Leo: Which is kind of funny because, in a way, your work has this funny dialectic where there’s an act of withholding and then the histories that you're drawing from hinge on revelation or disclosure. These secret operations or conspiracy theories you draw upon, despite gesturing towards the unknown, almost require the act of disclosure. I mean, if Project Stargate was never disclosed, its relationship to the vast corpus of state secrets and the unknown would obviously be invisible. In a sense, without disclosure, conspiracy theories and the like would be, well, nothing.

Nina: I think the way the work functions is constantly changing, as well as my desires and intentions. There will always be contradictions because the world is contradictory in nature. There’s a logic involved in the work’s creation, but there’s also a sort of non-logic that exists. I think this also speaks to my interest in mysticism and spirituality. It’s an exploration of the way that belief exists through a subjective logic, where rules can be broken at any time. People sometimes ask me if the work is a case study or something, maybe because I'm interested in critical theory, and cite inspiration from post-structuralist and sociology texts, but this work is not meant to be anthropological. It's partially about my own experience researching in these spaces. The way my own mental health fluctuates through the process is layered in the work.

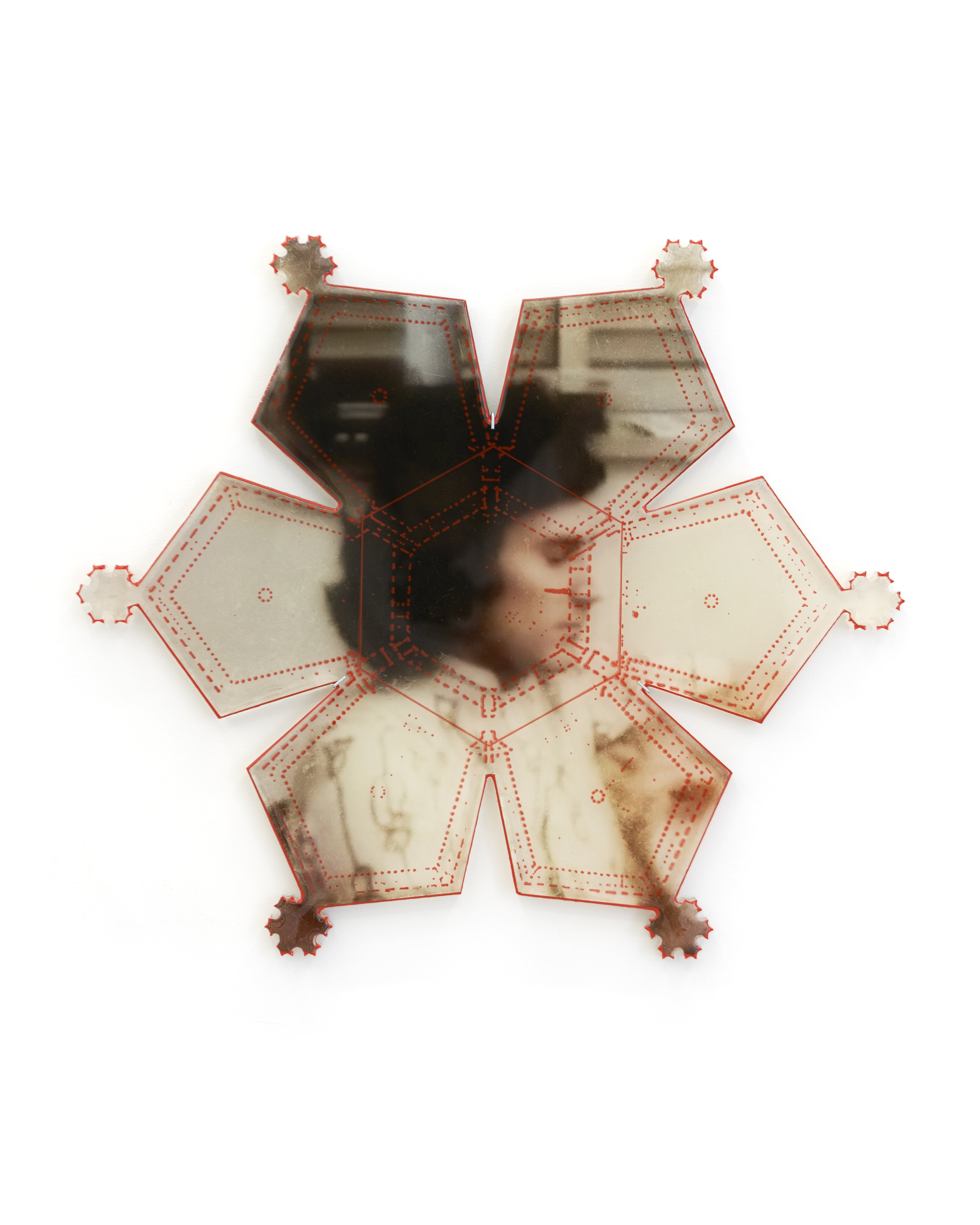

Leo: You’ve talked about the relationship between the citational or re-appropriated imagery used in your practice and its relationship to your music background. What about some of the current techniques you use? Namely, the suspension of imagery in encaustic or resin and the recurring motif of marking your works with shapes evocative of divine geometry.

