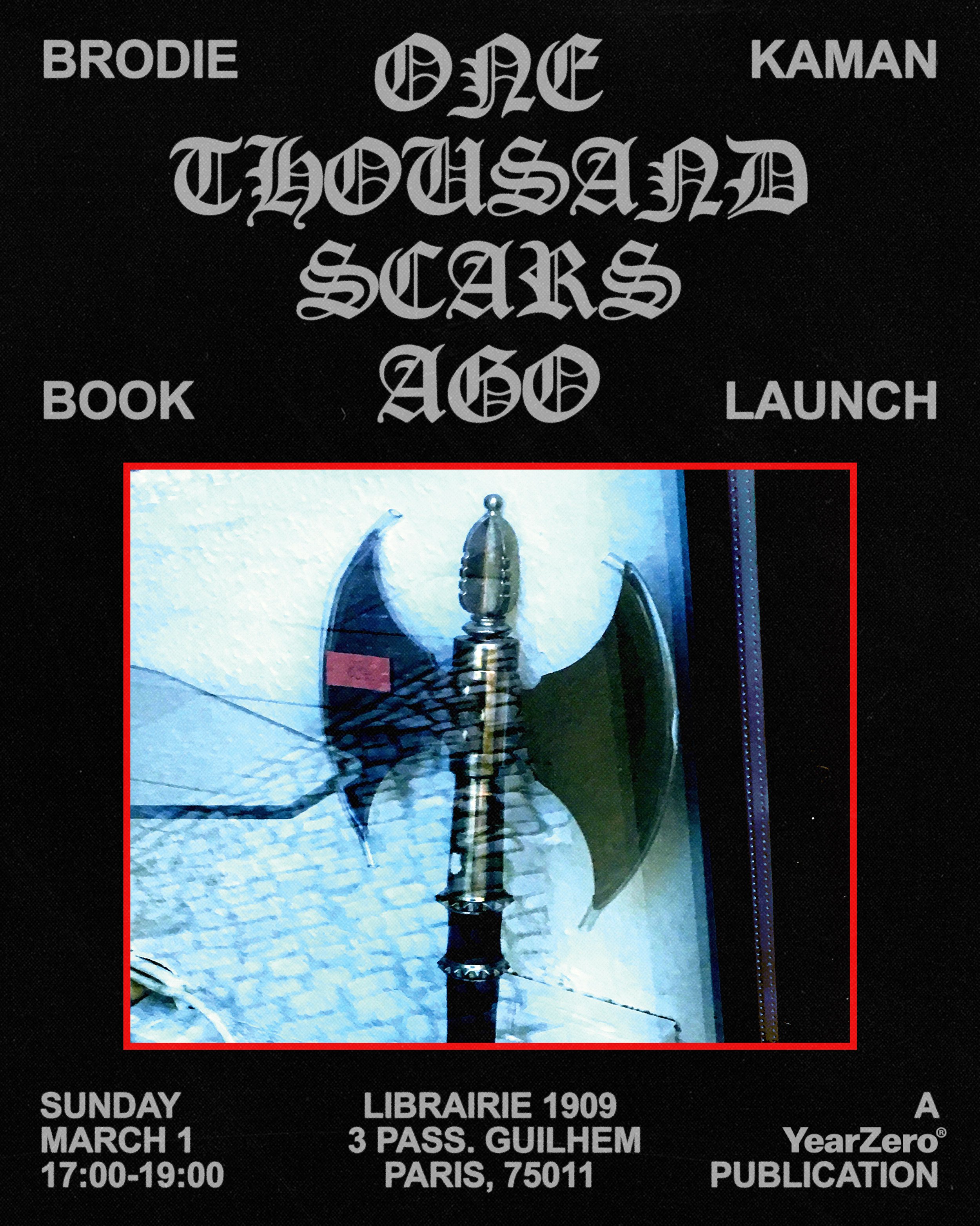

Amanda Ross-Ho at Frieze

text and images by Perry Shimon

‘Not Frieze’ LA exclaims, as in the international powerhouse art fair that provokes the broad ecosystem response we’re now calling Los Angeles Art Week. There are 8 fairs this year, of which I will see half, and an incalculable range of offerings calibrated to the influx of international art energies.

The main draw appears to be the lively and decorated Los Angeles crowds, which clearly preoccupy the guests more than the wall art. The fairs, with their high-key lighting, tiers of exclusivity, and long rambling promenades, are an easy win for LA audiences who turn out en masse for the spectacle and remind us—with a high calculus of automobile logistics—how poorly suited Los Angeles is to easy and spontaneous social gathering.

Frieze

Earlier this millennium, waves of displaced and precarious artists decamped from NYC and moved to Los Angeles in search of softer climates and more affordable, larger workspaces. There was a momentary feeling of discovery and excitement that quickly gave way to the predictable surge in real estate prices and attendant gentrification patterns. I wonder today where the center of cultural gravity exists in North America—less for market figures, and more for artist scenes and spaces—and it remains an open question for me. I let myself be carried away by the week, and then beyond, and sit here now with my phone open, doing a kind of mnemonic forensics to reconstitute a vaguely coherent narration of the unfolding events.

The Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel

Yunji Park

Carlye Packer Gallery

Felix, the bungalowed poolside alternative art fair extended across several floors of the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel, opened the proceedings and set an easy pace of socializing, art grazing, and scene clocking. Weaving in and out of modernist suites, I encountered notable presentations from Allesandro Teoldi with Marinaro Gallery and Erin Morris with EUROPA, beautiful and uncomplicated things producing pleasant feelings.

