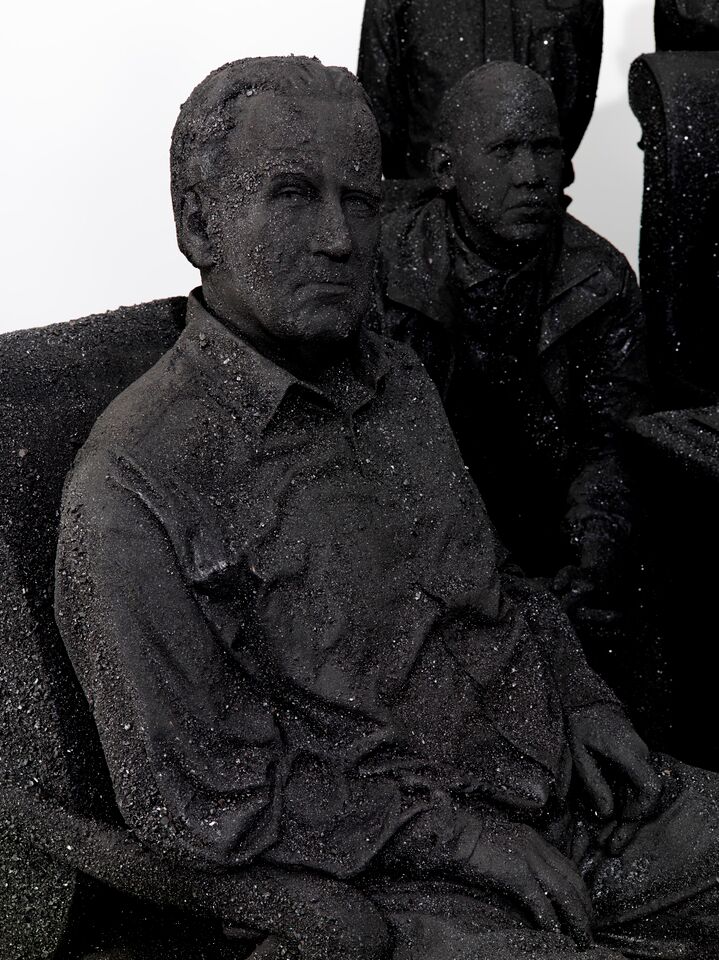

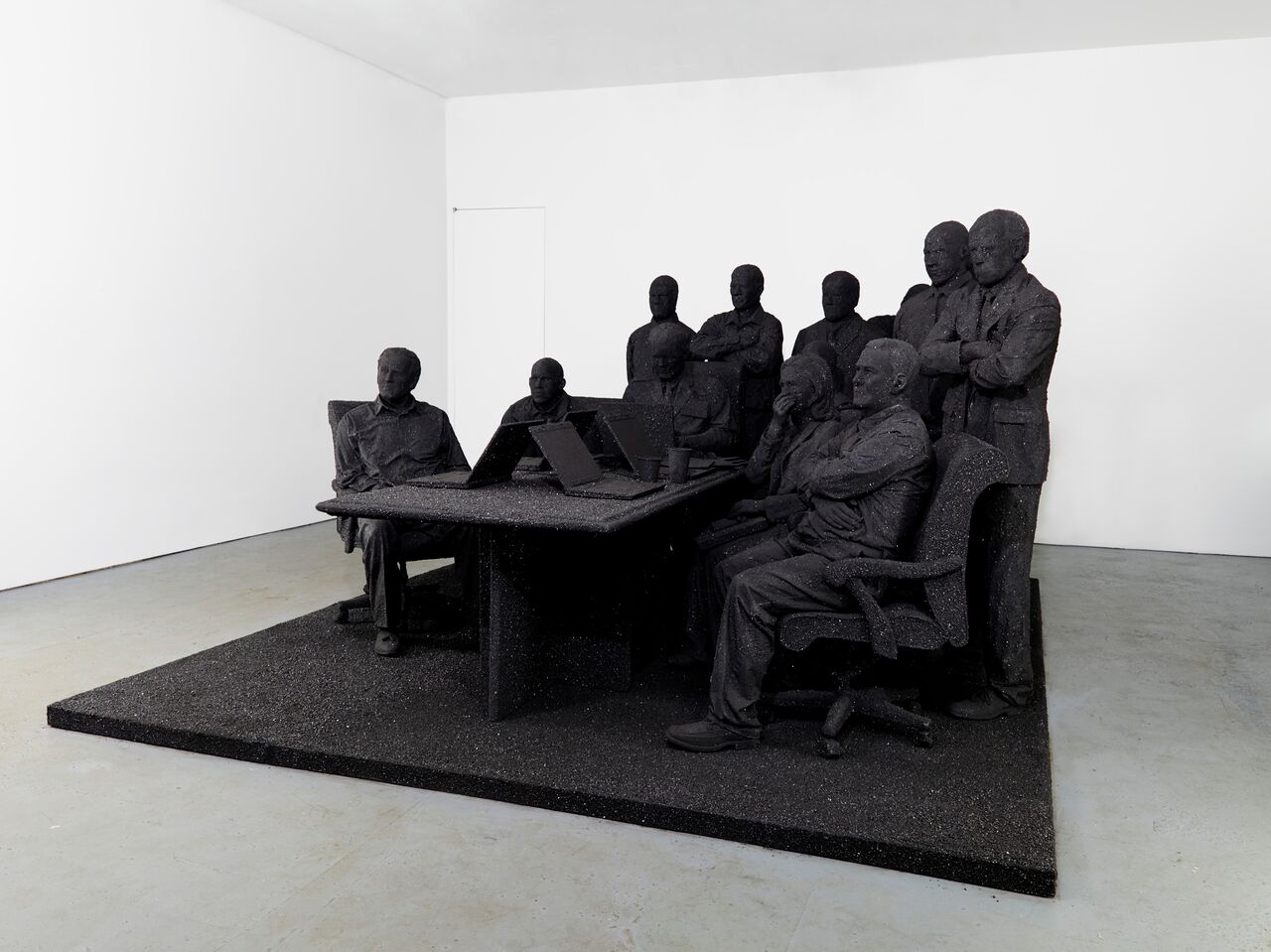

The Haas brothers seem like mystical ambassadors from the future. However, they are not here to portend of doom and gloom, like the current headlines may lead you to predict. Indeed, the future looks pretty bright according to Nikolai and Simon Haas – fraternal twins who make high-end sculptural objects that only the very lucky can afford, but are almost talismanic in their complexity and humorous in their intentional simplicity. The materials the brothers use mimic natural and rare phenomena in nature. This gives their work a sexual energy that takes phallic and vaginal forms, replete with folds and shafts and rounded curves that could make the prudish contingent quite sensitive. Put the work together and it looks like a combination of Maurice Sendak's menagerie of Wild Things and Dr. Seuss on too many tabs of acid.