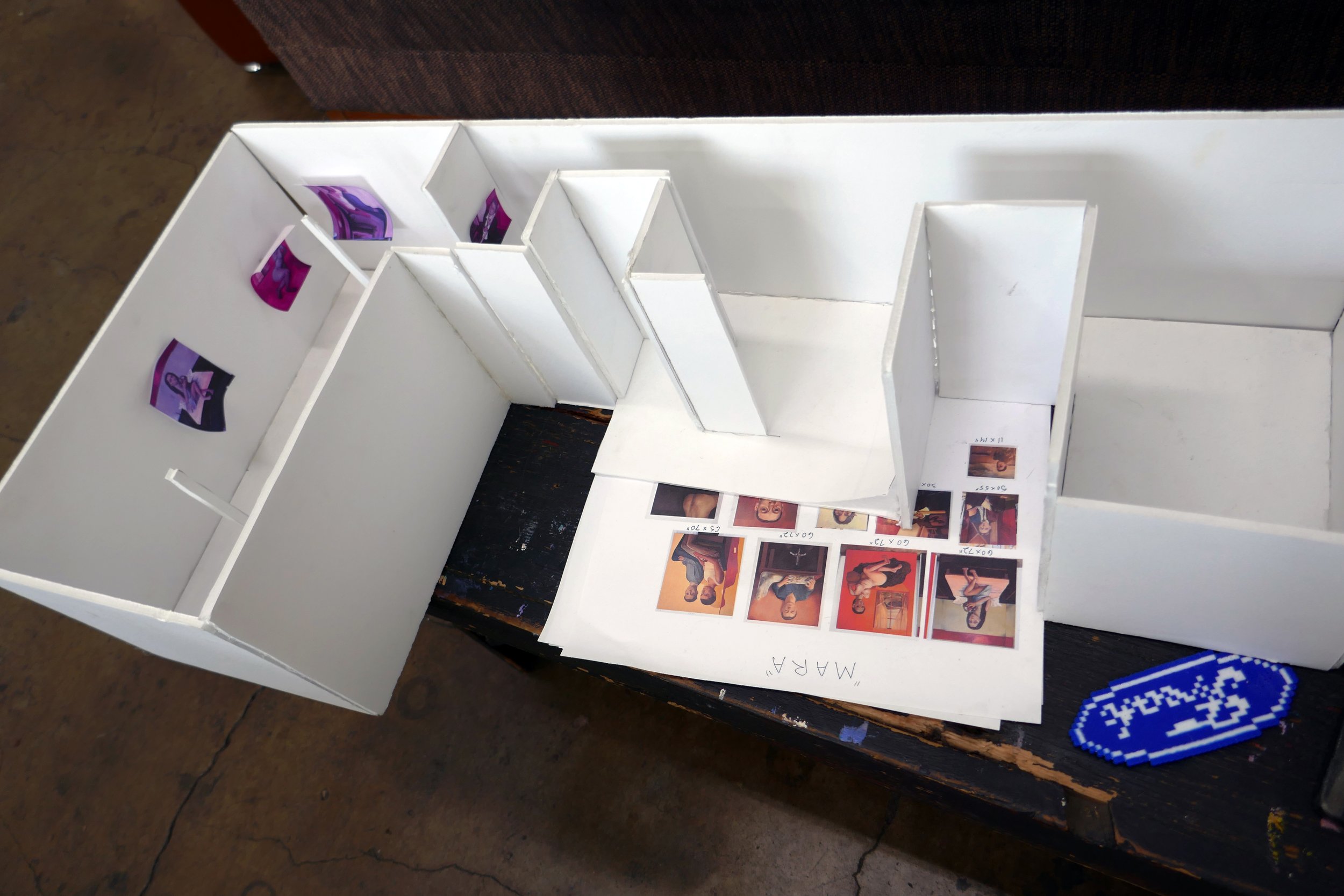

Nina: The resin pieces were largely inspired by DIY plaques or memorials on the walls of dive bars. I grew up in Miami and going to bars is a big part of the culture there. There’s this restaurant called Flanigan’s that is covered wall-to-wall with photos of people proudly holding their caught fish, and there’s this one photo of a “square grouper”, which is slang for a big brick of discarded marijuana found floating in the ocean. I think about that photo a lot [laughs]. When people cut out newspaper articles about bar regulars or employees and seal them into a cut-out piece of wood with table-top resin—I really like these moments of forging personal histories and creating objects to commemorate events that aren’t usually given space, but are important to that particular place. I became interested in how the characteristics of those forms give them importance, their shape or composition, which evoke other monument-like objects. Also the gesture of encapsulating and preserving something in resin, and how the desire to protect it against weathering gives it a quality of recorded history.

I’m drawn to materials with an alchemical quality to them. Materials like encaustic and resin that activate the work like a potion. The heat, the mixing, the chemical interaction—it all ties into my interests of esoteric knowledge and alchemy as well.

Leo: Could you also talk a little bit about how and where you source your imagery?

Nina: I gathered a lot of these images from leaflets, pamphlets, and press packets that different sectors of the US military and government released as gestures of transparency, usually as a response to controversial events. One of the main ones I sourced from was a book that the Air Force released that basically tried to disprove the 1940’s UFO sightings in Roswell. The book contains a collection of photographs documenting tests that involved throwing human sized dummies out of planes to test balloon technology, thereby offering an explanation for the alleged sightings. The way in