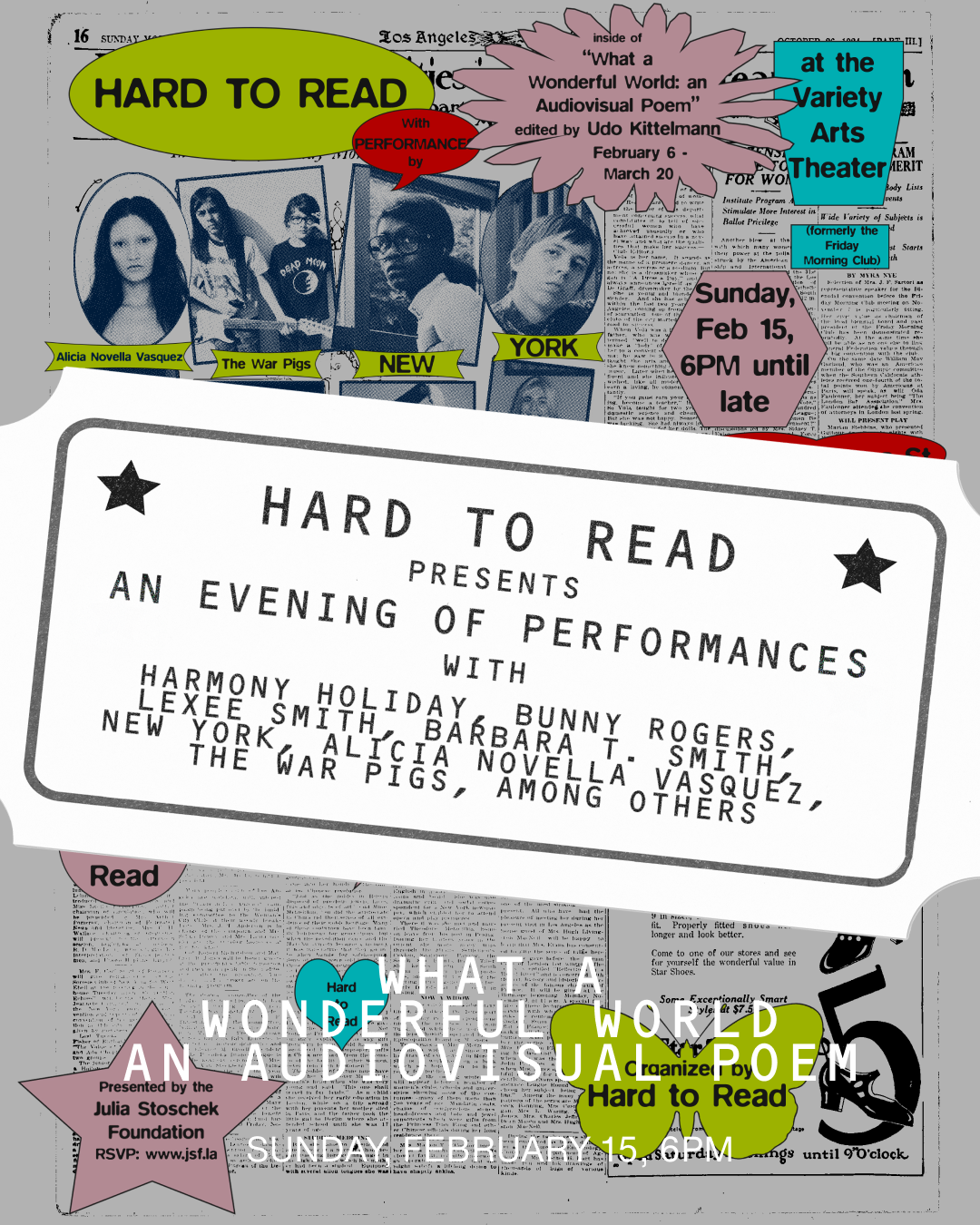

Julia Stoschek Collection at the Variety Arts Building

In the evening I went to what would be my first of three visits to the Julia Stoschek pop-up, who appeared to have fled the Berlin winter with a canonical collection of video art and installed what I heard billed as the largest such exhibition in US history, in the curious and dilapidated Variety Arts Building in the heart of downtown Los Angeles. The building has a fascinating history, initially constructed in the 1920s in a Renaissance Revival style to host the first women’s club in Los Angeles, with a grand auditorium for hosting performances and lectures, a library, galleries, and a banquet hall.

Buster Keaton

Cyprien Gaillard

Variety Arts Building

Anne Imhof

The knowledgeable docent at the entrance was offering historical overviews to the impromptu groups of guests gathered at the gratis popcorn counter. She informed us that after its life as a women’s club, the building became a vaudeville theater, underground punk club, rave spot, and then was bought by Justin Bieber’s megachurch, who brought it up to code and sold it during the pandemic. Fact-checking this oral history, I encountered the wonderful bigorangelandmarks.blogspot.com by local visual historian Floyd B. Bariscale, who documents historic buildings in LA, and encountered a lively comments section with contributions like:

Anonymous said...

MY NAME IS LONNIE HICKS. DURING THE YEAR 1980 I PROMOTED A VERY SUCCESSFUL DISCO IN THE BALLROOM ON THE FOURTH FLOOR ON THURSDAY NIGHTS ONLY. FOR TEN MONTHS I HOSTED PARTIES WITH SOME OF THE BIGGEST NAMES IN BLACK HOLLYWOOD .I TRIED VERY HARD TO ATTRACT A MIXED CROWD BUT IT NEVER SEEMED TO WORK OUT .SO WE WERE LABELED A BLACK CLUB. AT THAT TIME SEATING LEGAL ATTENDANCE IN THE ROOF GARDEN WAS 686 PEOPLE. MANY NIGHTS OUR ATTENDANCE EXCEEDED THAT FIGURE . THE ROOF GARDEN, IN MY OPINION IS ONE OF THE GREATEST BALLROOMS IN THE CITY. I FELL IN LOVE WITH IT FROM THE FIRST MOMENT I LAID EYES ON IT.I INTRODUCED MANY PEOPLE TO THE VENUE AND I USED ALMOST ALL THE BUILDING AT ONE TIME OR ANOTHER ; FROM THE THEATER, TO TIN PAN ALLEY, AND OF OFCOURSE " THE FABULOUS ROOF GARDEN". I WOULD LOVE ANOTHER SHOT AT PROMOTING THE ENTIRE BUILDING . I CAN BE REACHED FOR COMMENT OR INPUT ABOUT THE VARIETY ARTS CENTER AT 813-539-1965 OR AT TAMPASELESCT.COM

LONNIE HICKS said...

HI, LONNIE HICKS AGAIN. I FORGOT TO MENTION THAT JAZZ GREAT AL JARREAU RECORDED A SONG ABOUT THE ROOF GARDEN BALLROOM TITLED, OF COURSE, "THE ROOF GARDEN .IT WAS RELEASED ON THE WARNER BROS. LABEL IN 1980 .BECAUSE THE ROOF GARDEN WAS DESIGNED BACK IN THE TWENTIES TO BE A BALLROOM DURING THE TIME IT WAS AS A DISCO IT WAS TOTALLY THE CLASSIEST ONE IN TOWN; WITH A CAPACITY MOST CLUBS COULDN'T COME NEAR.BOY, THOSE WERE THE DAYS !!!

Our erudite popcorn docent was of the opinion this building should be converted into a long-term cultural center, and I agreed—keeping its rough-and-ready charm and availing itself to rotational curators doing seasonal evening programs of mixed-media art. And why not? How much tax money goes to subsidize sports arenas and Western imperialism instead?

