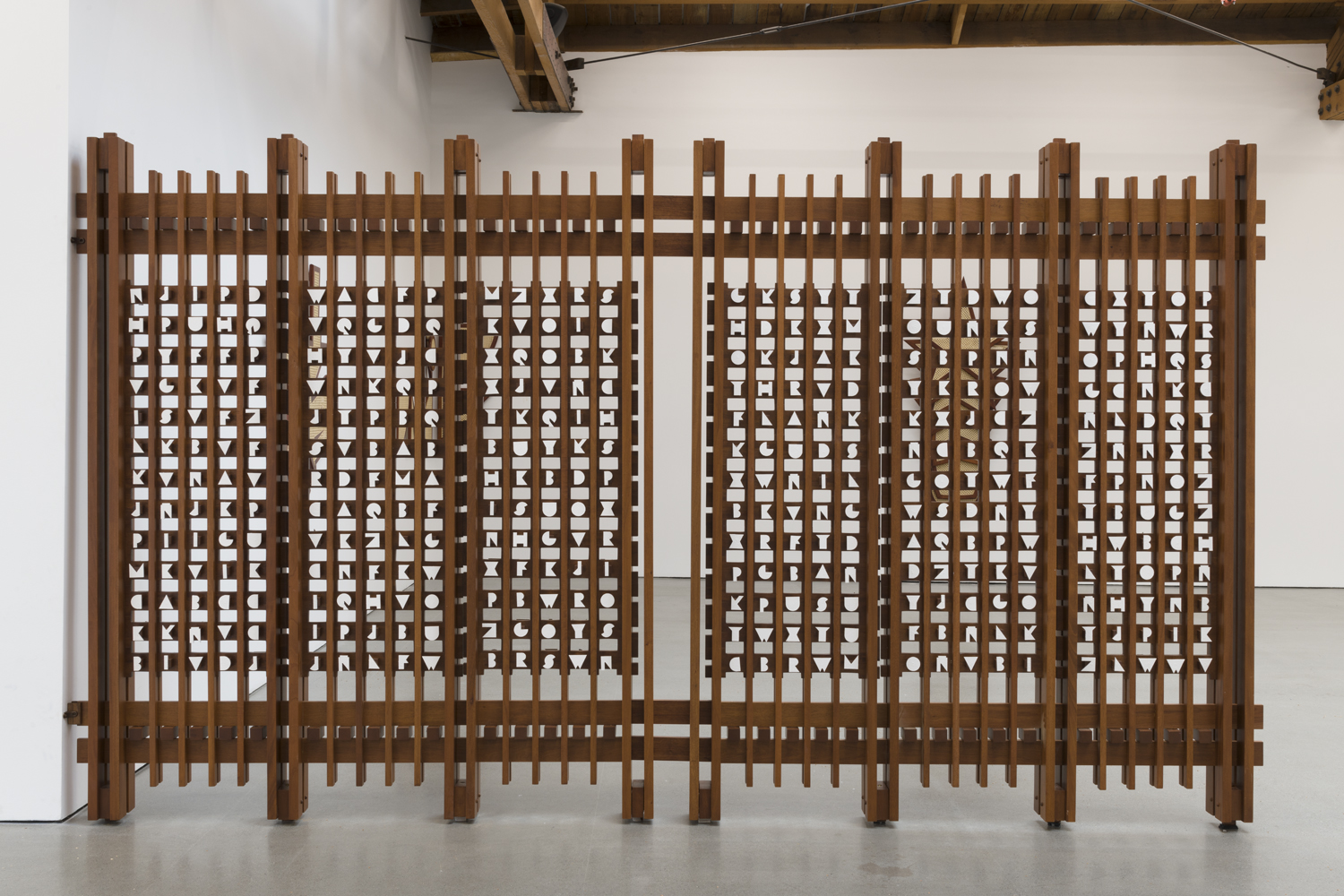

Jordan Rosenow

Four by Eight, 2021

Galvanized corrugated steel, rebar

4 x 8 x 4 foot units (dimensions variable)

BOWIE: Abbey, you’ve curated and presented work in a number of untraditional locations. I’m thinking about a former coal plant, a former orphanage, an airstream turned library, a corn field on the cusp of reverting back to a wetland. Why eschew the white cube?

MEAKER: I have nothing against the white cube, per se. It has its place, particularly in a commercial sense. I can appreciate that in this setting the work has a clean platform, visually and conceptually. But I am personally interested in and excited about ephemeral, experiential artworks, when the setting creates a larger context and more holistic experience.

