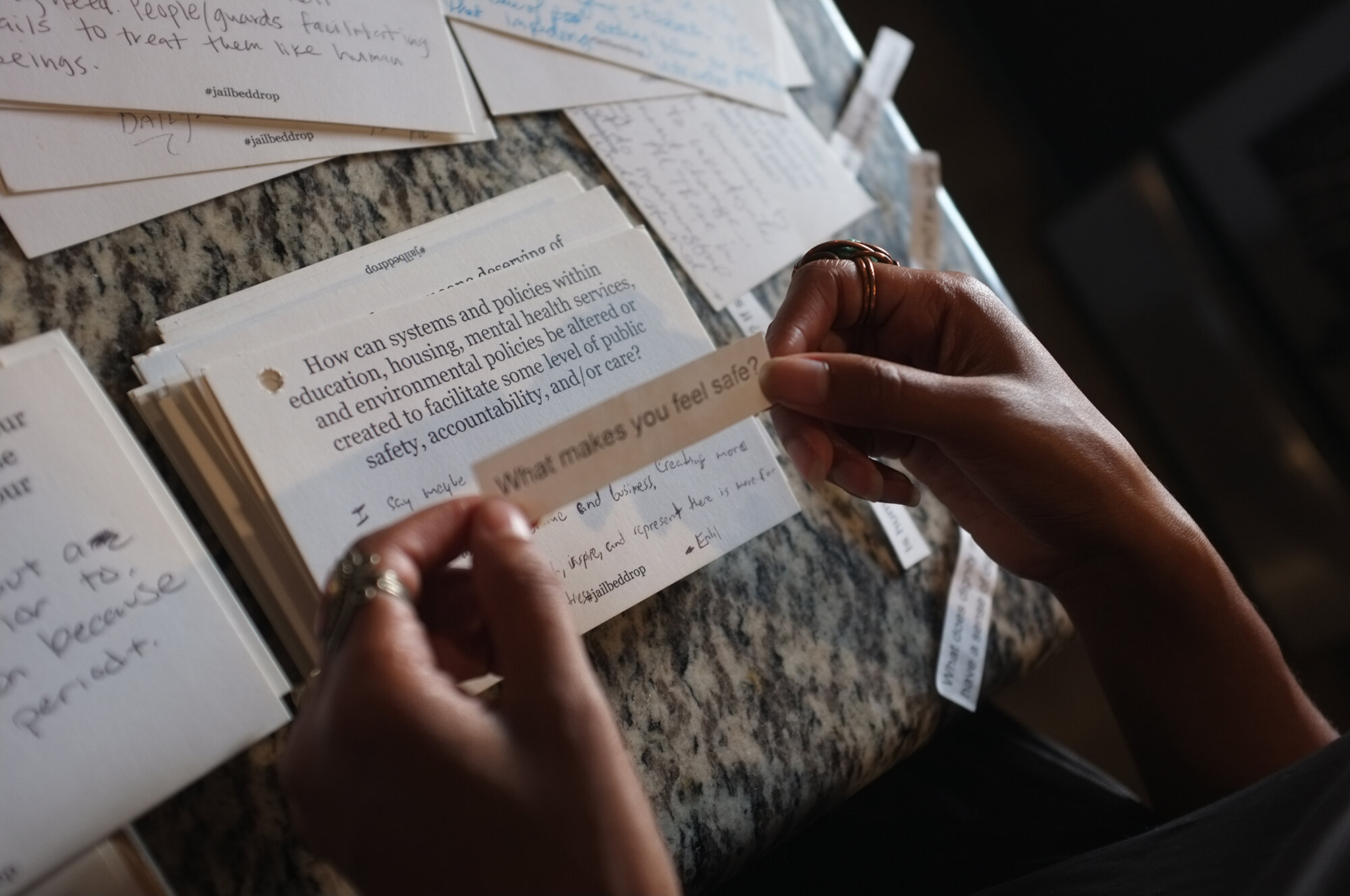

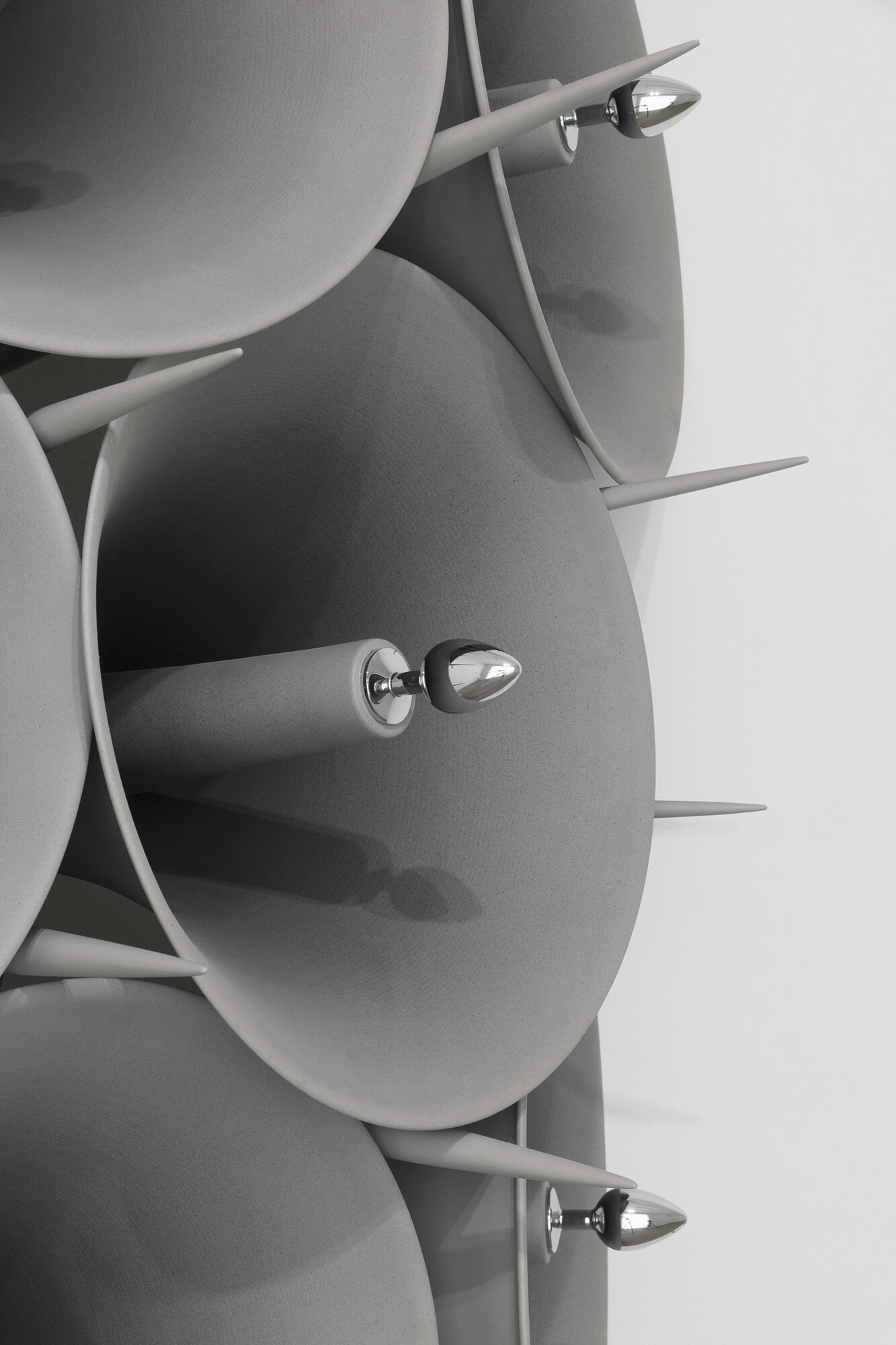

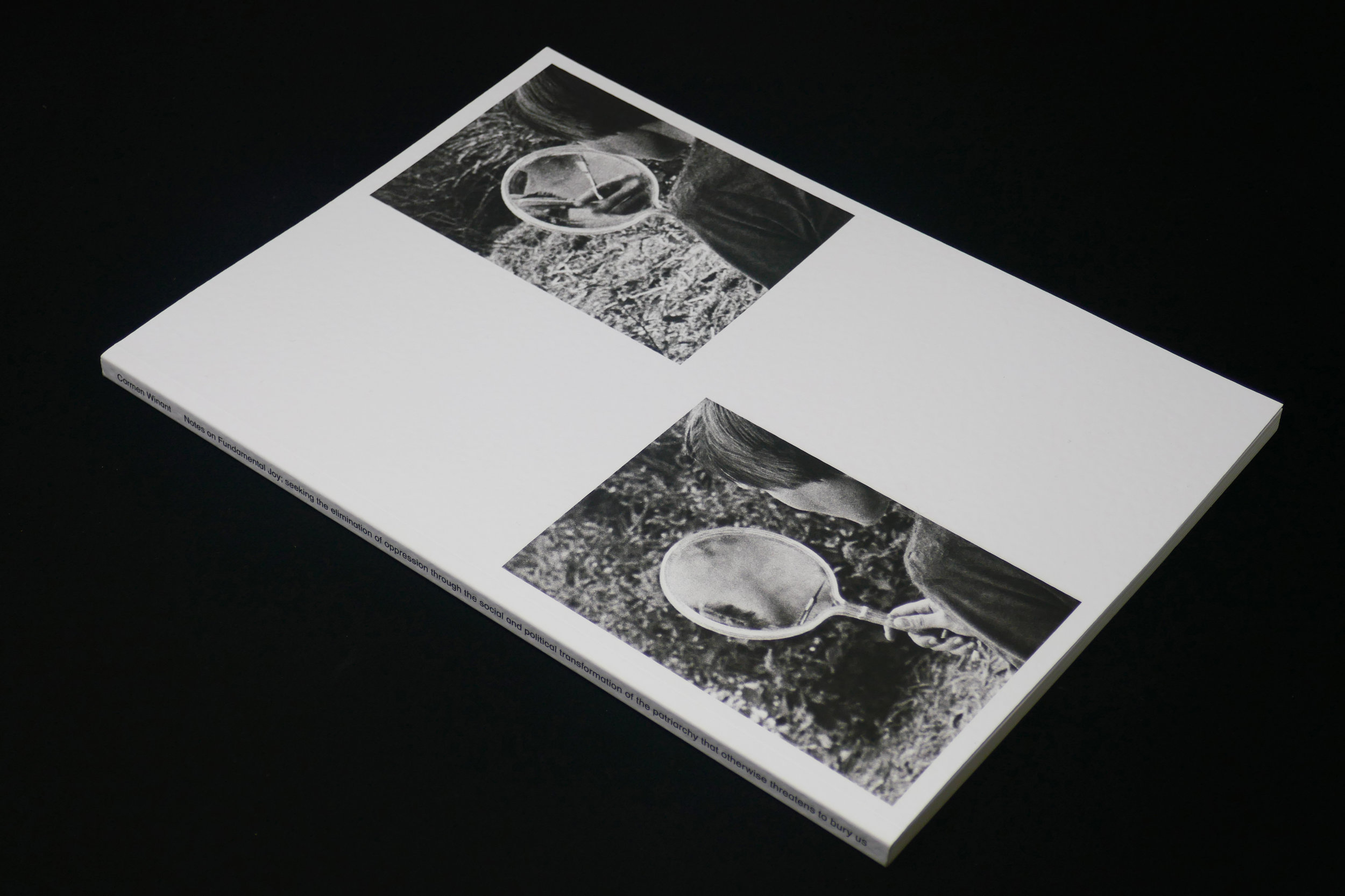

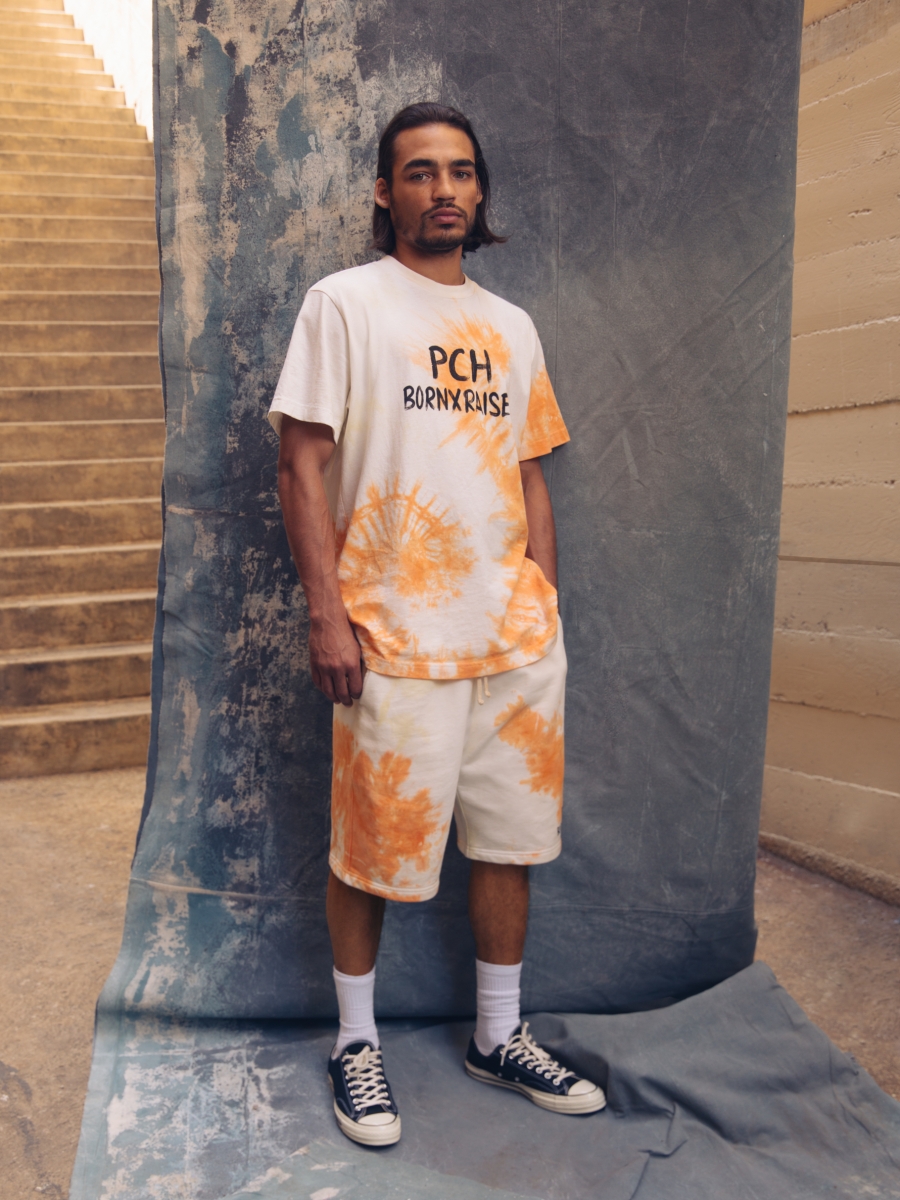

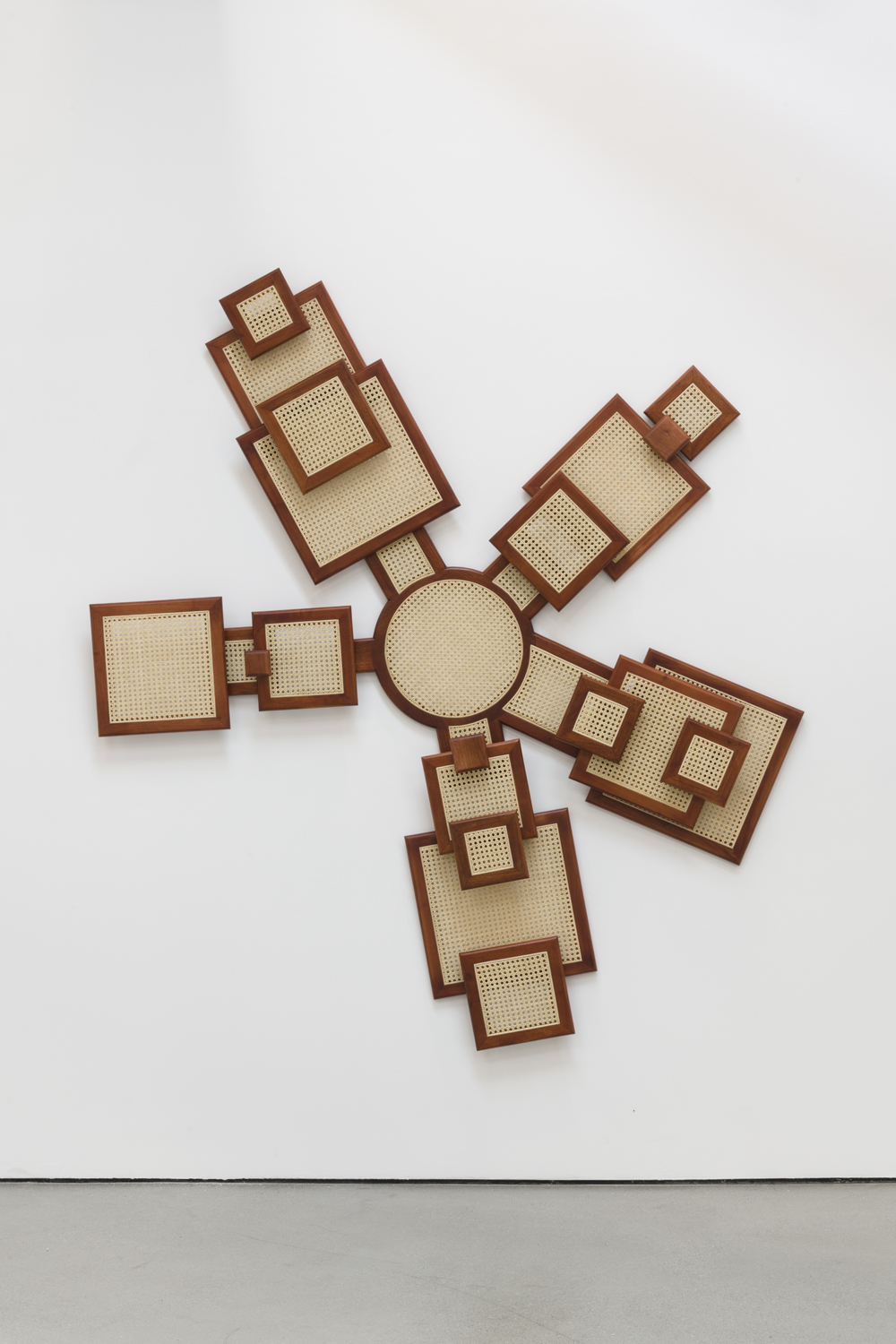

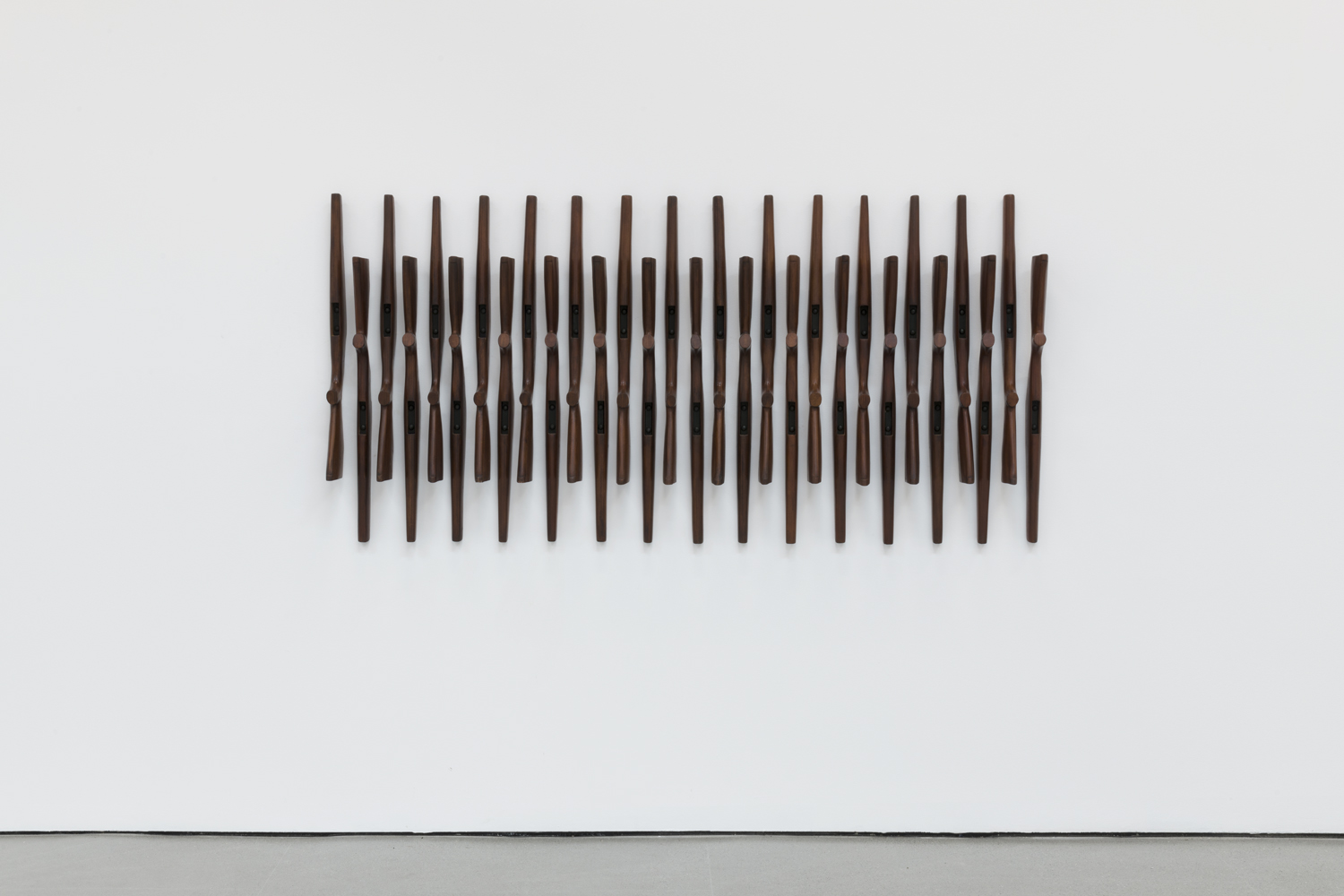

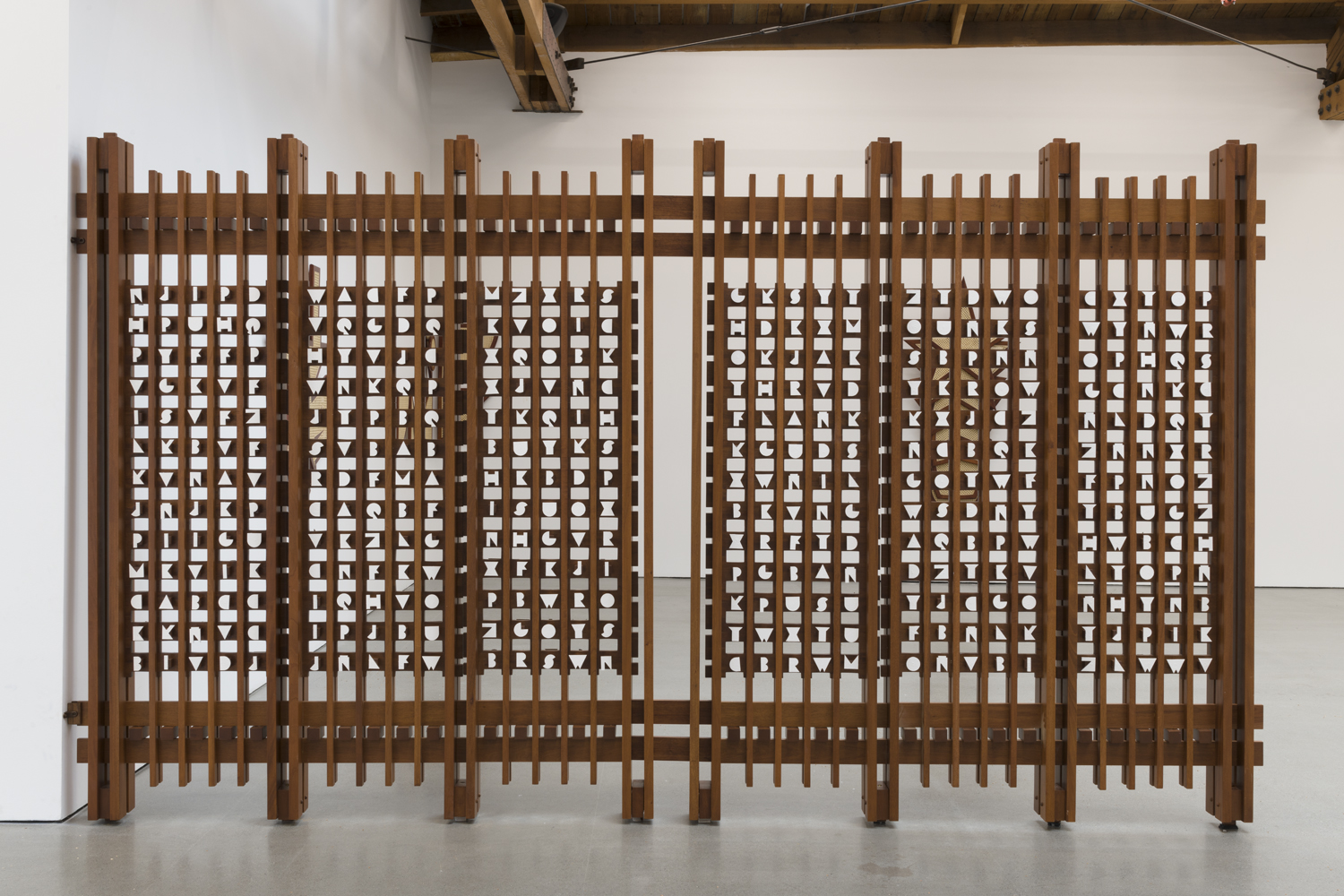

Mused SS 2021 Protect Your Mother, Love One Another upcycled collection