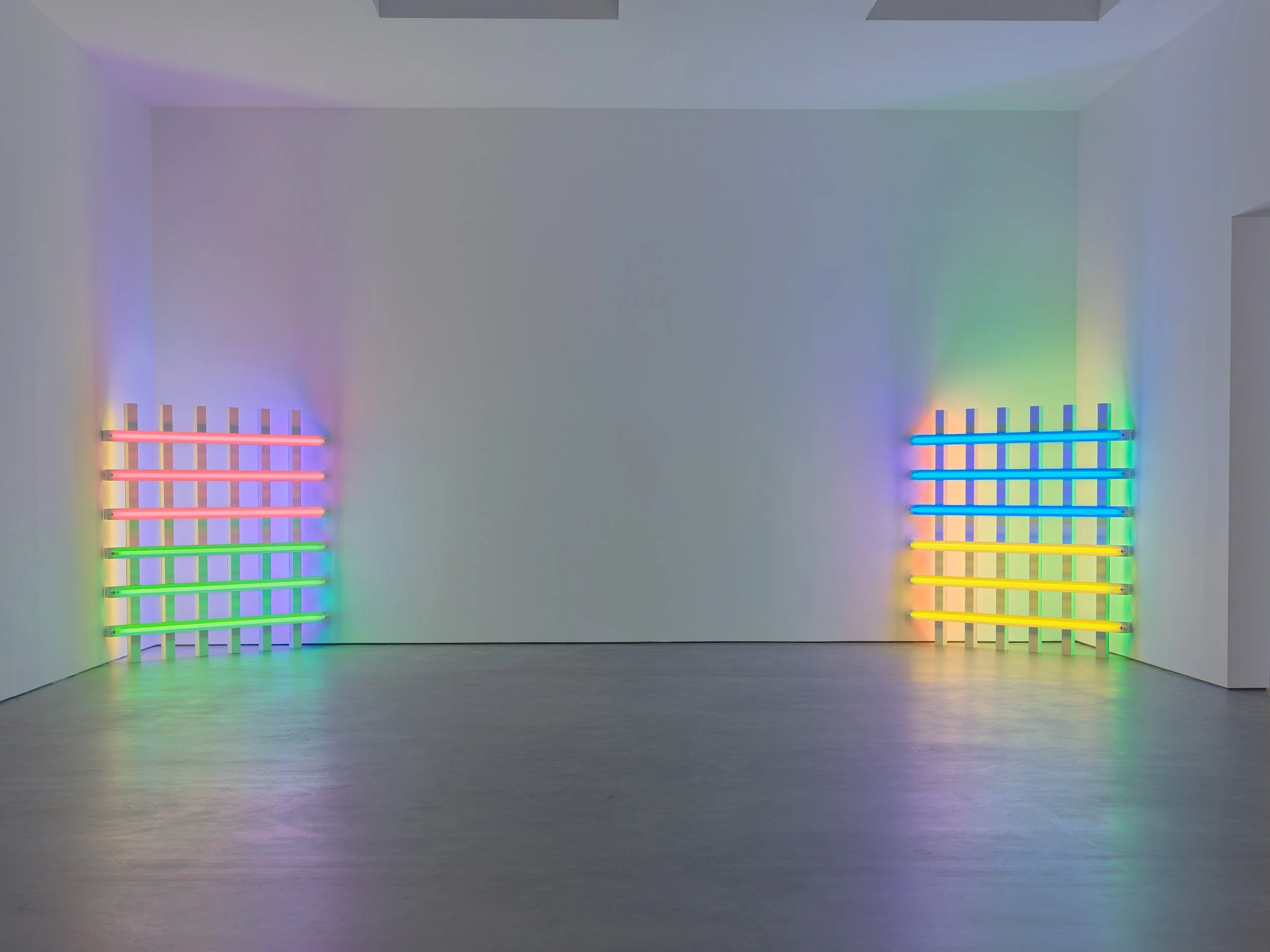

Stoschek's collection contours the curious canon of ‘video art’, an imperfect category of moving-image art put into crisis—or at least into history—with the rise of mass visual culture in the age of smartphones and social media. If video art emerges no less as a space of visual experimentation outside the formal codes of Hollywood and corporate media than as a way to designate certain works of moving image as scarce and rarified, it all seems to be awash in the disorienting deluge of moving-image production that overwhelms the present. I couldn’t help wondering how this arbitrary and idiosyncratic canon of video art would be remembered at the cusp of a visual revolution.

Arthur Jafa

Robert Boyd

The forty-some-odd works on view across five floors were hard to neatly characterize—though violence, sex, and power were distinct leitmotifs. Robert Boyd’s four-channel Xanadu displayed a frenetic MTV-era montage of political icons, fundamentalist movements, doomsday cults, and escalating war over a pop score in the basement of the building, with an orbiting disco ball. A kind of Christian apopalyptic millenarianism that would be encountered again in Bruce Conner’s preceding Three Screen Ray on view at the Marciano Collection, as well as in the infinite scroll of social media with its dizzying jump cuts of sex, violence, and pop music.

Bruce Conner at the Marciano

I encountered the sublime violence of Conner’s video works, monumentally installed and scored by Terry Riley, as a lilliputian war of American imperialism unfolded on my phone in streaming images, and I couldn’t wrest my eyes away—even driving down Sunset Blvd with its building-sized billboards advertising war films and luxury brands with deified and cosmetically sculpted celebrities. I began to feel as though art criticism has nothing to offer; nothing to elaborate on the unambiguous violence and horror of this country with its imperial realist aesthetic regime: coterminously streaming Al Jazeera and the US Dept. of War’s IG feeds as Tesla Cybertrucks surround me in front of Crypto.com Arena.