which these booklets attempt to control and orchestrate the narrative really struck me, especially how they rely on the photograph as indisputable proof. I was also working with these Department of Energy Packets that were released in response to the environmental and health damage caused by nuclear testing done during the Manhattan Project. It’s funny, it feels so topical because of Oppenheimer.

Leo: In the new series of work being shown at Silke Lindner, there's a fairly generic image of a lamb in one of your works. Correct me if I’m wrong—I’m guessing this image isn’t from a secret government operation. So, how do you choose your imagery?, because there seems to be a mix of images directly relating to the histories engaged by any given number of your works as well as seemingly unrelated images.

Nina: That's a really good question. I'm interested in the juxtaposition of various source materials and how they interact with each other in their recontextualization. For instance, having images from an official CIA archive existing on the same wall as images from a more subterranean source, like page 57 of a conspiracy theory message board about the pope’s ties to the satanic church. The scrambling breaks down the hierarchies of information, giving it a new rhizomatic manifestation. I want to deconstruct the ways we assign legitimacy to content based on its characteristics and the context, or lack thereof, that it's delivered in. The lack of context breaks the image down into a more symbolic function.

Leo: Your work also possesses a flickering quality, which I think has to do with an engagement with temporality. For example, in the 20th century Air Force book you just talked about, photography was used as a way of assigning objectivity or truth to a given event. But now, it's come full circle: no imagery is trusted in our post-truth era. This isn’t only due to the advancement of photo editing software, but also AI capabilities. It’s almost as if the possibility of the camera or image being objective has entirely gone out the window.

