Interview By Agathe Pinard

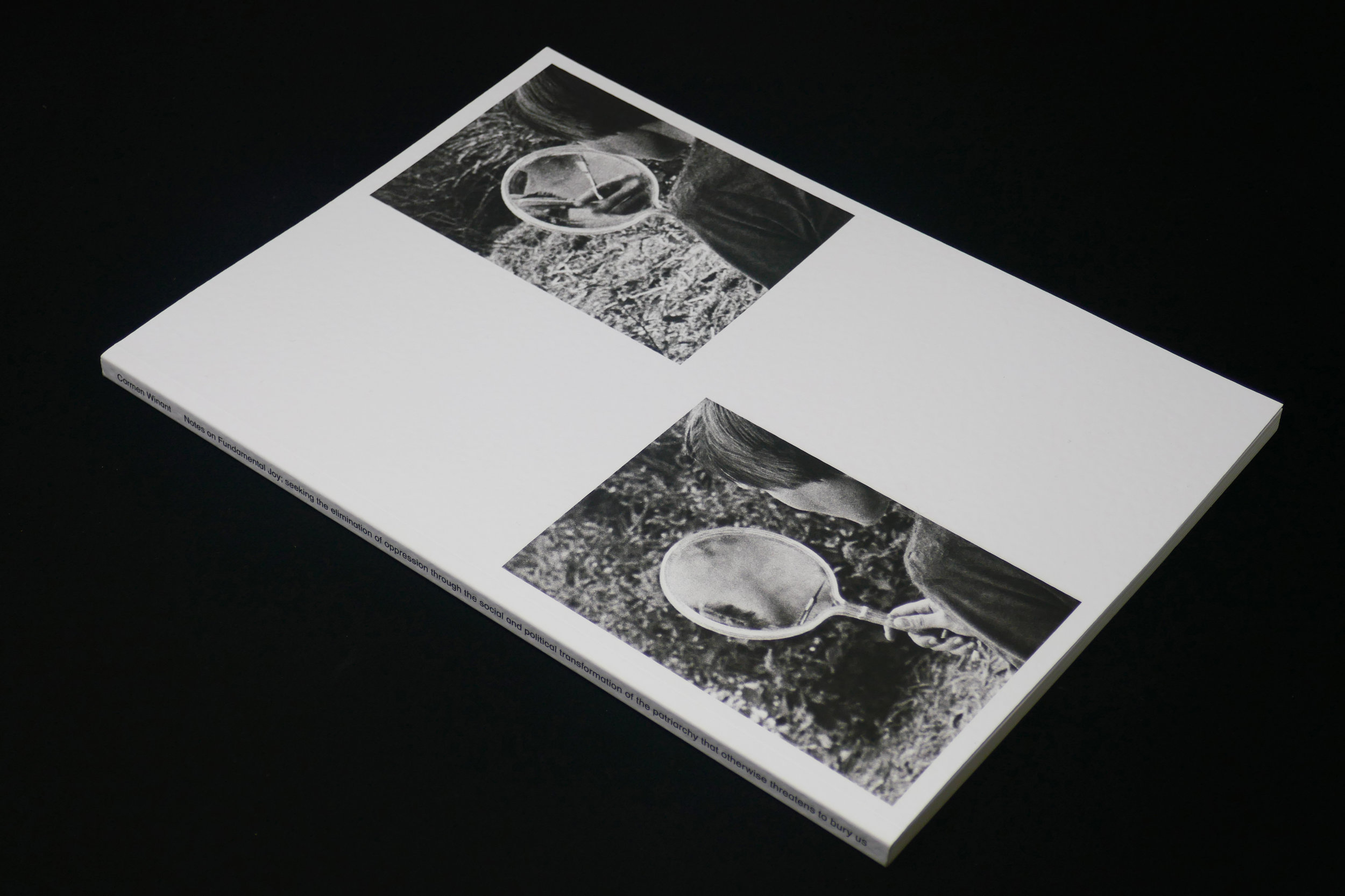

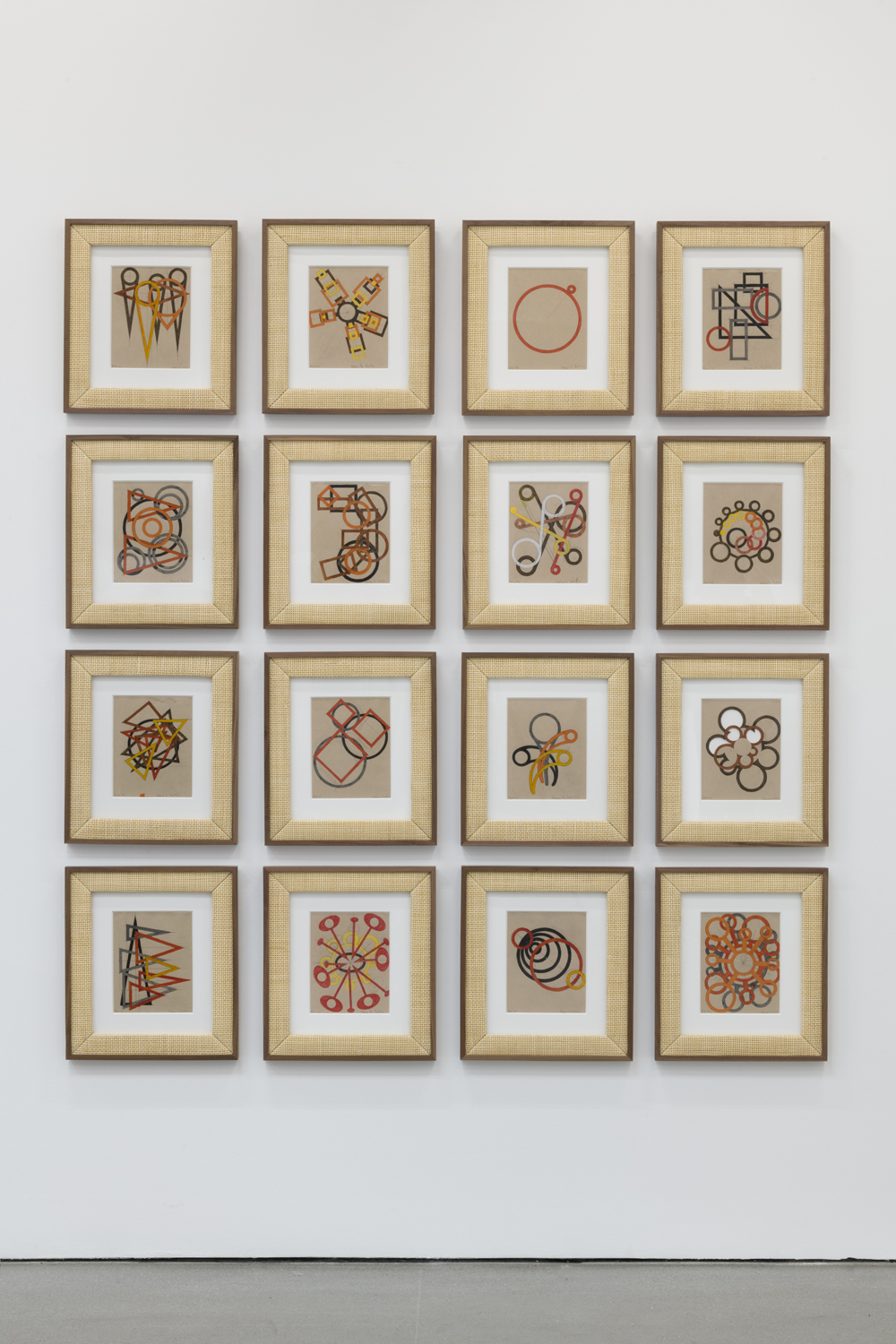

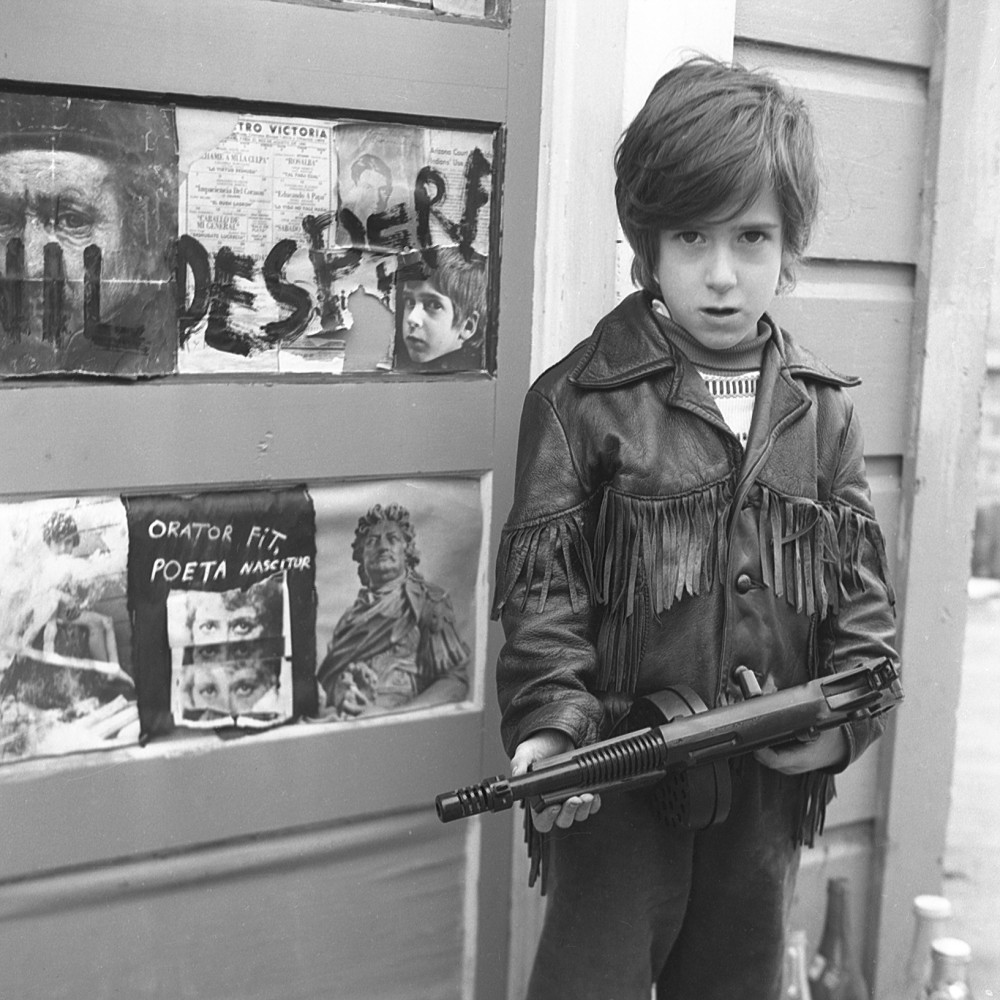

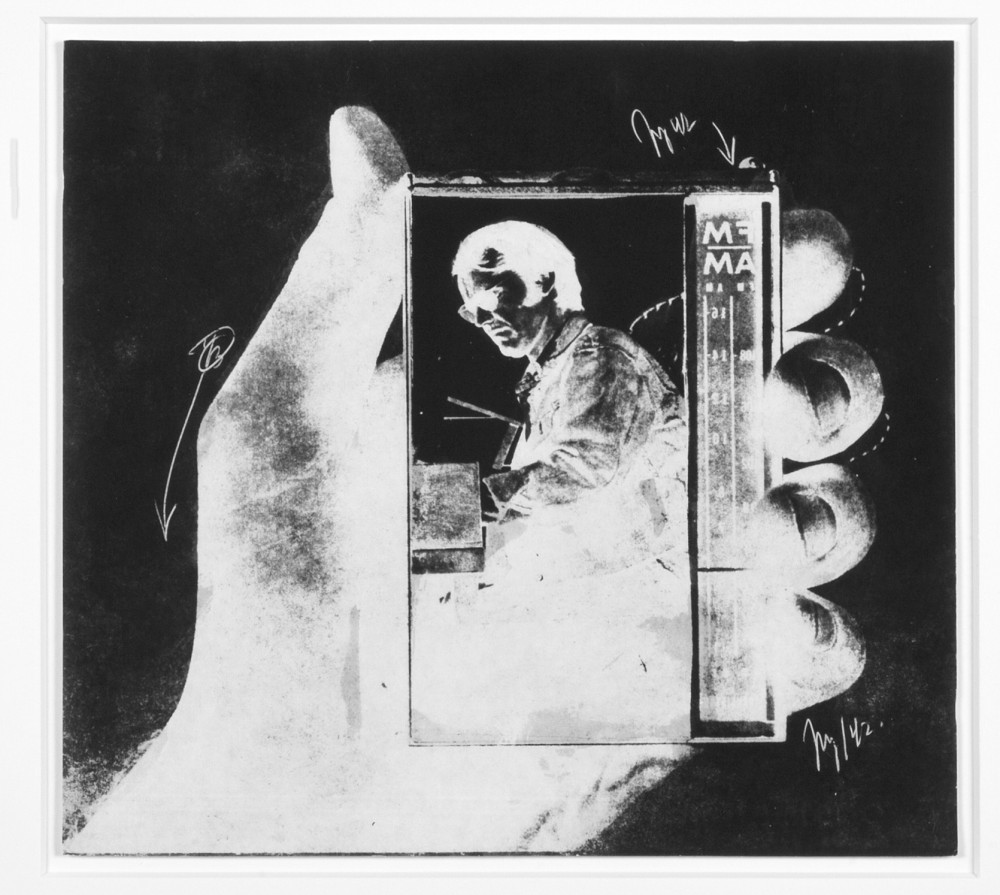

Photographs By Jeff Mclane Courtesy Of Tanya Bonakdar Gallery

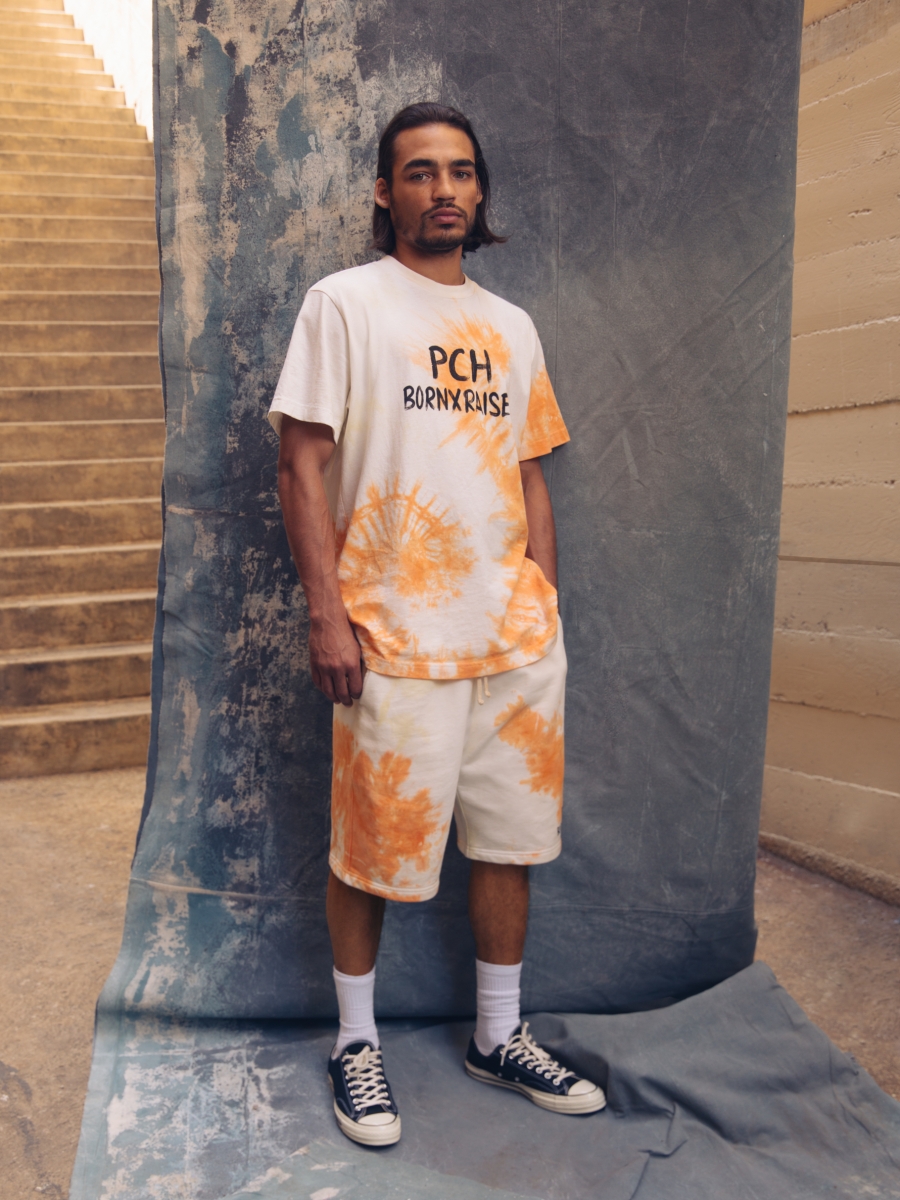