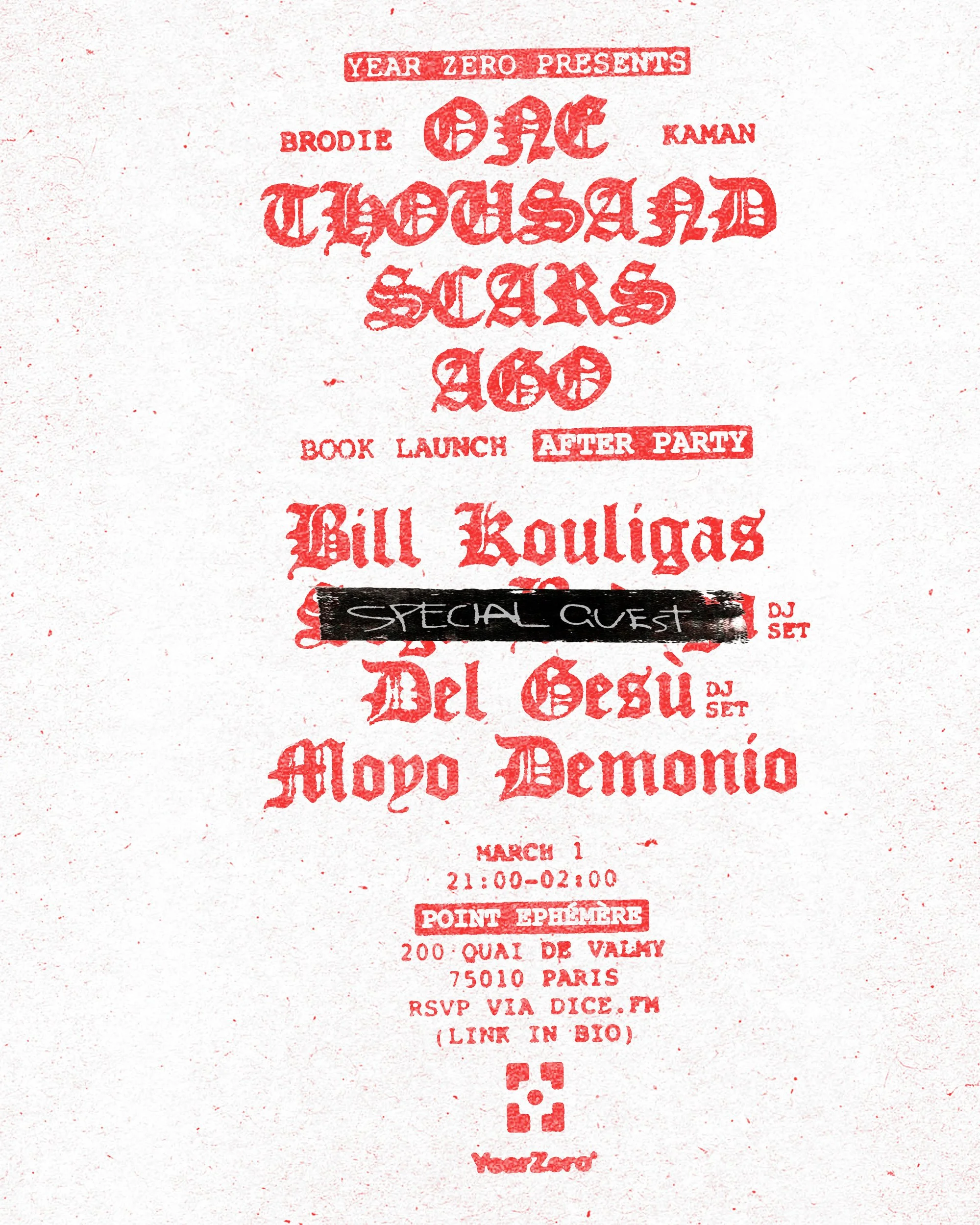

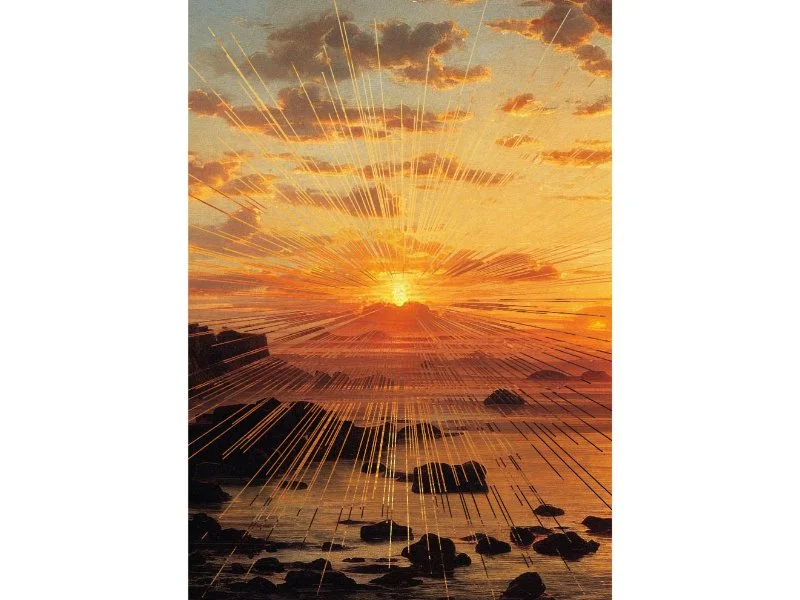

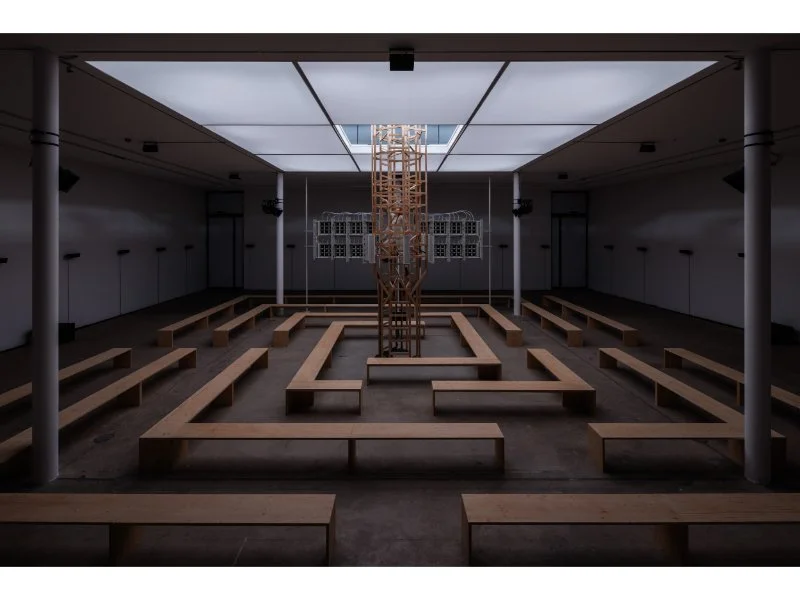

Outside of Frieze, on a manicured soccer pitch, a performance artist named Amanda Ross-Ho spent the duration of the fair rolling a giant inflatable earth, in an interpretive gesture I couldn’t help associating with planetary technocracy, geoengineering, and a global class of art elites for whom the world is theirs to play with recklessly like a children’s toy. Inside the fair was an incredible pageant of Los Angeles characters and a credible roster of collectible art.

At Marian Goodman, recently departed, Tacita Dean presented a collection of delicate chalk works, exquisitely beautiful and fragile drawings gathering chalk in gossamer gradations, collecting like weather and constellations, filigreed with fugitive fragments of poetry, salutations.

Nearby Wolfgang Tillmans shared his signature horizontalist, mood-board style of image-making neatly installed around the airy expanse of Regen Projects in Hollywood. A short looping video work in a back gallery, scored by Tillmans, circumnavigated a flowering wild carrot plant that seemed to contain the cosmos and announced the early Los Angeles spring: a teeming biodiversity region undeterred by automotive and anthropocentric impositions.