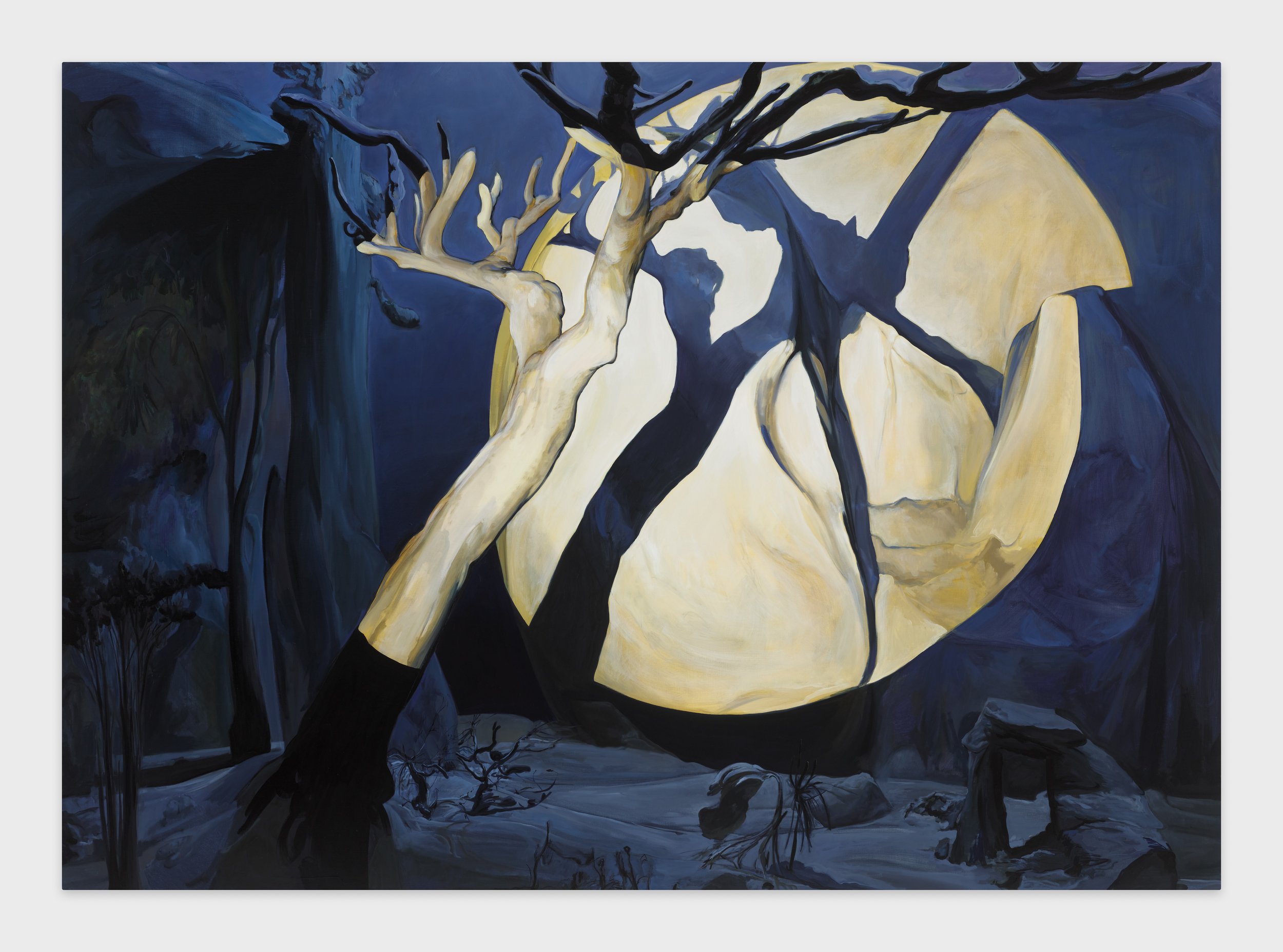

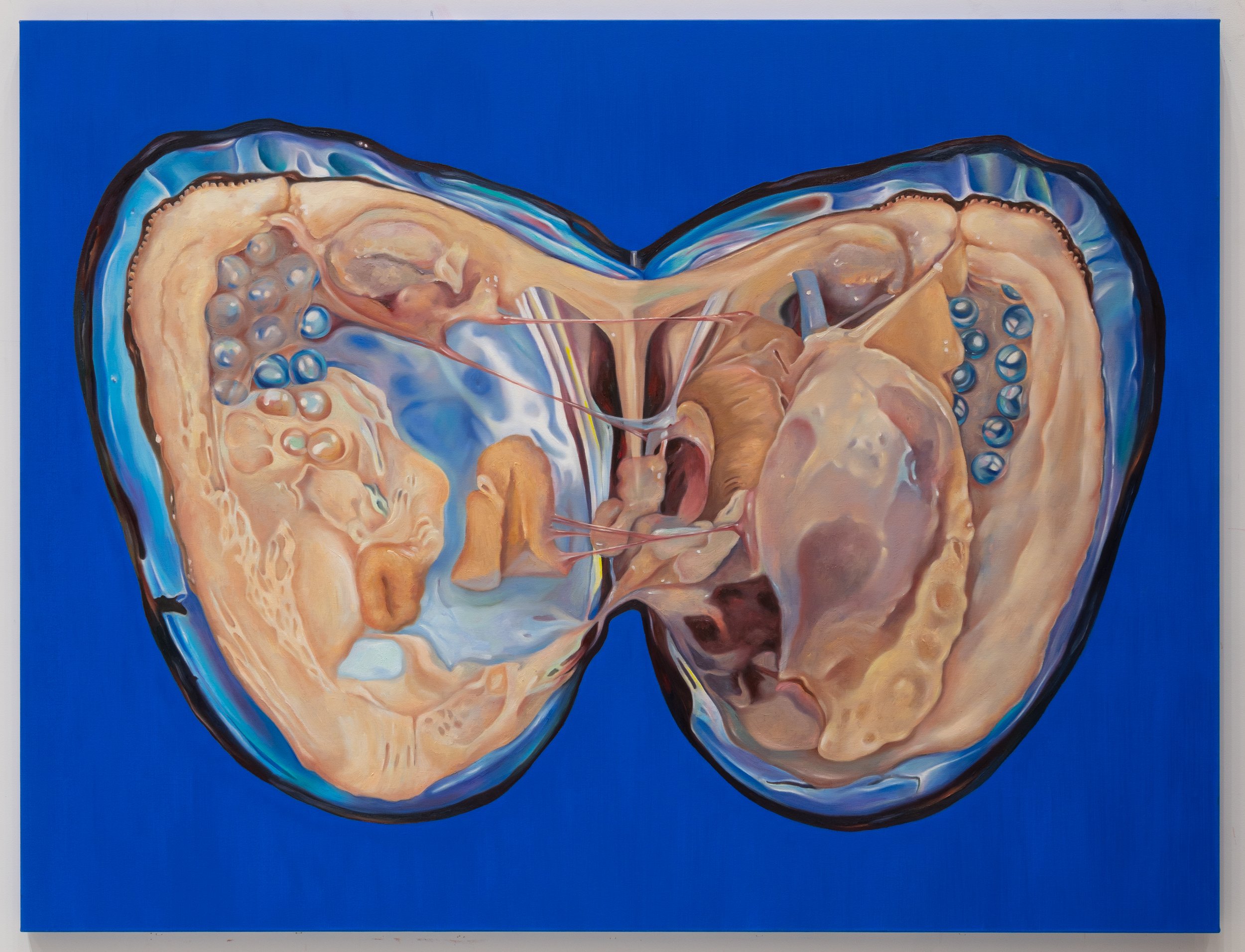

Nina: Photography’s function as evidence or data feels so topical right now with all that’s happening with the advancement of artificial intelligence. A big conceptual inspiration for the show was the idea of the operational image, which Harun Farocki talks about in Phantom Images. Basically, it’s an image that exists for a function, like a still from a drone camera containing GPS coordinates and a crosshair, or a sonogram image. The concept sparked a line of inquiry for me about images that hold authority through their technological characteristics and qualities. Operational images contain some sort of objective truth value because of their function of measurement and task. I tried to employ some of the compositional characteristics commonly recognized in these images to make paintings.