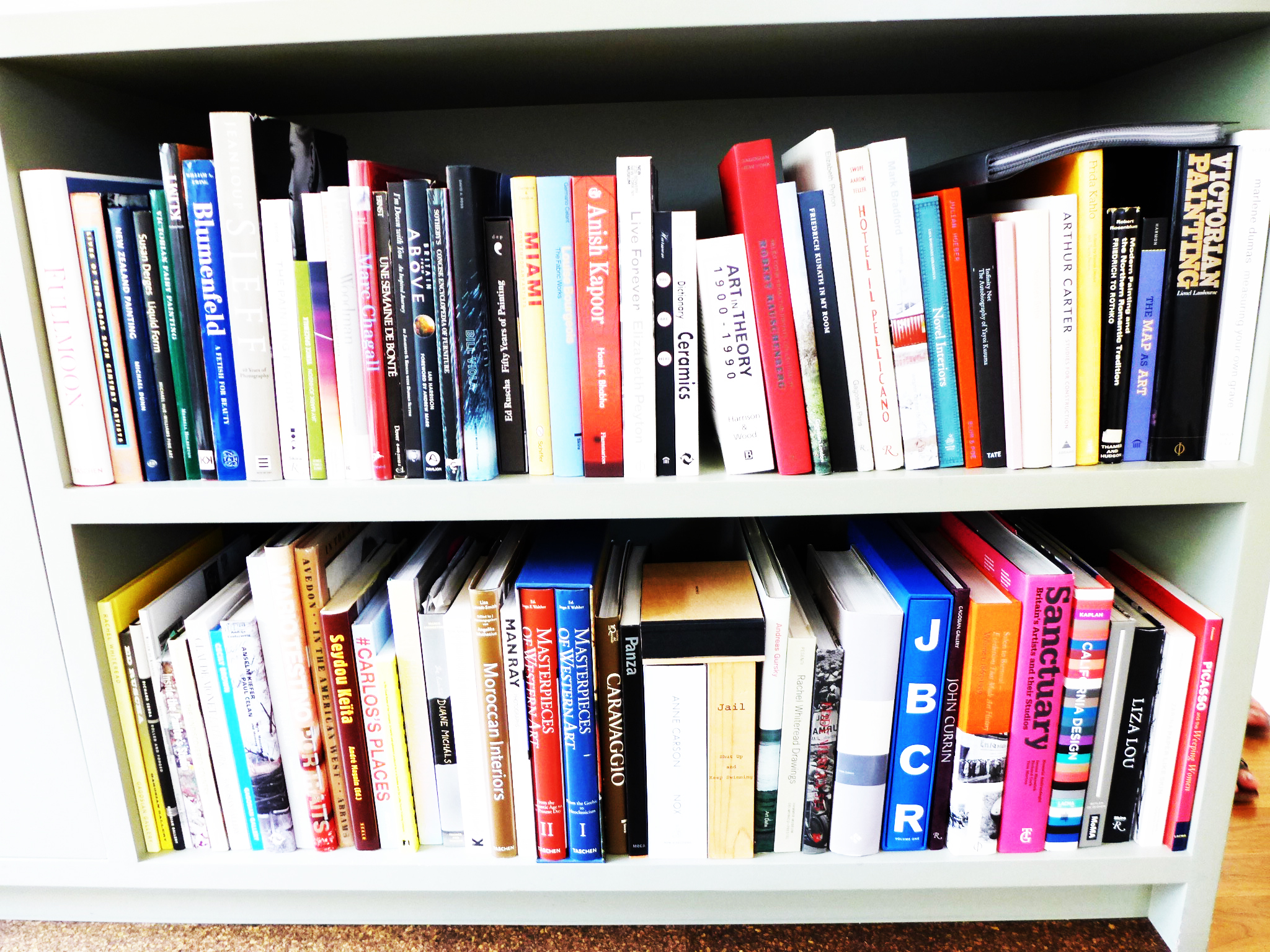

If you visit the Ace Hotel in Los Angeles, you can see some of their drawings on the walls of the Chapter Restaurant; next to the lobby. Portraits of Roman Polanski are juxtaposed next to chubby line-drawn creatures holding cocktail glasses – Nikolai’s work is more cartoonish, one dimensional and comical, while Simon’s work is more realistic, detailed and has more perspective. It’s a perfect way to experience their work on an individual scale. But it is when they bring their styles together that the real magic happens. Simon comes from a much more logical perspective, while Niki is much more laid back, creating an incredibly powerful dynamic.

Over the last couple of years, the Haas brothers have been riding high on a wave of popularity – a collaboration with Donatella Versace took their works straight to the gilded living rooms of the fashion and design world. Solo exhibitions in New York have made them darlings in the art world. However, the proverbial wave crashed when they were on a private jet heading back to LA from an exhibition of their work in Miami.