Wolfgang Tillmans

Wolfgang Tillmans

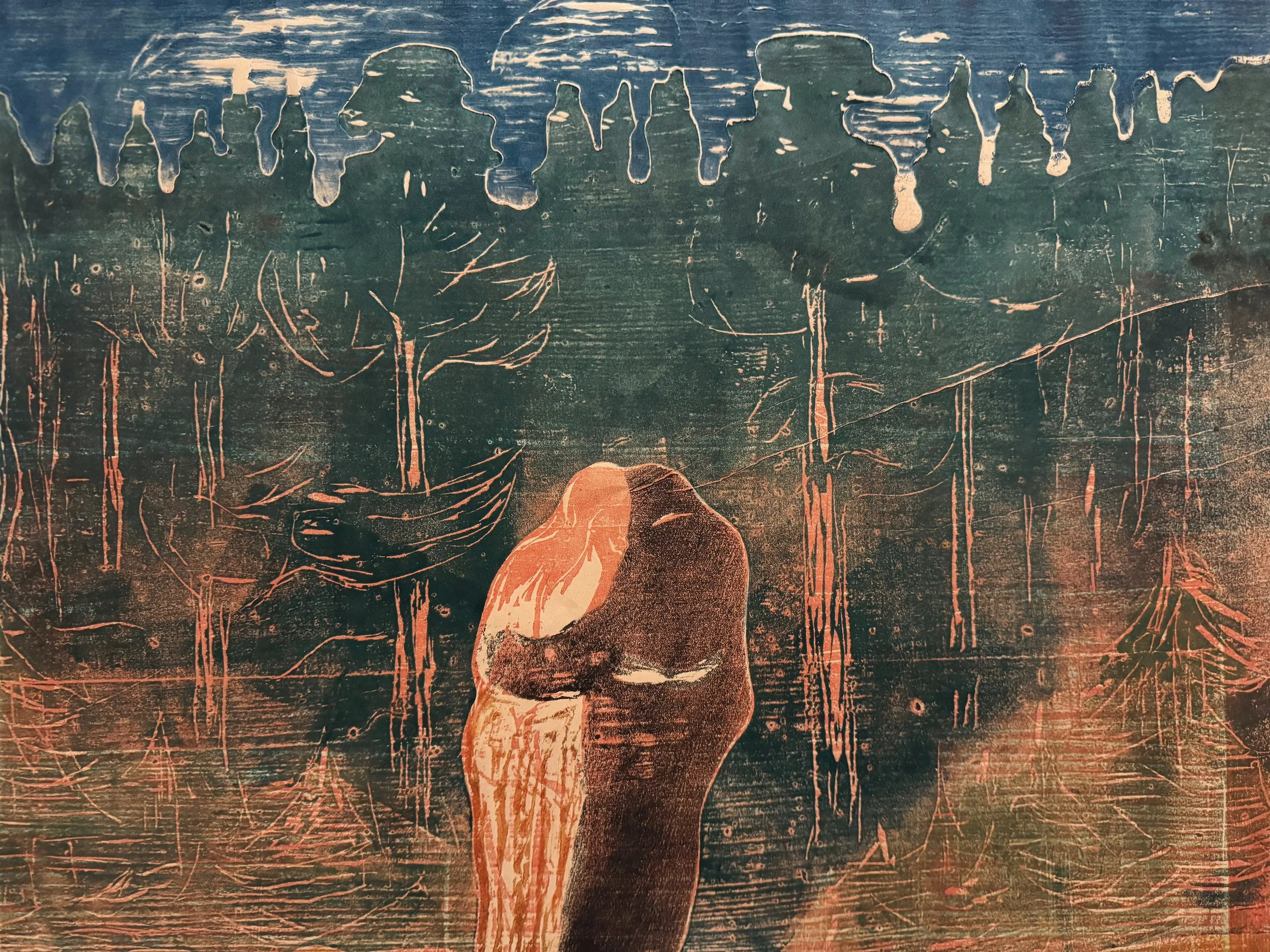

After all these small—and not-so-small—commercial offerings I ventured to LACMA to see some more historically rigorous and contextualized presentations. Walking past the open tar pits I came upon the sweeping modernist Geffen Galleries, still under construction, and traversing Wilshire with its grand curvilinear California modernist gestures. I spent some time with the Deep Cuts exhibition drawn from their impressive collection of block prints from around the world, and shows on Impressionism and Buddhist art, offering unexpected resonances and juxtapositions like a series of beatific Bodhisattvas perched in front of a symmetrical row of palms and Michael Heizer’s 340-ton granite megalith Levitated Mass.

Edvard Munch

Modigliani

Detail of Chakrasamvara and Vajravarahi 15th century Tibet

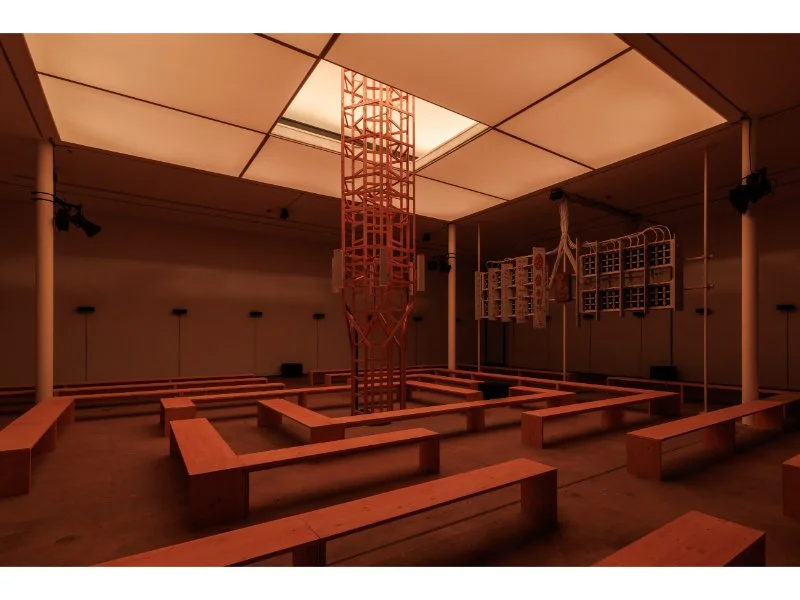

Kuwase Hasui

When making his 2000 debut Amores Perros, Alejandro G. Iñárritu left over a million feet of film on the cutting room floor. From this rejectamenta was assembled SUEÑO PERRO, a kinetic, smoke-filled cavern of multiple projections and cinematic machinery. The film assumes a quantum superposition as variations collapse in the ambulatory viewers, bathed and implicated in the recombining images. Its dually sculptural character: light extending materially through the haze and towering 35mm projectors like ouroboroi of flickering film, recursive and contingent.