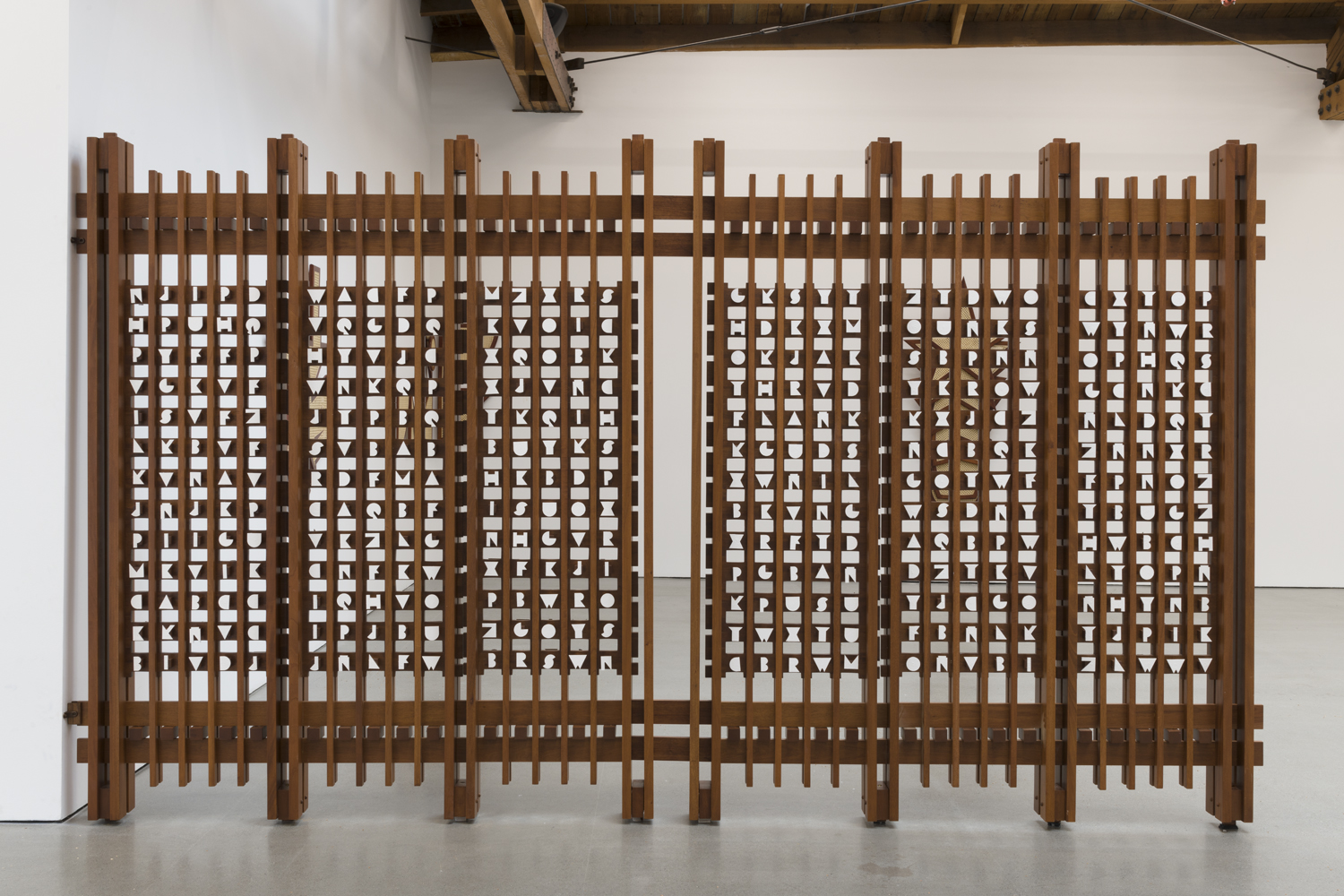

Vocalist, guitarist and interdisciplinary artist Jónsi has entertained a fascination for sound for most of his life, his more well-known output being the Icelandic, experimental band Sigur Rós. The indelible contribution that this band has had on the world of contemporary music is undeniable. The release of their 1999’s album Ágætis byrjun changed the landscape and the very definition of ambient music. Jonsi’s intentions have remained the same since his first experiments with sounds; “changing the way people think about music.” For his first exhibition at Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, Jónsi plays on multiple senses with a series of immersive installations where visitors can individually experience smell, hearing and sight in a public setting. I had the chance to ask Jónsi a few questions about his show and his personal relationship to sound.