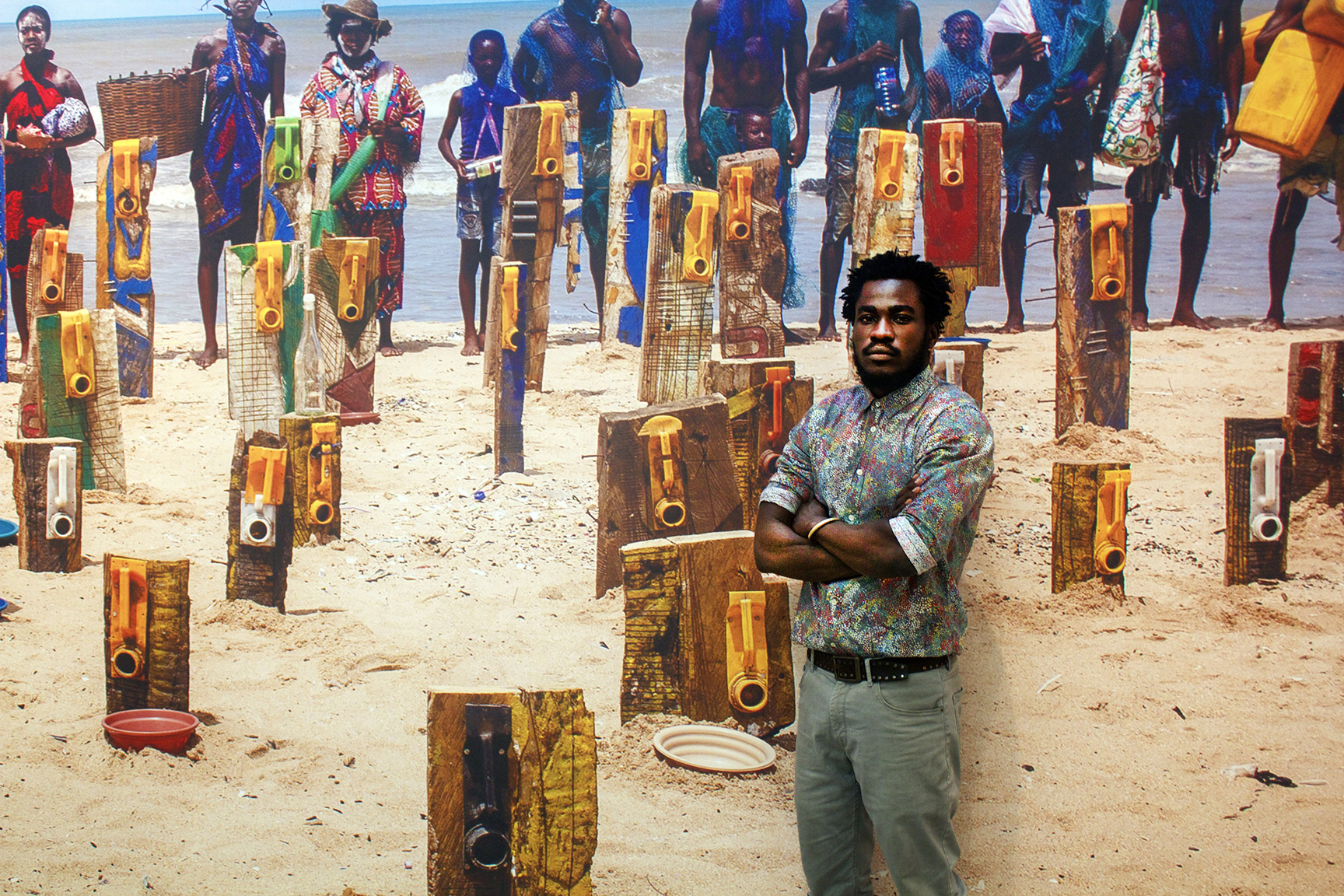

To fill their souls again, they have been working with a group of bead artists located in a township outside of Cape Town, in South Africa, who call themselves the "Haas Sisters." This week at Design Miami, the brothers will be premiering works from this collaboration, entitled Afreaks, which include colorful four legged creatures in varying sizes and large psychedelic mushrooms – more examples of the Haas Brothers, and now Sisters, goal to spread positive vibes. The work will also be on view this February at Cooper Hewitt's Design Triennial.

In the following interview, we talk to the Haas Brothers about their craft, their collaborative relationship, the sexual overtones of their work and how a trip to Africa changed everything.

AUTRE: When did you first start collaborating artistically together? Was there a specific moment when you knew you wanted to make this happen together?

NIKOLAI: My first remembrance of doing stuff together was when we wanted to make these machines. There was a popular artist at the time who made these rolling ball sculptures. We saw that as kids, and we wanted to make this machine in the backyard. We were about 3 or 4.

SIMON: Our very first collaboration started in 2007. He was in a band with Vincent Gallo, and they were touring. I was in school, and they called me and asked me to tour with them. I dropped out and drove to LA to join them.

NIKOLAI: That was our first professional collaboration.

SIMON: Then a friend of ours offered Niki this construction job in 2010, and he asked me to do it with him. We rented a studio downtown. Basically, that’s when we knew that we were going to be working together always. We actually had a conversation about it. We rented that shop, and we didn’t know what to do.

NICKOLAI: In this conversation, we were asking ourselves, “What are we starting a business for?” We just want to work for ourselves and do our own thing. I don’t think we said it explicitly at the time, but we knew we were dedicated just to being happy people. That was the spirit of what was going on. I remember when we sat down and talked about what we were going to achieve, that was the number one thing—being happy, and trying to spread that in our community. Not just the people who we were working with in the studio, but also in the communities outside of the studio, the LA community.

AUTRE: And the rest of the world as well?

NIKI: Yeah, as much as possible. We have a community in Miami now because we go there all the time. We have a community in Europe because we go there all the time. The whole point is to be happy.

AUTRE: When you collaborate on a piece together, where does it start? Is there a brainstorming session?

NIKI: It’s different every time. I think our most explicitly collaborative moments are when we have to sit down and conceive new shows together. On single pieces, we’re collaborating all the time—asking each other questions as we go. Simon’s always working on the philosophy and the deeper meaning behind the work, and he’s always thinking about how the work can change. I’m kind of doing more brutish work, like sculpting or sketching cartoons.

SIMON: He’s the maker, and I’m just testing stuff all the time. I’m a fanatic; I’m a materials person. The way we collaborate is Niki gives life to these processes, and I give him materials to work with. And we always talk about all of it the entire time. Also, as twins, we’re on the same track.

NIKI: It’s not just the conception of the piece. The collaboration doesn’t stop. The African project is such a good example. The actual objects themselves are just a result of the real important part of the project, which is the philosophy of the book. Hopefully people read it. That’s the kind of project that people will put in history books if they read what Simon has written.