A few blocks down along Wilshire were a trio of exhibitions housed in vacant properties owned by the same developer: a former Sizzler, an office building, and a 99¢ store—a kind of holy trinity of dystopian late-stage capitalism. The programming largely cleaved to each of the buildings' designated purposes. The Sizzler offered the kind of art popular in alternative art fairs: fast, unattractive, relatively inexpensive, and designed to produce simple palate-stimulating responses in its consumers. The office building offered a series of talks, panels, readings, PowerPoints, and other post-industrial forms of labor, slightly queered, Angelenosized, and performed in the drab and dispiriting cubicle and particle-board environs—picture attractive actors reading repulsive Paul McCarthy essays while guests sit uncomfortably in Great Recession-era office furniture. The 99¢ store offered a kind of anarchic, everyone’s-welcome free-for-all experience for maladapted objects and subjects, chaotic piles of capitalism’s overproduction and metabolic excretion.

I visited the Huntington for an early spring sakura and to see the beautiful tripartite Edmund de Waal exhibition 8 Directions of the Wind—after a line from a Bei Dao poem—rendering poetic stories of migration, diaspora, and exile with porcelain, poetry, marble, and burned oak. The installations and assembled libraries were interspersed across the flourishing springtime gardens and reflected quietly on quotidian ceramic practices inside the opulent architectures. Waal, descending from an aristocratic and oligarchical Jewish family persecuted by the Nazis, exhibiting the work in the sprawling pleasure grounds of a North American robber baron, produced an unusual setting for the reception of works informed by simple vernacular ceramic practices, or mingei; an uneasy migration between classes and cultural contexts that nonetheless rewarded close attention with the subtlety and poetry the works occasioned.

The impulse to escape into art as a palliative runs strong in horrifying times, and one finds little solace in the sun-soaked, hell-tinted, hypermediated LA art scene. Many conversations over the week centered on the elaborate social mechanisms of exclusion and affiliation that determine the social hierarchies governing the value of art in its institutional and financial inflections. These social rituals, in need of a dispassionate ethnography, eventuate in very idiosyncratic collections like the Stoschek and the all-night rituals of bacchanalian raves so popular with the same set. A student of both ancient Greece and the contemporary art world might notice the continuities between the mystery cults and the art world’s esoteric and largely inscrutable incantations, hedonistic dinners, and ecstatic late-night revelry.