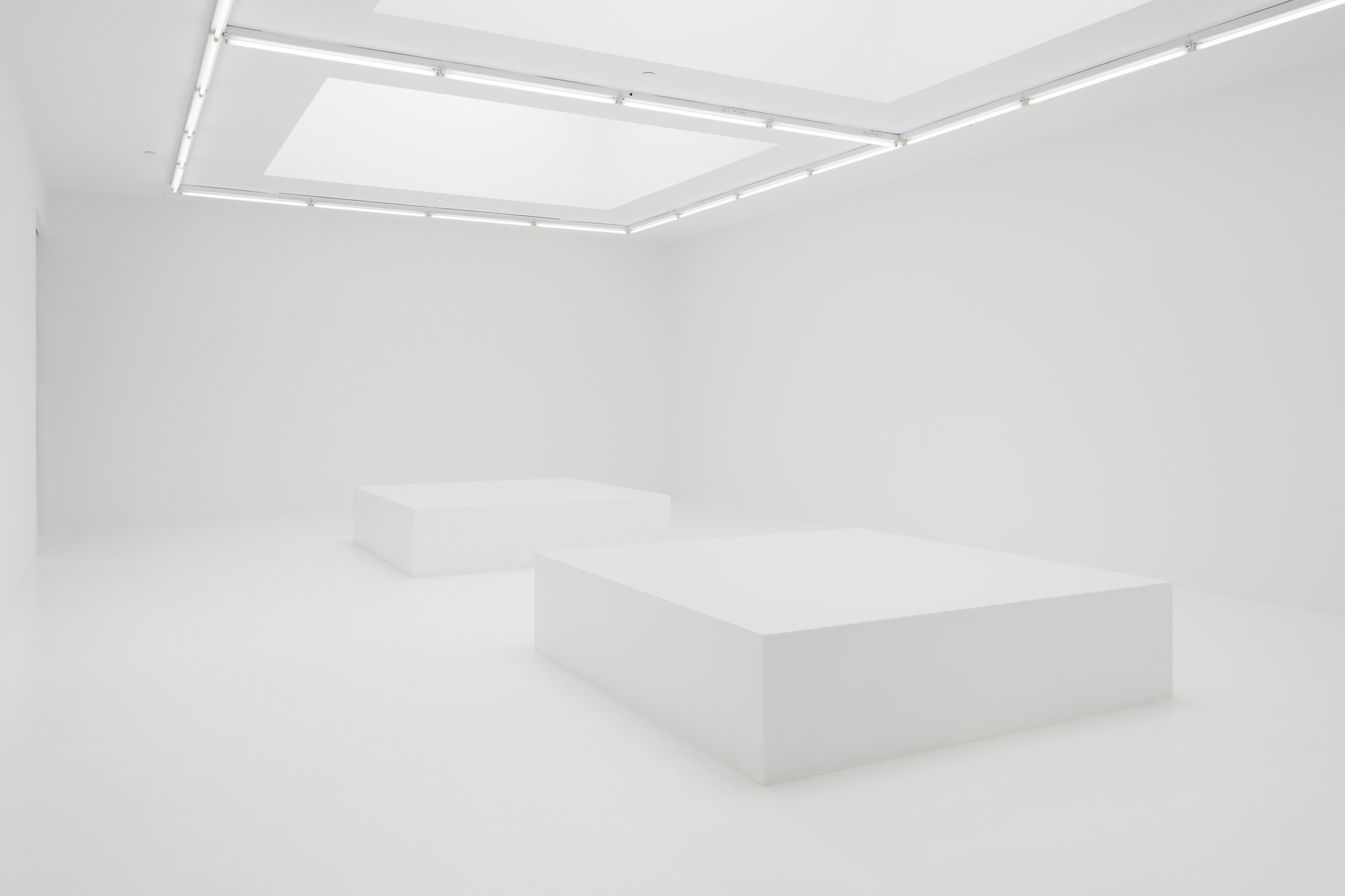

Agathe Pinard: Walking into the main room of the gallery, you are immersed into a white room with sterile light reminiscent of Kubrick’s last scene in 2001: A Space Odyssey while hidden speakers emanate sounds. I know you also hosted a couple of ‘Luminal’ sound baths. Where does your interest in making sound baths originate from ?

Jónsi: For the entirety of my career I have been interested in sound, sonic experiences and what it means. In every iteration of my artistic practice I have explored sound, what it feels like and what sensations it brings to the surface.

Pinard: With what idea in mind did you create the sound projected in the white room and the one in the dark room ?