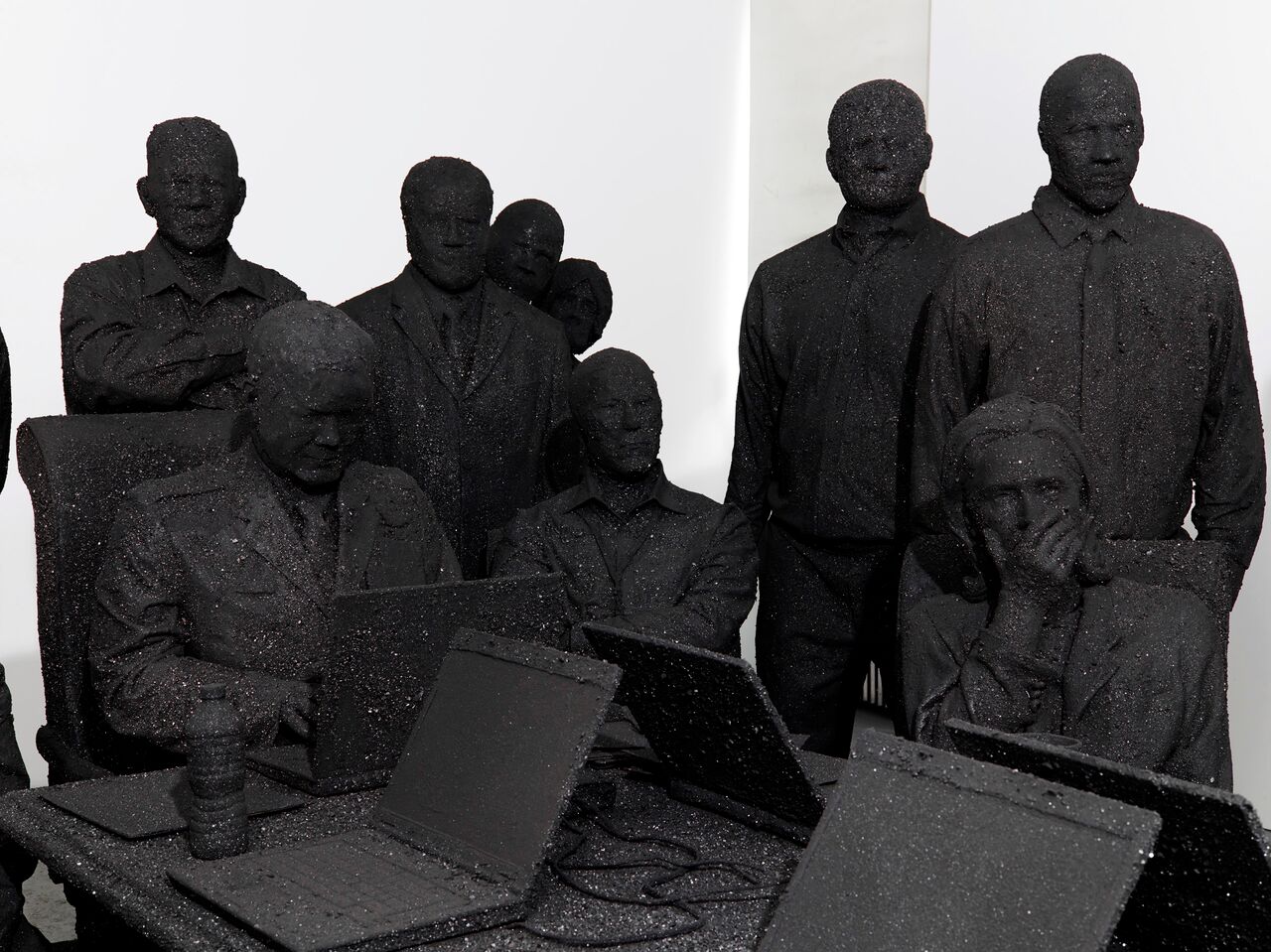

SIMON: It’s basically a feminist, white privilege project that’s wrapped up into something consumable and pretty. That’s the thing—our audience is the 1%. We’re delivering things to them to make them think. It’s not something they would necessarily pick up on the shelf. We get to put this stuff in there to kind of figure out later. We talk about ourselves as entering more into philosophy in that way.

AUTRE: That’s really interesting. My next question was about luxury and the definition of luxury.

NIKI: To be honest, most people who are living luxurious lives have pretty bad situations. There’s something about wealth where it gets to a certain level, and it starts to dehumanize the person. They perceive themselves as an odd commodity, even though they trust themselves more than anyone else. Luxury, honestly, is being as happy as you possibly can be. There’s a sweet spot where you have enough to support what you want to do. At the same time, you are loose enough that you can say, “Fuck this.” If you have to get work, if you have to write contracts—even if you’re making thousands of dollars, it’s not all that luxurious. You’re under your own thumb.

SIMON: Luxury as people understand it is almost like a prison. You go to basically the same hotels and the same restaurants in every country in the world. Someone who is living luxuriously is having the same experience everywhere. You’re getting the Vegas experience all over the world.

NIKI: The Hollywood hotel, the concierge that takes care of everything for you. If we had gone to Cape Town in the luxurious way, we would have been taking crazy advantage of black people. We would have been ignoring the entire context of the point of being there. We would have barred ourselves from doing this project.

AUTRE: Luxury, in a sense, can also mean the freedom to be creative.

NIKI: We have the luxury to do whatever we want. That’s what I’m looking for. The luxury to allow ourselves to be happy. We want to be curious all the time, and we want to explore that curiosity. That’s the luxury we’re after.

AUTRE: You have the capability to work in this small format, and then you can explore all those ideas that were in your head.