Two fashion insiders discuss the fashion industry’s pivot, and why fashion need not be considered frivolous, especially in ugly times.

Lindsay Jones is the founder, creative director, and head designer for MÚSED. The label’s latest collection, “Protect The Mother, Love One Another” 2021, featuring upcycled and gender fluid clothing is out now. As an activist Jones sits on the board of Equality New York and works with the Ackerman Institute’s The Gender Family Project.

Jill Di Donato is a fashion and beauty writer and professor who teaches communications and sociology at such schools as The Fashion Institute of Technology and Barnard College, where her class Is Fashion Frivolous? explores the political and social experiences of getting dressed.

JILL DI DONATO: Does it feel weird talking about fashion when the world is coming apart at the seams? There’s so much profound ugliness happening, how do you justify being concerned with things like clothes?

LINDSAY JONES: No! Fashion is a way of communicating with people. I’m reminded of les Incroyables during the French Revolution who were so punk rock and revolutionary, wearing eccentric clothing mixed with high-end jewelry from royalty who had been executed when they were redistributing the wealth. Clothing can be worn to bring people together during a revolutionary movement. It’s a soft power. Bring what you believe into all of the arts and design.

DI DONATO: I was working on a story that profiled photographer Dario Calmese who talked about fashion with a lowercase F as being “on the ground” as opposed to the fashion industry or the fashion system. When you think of fashion on the ground, it frees you up to see aesthetics as an immediate expression of identity. When fashion gets dismissed as frivolous, there’s often sexism, racism, or classism at the root, many times. Though of course in America, where much of the economy is based on racialized capitalism, and so much of fashion is based on cultural appropriation, there’s a tension that exists if you’re not discerning.