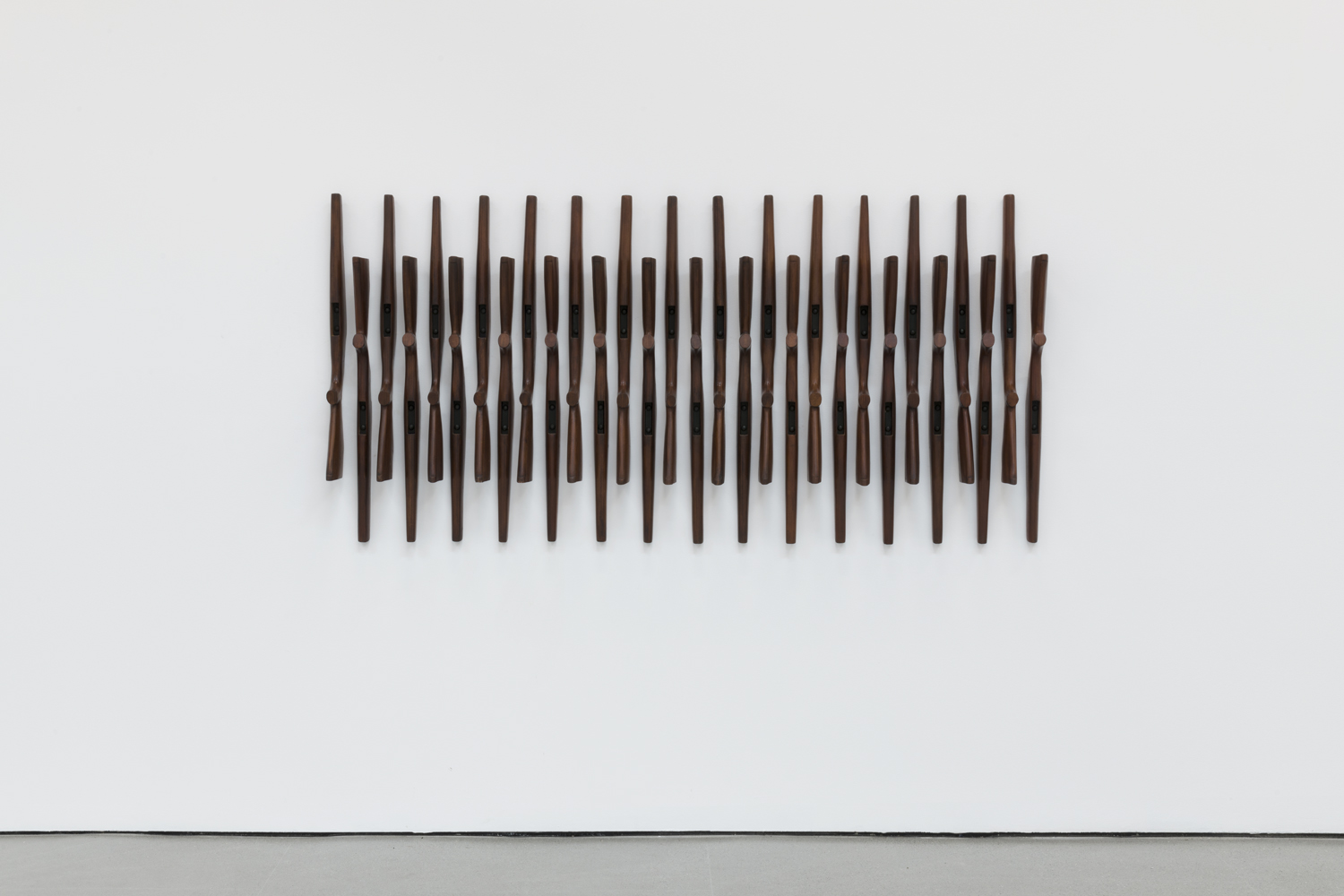

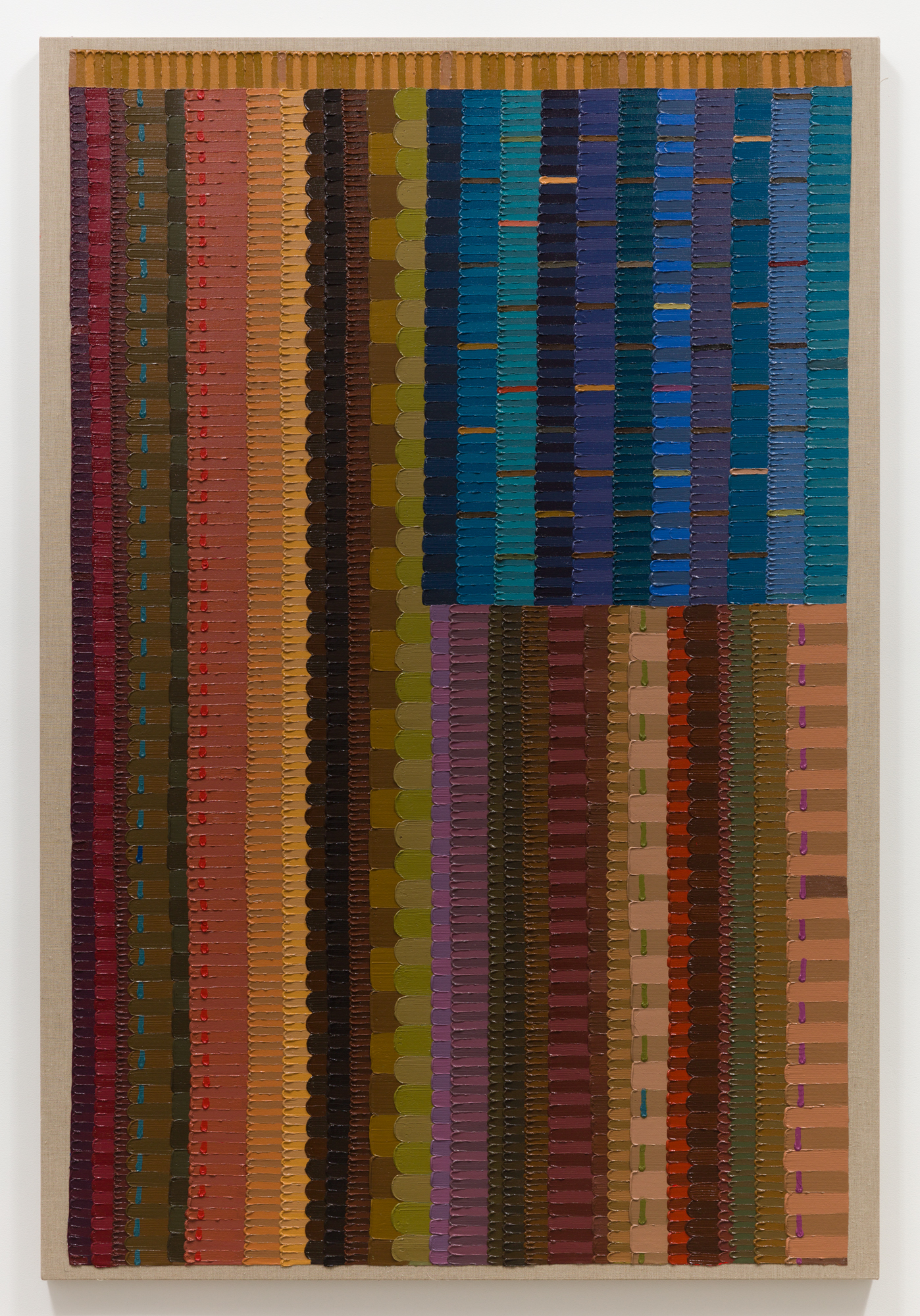

Jónsi: Each of these works has a different impetus, but they share so many common threads, which I believe run through the entire show and throughout my work in general. These are sound- based installations, but they activate the senses in more than one way-- using sound of course, but also sight, scent, and even the air moving through the room. Each of these works references the natural world on multiple levels, and functions as an abstract representation of our relation to nature. At the end, the sensorial is what inevitably connects us to the natural world.

Pinard: Could you describe the smell you decided to associate with each room and why?

Jónsi: In Hvítblinda (Whiteout) I was thinking about the idea of a whiteout as it occurs in nature-- a situation where the earth and the sky blend into each other to the point that the horizon disappears. The odor component in the room is ozone, which occurs in nature right before the rain begins. Svartalda (Dark wave) references the ocean: the ceiling panels move like a wave and part of the sound installation includes a recitation of an Icelandic poem about the sea. Here there is a seaweed scent which is an odorous reference to the sea.

Pinard: How does being submerged in a brightly lit white room as opposed to a dark pitched one affect a person?

Jónsi: Obviously each lighting situation affects the viewer differently. The sound component of each space enhances the experience of the space, together with the smell. But I think that in all the works in the show it there is an overall effect that goes beyond the visual.

Pinard: Your first solo show at Tanya Bonakdar Gallery is meant to be challenging to the senses – sight, sound, touch. It’s sort of a meditative, solo experience where the visitor is encouraged to focus on its senses while also sharing this experience with other people in the room. How do you want people to experience your work?

Jónsi: Sight, sound, smell are all intangible things that are part of the communal realm. While each of us experiences them individually, and maybe differently, these are things we cannot touch, or quantify, or have be entirely ours. The works in the show allow the viewer to have a very intimate and personal experience which is set in a public surrounding. It opens up ways to experience the distinctly personal together with other people.

Pinard: Your whole work of art is filled with vocal and instrumental approaches, from playing in your band Sigur Rós to creating movie scores to this show. How would you describe your own relationship to sound?

Jónsi: I think it is fascinating to work with something so intangible and invisible as sound but at the same time it moves you in some inexplicable and unexplainable way. Thats why sound is magical.