NIKI: We talked about supporting our community. We were telling kids that the guy that hired us for this first time said, “Hey, I’m giving you the ability to start expressing yourself.” That’s how we started making our stuff. Later on, our gallery said, “Hey, make whatever you want.” That was a big moment for us. We weren’t making anything cool before that really. Money and space doesn’t make you very happy. I would actually say I was just as happy when I was 18 years old and broke.

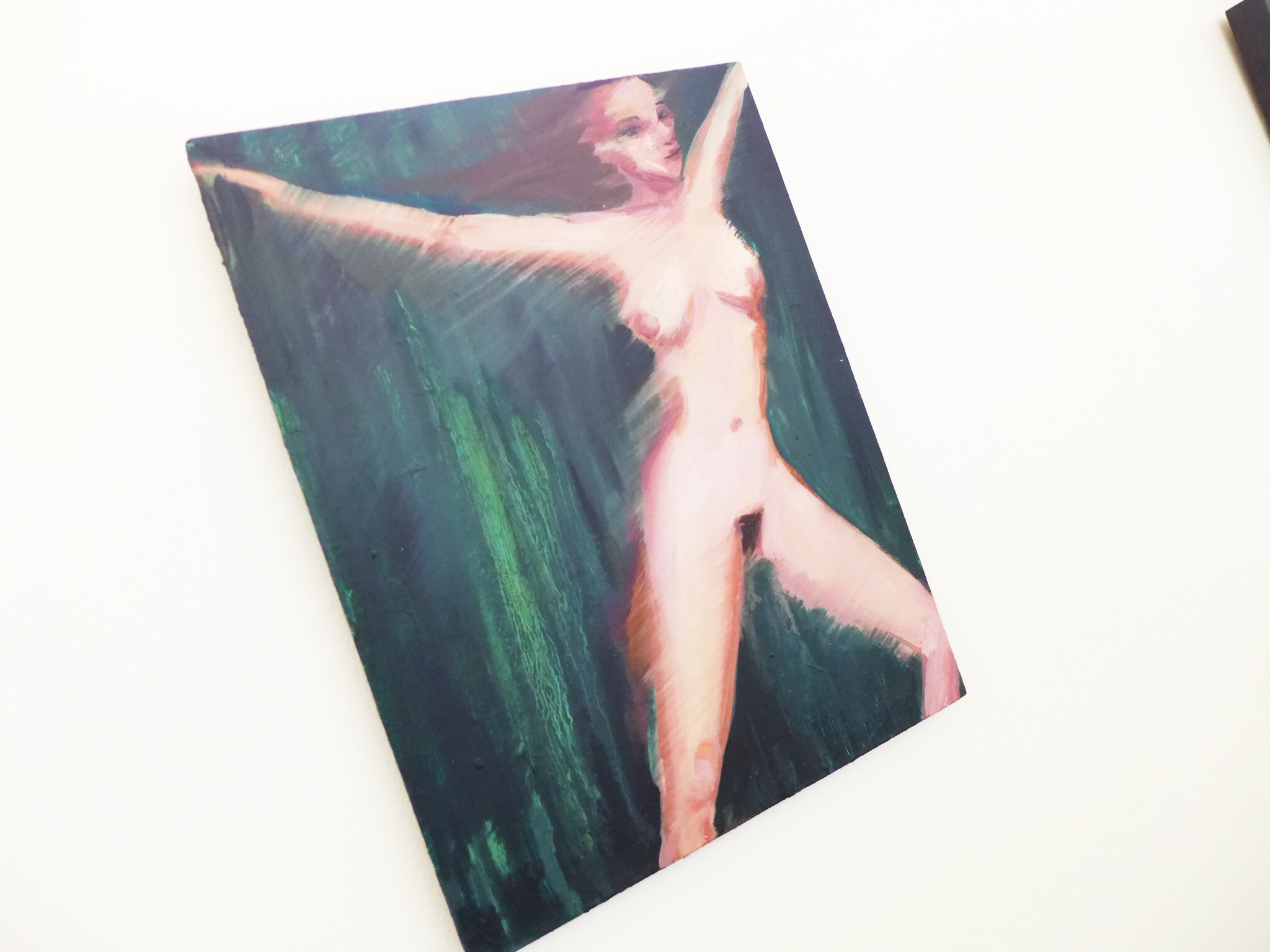

AUTRE: I want to talk about sexuality, because that’s a major part of your work, especially in your drawings.

NIKI: The sexuality, to me, is just the reality of being a person. Everybody thinks about sex. Everybody has sexual organs. It does occur a lot in the sketches in particular. In the rest of our work, it appears about as often as it does in everyday life. You see yourself clothed, and then at the end of the day, you’re naked looking at your own dick. The way that I push sexuality in the cartoons and the way I use it in art work (like the sex room we made a couple of Basels ago), the point is to make it seem like less of a shock. It is simply an innocent expression if it’s done well. Obviously, if not, it can be oppressive. It’s all happiness. It’s an extension of being a person. The point of using it in our work is the idea of leveling the playing field.