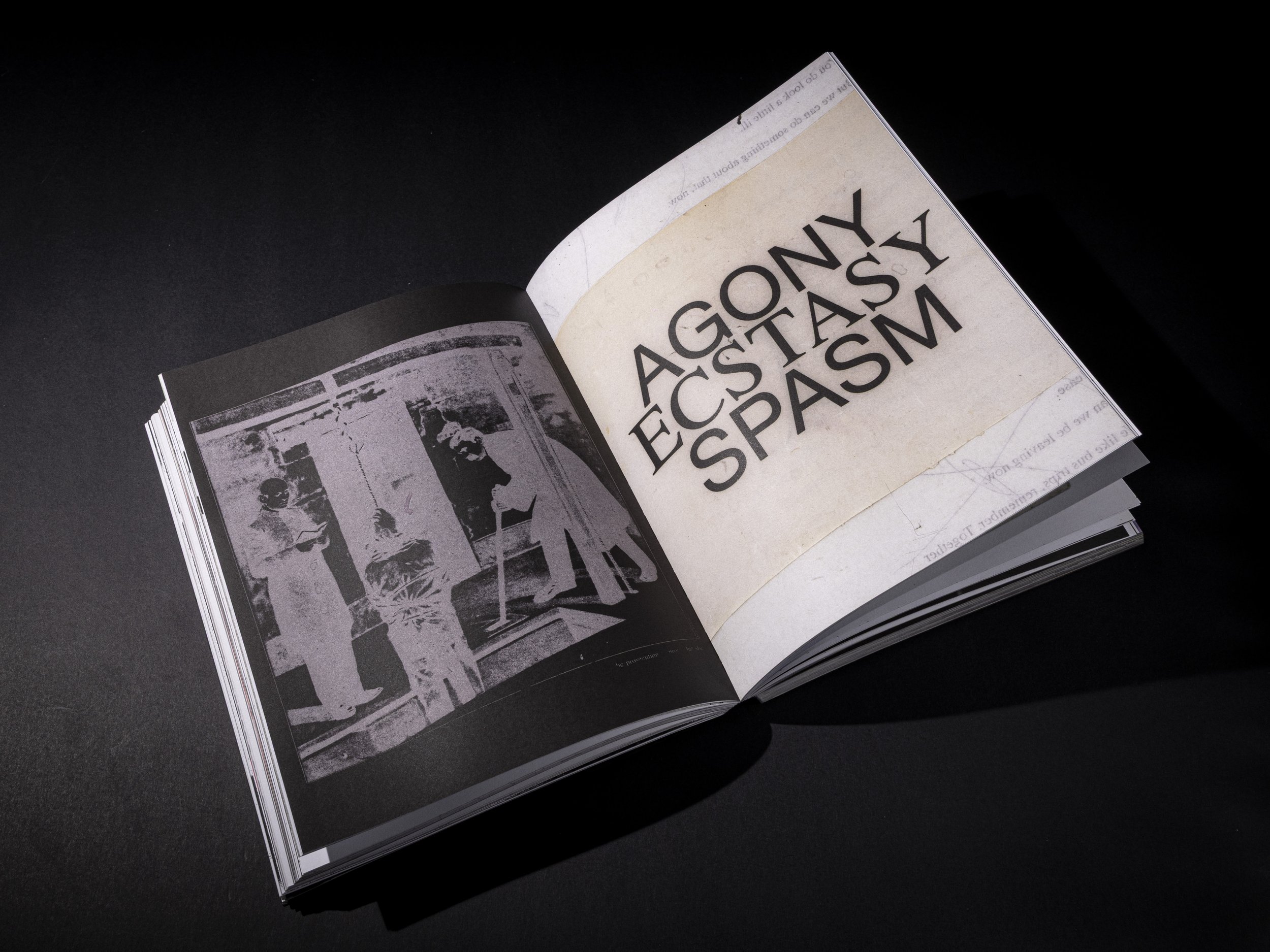

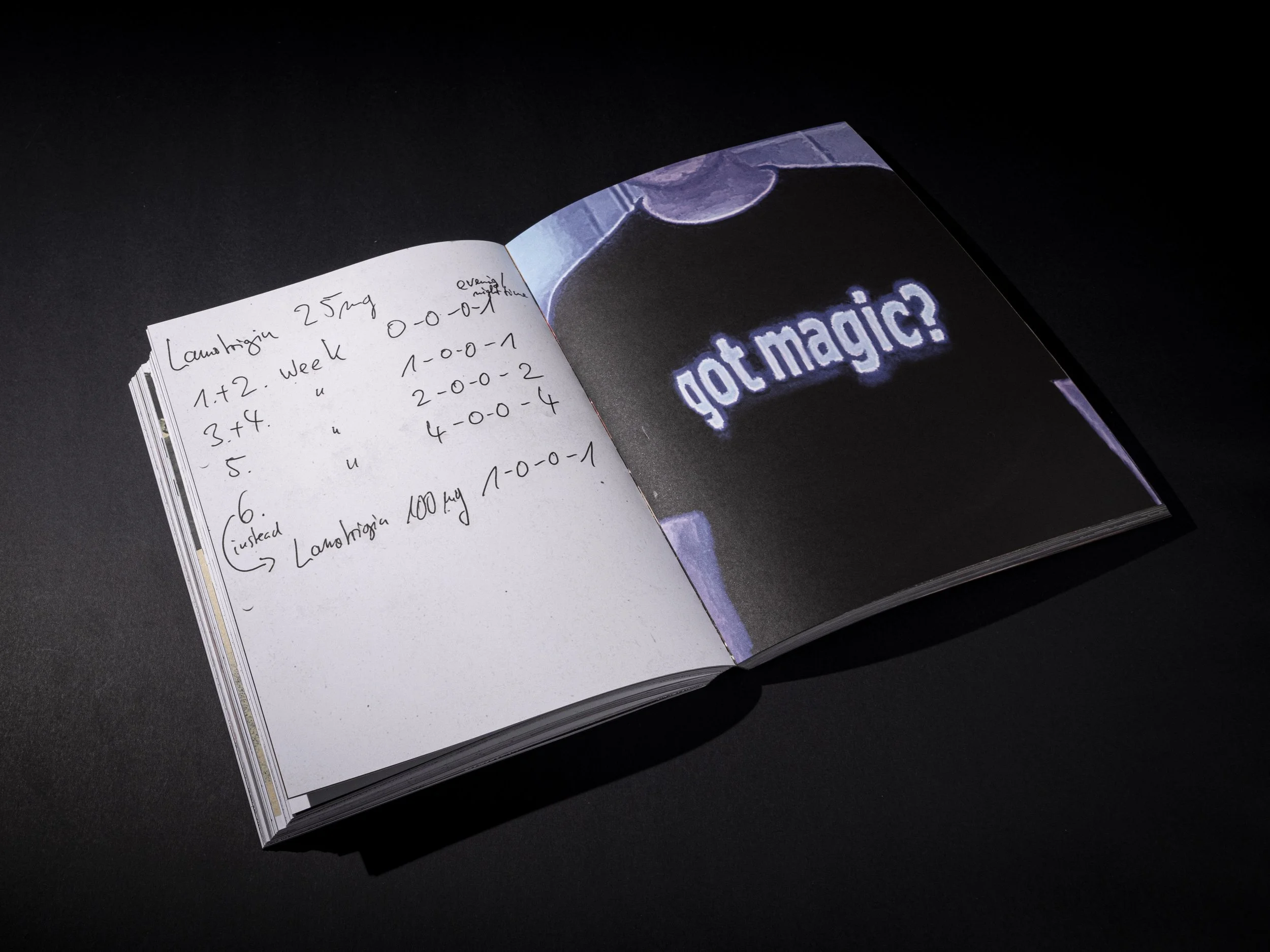

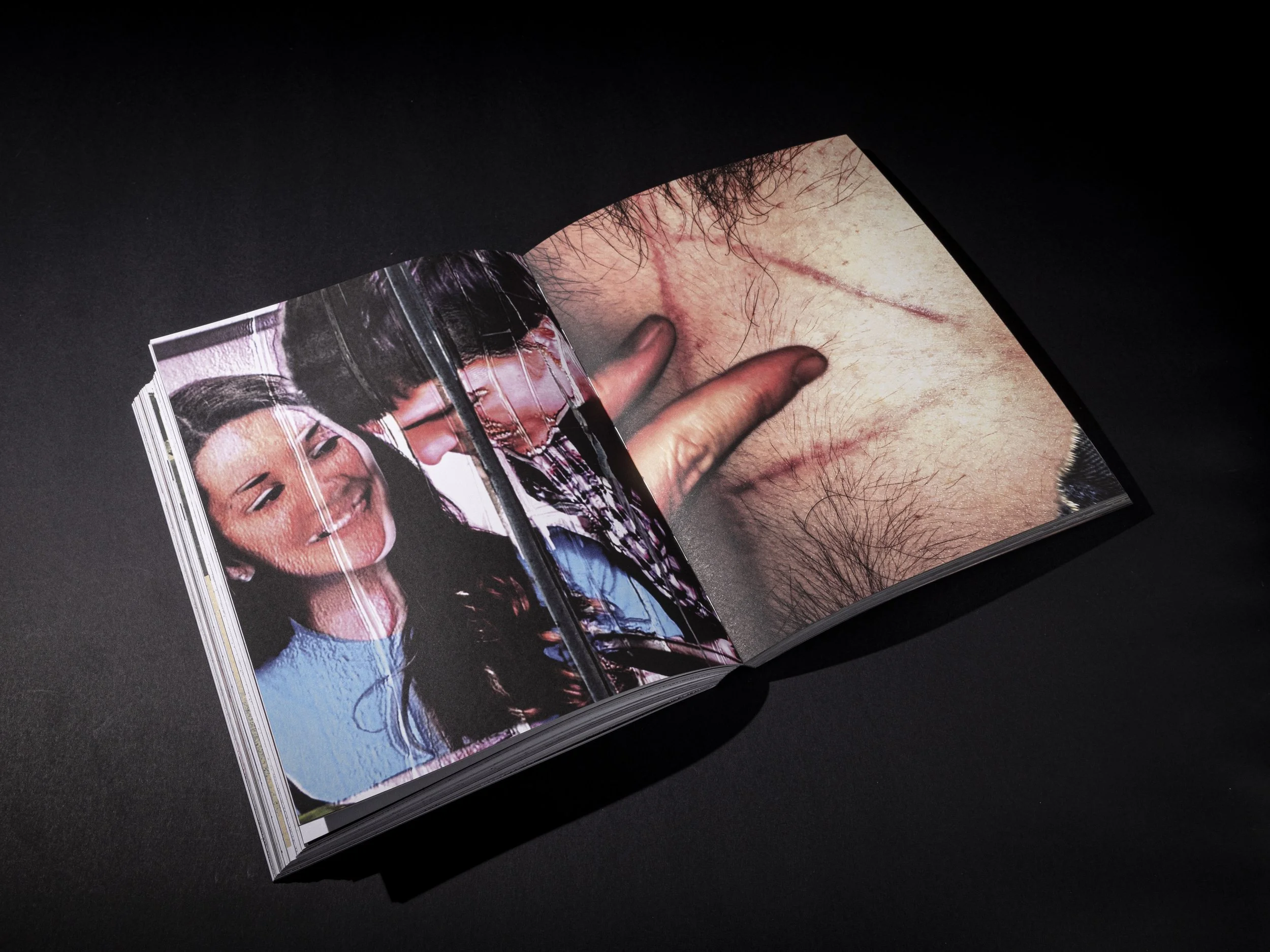

At the former Masonic temple housing the Marciano Art Collection, I attended a talk with the artist Una Szeemann, daughter of the late, storied Swiss super-curator Harald Szeemann, that centered on a collection of objects left with the estate when the Getty took his papers. Szeemann, a fascinating harbinger of an art world to come, was known for his indefatigable and idiosyncratic sprawling exhibitions anticipating our current vogue for superseding star curators and spectacularly scaled biennials. Una had curated a selection of minor objects, some taken from makeshift altars around her father’s southern Swiss Fabbrica Rosa estate, and presented them alongside thoughtful reflections from artists, curators, and anthropologists in a beautiful new library space generously featuring a browsable collection and modular furniture that rearranges to accommodate their public program. It had a kind of animist valence and invited speculation and meaning-making around these agential and talismanic objects.

Arriving at the Getty I encountered a descendant of Benjamin Franklin working at the gift shop and engaged in a rangey conversation about how the oil tycoon J. Paul Getty miserly installed pay phones in his home and about her practice of buying groceries for her colleagues’ undocumented relations who were afraid to leave the house on account of ICE raids. She was reading a book on the predominantly Black Sugar Hill neighborhood razed in the ’60s to install the I-10 freeway and went on to trace this kind of American racism back to George Washington, who, I learned from her, would rotate his slaves between Philadelphia and Virginia to avoid laws in the North granting them freedom after six consecutive months. I proceeded to a rather Manichaean-sounding special exhibition called Virtue and Vice: Allegory in European Drawing and found a suite of familiar and enduring ethical preoccupations. Describing the show later to a friend, I suggested they could have included a middle gallery—the size of the rest of the world.

Oh! If Only He Were Faithful to Me, Jean-Honoré Fragonard, 1770-75

Sitting in the Irwin Garden outside, I reflected on Jonathan Crary’s recently republished essay Robert Irwin and the Condition of Twilight, collected in the excellent Tricks of the Light, offering:

All of us within present-day technological culture inhabit a shifting mix of new and old perceptual modalities, of hybrid zones composed of Euclidean space and dimensionless experiences of electronic networks that often appear to be seamlessly connected. Thus even amid the fluctuating and unstable character of Irwin's work is a human subject who is still at least partially anchored within the enduring remnants of a Newtonian universe, even if these surviving components have been rendered contingent and spectral.