LINDSAY JONES: It can feel frivolous because not everyone understands the relevance of the period and how it shows symbols and values. People need to express themselves in these moments and use storytelling now more than ever. That tension you were talking about, it’s the old school magazines and model casting that’s not inclusive and tied up in aspirational luxury that’s out of touch. But there’s also the new vanguard.

DI DONATO : It’s helpful to remember that people make up institutions, which is where that kind of storytelling comes in. I’ve definitely uncovered some of my biases when it comes to storytelling, especially as a white journalist. Even though there are times at work when I don’t necessarily feel my power, like if I’m answering to an editor or department chair or bound by word count and can’t always print everything a source says. I’m not intentionally trying to silence voices, although from the source’s point of view, I can see how they might think that. I’ve been working on stepping outside of my point of view and trying to be as up front about what the process entails as possible. Also, admitting when I make mistakes. How are you navigating this terrain as a white designer?

LINDSAY JONES: During a summer of protests, we had to be quiet and we needed to listen. I'm still learning more about what I can do through listening and having humility and awareness about where my help is needed.

DI DONATO : The ability to listen is so powerful, and such an impactful skill. So much of my work as a journalist hinges on listening, almost more so than writing if that makes sense.

LINDSAY JONES: It does. And then given the pandemic, that’s sort of all we could do for a while. In New York we were forced to go inside and we didn’t know when we could come back out and that’s when I began to hand sew these pieces using recycled fabrics. It was personally cathartic and how I mentally got through that time.

DI DONATO : My creativity came in waves. There were moments when I felt an urgency to be part of these liminal spaces of the pandemic where everything had such charged meaning, and then there were times when I was overwrought with anger and sadness and hopelessness. Being a parent, though, it comes with a whole other set of challenges—it really prevented me from stewing in the voids of those days. Figuring a way forward was always on the forefront of my mind and I’m so grateful for that. When you think about activism in a time of crisis, it’s almost more essential that it happens and people find a way to connect.

LINDSAY JONES: In my experience, I’ve found that organized advocacy is highly effective. If you find a group you like and you like what they do, take classes and courses and trainings through them. They can help you volunteer and learn more about how to get involved. You will meet really impactful people.

DI DONATO : There’s so much good stuff going down on Zoom right now. Not to minimize these types of trainings and the type of commitment you’re talking about, and this is something different, but there were some days when having a training on while in quarantine kept up that forward momentum. More listening can never be a bad thing, right? Along those lines, do you feel like it’s okay to take joy in aesthetics right now?

LINDSAY JONES: Yes. In order for us to build motivation and energy self-care is essential. Wellness is an important part of activism. Enjoying art and film is important. We need time to receive in order to give more.

DI DONATO : You’re one of like five people I’ve seen in the past seven months. I remember the first time I walked to “town,” aka Abbot Kinney, when we met for smoothies and samples of Le Labo over the summer. It was a culture shock to me after so many weeks of isolation at the beach. I went home and cried afterwards. The feeling was a mixture of relief, I guess from the heaviness of everything, and being jolted into this life where treating myself was permissible.

LINDSAY JONES: People need to come together to take a break from the heaviness.

DI DONATO : The pandemic has completely shifted how I take care of myself, and in many ways, I feel like these shifts are for the better, stepping out of the frivolous stuff we were talking about earlier and into a deeper understanding of aesthetics and self-care. What are some things that are giving you joy?

LINDSAY JONES: Nature.

DI DONATO : Trails I used to take for granted have become sacred to me these days. I try to find some new flower or critter to wonder at. In that way, boredom drives creativity.

LINDSAY JONES: Yes! The mountains, and the ocean. Meditation. Baths. Tea. Special flower arrangements. I’m very into playlists. Playing music and practicing. Draping gowns [with Zac Posen in Central Park] and making art in nature, sculpting, cooking, gardening. Helping others gives me a sense of purpose. New Yorkers are happy to have a moment with each other right now. Most of the tourists are gone. People are sitting on the street again.

Click here to explore the collection.