SIMON: It’s so positive. Tom of Finland was more centered on the erotic. The idea behind this is positivity. There’s a very positive message. Beyond that, we focus a lot on animals too. Animals and sex are really common themes throughout history, design, and art (which were the same things until recently). We feel like it’s a natural interest. It’s what’s around us. To exclude it from the work is almost weirder. I was in drawing classes at RISD, and there would be people doing life drawing classes who would leave out the penis. That creeps me out. Showing it is not creepy. Taking it out, showing me your thought process, is kind of creepy.

AUTRE: There’s so much shame attached to sexuality in our culture.

NIKI: We are vehemently anti-shame. That’s one of the pillars that Simon set up for our ethos very early on. Any time we sit down to do a piece of work or a show, we make sure to follow these guidelines we made for our studio.

SIMON: The first few sexual pieces, people would come up to us and say, “Oh my god, you can’t show that.” That’s shaming. We’re not going to listen to them. It’s because of their own discomfort. We made a piece for Basel about sex and shame. People would enter through this giant vagina. We like to get people to consider their own thought processes as they’re experiencing these things. I think it’s important.

AUTRE: It is important. There is a lot of censorship going on these days, like with Instagram.

SIMON: The fact that you can’t show nipples on Instagram pisses me off. The nipple can’t be free; that’s so stupid.

NIKI: We’re not trying to be shocking when we talk about sexuality. People think we’re sensationalist and shocking, but really we’re just expressing what we think.

AUTRE: Do you ever have creative disagreements? How do you resolve them?

SIMON: We have, though it’s kind of rare. We had a big fight in Cape Town, but that wasn’t creative.

NIKI: Talking to each other creatively, we take each other seriously. If Simon doesn’t like something I’m coming up with, or if I don’t like something he’s coming up with, we just try to explore it with each other. You probably have a point, let’s find what it is. Our creative fluidity is beyond good.

SIMON: In school, I had critiques by some teachers who had chips on their shoulders. It was so obvious. They will give shaming critiques of work. We don’t do that to each other. It stunts your creative growth so much. We understand that if one of us shits on the other one’s piece, he’ll stop exploring it and be afraid to do it. I know that his output is going to be incredible, so I have to trust it, and vice versa. The biggest fight we had was in Cape Town, and it came only because we were both going through so much. We’d been riding this crazy high from getting pretty successful pretty fast, and it kind of hit us. When we were in Cape Town and working with these women who had so little, it was like, “What am I doing?” Both of us were going through internal turmoil, which caused us to have a big fight.

NIKI: There were also a bunch of reasons why we had to flesh things out. After the fight, it ended up so much better. It was so worth it. That was the first time we ever had a fight. It’s crazy. Literally, if you talk about the moment before we went to Africa, we had our first solo show in New York. It was met with tremendous success; we sold everything.

AUTRE: Was that R & Company?

NIKI: Yeah. We were hanging out with collectors and all that bullshit. We were staying at a friend’s penthouse. We were taking ecstasy and listening to soul music, and it was so fun. I don’t feel bad for doing it at all; it was unbelievable. But then we go from this moment of complete pleasure and excess to being dumped in Kairicha. We set that up for ourselves, but it was a good reality check. Fuck. Who gives a shit about what we just did? I was proud that we did that, we worked really fucking hard. But we’re young white men. We grew up knowing A-list celebrities. Half of this, whether we like it or not, was handed to us. Suddenly we're working with black women in Kairicha where black people still don’t have the same rights, they are not being given any chances. When we came into the picture, we did a small fair in South Africa, it was the first time they had ever been to the town’s center. That was the first time they got to go to a fancy event.

SIMON: And the crowd that came in was shocked that they were all in there, and as the artists especially. It was really cool.

NIKI: People say it’s not racist in South Africa, but then you try to take them all out to a sushi restaurant, and you can’t do it.

AUTRE: It seems embedded.

SIMON: They’re like, how about going to KFC and going to the top of the hill instead? We actually wound up doing that, and there were people taking photos of us. It was so bizarre.

NIKI: You have to realize, though, that that’s how these people grew up. That’s what it’s like in South Africa, white or black. The whole black community has its own issues with intolerance too. They’re super intolerant with gay people. It’s all fucked up. What we have to understand is that everyone growing up there has grown up with a certain social structure. The idea of ignorance really comes into play. Culturally, people were brought up in an ignorant way. We want people to understand that you don’t want to isolate people you’re hoping to change. If you do that, nothing’s going to happen. And everybody, as evil as they may seem (and I don’t even believe in the idea of evil), nobody is actually evil. Everyone is a person deep down inside. Whatever it is that they’re reacting to, if they’re acting in a way that’s full of shit, like demeaning a person because of their skin color—I believe that they are fully capable of dropping that. It takes time. I think that the Internet is the biggest purge of that of all time. All of a sudden, nobody on the Internet community seems tolerant of homophobia or racism. As a mirror of society, you see society not willing to tolerate that anymore. The Internet touches about 80% of their lives. That’s great. They all have cell phones and listen to Beyoncé and One Direction. But the thing is, Beyoncé is not homophobic or racist. When you have idols that are being put in front of people like that, it’s only a matter of time before it melts away. In fact, anybody who is younger than us is not an issue. You just have to wait for the old people to die away. Although, I’m sure there are some people carrying the torch who are younger.