Leo: These images are legitimized not through their ability to reproduce a view of the world as it's seen by the human eye, but through their ability to penetrate this form of vision, which is then further legitimized by their role within a larger operation of knowledge accruement. I think this is formally mirrored in your work in the way your sculptures are reminiscent of cosmograms, of charts and diagrams that show the world as it is beyond the pale of the mundane. Your practice seems to almost fall into the category of a research-based practice—just without the designer-furniture-and-text installation format.

Nina: Yeah, you know one of my professors said to me during a crit that my work is trying to do what Hans Haacke does but in the opposite way, and I kind of loved that.

Leo: I think it's a huge compliment to be honest. It’s a conversation I’ve had with several people but the problem with a lot of these practices (not Haacke’s, obviously) is that I’m not about to spend sixteen hours reading in a gallery.

Nina: I have this vast archive of documents and images, but I always try to find a way to synthesize them into more digestible forms and engage the senses in an exciting way, because at the end of the day we live in a super fast-paced world with a short attention span, and I also want that to be part of the work. Kind of mimicking the ways images become iconographic in social media, which we’ve all gotten used to. As I mentioned, allure or seduction through material is a part of the work. People always come up to me and are like, “I want to lick the resin”.

Leo: So why the recurring turn to specifically military-centric special operations and conspiracy theories?

Nina: My dad's father and his three brothers were all in the US Army or Navy during World War II. My grandfather was a Pearl Harbor survivor and a decorated Navy captain. On the contrary, my father was successful in dodging the Vietnam draft multiple times. They tried to draft him, I think, three times. He learned this yoga technique from his friend which involved clenching his sphincter muscle for extended periods of time to heighten his blood pressure. His blood pressure was so high every time he would go in for his draft physical the doctors were like, this makes no sense, you’re in perfect health but your blood pressure is through the roof. Once, they sent him to the hospital to be monitored for 72 hours because they assumed he was on drugs. But it worked every time! Anyways I can’t find any information about this technique on the internet, but I love the story. Maybe these two facts can speak to some of the poetics of my inclination.

Leo: [laughs] I think this family history of where yogic practice and warfare meet feels appropriate for contextualizing your work. Can you talk a little bit more about the role of psychology in your practice? We’ve talked about how Carl Jung’s ideas have been influential for you and even in this conversation you’ve mentioned fear, anxiety, and paranoia.