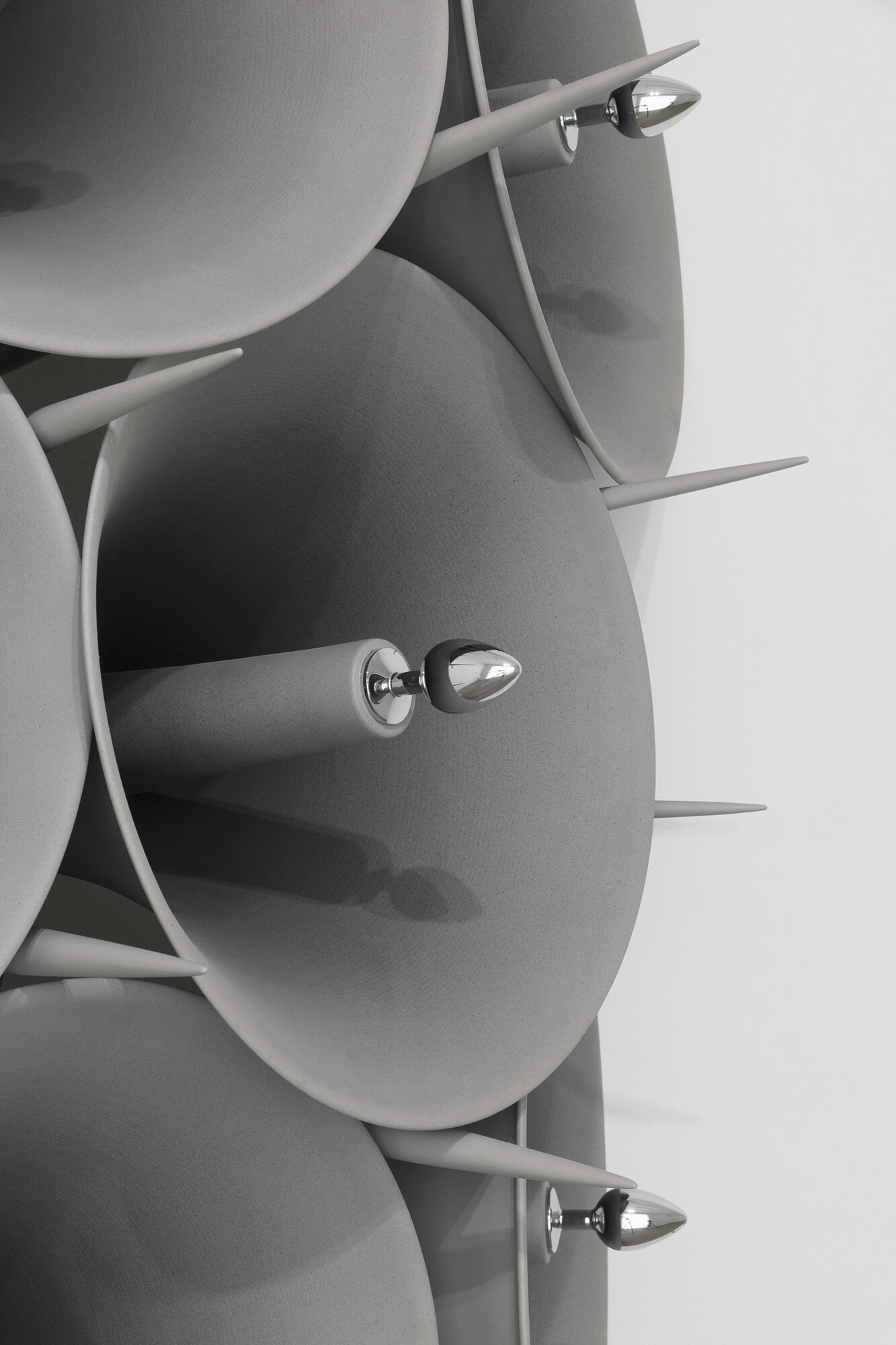

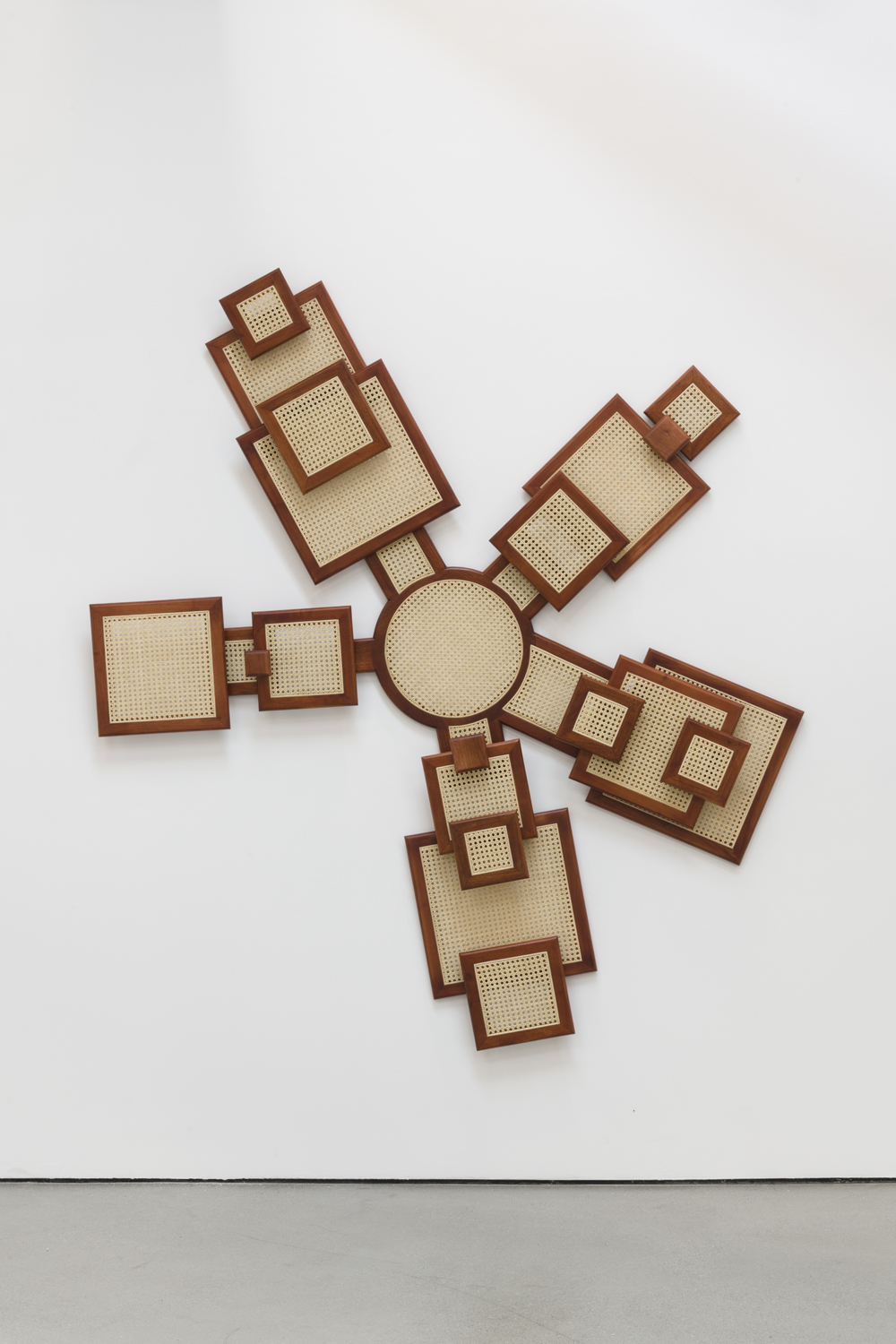

Pinard: Can you talk about the concept behind Í blóma ?

Jónsi: This work, like the others, is rooted in sound and in my ongoing exploration of it. The shape of the piece resembles the foxglove flower which is toxic but can also be used for healing and that’s a dichotomy I find interesting. Here there are field recordings of the actual flowers, and these recordings are layered with different recordings of my own voice. In the show there is a certain negotiation with the world we live in through sound, through nature, through the senses. It goes back and forth between the works and the viewer.

Pinard: Butt plugs are present in different sculptures in the show either made of glass or chrome-plated, why did you choose to incorporate this particular object into your work?

Jónsi: The human body is part of nature and throughout the show there are references to the body and to its physicality, in various degrees. The sexual body is a sensual organism, and bringing this idea forth is a large part of the exhibition.

Jónsi’s exhibition is on view through through January 9, 2020 at Tanya Bonakdar Gallery 1010 N Highland Ave, Los Angeles