AUTRE: A lot of people don’t get that reality check. They go to the developing world, but there’s no reality check.

SIMON: You turn into a monster. I felt myself turning into a sharky monster before we went to Cape Town. I was noticing changes in my behavior. Like, I was totally okay with being an asshole to somebody. That’s not like me, and it started to bother me a lot. Thank god we went to Cape Town; it hit us so hard. I remember, right after Cape Town, we went to Miami. We wound up in a G7 flying back here, and I could not enjoy myself. It felt brutal.

NIKI: These pieces of art are selling for thousands of dollars. At some point, it’s too much money. Nothing is worth that much. I know some of our stuff is stupid expensive. But the point is that it’s feeding something much bigger. We’re trying to bring it back to the community.

AUTRE: With you guys, there’s craftsmanship.

SIMON: There are definitely reasons why our stuff is expensive.

NIKI: If there’s an art piece that has historical value, but all that’s happening with it is the piece being taken and used as a commodity. It’s dehumanizing. It’s been moved around in the market with a shitload of money on it. No one needs something that costs that much.

AUTRE: How did the project in Africa come about?

SIMON: Cape Town was named world design capital, and we went for a fair to show some of our pieces. When we got there, we were being tourists looking for art in South Africa, where everything is totally whitewashed. We went to this craft fair, and there was this booth with really cool beaded animals. The woman in the booth was so fascinating and cool and making these beautiful pieces. We just loved her and her story. The booth is called Monkey Biz. On each piece, they have a tag with the name of the woman who made it. We thought that was amazing, because that doesn’t happen very often. It’s a small thing, but it’s actually a really big thing. That’s what got us to want to start doing it. We had this whole penpal exchange with this woman—Montepelo—and her team for about a year, and she really wanted us to come. We showed up and started working with them. They were all afraid of working with us, actually. They’re used to being treated poorly. As soon as they realized we weren’t on that track, it became this really awesome community building experience.

AUTRE: When will those pieces be shown?

SIMON: In December. December 4th.

AUTRE: So that’s your next major project?

NIKI: Yes. And we have another show in February.

SIMON: The theme is beauty.

NIKI: We’re trying to transgress beauty. We’re trying to get rid of our exclusive authorship.

SIMON: Jeff Koons would never name all the fabricators that worked on his project. That’s what we’re trying to transgress. I think it’s kind of cool.

AUTRE: Design and fine art—where is that line?

SIMON: The line is the people who are going to make money off of it. It’s completely commercial. Also, the word “design” is completely Western and very modern. There was never a distinction between the two until recently in our culture. It’s so location and time based that we find it to be gross. We don’t really make that distinction.

NIKI: At the same time, we’re proud to be a part of what’s considered the design community. The truth is, we’re just doing what we do. No labels, man.

SIMON: We rose up through the design world, but we are contentious there. As our stuff is being thought of more as art, the design fair has tried to push us out. Art Basel and Design Miami are the same thing, but they don’t know what side our work should be on.

NIKI: Design Miami has been trying to push us out because we’re “art.”

SIMON: That actually happened with this Cape Town project. We had to appeal and fight for the right to get into it. They told our gallery that they couldn’t show it unless they had us in that booth.

NIKI: The design line exists only in the eyes of the people of commerce.

AUTRE: What do you think will change things?

NIKI: It’s already happening. The Internet, again, is leveling everything. Hashtags have become more important than library cardstock. The way that people think about design now is like library cardstock. The hashtag is going to take over. People in our generation don’t give a shit. People who are old have dedicated time to a certain way of life, and they’re really resistant to changing that way of life. But the truth is, they’re old, and they don’t know what the fuck they’re talking about.

SIMON: The reason why it hasn’t already changed is literally money, government, etc. But that will go away, and it will all be much chiller. It’s clear from looking at the Internet what’s going to happen. Growing up gay in Texas, I saw very few people who were out in the public eye. The best I could get was Queer Eye for the Straight Guy on TV. Now, on the Internet, you can see whatever you want. Everything is going to change.

You can see the Haas Brothers' "Afreaks" this week at the R & Company booth at Design Miami opening on December 2nd. You will also be able to see the work at Cooper Hewitt's Design Triennial, which will open on February 12, 2016 and will run until August 21, 2016. Purchase the "Afreaks" book here. text and interview by Oliver Maxwell Kupper and Summer Bowie. photographs by Sara Clarken