The first show I ever organized was in the orphanage you mentioned, An Order. I had spent three years exploring and photographing this space, which had sat untouched for 30+ years. My maternal grandfather and his brother lived there in the 1920s. I never met either of them, so the process of being in this space was a way for me to piece together an unknowable history through the act of making pictures. At the end of my time there, I was curious how other artists might respond to this place: what would their line of thinking be if they approached it with more critical distance than I had?

BOWIE: What are the challenges and benefits that come with presenting work this way, as opposed to hanging a frame on a wall?

MEAKER: In this case, working in the woods, a half mile up an old logging road, we mostly had to contend with the elements; the changing environment informed the timeline and many of our decisions. We started planning this in January when the land was inaccessible with snow, and now, within just a couple of weeks of sun and rain, the ferns have unfurled and everything is wild and lush. One of the most meaningful aspects of Land Chapters has been connecting with this place in such an intimate way, coming to really know and see it change over seasons.

And the challenges have less to do with location and more to do with the lack of institutional support, especially here. It’s a real hustle to organize a group show like this, to navigate the logistics of a unique site, insurance and liability waivers, fundraising to pay artists, designers, promotion etc. If you don’t have enough support, much of your energy, attention, and resources are going to the mechanics of the exhibition. It becomes more challenging to balance curatorial responsibilities with organizing. I don’t know that I’d have it any other way, though. It allows us a certain freedom, as we are not beholden to donors or collectors. Artists can experiment and push their practice in ways they may not have otherwise. All that said, we have been so lucky to have a tremendous amount of community support. Friends and colleagues have generously donated their time and talent to help with design and aspects of organizing that two people simply can’t manage on their own. It has truly been a collective effort.

PUERTA: We had to think about nature as our collaborator and saboteur. Ruben Ulises Rodriguez Montoya’s work, for example, has a sculpture that is made of cat bones and we have to be very diligent about when it is installed and when we must bring it back into the cabin because a coyote or other animals would absolutely destroy it. Not to say that Ruben may not be interested in this potential collaboration, but it does become a question of how do we protect the intention and how much do we allow our surroundings to take over, and each work addresses that differently.

Ruben Ulises Rodriguez Montoya

Tres Tristes Gallos pa el caldo de las tres de la tarde, 2021

Yucca husk. All sourced material from the Rio Grande River, in an area that borders; Texas, New Mexico, and Juarez, Mexico.

We have another artist, Devin Alejandro-Wilder who uprooted a cacti cluster from Texas and sent it to us to be transplanted in the woods of Vermont. With their piece, it was very much the intention to actually root a non-native plant into the soil of Vermont and see what would happen, see how much care and maintenance it would need, see how it would respond to its new surroundings and how its new surroundings would respond to it. So much of Devin’s piece is about this type of migration and otherness that occurs when introduced to a new space, a new territory that has been historically deemed as “unviable” for you. So, we document their piece often, notice how it changes and adapts, and are mostly humbled by the resiliency of this plant and the symbolism it holds.

BOWIE: This project is a lot more expansive than just an exhibition. There are installation works on view, a book, and a tape of field recordings. Ultimately, what do you want people to take away from this work?

MEAKER: We see Land Chapters as one exhibition, experienced in three unique spaces, or chapters: installations on the land, the book, in which there are contributions from artists who are not part of the installations, as well as the tape of sound works. They are all connected by the curatorial prompt Este and I provided, but are unique spaces experienced differently, with different senses. For those that are able to experience this project, we hope it finds its way into your own relationship with the world(s) around and within you.

Devin Alejandro Wilder

T R A N S P L A N T, 2021

Nopales/ Opuntia engelmannii var. Lindheimeri, soils (native and mixed), pea gravel, rocks, cardboard

36 x 36 x 50 inches

Land Chapters is on view June 4-6 @ Beaver Pond Hill Property in Richmond, VT. Contributions to the exhibition include installations by Devin Alejandro-Wilder, Angus McCullough, Ashlin Dolan, Ruben Ulises Rodriguez Montoya, Jordan Rosenow, and Lily Consuelo Saporta Tagiuri; recordings by sound artists Wren Kitz, Ivan Forde, Brian Raymond, and Stephanie Wilson; and text by Chief Shirly Hook, Alan Huck, Wes Larios, Travis Klunick, Sonia Louise Davis, and Rachel Vera Steinberg.