If the essay is astute in marking a shift into an increasingly indistinct virtual-experiential mode of seeing—if not being—and its attendant social parcellation, we are perhaps arriving at a time when these realms are no longer seen as dual and the visual takes on an agential role as it surveils and acts upon us, with increasing degrees of determinative automation.

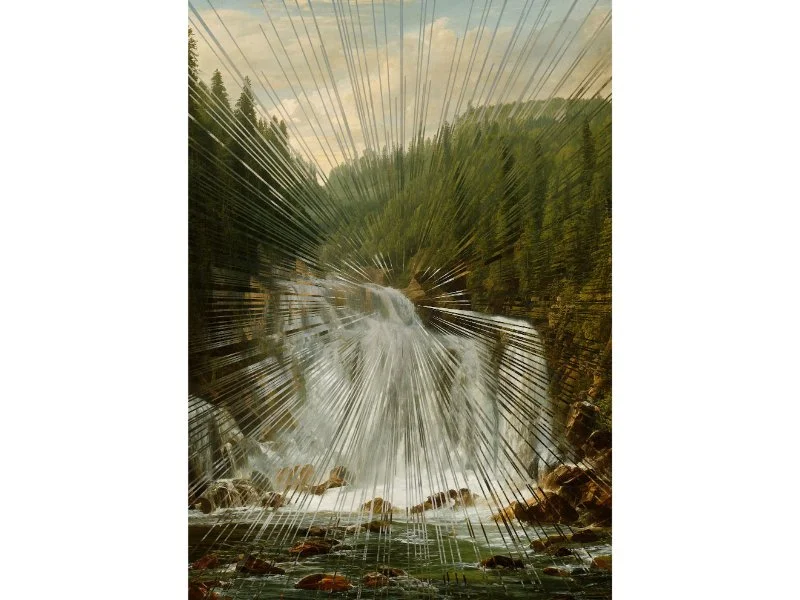

Blinn and Lambert

At a new gallery in Chinatown, North Loop West, I saw a beautiful exhibition, another instance in a burgeoning—or perhaps continuing—Light and Space revival, from an artist collective Blinn and Lambert who darkened the gallery with large canvases covering the windows, with shapely apertures filtering warm light into the welcome cool calm of the gallery with the shifting sun. 35mm projectors set at 8:20-second (the time it takes light to reach Earth from the sun) and 60-minute intervals respectively threw cameraless pictures of light onto the walls creating a restorative and contemplative respite from the blazing sun and art-world velocities outside.

Meara O’Reilly and vocal ensemble

Solarc

Gathering a gift at the excellent Skylight Books, I chanced on a painful conversation between Maggie Nelson and Darcey Steinke about their respective surgery memoirs. I joined a new friend at the well-programmed 2220 Arts + Archives space for an evening of hocketing, or a staccato call-and-response vocal musical style popular in medieval Europe, central African vocal traditions, as well as corners of contemporary pop music, with LA composer Meara O’Reilly and her distinctly (and adorably) East Los Angeles-feeling vocal ensemble. The music felt fitting for an age of binary computational logic and stuttered along charismatically toward a higher-resolution but distinctly atomized kind of being-together somehow commensurate with our times. The following night we reconvened for the First Friday Flute Club gathering at the artisanal brewing new-music venue Solarc in Eagle Rock and enjoyed the company of a diverse cross-section of enthusiastic flutists sharing instruments, melodies, and fermented drinks.

Driving back to the Bay Area, the center of gravity for these new global technocratic shifts, I climbed the windswept arid pass, bracing my tiny 20th-century convertible against the Santa Anas, pushing it through the endless variable monocultures: grapes, cotton, citrus, almonds, houses. The absolute horror and putrefaction of the cow slaughter fields. A domestic dog split open on the side of the highway from a high-velocity impact with one of the innumerable trucks dwarfing me with their containers of terrible decisions and menacing spinning wheel-spikes.