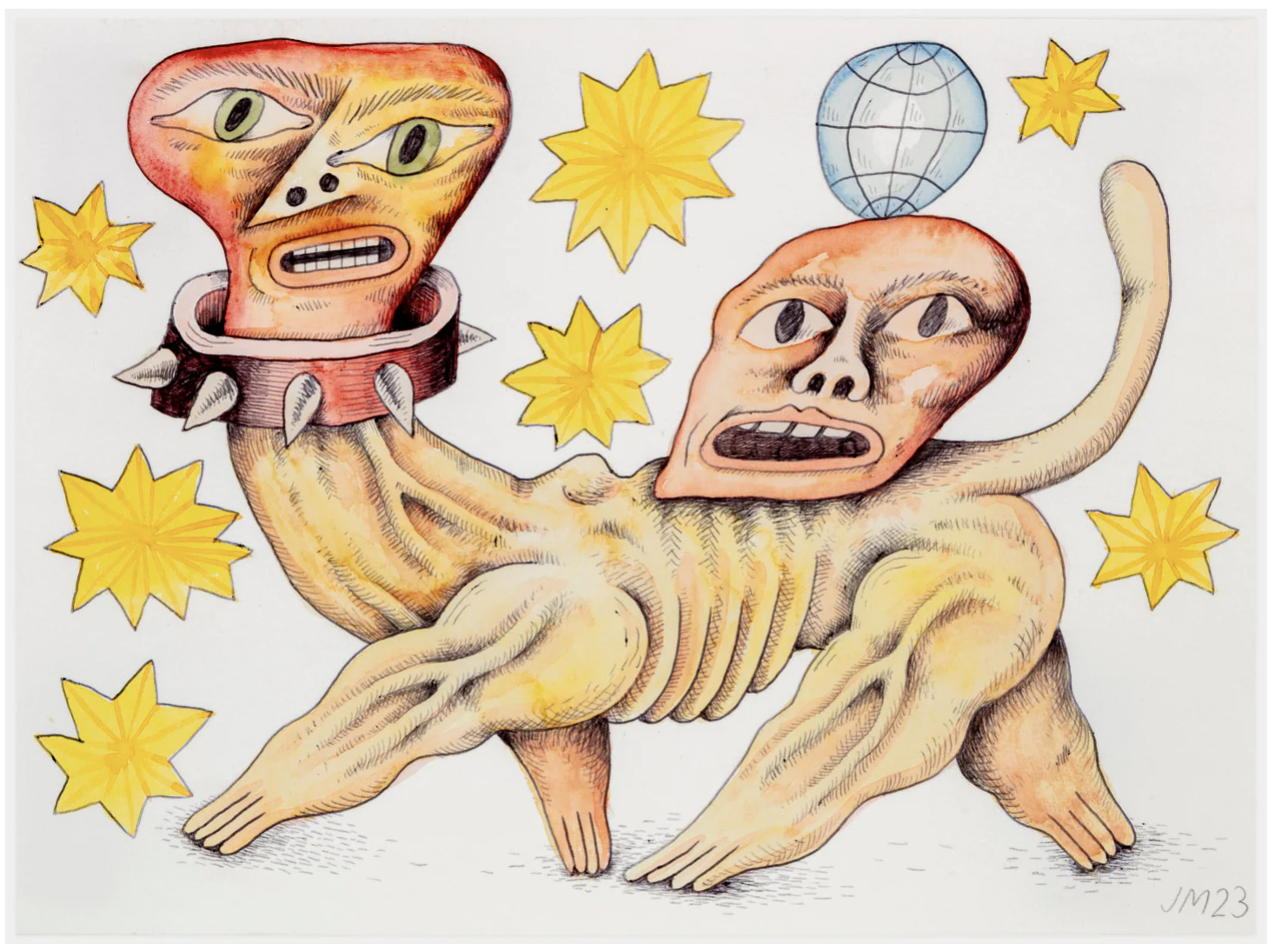

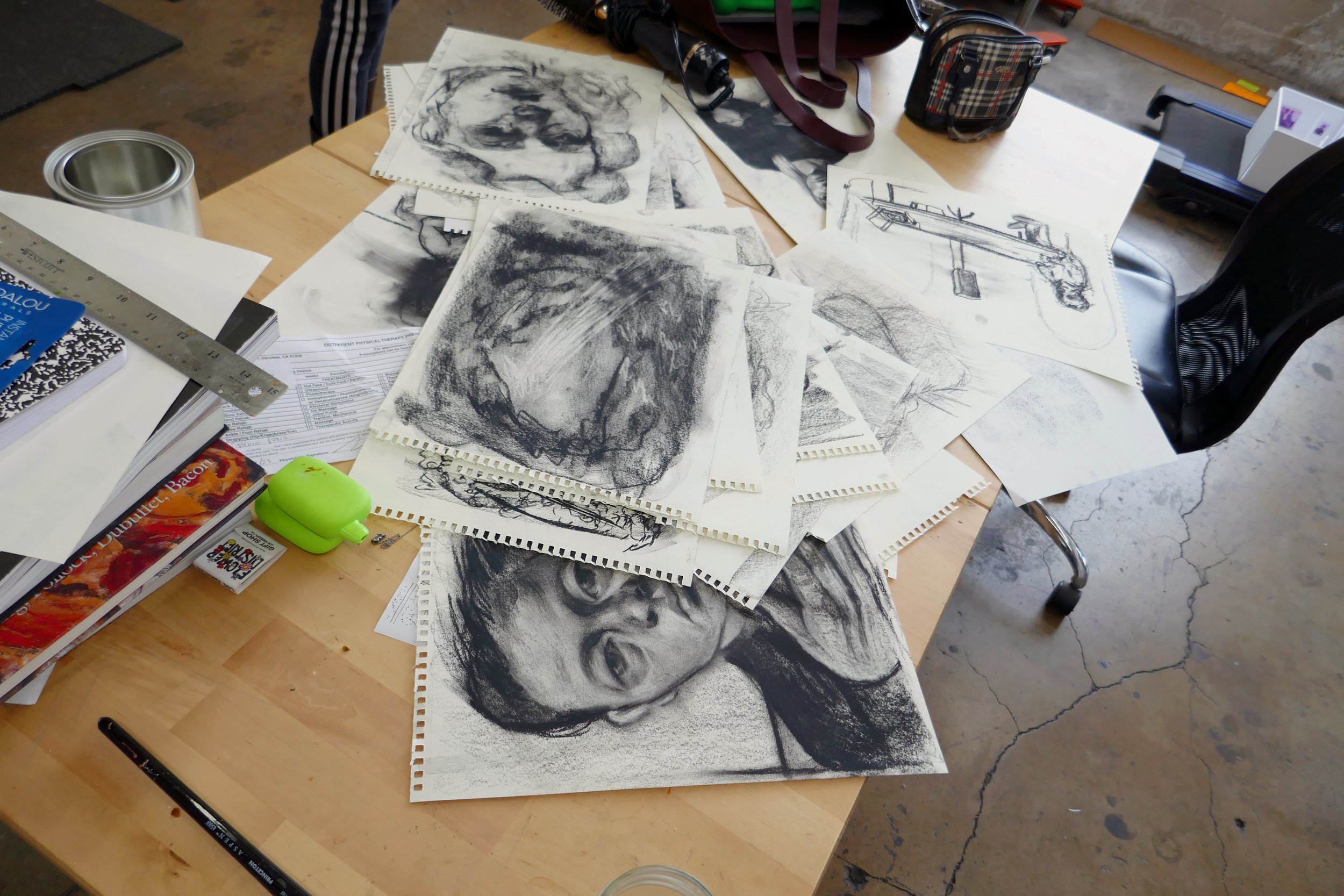

Nina: I’ve mentioned this to you before, but I have my own issues with mild paranoia in my personal life. Or maybe it isn't really paranoia, just a result of all the things I've experienced. I suffer from OCD and it feeds a lot of my compulsions to collect and organize, but I don't view the main mode of the work as being biographic or anything. I mentioned before that I do try to pick up on universal frequencies through letting go of control and creating methods or constraints for the collection process. Sometimes I rely on algorithms to reveal the next subject, like a form of divination. For this new work, I tried to treat my brain like a processor of information in order to create some of the shapes. On some days, I would take in curated information for several hours, and then have a drawing and collage session afterwards. For instance, I might look at early alchemical diagrams, a collection of fractal geometries, and early panopticon architecture to an exhaustive point, and then try to create something while in a disassociate state after I’ve subconsciously absorbed the content. It’s somewhat like a form of automatic drawing. It’s a way of letting go, as well as attempting to tap into the power of the subconscious.

Leo: Is this a consistent way of working in your practice or is this something you developed or turned towards in your new show with Silke Lindner?

Nina: In some ways, it just became more fine-tuned and intentional recently.

Leo: I think your interest in both diagrams and psychology makes a lot of sense. I’m thinking now of Lacan’s graph of desire, and the attempt to visualize in the simplest form a titanic, ungraspable force in the world. In the context of psychoanalysis, clinical case studies—with their lived human experiences and specificities—are really the only way of thinking about such overwhelming forces, like desire. You can’t picture desire as a whole but you can think of it through small points of visibility, like with the subject talking through a traumatic event at the clinic. I think your images and work operate in much of the same way.

Nina: Yeah, it’s like trying to grasp and organize little moments within an infinite network that feels impossible to see or understand as a whole, but there are instances of understanding found in these little moments of revelation. At the end of the day, it’s an exercise in reality manipulation.

Soft Power will be on view at Silke Lindner until October 7th.